FAQ

Below is the list of some of the things I find myself explaining on a regular basis. I get a lot of messages from students, artists looking for advice and folks who just want an old-fashioned brain-picking session. As I’m now drowning in email on any given day, I tend to view my inbox with the eye of a triage nurse. So please don’t be offended if you don’t hear back from me, and take a gander to see if you can find an answer to your question here:

What is Anagram Press?

In addition to illustrating for commercial clients and publications, I create my personal work under the umbrella(s) of a variety of side projects, like Drawn the Road Again, my illustrated travel blog, and the Dead Feminists, a two-woman collaborative poster series. Anagram Press is the name of my in-house brand of products like stationery and gift items, hand-printed artist books and broadsides, and fine-art originals and prints. I started Anagram Press in 2004, and now have a stable of several hundred products and many retailers across the U.S.

The name Anagram Press comes from the process of typesetting, since I have a background in letterpress printing. The physical act of setting movable metal or wood type by hand involves moving individual letters around—just like you would when solving an anagram puzzle. As a letterer, I create my own type; and since creating any image is a type of creative problem-solving, “Anagram” really resonated with me. The “Press” part of the name is a nod to the early letterpress printers and the continuing customs of the book arts world. Artists who print or publish their own writing and imagery traditionally do so under the moniker of a press name—I got my start as an artist in that world, so the name reflects that.

Also, the art of anagrams was originally known by the Latin term “ars magna” (“the great art”)—which is an anagram of “anagrams.” I love stuff like that.

Oh, and my favorite anagram of my name is “Coralled Hyena.” I hope this phrase is not actually reflective of my personality.

Ahem. Anyway.

Do you take commissions?

I am available for editorial commissions, commercial work and licensing; if that’s something you’re looking for, please give me a shout. On seldom occasions I will take private commissions for various organizations and small businesses, but balancing my ongoing commercial projects with my personal work means that I’m almost always booked. It’s very rare that I can accept a project with a last-minute timeline, and as my entire business consists of just little ol’ me, I have to turn down even the most tempting opportunities, all the time. I hope you’ll understand if I can’t take on your project.

How can I purchase your work? Can I buy your stuff at a shop in my town?

You can find cards, artwork, and other goodies in my online shop!

Or if you’re interested in the Dead Feminists series, you can find prints and postcards in their very own shop.

My travel blog, Drawn the Road Again, also has its own shop, full of travel-related artwork and sketchbook prints.

Or if you’re not sure where to start, or you have something unusual in mind, you can just contact me directly.

If you prefer to shop in person, here is a list of retailers that carry my work. Be advised, though: I don’t have any control over inventory, staffing or restocking at outside retailers, so if they sell out of my stuff or change reps, I won’t always hear about it. If you’d like to see my work at your favorite retailer, it’s always good to contact them directly and ask!

I’m a stockist. What do you offer for wholesale? Can I order online?

I have a veritable boatload of cards and digital prints available! For wholesale orders, I am represented by Artemis Book Sales in Portland, OR. You can find ordering details and download a copy of my latest wholesale catalog (including prices and terms) on my wholesale page. You can place a wholesale order for your shop by contacting Artemis Book Sales.

I’m hosting a craft fair/art festival. Will you be a vendor at my event?

I am always interested in events with indoor vending opportunities, though my limited schedule means that I have to be choosy. If my work is a good fit for your event and I can make the timing work, I enthusiastically apply for (and say yes to invitations to) many live events throughout the year. I look forward to hearing about your indoor craft fair or art festival, and I hope we can be a good match for one another.

I don’t do outdoor events, however. (The only exception is for outdoor events that also have some sort of indoor area, like a farmers market with a permanent covered pavilion.) I am not equipped with the infrastructure for outdoor shows, my paper goods are too delicate to risk displaying in inclement weather (heat, wind, rain, etc.), and I frequently travel during the summer when most outdoor fairs are held. I only have the time and resources to do a limited number of live events each year, and the simplest place for me to draw the line is at indoor vs. outdoor. So I’m very sorry—no matter how wonderful or well-attended your outdoor arts fair or street festival is, I will have to turn down your invitation. I hope you’ll understand.

Can I use your illustration for my website/blog/tattoo/event poster?

The images I post online are not licensed for personal or commercial use. All of my work is protected by U.S. copyright laws, so please do not use my images or writing without my written permission. Purchasing artwork does not grant reproduction rights or transfer copyright.

If you’re interested in licensing one of my images for your product/project/event/tattoo/etc., please feel free to contact me.

If you would like to do a feature about my work in your publication or blog, thank you! Please credit me, and let me know so I can help spread the word for you!

Will Anagram Press publish my book? Print my wedding invitations? Emboss my name on one of your prints?

I’m afraid I’m not available for letterpress or other printing commissions.

I have an idea for a children’s book/magazine article/self-publishing project. Will you illustrate it for me?

The short answer is no, but since I receive this question possibly more than any other, it deserves a more detailed explanation.

Another exception is if the writer is self-publishing. If you are looking to self-publish and would like to hire an illustrator for the project (and please do hire them, rather than asking them to do unethical spec work!), the easiest route would be to reach out to your local artist community. Is there a local listserv or Facebook group where people post opportunities for artists? If so, you can easily pitch your project and budget there, and interested artists can contact you.

Do you teach classes?

Only once in a blue moon do I teach these days. Teaching just takes a lot of time that I really should be spending working in the studio. But on the rare occasion I do have classes or demos on the horizon, I always announce it on the events page and via my mailing list.

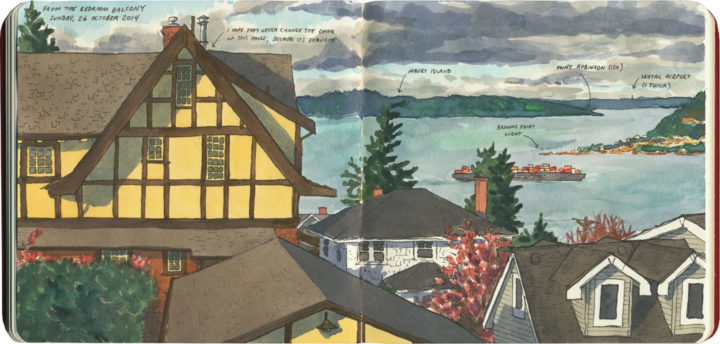

What about sketchbook classes? I want to learn to sketch, too—will you teach a class/create a how-to video/do a demo?

Once in a great while I teach live sketching classes, usually at the School of Visual Concepts in Seattle. As for video classes, I’m afraid not. Sketching is something I do on the side, in addition to my regular work. Since it’s something I have to fit into an already crazy schedule, that time is precious to me—I need to devote that time to drawing rather than filming videos or setting up online classes. I do, however, have a pretty extensive list of the materials and tools I use over at my Drawn the Road FAQ, if you’re looking for something to help nudge you out onto the sketching path.

But if you want to learn to sketch, that’s great! There are lots of ways to learn to draw—and the best one I know is to just get out there and try it. And try some more. And keep trying. Just draw and draw and draw—don’t worry about it being “good,” just worry about finding time to do it. Drawing is something that takes time to master, but the practicing is the fun part. Before you know it, you’ll have racked up a lot of time and more than a little expertise.

How about private tutorials/mentoring/critiques/brain-picking sessions? Public speaking?

Private sessions/tutorials/critiques/consulting are a little less rare than classes, but I get way more requests for them than I can possibly say yes to. If you’re interested in scheduling a formal one-on-one session at an hourly consulting rate, please feel free to contact me.

Public speaking, however, is something I do frequently. I’ve done lots of artist talks and panel discussions (both as moderator and panelist), and Jessica Spring and I have spoken about our Dead Feminists around the country. Most of my speaking engagements are open to the public and free to attendees. You can always find information about both past and upcoming talks on the events page—or if you’re interested in organizing a speaking engagement, drop me a line.

There’s an item I want to buy, and I know you offer it for sale, but I can’t find it in your shop. Why?

Sorry about that! One of the tricky things about having all these side projects is that it’s hard to condense everything into one place. Some of my items are available exclusively through retailers or galleries; others reside in a separate, dedicated online shop. (See the “How can I purchase your work” question above for links to my other online shops.) If you’re having trouble finding something, or you’d like to place an order that combines items from different shops, please feel free to contact me directly, and I’ll sort you right out.

I want to buy your book! Can I buy it directly from you?

Thank you so much, and yes! You can choose from the Dead Feminists book, Chandler’s Best Coast book, or the book of Best Coast postcards. However, if you would rather shop through your favorite bookstore, we are all for it! Since these books are distributed by Penguin/Random House, that means it’s available wherever books are sold. You can find links to various online retailers over at our book page.

How can I get my hands on a signed copy of your book?

If you choose to buy directly from us, here you’ll find links to the Dead Feminists book, Chandler’s Best Coast book, and the book of Best Coast postcards. Signed copies are also available from our local indie bookstore, King’s Books—and they can ship a signed book to you anywhere in the world.

I just placed an order in the shop. How long will my stuff take to arrive?

If you ordered an item that is in stock, I usually ship within 3 business days of your order. Many orders even ship the same day, thanks to the fact that I live in the Pacific time zone. Unless special arrangements are made, I ship all packages via the US Postal Service. If you purchased Priority or Express shipping with your order, I will send you a tracking number as soon as your order ships.

If you purchased a Special Order item, like a digital print that had to be made-to-order, please allow 7-10 days for your order to ship, as I have to have your item(s) specially made. Most giclee print orders, if I don’t already have the print in stock, ship within 1 week.

Wholesale orders usually ship within 3 business days, unless an item is backordered or special circumstances apply. For new stockists, pre-payment is required before an order can ship.

Do you ship overseas?

As of July 1, 2021: yes, to some countries. Please note that due to new European Union laws concerning import VAT, I am currently unable to sell or ship to EU customers. I am a one-person business, so I don’t currently have the bandwidth for managing VAT compliance. If and when that changes, I will post a new update here—I apologize for any inconvenience.

Unless special arrangements are requested, I ship all packages via USPS First Class or Priority (depending on size and weight) shipping. International shipping fees have increased precipitously over the past few years—I apologize for this, but USPS is still considerably less expensive than the commercial carriers. Unfortunately, I can’t control how fast or reliable international shipping is, as it depends upon many factors. Once items leave the U.S. they are not usually able to be tracked past their last location here—unless you request Global Express shipping, which costs extra. It’s possible that you may also be charged import taxes, customs fees, duties, or other charges by your home country when your package arrives. Unfortunately I can’t control when, where, why, or how customs agents might charge you these fees. All such fees are the responsibility of the customer. I mark all of my shipments “merchandise” on the customs form; I will not mark them as gifts because it is illegal—so please don’t ask.

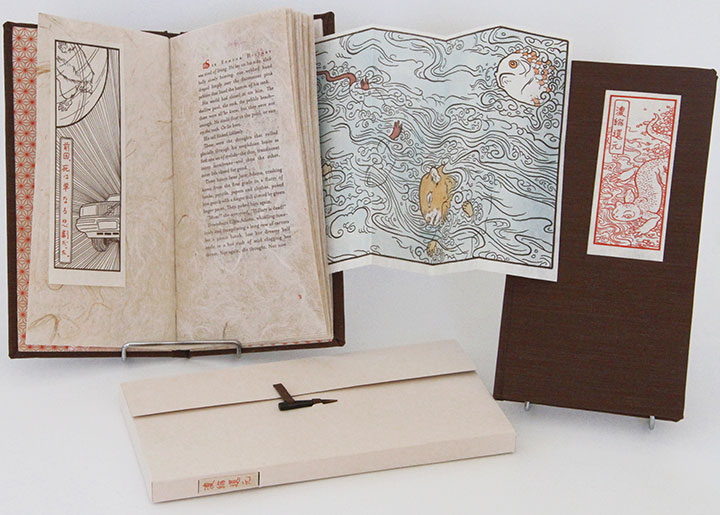

What are the book arts? What is an artist book? How is that different than a “real” book?

This book arts are a broad category of art that includes hand-bound books, handmade paper, letterpress prints and ephemera, and a wide variety of other work like installations, conceptual art, textiles, typographic work, sequential art and sculpture. The common thread is that the work usually has some sort of narrative, some form of sequence, multiple images or “pages,” often some quantity of text incorporated into the piece, and generally one or more handmade element.

What’s an artist book? Stephen Bury from the British Library explains it far better than I ever could: “Artists’ books are books or book-like objects over the final appearance of which an artist has had a high degree of control; where the book is intended as a work of art in itself.” What can be confusing is that an artist book (or livre d’artiste if’n you wanna git all museum-speak fancy) may not look like a book at all. (Mine often don’t!) But no matter what it looks like, an artist book does the job of both books and art. It tells a story, and it also stands alone as a piece of art in itself.

What is a broadside?

The great-grandmother of the poster, the broadside or broadsheet was one of the earliest forms of mass communication, usually containing important information. It dates back to the earliest days of printing—think Gutenberg Bible. (I once told this definition to someone, and they answered, “Wait, you mean Steve Guttenberg?” And then I died laughing.) The broadside also was an important political medium and early agent of social change—Martin Luther, for instance, has the broadside to thank for bringing about the Reformation 500 years ago. Nowadays, broadsides have become a favorite of the letterpress world, and been converted into its own art form, intentionally combining both images and text in the same piece. The social/political part of the format is still alive and well, too—it’s why Jessica Spring and I chose the medium of broadsides for our Dead Feminists series.

What’s the difference between a letterpress print and giclée print? Aren’t all prints the same?

This is a little hard to explain, and can be a touchy subject, depending on whom you ask. But in the most basic sense, a letterpress print (as well as a linocut, a wood engraving, an etching, a screen print, or any traditional printmaking medium) is a hand-pulled print. By “hand-pulled,” I mean that the print was created individually, by hand, from an original plate or block. Hand-pulled prints are very often created in limited editions of a small number of prints. Because of the labor involved, the limited quantity, and because the handmade part of the process makes each print slightly different than the others in the edition, these prints are called multiple originals. Basically, that means every print in the edition is considered an original work of art—not just a “copy.” Though the techniques might vary, printmaking has existed as a fine-art medium for centuries.

A giclée print, on the other hand, is a copy. The name (pronounced “GEE-clay”) comes from the French word for “spray,” referring to the digital printing process. A giclée print is a high-quality reproduction generated by a digital (inkjet or similar) printer, using long-lasting, lightfast, archival ink. You might see a giclée print that is numbered or marketed as “limited edition;” opinions vary about how valid this practice is. Personally, I believe the most important distinction is whether the piece was printed digitally or by hand—and that the customer/collector knows what it is that they’re buying. (For instance, I’ve seen reputable galleries pass off digitally-printed canvases as original paintings, and price them as such—a practice that I feel undermines the work that hand printmakers do, and cheats collectors who are looking for handmade originals.)

Both hand-pulled prints and giclées are valid media, and each has an important place in the art world. Giclées are especially important for reproducing digital artwork and the types of illustrations that can’t be created using traditional printmaking media. It’s just best to know for sure what you’re getting when you purchase that piece of artwork you fall in love with.

In my case, I create both original hand-pulled prints and digital giclée reproductions. However, I make sure that I always, always declare which is which. My hand-pulled letterpress and linocut prints are clearly marketed as multiple originals; they are always created in numbered limited editions, and I never reprint an edition once it sells out. My giclée reproductions are also clearly labeled as such, and they are never numbered. They also have a lower price point than the handmade originals I sell.

(Clear as mud, right?)

What font did you use for that poster/illustration/broadside?

My lettering work is hand-drawn, with pencil or pen, from scratch. Even work that ends up in a digital format starts out as a pencil or ink drawing. My letterforms and text styles might be influenced by a certain historical period/style and the “rules” of formal typography, but they’re all original designs. I don’t trace or copy existing typefaces—I draw my own. And that’s really the fun part about lettering: that every style of letterform has its own “voice,” and that creating your own type gives each piece so much more to say than just the words themselves.

How did you get started doing what you do?

I graduated with a BFA in Illustration from RISD (Rhode Island School of Design). My formal education was extremely interdisciplinary, and included everything from darkroom photography, character animation, comics, advertising, typography, illuminated manuscripts, screenprinting, plein-air painting, and street performance while wearing/operating a giant puppet (no, seriously!). I also spent a year in Rome making books and pretty much doing nothing but drawing and traveling. (And drawing while I travel. And eating Italian food.)

Outside of school, I spent six years building sets for summerstock theatre; three lonely summers sitting in a darkened room doing old-fashioned prepress paste-up with hot wax and a light box; five years working as a graphic designer in a Minneapolis firm; and a six-month stint doing production design from CAD blueprints at a tractor decal print in North Dakota. I restored a two-story vintage outdoor whiskey ad (with six-foot type and my crippling fear of heights); dusted shelves of Alvar Aalto vases and stacked bolts of Marimekko fabric at a Finnish design shop; answered phones at an architecture studio; worked as artist-in-residence at Minnesota Center for Book Arts; taught letterpress printing in the mountains of North Carolina; learned to weave on a four-heddle floor loom; catalogued countless hundred-year-old chemical bottles in a university laboratory; took a community-ed class about steam locomotives; designed permanent public art pieces for a light rail station and a waterfront pier; and spent (so far) nearly fifteen years running a small business by the seat of my pants. Oh, and when I was ten, I made huge illustrated signs that I brought to college hockey games to cheer on my favorite team. That introduced me to lettering … and a whole lot of Division One hockey players.

You’d be amazed at how interrelated all these things are.

The point is, my path might have been a meandering one, but none of the skills and experiences picked up along the way has been a red herring or a dead end. Nothing is ever wasted—everything I’ve ever done, in some way, has had a role in bringing me here, to where I am now. And what I’m doing now will lead me to whatever is next, just beyond the horizon.

Where are you located?

I work in my home studio in Tacoma, Washington—about forty minutes south of Seattle and two hours north of Portland. Which is kind of like being the mayo in a hipster sandwich sometimes, but that’s okay: I like mayo. Tacoma is a stunningly beautiful, arts-friendly small city, where people say hello to you on the street—because folks here are some of the nicest on earth. It also doesn’t rain here as much as you think.

Can I come visit your studio?

My work space is not open to the public—which allows me to do things like make giant paint messes, talk to myself, and work in my pajamas. However, I do make the occasional visit appointment with customers/clients/colleagues (for whom I wear nicer clothes than pajamas), and every fall I open my studio as part of the annual Tacoma Studio Tour weekend (I actually dress up for that!). If you want to stay on top of when Studio Tour and other events happen, I recommend the mailing list!

Can I be your intern?

I work in a teeny-tiny space, often creating very intricate projects that demand a lot of time and technical skill. I really need to work alone so I can natter on to myself and concentrate slavishly (sometimes while simultaneously freak-dancing to the Talking Heads), without an audience or interruptions. My studio and systems just aren’t a great match for an internship—I’m sorry not to be more helpful.

Will you donate work for my art auction?

At this point, only if I already have an established relationship with your organization, or it’s a very special circumstance. I am not exaggerating when I say I could literally paper every wall in my house with the auction donation request letters I receive every year. To be perfectly honest, most artists would much rather write a check to the causes we support than be asked to donate our work. Auctions are so common these days that the market is oversaturated—they’re also, in general, economically detrimental to the artists and arts communities they’re meant to encourage. Of course, some auctions are extremely reputable and beneficial to all parties involved; but these rare birds are the exception rather than the rule. Unlike, well, any other professionals, artists cannot legally deduct the market value of the work we donate —only the cost of materials (we can thank Richard Nixon for that—no, seriously! He donated his personal papers in 1968, took a huge tax deduction for their “fair market value,” and the tax law was changed in 1969 as a result, to prevent artists from “painting their own tax dedution” each year). The “exposure” and referrals we’re promised in return are minimal to nonexistent. And auction-savvy art buyers often view these events as an opportunity to bargain-shop—which results in both devaluing the artist’s work and lackluster fundraising results for the organization. In light of this, I’ve become very choosy about when and if I contribute artwork to an auction—and in most cases I have a minimum bid, a reserve that must be met, and a commission percentage on the sale price. Even so, I still make many donations of artwork and stationery goods, pro bono commissions and, most often, monetary contributions (especially through the Dead Feminists series) each year, so I’m usually booked up by the time new requests arrive. I hope you’ll understand.

Can I write a guest/sponsored post or put my image/graphic/link/promo/advertisement on your blog?

No. Sorry/not sorry.

Still, despite this site having zero ads or sponsored content of any kind, and the above answer, I still get about a zillion requests for sponsored content every year. Because I’m tired of wasting my breath and my time, all requests for advertising/sponsored content will be marked as spam and ignored. No exceptions.

Occasionally on this site I will link to a book or art material on Amazon. As an Amazon Associate I earn a small commission from qualifying purchases, via their affiliate program. That is the only form of advertising you will ever find on this site (other than my own shameless self-promotion, of course…). I don’t accept outside content from anyone, and all of my opinions and recommendations are my own.

The Amazon affiliate link for our book, Dead Feminists: Historical Heroines in Living Color, is special. Any monetary commissions we receive from that link will be donated in full to the Dead Feminists Fund, our foundation which supports nonprofits that empower girls and women to effect change in their own communities.

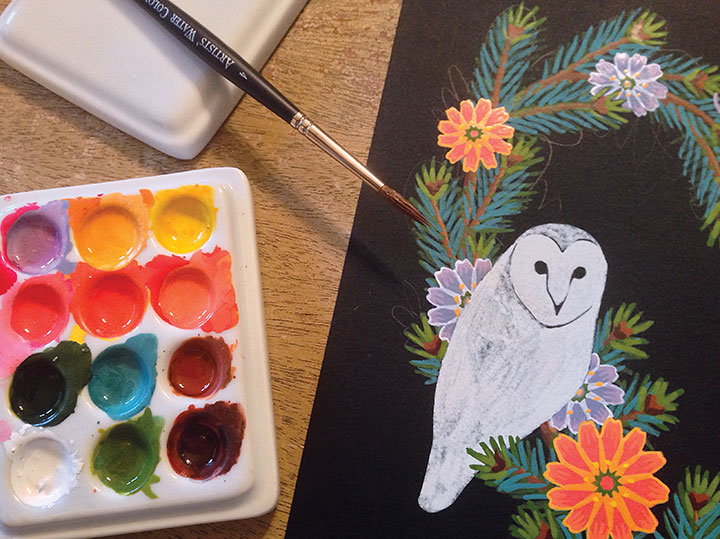

What kind of pencil/pen/paints/paper/sketchbooks/camera/other materials do you use?

I work in a wide variety of media—far too many to list in any depth here. I do explain a lot about my process and materials on the blog, though, if you’re interested. And since I’m asked on an almost daily basis, I did a lengthy and very specific description of the materials I use in my travel sketches.

Everything I do involves some sort of handwork (either as one ingredient or the entire project from start to finish). And every single piece I’ve ever done begins with a drawing—with plain old pencil/pen and paper. This goes for everything from logos to paintings to book design to sketchbooks to public art. I also really like art history and good, old-fashioned inquiry—so there’s a lot of research behind every project I undertake.

People ask me all the time if I use French curves in my lettering, or clip art/found imagery in my illustrations, or a fancy Wacom Cintiq tablet for my digital stuff. I don’t. They’re just not my thing. I like to keep my tools as simple as possible—my most reliable are pencil, pen, brush, blade, hand and eyeball. That’s not to say that French curves and fancy tablets aren’t nice things to have—and for as Luddite as I might seem sometimes, I sure love my Adobe software. In the end, though, I’m not sure it matters what brand of gouache you buy, or how old someone’s press is, or how I feel about analog vs. digital photography. I think what matters is what you do with whatever materials and tools you choose—and taking the time to experiment and learn. A two-thousand-dollar camera isn’t going to make you better photographer. A certain type of pencil isn’t going to give you previously unheard-of drawing skills. These things come with time and practice—not with bells and whistles.

Where does your inspiration come from?

Everywhere. Often from things that have nothing to do with art—a walk on the beach, an essay I read, a building I passed, a history textbook, a 19th-century novel, a knitting basket, a scientific article, a taco truck. But I am also an avid student of art (and non-art) history—and I’m influenced by everything from illuminated manuscripts to Scandinavian textiles to Japanese prints to mid-century animation to Islamic tilework to Central American folk art to Baroque sculpture to Dutch painters. The list is endless—which I think is as it should be. The world is full of wonderful things that humans have created, and I think we’d all do better work if we did more to learn about those things.

The one thing I actively try to avoid when I’m researching something is looking at the work of my colleagues and contemporaries. I’m not interested in spinning off of what someone else has worked hard to create, or create work that “looks like” some well-known artist’s style. And heaven knows I bristle whenever someone tells me they’re creating work (or commissioning it from someone else) that’s “just like” something I did (imitation, from the perspective of the imitated, is not the sincerest form of flattery—it’s the sincerest form of sucker punch). As it is, it’s already too easy to follow a trend or stumble upon an idea that’s already been done. So while there are many, many artists that I either know or admire (or both!), I make a concerted effort to give them a wide berth and “turn off the faucet” when I’m looking to develop an idea. Instead, I turn to history, or nature, or one of the many things that don’t directly fall under the “art” category—and that method has served me well.

What is your process like?

As I said, I almost always start in pencil, and I often do a lot of historical research. But I almost never do multiple working drawings or rough drafts, unless I do a sketchbook drawing that is meant to stand alone as a finished piece (I’m a big believer that sketches are art in and of themselves.). For everything else, usually I do a quick thumbnail sketch (the intelligibility of which depends on whether anyone besides me needs to see and make sense of it), and then proceed straight to the final piece. Sometimes there are necessary intermediate steps, like inking over a pencil drawing or converting a pen line to vector format, but all of those things are part of making the final product. I’m just not the type to do endless rough drafts—I like to make a decision and run with it.

On the blog you sometimes mention someone named “the Tailor.” Who is that?

The Tailor is my spouse, so named because he makes his own clothing. He’s also a scientist, an amazing cook and a brilliant tinkerer. Anyway, out of respect for his wishes and privacy, I refer to him online only by his pseudonym.

What do you do when you’re not working?

The Tailor and I are a household of makers! We make stuff. All the time. So when we’re not working, we’re usually doing things that other people tend to view as… work. I write. He bakes. I knit. He cans tomato sauce. I embroider. He builds things. I shoot photos. He drafts patterns. We garden. But when your life and your work blur and blend and bleed together in a really delicious and fun way, this is how things are. And when it’s something you really love, it really doesn’t feel like work—it feels like an extremely fulfilling life.

We also travel. A lot. Especially me. If I could somehow travel every day of my existence, and still have my home life and career, I’d do it. While I travel (and even when I don’t), I carry a sketchbook with me everywhere I go. Drawing everything around me, all the time, for work and for pleasure, for nearly all my life, has shaped my work and my worldview like nothing else has.

Do you have any advice for newbie artists?

Spend your energy doing, developing and promoting the thing(s) you love the most—rather than what you think you “should” be doing, or chasing what’s trendy/popular/ubiquitous, or copying/overly emulating somebody else’s work. Of course, we all have to do common-sense things like paying the bills, meeting deadlines and balancing work/home life—but there are lots of ways to do those things and still be true to yourself. If you, whenever possible, can put your time into honing the work you really love to do, the work that is truly you—that’s what people are going to respond to. And work leads to more work—if all anyone sees are those corporate Powerpoint templates you keep getting roped into doing, it’s just going to lead to more Powerpoint templates, and you’ll become known as the go-to Powerpoint Queen. If nobody knows that your secret passion is, I don’t know, creating wooden marionettes or miniature crocheted altarpieces or something, paid work in that category will never land in your lap. Would you rather be known for that thing you love to do, or the work you’re good at but hate doing? Do what you love, your own authentic work (not someone else’s!), learn to do it well, and put that work out there into the world: your audience will come.

Are you ever capable of brevity?

When needs must!

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)