Blog

August 31st, 2010

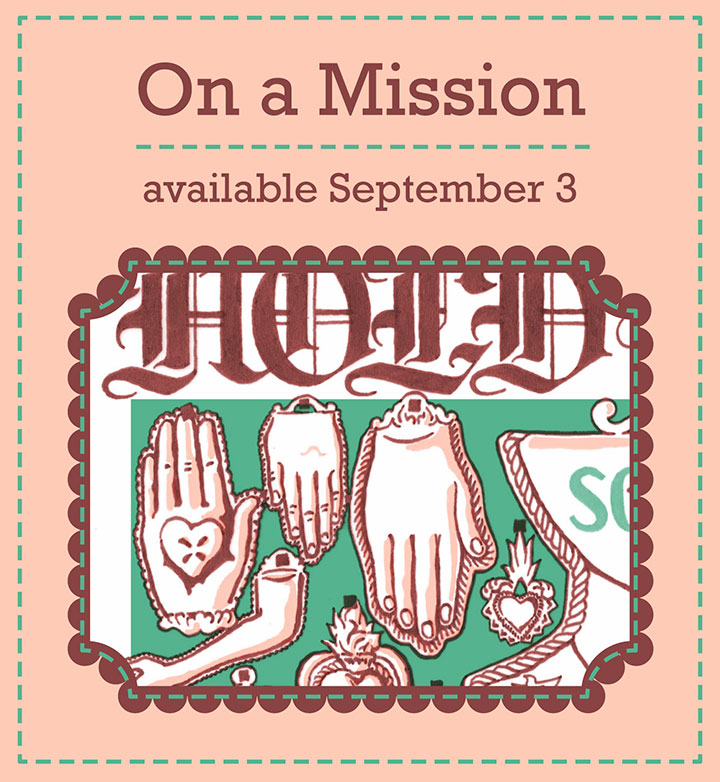

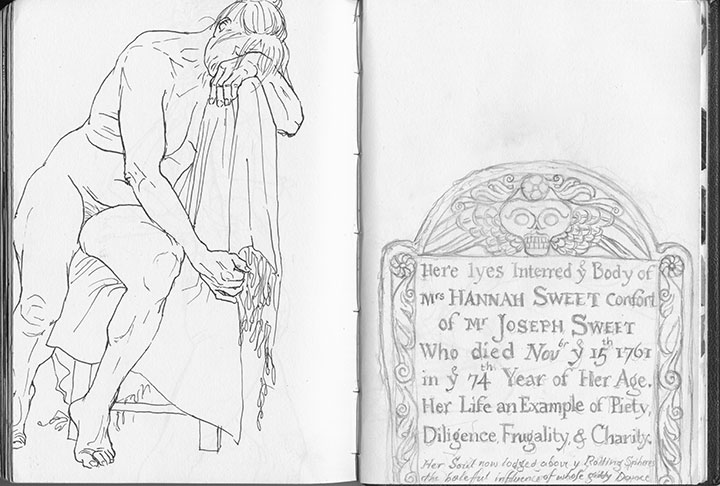

At the Wayzgoose on Saturday (thanks to the hundreds of folks who showed up!), Jessica and I had a little teaser for the next Dead Feminist print set up at our table—I figured it wouldn’t be fair if I didn’t also share it online.

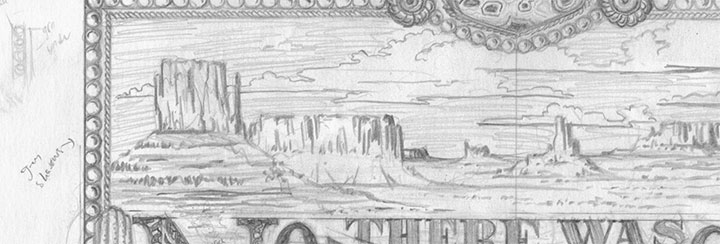

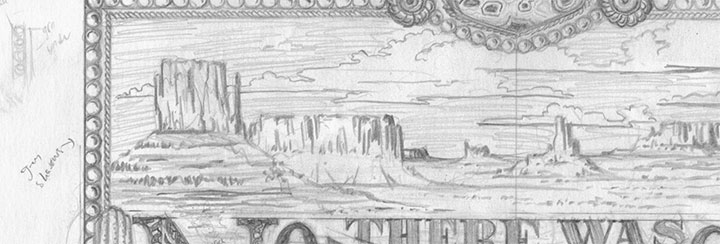

I’m not going to say much, so as not to spoil the surprise, but I thought I’d drop a few clues by way of my messy drawings—

warts and all. As you can see by all the smudges and arrows, doin’ it by hand is hardly a perfect process,

but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

On a Mission is on press as I speak, inching closer to the finish line every moment. Look for it here on Friday—see you then!

August 25th, 2010

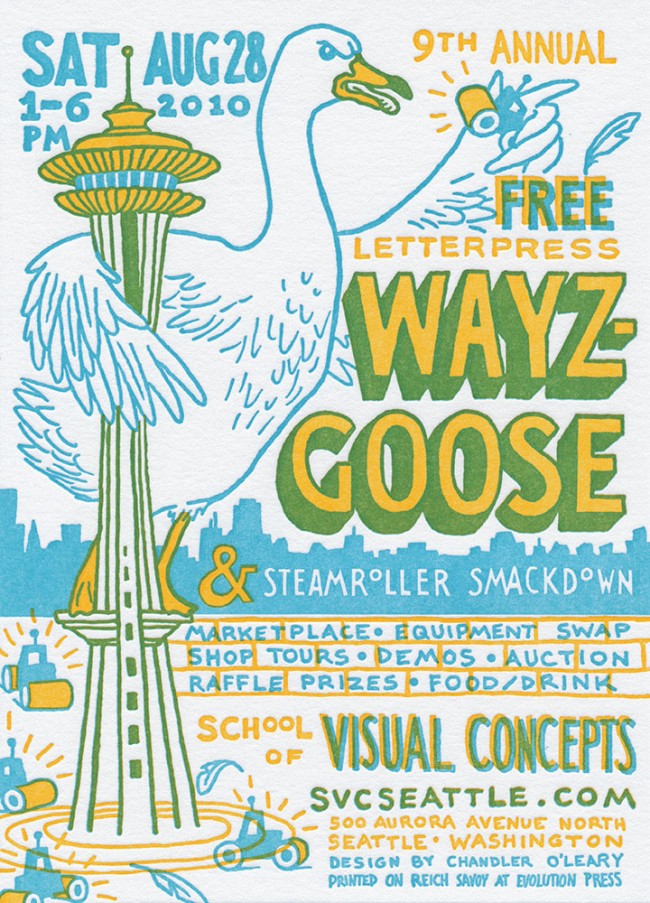

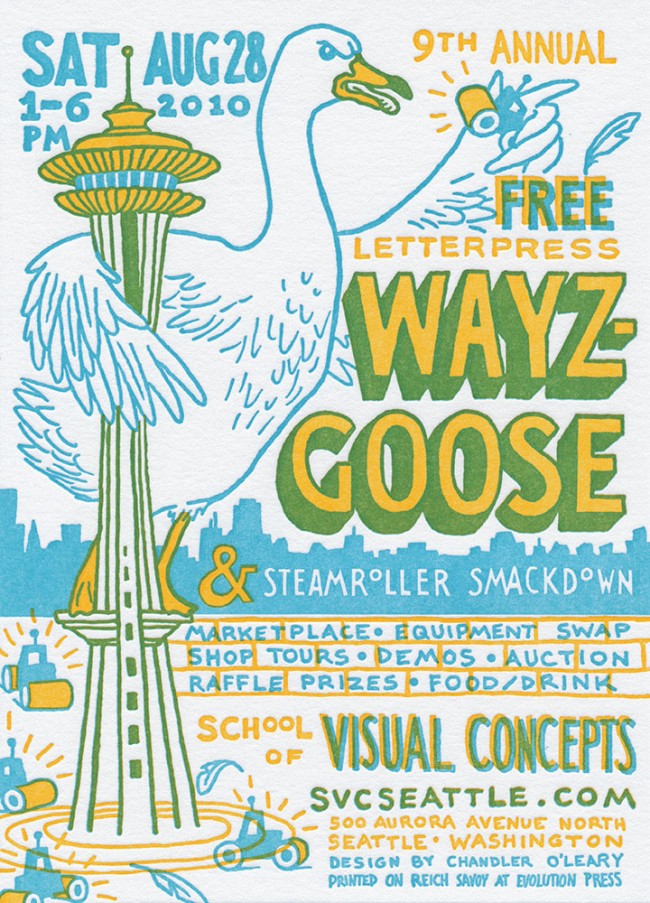

Jessica and I are waist-deep in the new Dead Feminist print (look for it here next week), so I’m just popping in to wave hello—and to warn you, in badly-dubbed English, about the giant goose climbing the Space Needle.

Just kidding … but they will be sending in the steamrollers. This Saturday, in the Needle’s mighty shadow, is Seattle’s biggest letterpress party of the year: Wayzgoose. The weather is supposed to be perfect, so come on over and say hi to scads of letterpress artists, print your very own keepsake in the studios, and referee the Steamroller Smackdown outside. Jessica and I won’t be steamrolling this time, but we will have a table in the marketplace—so don’t be a stranger!

Here’s the skinny:

9th Annual Seattle Wayzgoose

Saturday, August 28, 2010

1 to 6 pm

Free!

School of Visual Concepts

500 Aurora Avenue North, Seattle

More information and RSVP here

The lovely ‘Goose wranglers at SVC asked me to design this year’s postcard; I think I was watching too many Japanese monster movies at the time. But monsters and letterpress seem to go well together; the postcard is lovingly letterpress printed by the talented titans at Evolution Press

August 21st, 2010

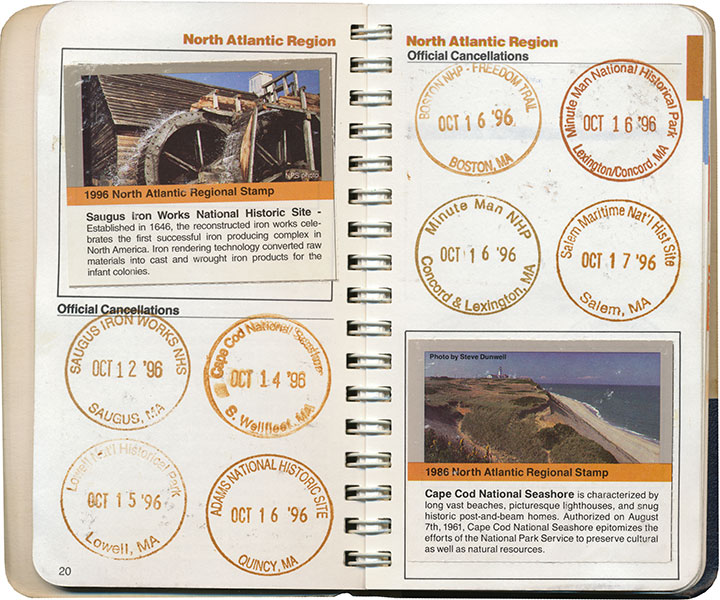

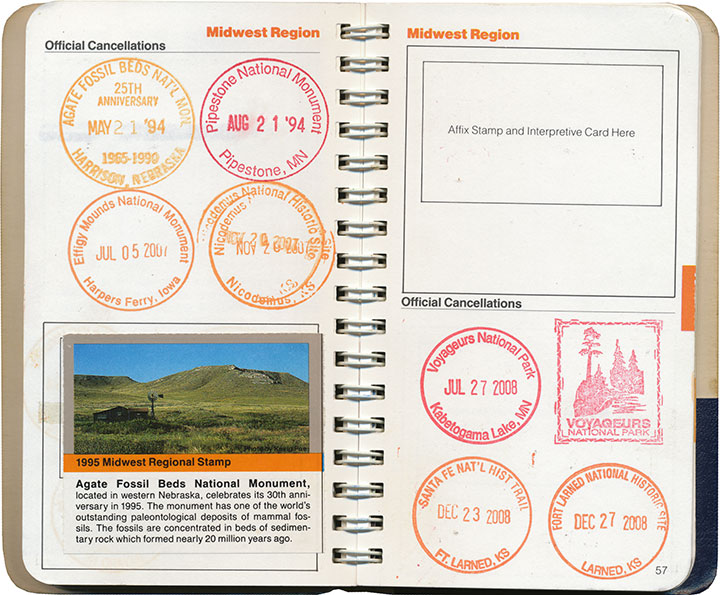

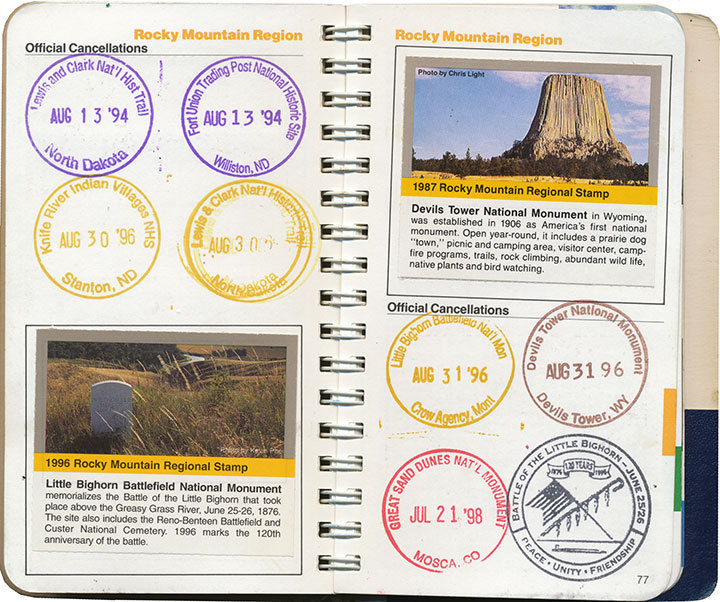

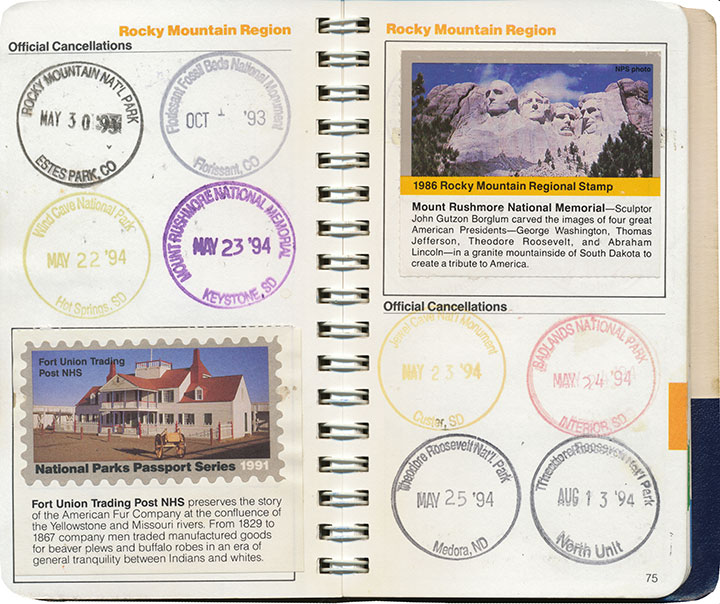

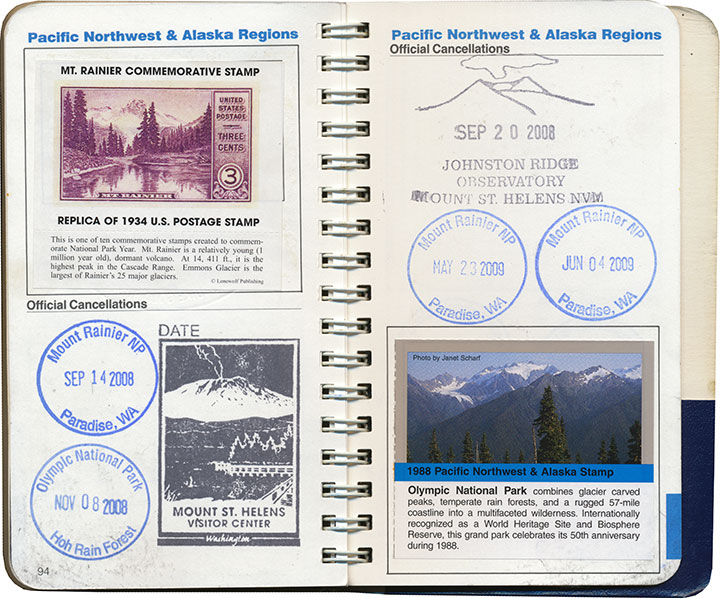

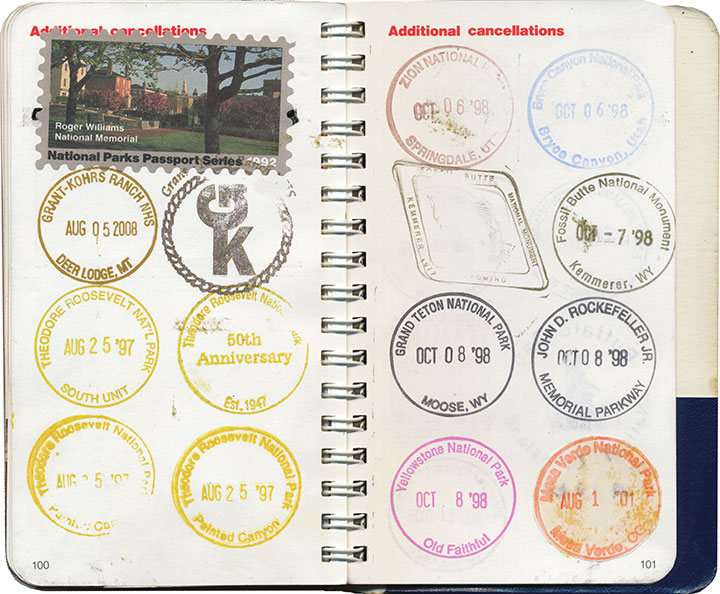

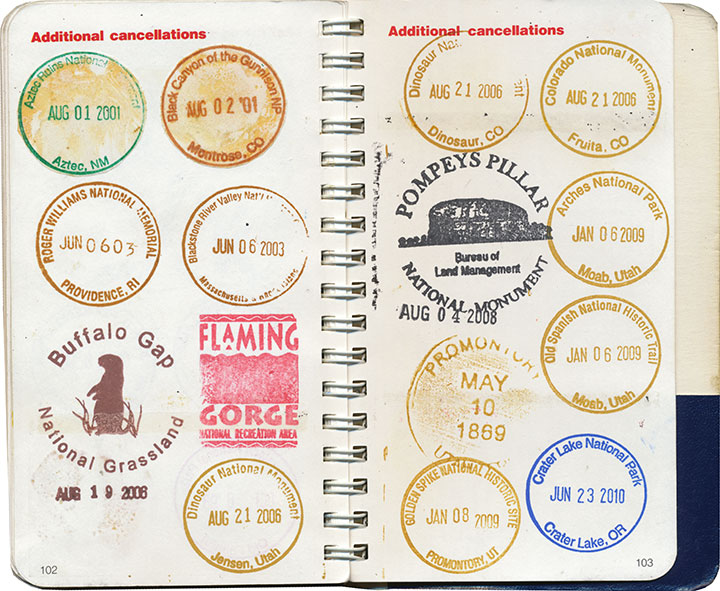

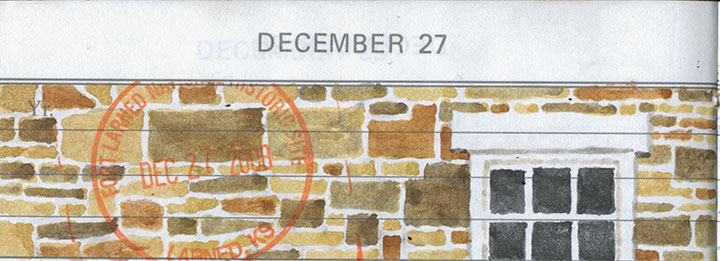

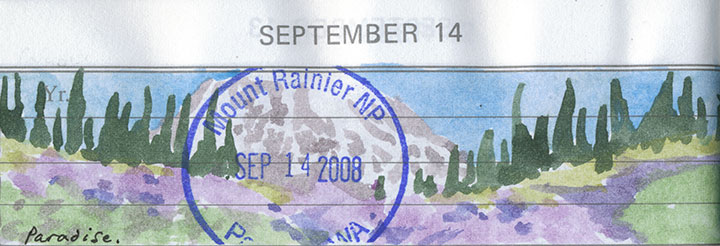

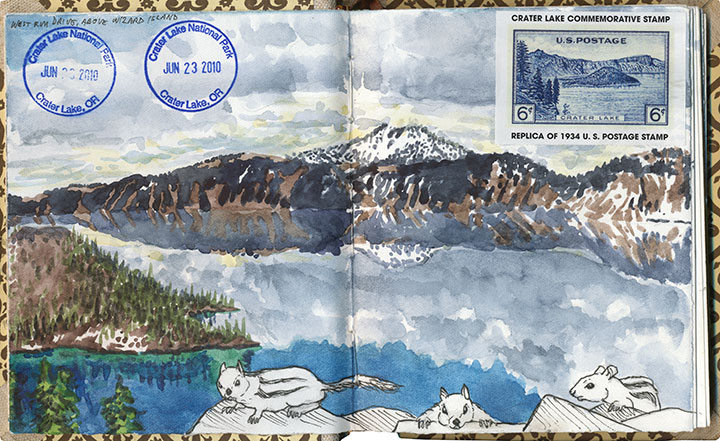

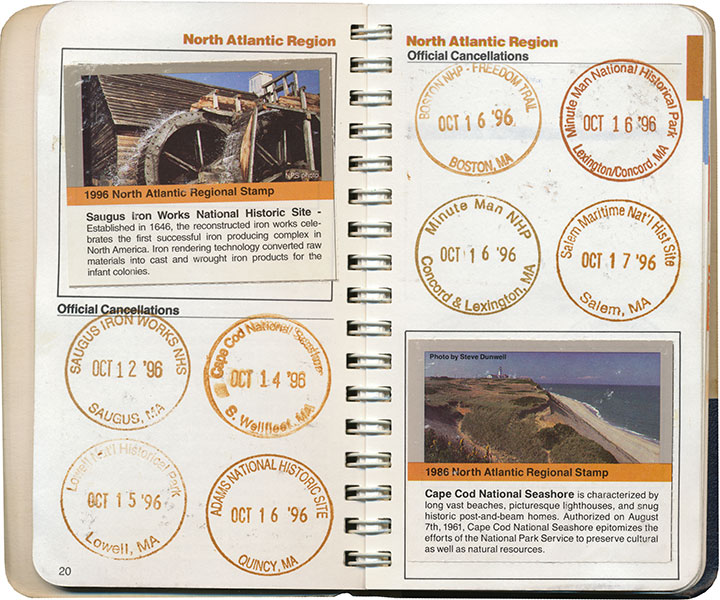

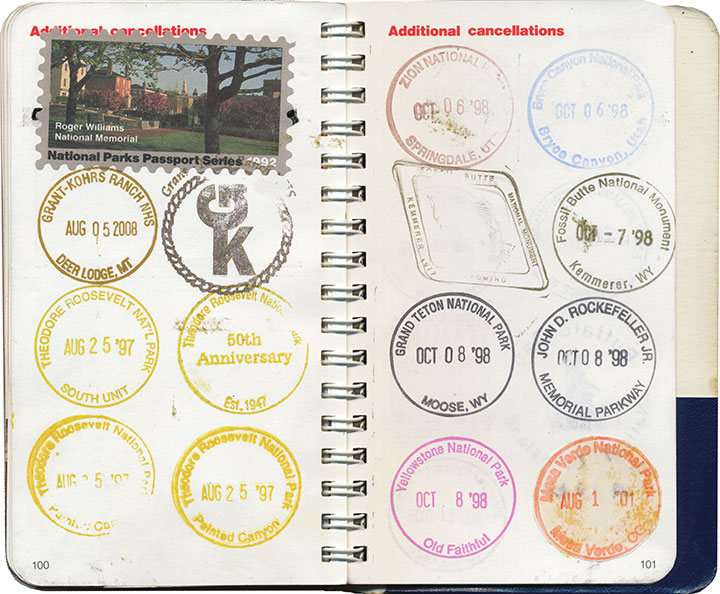

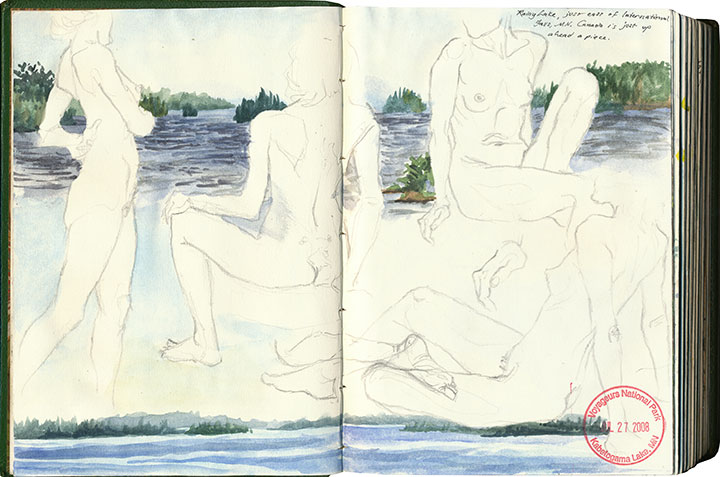

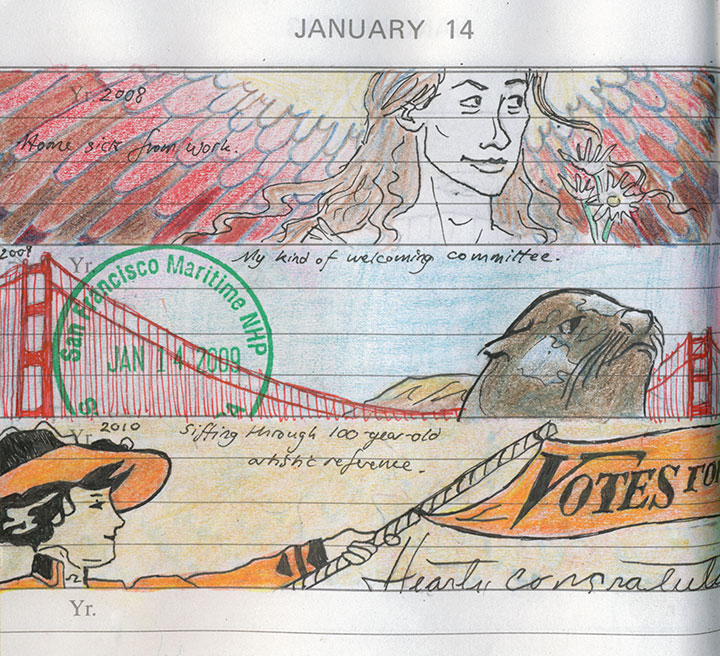

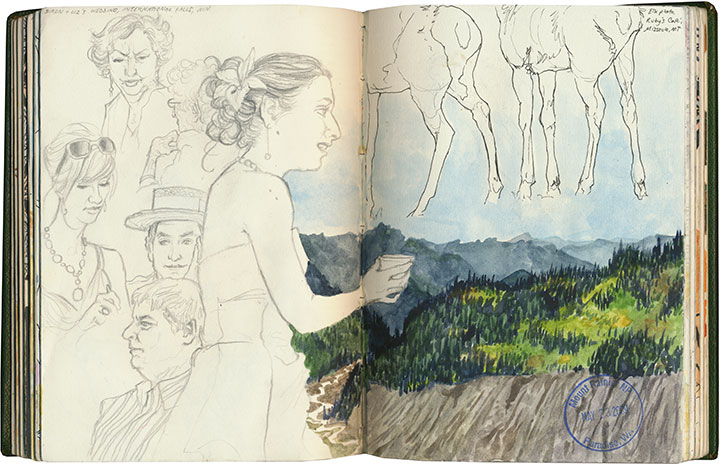

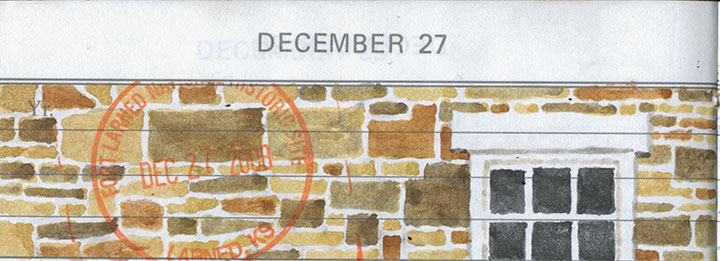

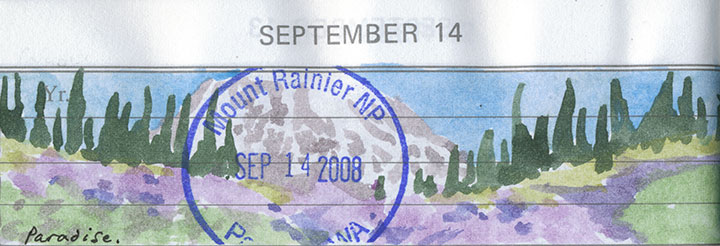

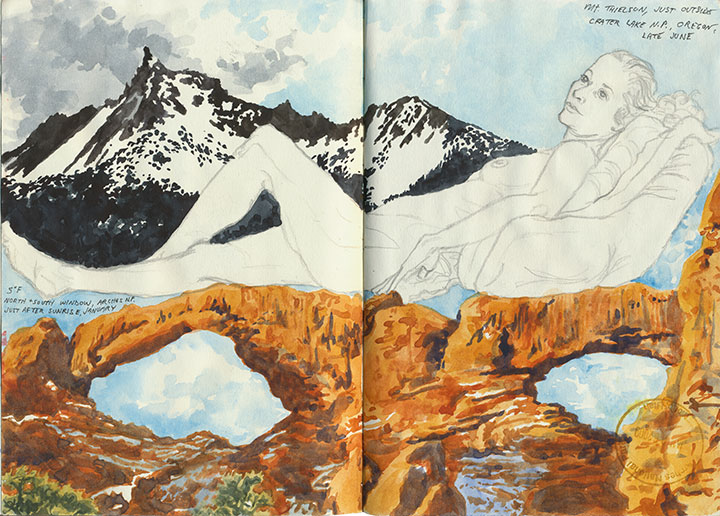

Since I posted this drawing and some others this summer, people have been asking me what’s with the stamps in my sketchbook. I guess the short answer is that each one is a little piece of personal tradition.

But you know I don’t really do short answers.

The long one, then.

I grew up in a nomadic family. Between the moves required by Dad’s job in the Air Force and a fierce wanderlust that runs in all the O’Leary veins, we had a lot of reasons to travel. Dad and I, especially, would spend hours poring over our dog-eared Rand McNally road atlas, plotting routes over the back-est of back roads (the squigglier the line on the map, the better) and stops at as many points of interests as we could cram into a journey from A to B.

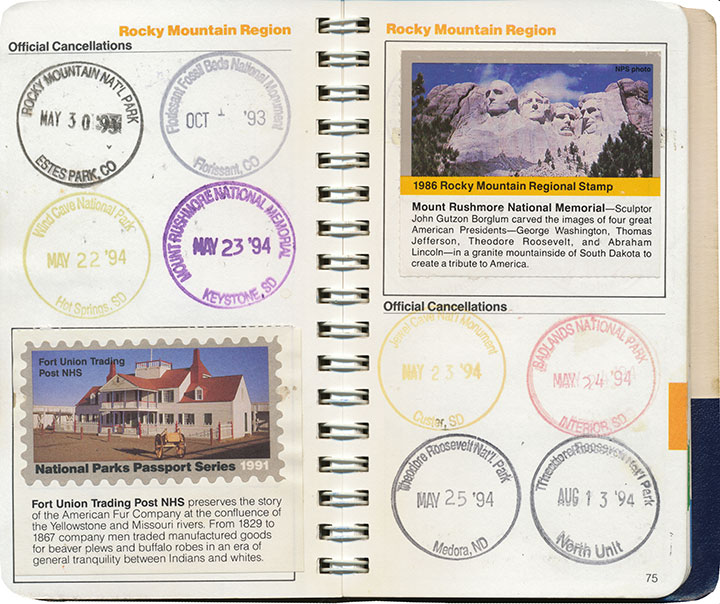

When I was ten, we made a circuit of our then-home state of Colorado, and devoted our time to exploring every national park and monument we could reach along the loop. At each park’s visitor center, we noticed a rubber stamp and ink pad stationed at the front desk. When we finally asked a ranger what they were for, she handed us a small blue notebook and proceeded to explain about the National Park Service’s Passport program.

A stamp to collect at every NPS property in the country, and a tidy little book to hold them all? I was hooked.

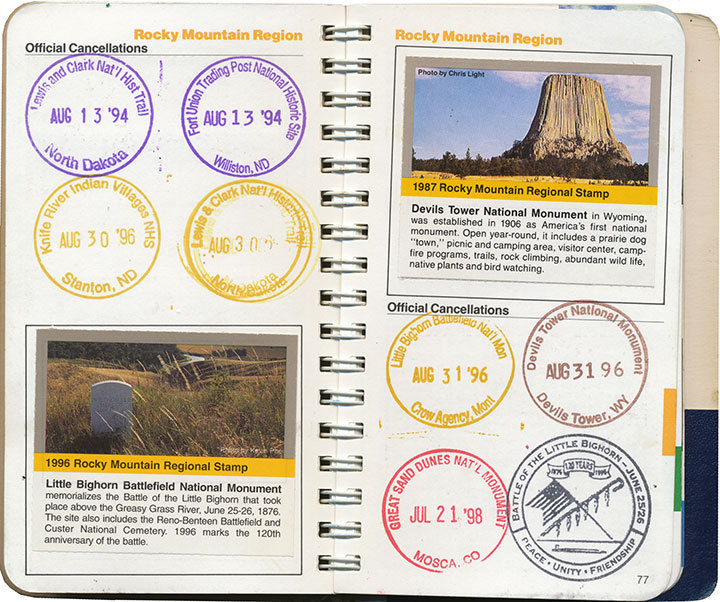

Dad and I found ways to sneak a national monument or two into every road trip and relocation—and even took impromptu vacations just to add a new park to the list. My favorite memory is when I was in high school, and Dad popped his head into my room:

“Have any plans this weekend?”

“Uh, no…”

“Wanna go to Montana?”

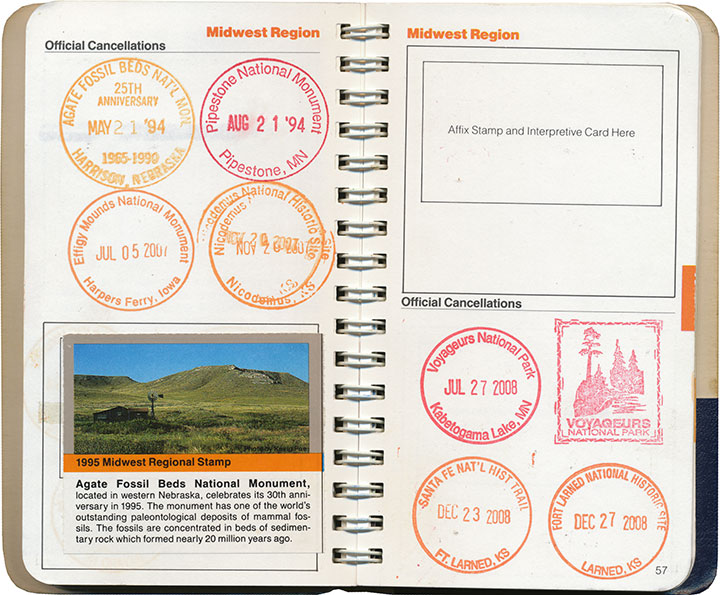

So we jumped in the car and drove 600 miles just to flip General Custer the bird at Little Bighorn (I had just read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, so he wasn’t exactly stirring me to patriotism). I mean, if you’re going to do it, you might as well go all out, after all. And we had the stamp to commemorate the moment.

The Passport program also includes collectible paper stamps, which can be purchased from afar (as opposed to the ink cancellations, which are free but can only be obtained in person). I’m pretty lukewarm about these, though; by the time I jumped on the bandwagon they had already phased out the super-cool two-piece design pictured in the lower left corner above, in favor of the cheaper, lower-quality one-piece stamp in the upper right. Since those have been revamped yet again into a pressure-adhesive sticker—and who knows what heinously non-archival chemicals might be in the glue—I’m even less of a completist about them now.

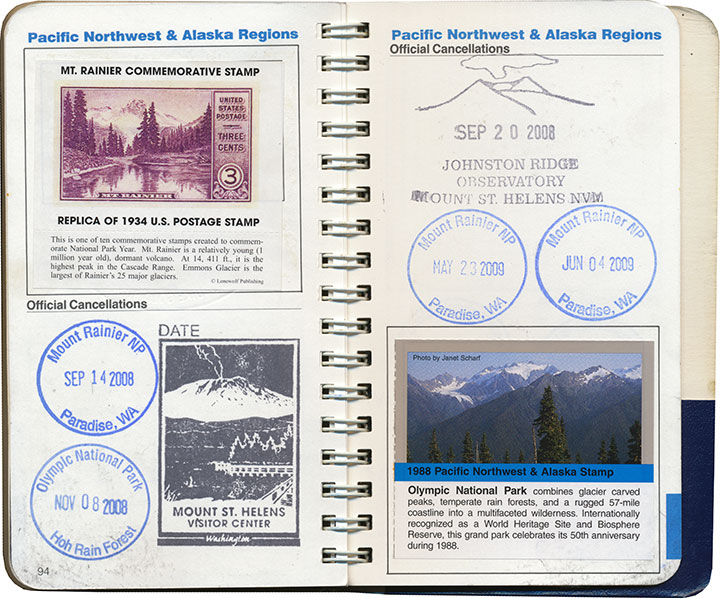

Anyway, I’ve burned through most of the regional sections in my Passport,

and every inch of overflow space.

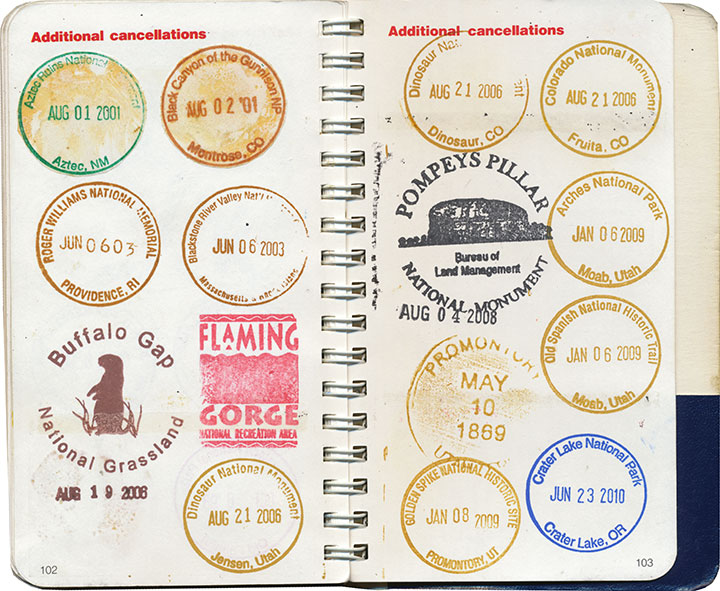

So I’ve branched out a bit.

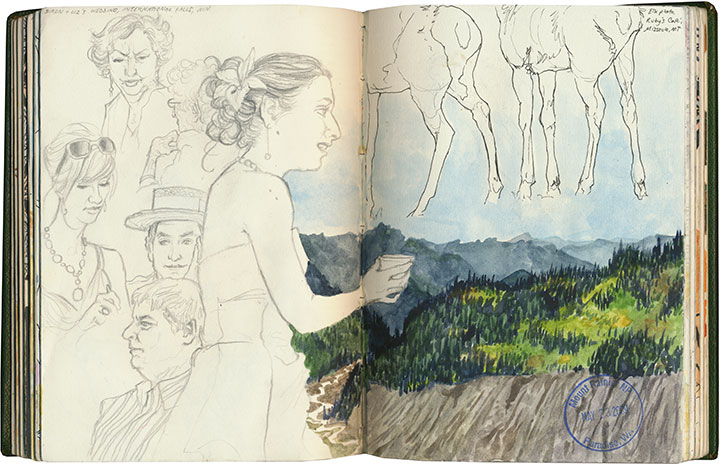

What I didn’t know as a kid was that my Passport helped me develop my interest in nearly everything I love most: traveling, design, archiving, printmaking, history, typography, bookmaking, and so on.

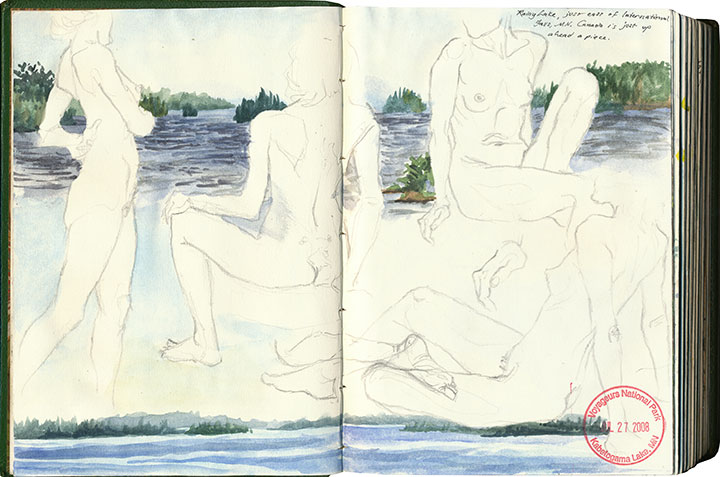

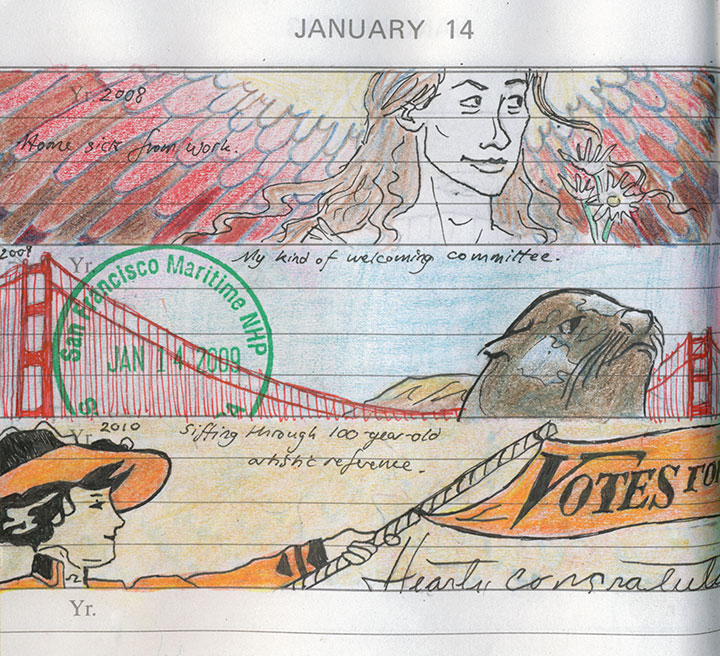

At some point along the way, I realized that what I really mattered to me (beyond the travel itself) was the act of adding to an ongoing work—and then looking back to see what I had accomplished. That what I had been doing all along, by compiling this little individual history, is creating some form of artist book. And that my frustrations over an imperfect format were really a desire to create my own.

A page from my daily book—more on that here.

So now all of my sketchbooks are Passports, each custom-tailored—

each infinitely flexible, ready for whatever adventures wait to be documented.

Here it is, nearly twenty years later, and I’m as eager as ever. Moreover, it’s my goal to collect every last cancellation within the entire National Park System before I stamp the big passport book in the sky. I’m about a quarter of the way there.

And I’ll probably have to build a library for all the sketchbooks I’ll fill between now and then.

Save

August 15th, 2010

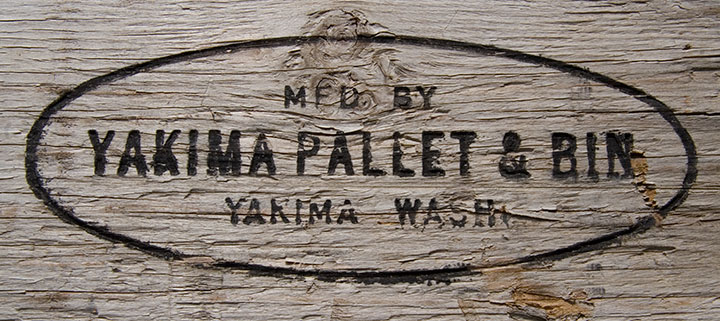

Earlier this month, my best friend Elizabeth flew in for a visit. Each time she’s come to town I’ve taken her to see a different part of the state—and since we’re in the middle of fruit season, this time we headed for the Yakima Valley.

At this time of year, the roadsides are piled high with apple crates,

ready for the harvest that will begin in a few weeks.

The pears seem to be a little closer—

they’re ripening quite nicely.

Right now, though, it’s peach season. The Tailor sent us on an errand for as much preserve-ready fruit as we could get our hands on—so I took him literally and brought home fifty pounds of Regina peaches,

another fifty of Rival apricots,

and a handful of beautiful donuts for a snack.

Once he got over his shock at the trunk full of fruit, and set aside a few peaches for the pie I had been begging for, the Tailor canned up an impressive array of preserves. From top left forward: peach jam; ginger-peach chutney (a collaboration with Jessica); sliced peaches in medium syrup; apricot jam; apricot sauce.

My favorite, and the one I can’t wait to taste with a little kugel:

Apricot Jam

(yield: about 10 half-pint jars)

– 2 quarts (8 cups) crushed, peeled apricots

– 6 cups sugar

Now, I’m not going to go into great detail about the whys and wherefores of home canning now, but if canning’s your thing, this will be old hat for you anyway. If not, and you’d like more specific instructions, I’d suggest our favorite resource: Putting Food By.

Anyway. Wash your jars in hot water (most books will tell you to sterilize them, but that’s what the hot water bath at the end is for). Keep the jars hot in a low oven (if you pour hot jam into cold jars, the glass can shatter), and the lids sterile in boiling water until ready to use.

Combine the apricots and sugar in a large stock pot. Slowly bring to a boil, stirring occasionally until the sugar dissolves. Cook at a rapid boil until thick (when the mixture reaches about 220° F, depending on your preference), about an hour, stirring frequently to prevent sticking or scorching.

When the mixture jells, pour it into the hot jars, leaving a 1/4-inch headspace in each. Wipe the jar rims with a clean cloth (any jam left on the rim will prevent the jar from sealing), attach lids, and tighten ring bands. Process in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes (longer if you live at high altitude).

Let cool for 12 hours before removing the ring bands. Store in a dark, dry, cool place.

(Or, if you just can’t wait, pop open a jar and have some toast ready.)

August 11th, 2010

I’ve been sitting on this post for months now—it’s just that after spending so much time hunched over this project, I needed some time off from even thinking about it. But now I’m ready to talk birds again.

From left: Cedar Waxwing; Steller’s Jay; American Avocet; Purple Martin; Tufted Puffin

Eighteen months, twenty-five birds, six hundred twenty-five individual prints and ten box sets later, my little Flock is finished.

Mountain Quail; American Bittern; Long-billed Curlew; Hooded Merganser; Laysan Albatross

Barn Owl; American Kestrel; Eurasian Coot; Anna’s Hummingbird; Herring Gull

It’s a little crazy to see these all together, like, well, birds on a wire. Each one has been broken down into its own little assembly line for so long that I forget sometimes to see them as a set.

Western Tanager; Lazuli Bunting; Northern Flicker; Bullock’s Oriole; Belted Kingfisher

Common Loon; Marbled Murrelet; Northern Shoveler; Harlequin Duck; Brown Pelican

As you can see, what’s represented here is a pretty broad cross-section of Washington birds. There are so many bird species ’round these parts, in fact, that I almost didn’t know where to start—and narrowing the choices down to twenty-five was by far the most difficult task.

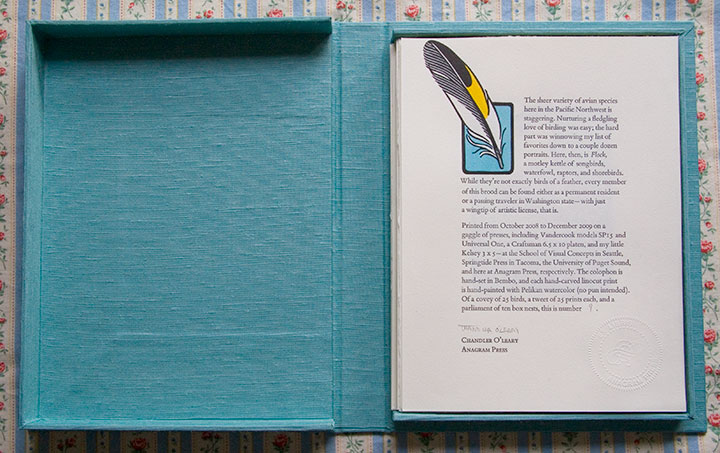

Wait. I take that back. The hardest part was keeping the glue off of the pricey imported Japanese book cloth (glue plus cloth equals death—or at least wailing, gnashing of teeth, and starting all over from the beginning).

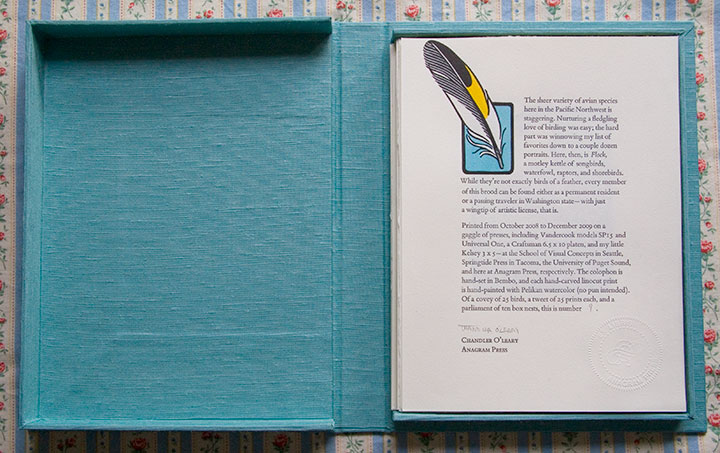

You see, it seemed silly to have a set of prints with nothing to house it. My inner book artist took over (thanks to Jessica’s tricksy enabling), and insisted on encasing the first ten sets of the edition in handmade clamshell boxes.

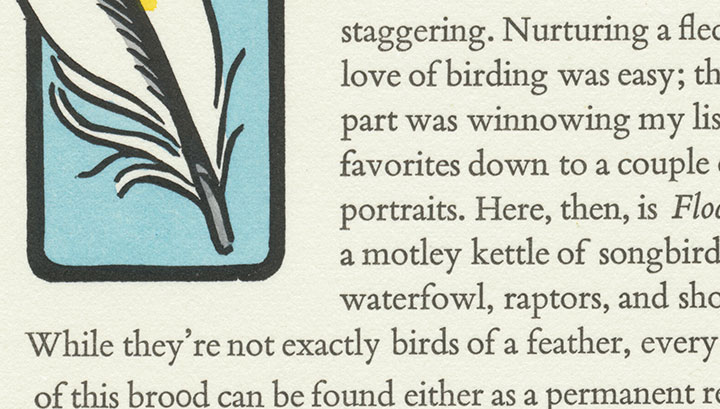

Even though the results are always worth it, I don’t have much love for making boxes—what I do love is printing the colophon. A colophon (or in today’s hardbound novels, the “note on the text”) is an essential element in any artist’s book; this is where the artist steps outside the book’s content and talks about the making of the book itself. For this I decided to go back to my letterpress roots, and hand-set the text in metal type.

While I’m rarely able to fit hand-setting into my projects these days (a drawback to all the lettering I’ve been doing), it’s still my favorite method of getting a block of text onto a page. And this beloved Bembo, cast locally at Stern & Faye, is so beautifully spaced and balanced that it’s a dream to set and a pleasure to read.

Here’s what it says:

The sheer variety of avian species here in the Pacific Northwest is staggering. Nurturing a fledgling love of birding was easy; the hard part was winnowing my list of favorites down to a couple dozen portraits. Here, then, is Flock, a motley kettle of songbirds, waterfowl, raptors, and shorebirds. While they’re not exactly birds of a feather, every member of this brood can be found either as a permanent resident or a passing traveler in Washington state—with just a wingtip of artistic license, that is.

Printed from October 2008 to December 2009 on a gaggle of presses, including Vandercook models SP15 and Universal One, a Craftsman 6.5 x 10 platen, and my little Kelsey 3 x 5—at the School of Visual Concepts in Seattle, Springtide Press in Tacoma, the University of Puget Sound, and here at Anagram Press, respectively. The colophon is hand-set in Bembo, and each hand-carved linocut print is hand-painted with Pelikan watercolor (no pun intended). Of a covey of 25 birds, a tweet of 25 prints each, and a parliament of ten box nests, this is number [2].

Okay, so maybe I went a bit overboard on the avian puns. It’s just that the thought of getting my hands dirty on type drawers again had me all twitterpated.

And I have a fluttering feeling that there might be even more birds in my future—one of these days, anyway.

August 6th, 2010

My goodness, how time flies.

As of this moment, I’ve been a Tacoman for exactly two years. Twenty-four months. Seven hundred thirty days. Seventeen thousand five hundred twenty hours.

And counting.

I’m hoping for several million more, because I’ve loved every one—thanks to you T-town folks. Guys, you’re awesome. And generous, to boot—I think I had a stroke or something when I picked up my copy of this week’s Weekly Volcano and found my name printed next to “Best Visual Artist.” Holy moley. Thank you for the vote of confidence—you’re inspiring me to git to work!

Speaking of work, which I’m not quite ready to show you yet, evidence of the past two years has been on the front burner lately. Since I first came up with the concept for my Mt. Rainier book, I’ve covered a lot of miles in our fair state. And above all else, what I love about the Pacific Northwest are the contrasts. From oceans to mountains, rain forests to deserts, farm fields to bustling cities—it’s hard sometimes to remember that all of this is close to home.

So before I get back to a little picture-drawin’ next week, I’ve compiled a smattering of photos taken since my last anniversary post to illustrate what I’m talking about.

In two years I’ve amassed nearly thirty thousand digital photos of the Northwest—and that’s just of the relatively small hunk of territory I’ve managed to cover in that time.

Here’s to the next thirty thousand photos, and the next seventeen thousand five hundred twenty hours—I wonder what they’ll bring.

August 2nd, 2010

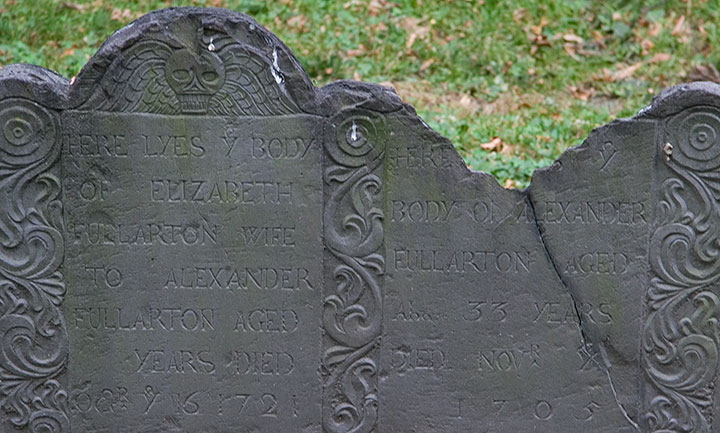

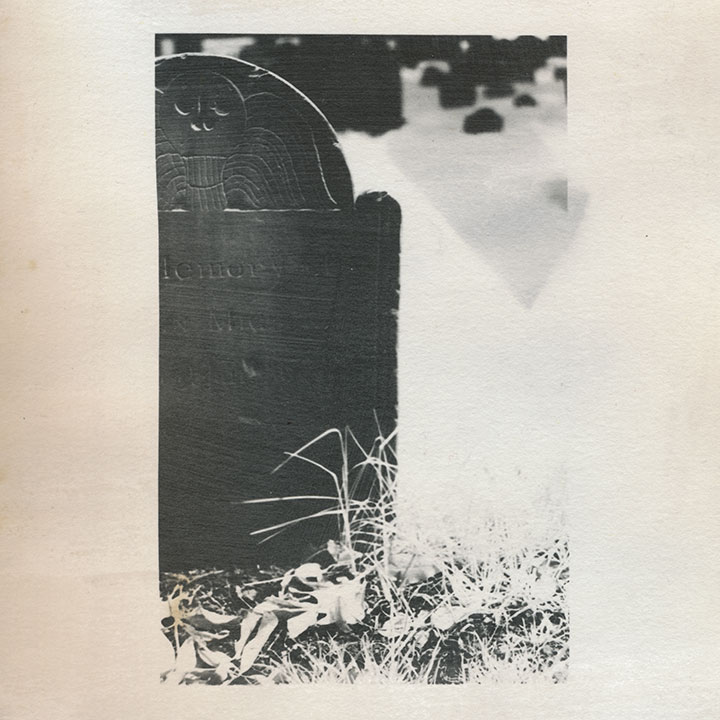

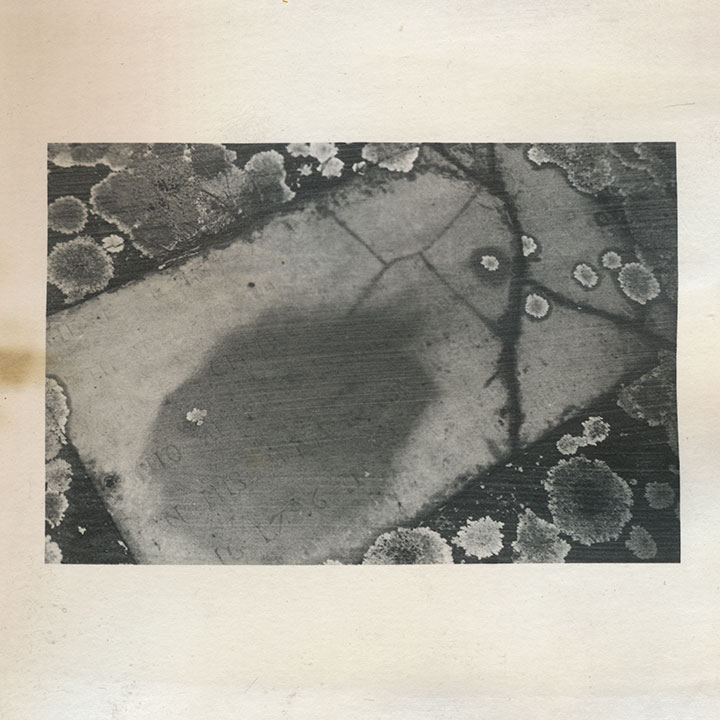

One of the things I used to do with Bampa is visit the colonial graveyards tucked away in every corner of New England. On this trip I only had time to visit a couple, so I picked my two favorites: the Old York Burial Ground in York, Maine;

and the Granary Burying Ground in Boston.

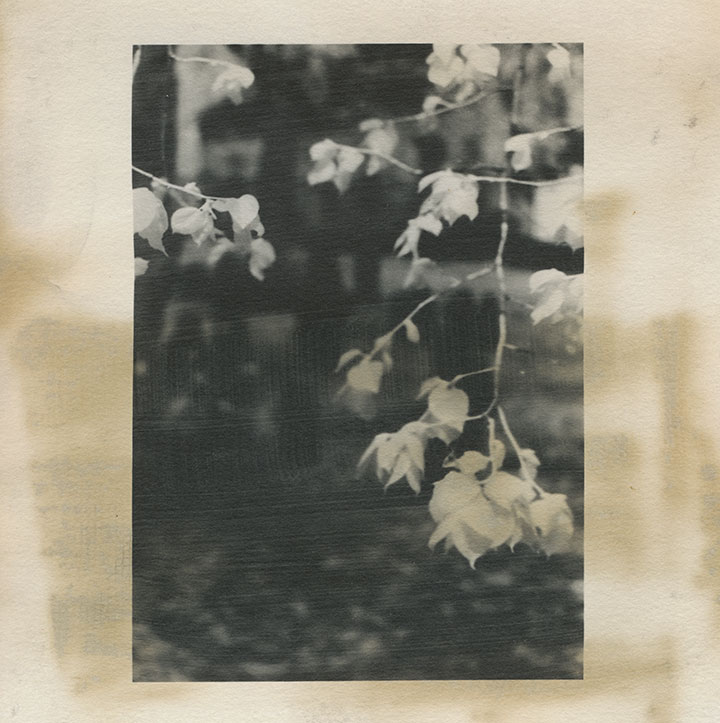

I’m quite a bit obsessed with these places; beyond my usual souvenir sketches and snapshots, these cemeteries keep popping in and out of my body of work. This is an excerpt from an artist book I made seven years ago. That’s not snow—it’s shot with infrared film, which behaves very differently from normal film when you do certain things with it. I used a dark red lens filter that blocked nearly all of the visible spectrum, so that the film was exposed mostly by ambient infrared radiation. The effect is that inanimate objects like stones read as deepest black,

and plants and flesh turn to bright white. Somehow I thought that particular quirk paired well with the subject matter—that living things behaved very differently than…well, dead ones.

Despite the near-constant crowds (in Boston, at least) and the challenge they present to photographing, each is an oasis, a tranquil island within the bustling town or city.

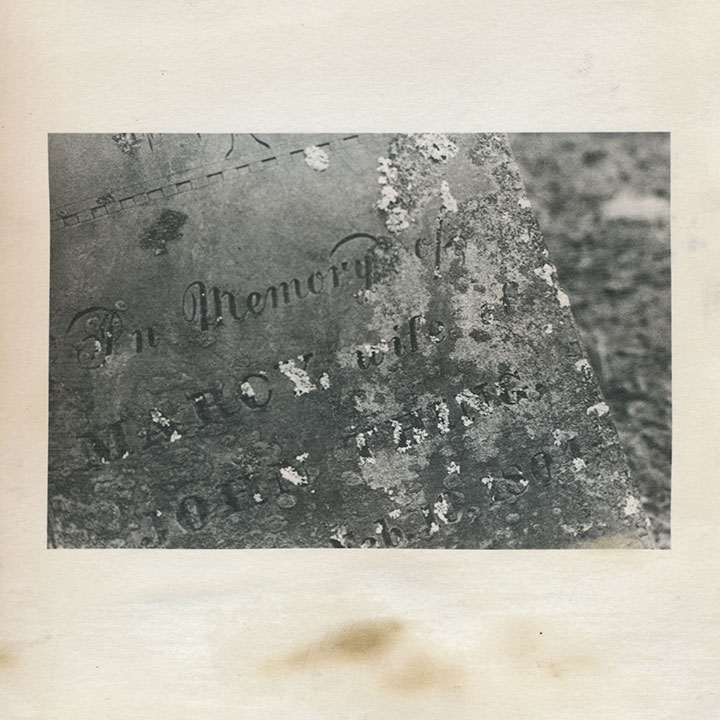

That’s not what draws me to them, though. Nor is it the haphazard scatter of wonky stones,

nor the romance of crumbling ruins.

(infrared film again)

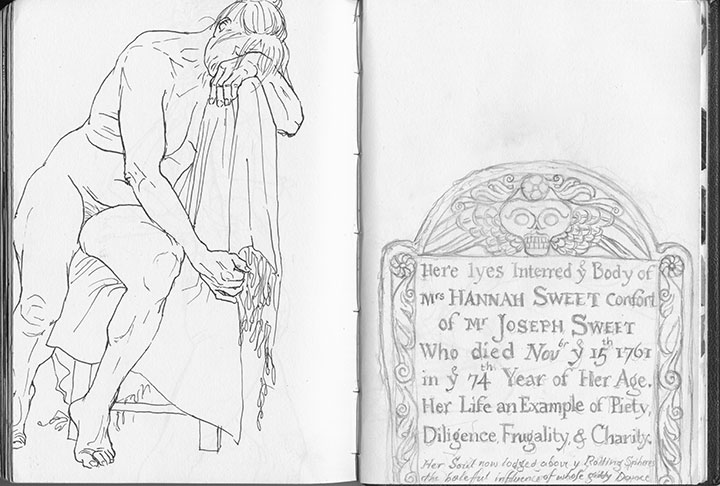

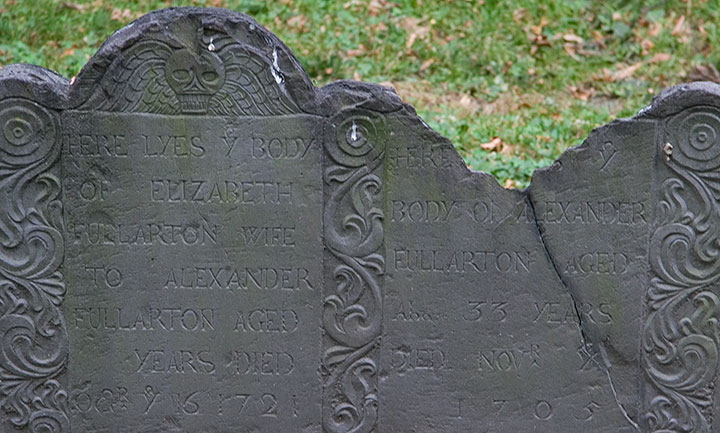

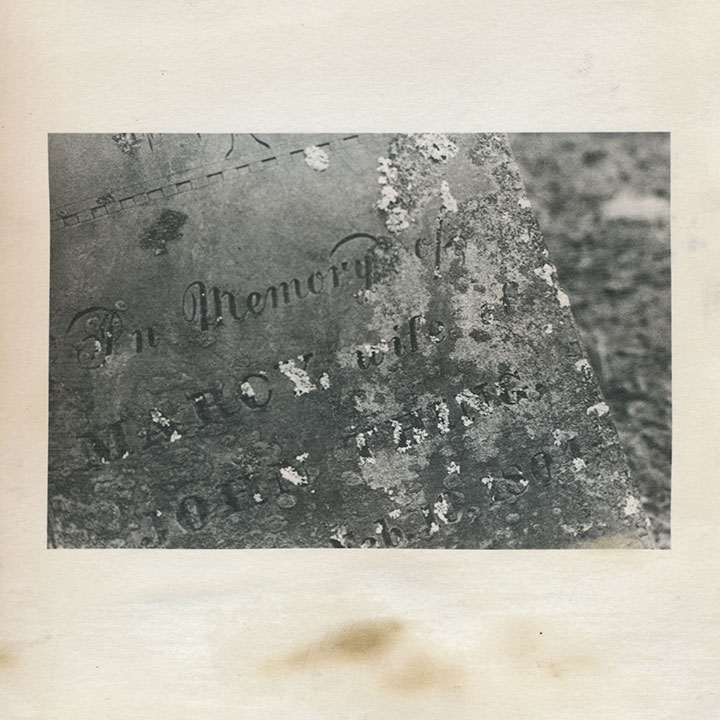

It’s that old gravestones are monumental (sorry) in the graphic design department. You can probably guess what my headstone might look like one day, because I’m completely fascinated with the design, the illustration, the typography displayed on colonial headstones. The “Death’s Head” or winged skull motif seems to be the most common,

with many variations within the theme—

Quadruple grave, dated 1666-1671, of children who lived only “dayes” or months apiece

from refined,

grave for a member of the Goose family, founders of the Mother Goose tradition

to folksy,

to somewhat disturbingly lifelike deathlike.

Another popular design is the “Winged Cherub,” which seems to be a more gentle alternative to the bones-n’-feathers motif.

The carvers seemed to take even more artistic license with this theme; I lost count of all the different angel designs.

Skulls and cherubs aside, just as fun for the modern visitor is the engraved text. Typophiles will love all the script faces and lettering conventions (my favorite, below, is a mention of “November” set with “br” as superscript above a larger “Nov”),

but I’m partial to the language—the poetic phrasings, the archaic spellings. Some excerpts, verbatim:

• “Here lyes interred ye body of Mrs. Hannah Sweet, confort of Mr. Joseph Sweet, who died Nov’br ye 15th 1761 in ye 74th year of her age.”

• “On His unfailing promises rely / and all the horrors of the Grave defy”

• “… Jotham Bush of Shrewƒbury, who departed this life with the Small-Pox”

• “In memory of Mrs. Elizabeth Hurd, amiable & virtuous confort of John Hurd, Esq.”

• “Farervell Vain World, I have Enough of thee / and now I’m Careles what thou Say’st of me”

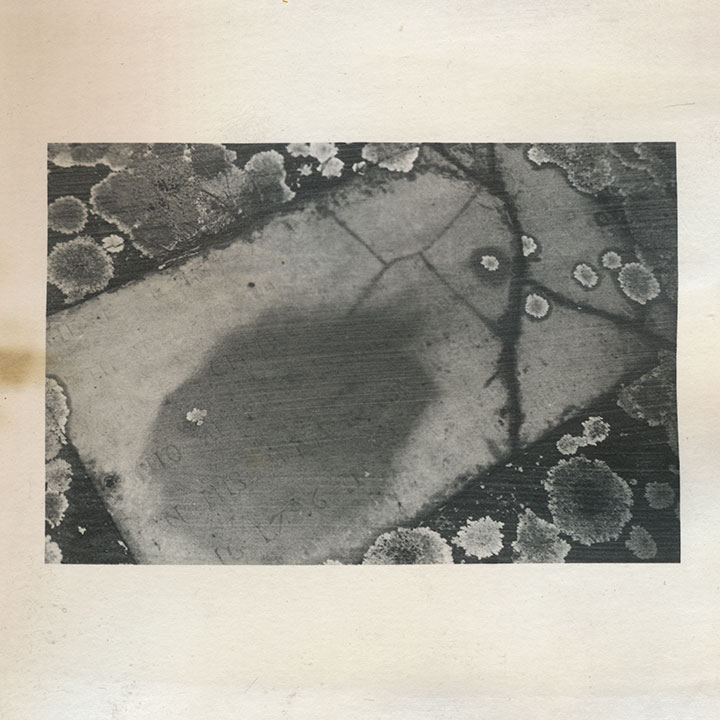

My little artist book has developed an unexpected conceptual element. I first coated the paper myself with liquid emulsion to make it light-sensitive (instead of using standard photo paper), then processed the images in a darkroom with the usual chemicals. By doing that, I was veering away from the traditional darkroom process, and adding some interesting variables, risks and imperfections into the mix. Most noticeably, the fixer reacted a little oddly with the emulsion/paper—a fact that irked me greatly at the time, since there was no way to know it had happened until the images were finished.

Over the years, however, the splotches have darkened, creating the illusion of old age and mirroring the weathering, decay and moss growth of the graves themselves.

So despite my perfectionist nature and my usual complex over making everything as archival as possible—I like the book so much better this way.

After all, it’s all the same in four hundred years anyway, isn’t it?

July 29th, 2010

At the end of a whirlwind trip that still hadn’t quite sunk in, I wanted a long, solo walk to clear my head before my flight home. So I got on the 8:57 Downeaster to Boston, and spent the remaining four hours before I had to get to the airport walking a familiar radius of old haunts.

Then it was back on the train again, off to catch my flight. I love the Blue Line because it doesn’t stop at “AIRPORT,” and because it’s my favorite metaphor for Boston. I don’t mind the traffic, or the grime, or the expense, or the often-lousy weather—because at the end of all of that is Wonderland.

July 25th, 2010

All this talk of stolen vacations, and all I had to do was wait another week. Well, maybe not for a vacation, per se, but certainly a change of scenery. My mother called to let me know that my grandfather, who lived in Exeter, NH, was entering hospice care. Before I knew it, I was on a plane back East. For the first time in my life, it felt like going away rather than going home, but my roots are here nonetheless. So between visits with Bampa, I took a Yankee trip down memory lane.

The parts of New England that trigger the most memories for me are the stone walls. Criss-crossing the woods and fields like seams, the walls are some of the oldest remnants of Colonial culture—demarcating property boundaries and connecting living New England with its past. And every time I go back, New Hampshire’s own Robert Frost recites in my head:

Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun,

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors’.

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows?

But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me~

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

July 17th, 2010

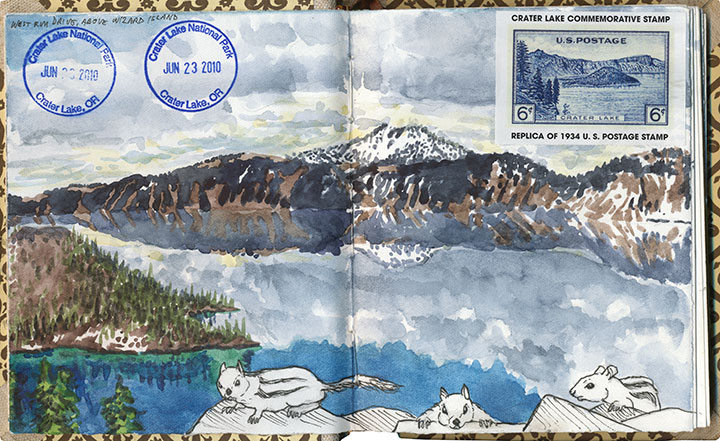

The second part of my little stolen holiday was a little more ambitious: a four-night camping trip with the Tailor in southern Oregon. It was just what the doctor ordered—the perfect prescription for recharging the soul.

We camped in the Rogue River National Forest, in a grove of hemlocks and blooming dogwoods, just downstream from this:

The Rogue is so beautiful that we could have spent the whole trip exploring its banks. Well, if we hadn’t had another destination in mind, that is:

Crater Lake National Park. One of the deepest, clearest lakes in the world, Crater Lake was formed 7,700 years ago by the collapse of Mt. Mazama, after an explosion more than forty times the size of the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens.

When a group of prospectors stumbled upon it in 1853, and thus became the first white folks to lay eyes on it, they named it Deep Blue Lake. Heh. You can tell they worked hard to come up with that one. Well, at least it’s descriptive.

And accurate. The lake is so impossibly blue because of its depth; when the sun’s rays refract upon hitting the water, red and green light are absorbed in the depths, while only the blue light (which has a shorter wavelength) reflects back to the surface. So the lake is blue even on a cloudy day—as you can see.

We were a week too early for the boat tours to open for the season, but we hiked down to the water anyway. The rangers like to say that the trail is “one mile down, ten miles back up” (it’s funny because it’s true. Oy.), but the experience is well worth the huffing and puffing. Next time I’ll bring bug spray, though. Note to self.

Did I mention that it’s blue? And deep? Maybe those prospectors were onto something.

The photo above doesn’t come close to doing it justice (none of my photos do), but the sheer depth and clarity of Crater Lake was mind-boggling. It’s impossible to tell how deep the rocks in the upper left corner of the photo are, but according to the topo map in front of me, it’s quite a ways down. Because there are no streams in or out of Crater Lake, there’s nothing to muddy or disturb the water—objects are visible nearly 150 feet down. Deep Blue indeed.

The thing that really got to me was the fact that the lake was both a bottomless pit and a perfectly-flat mirror, depending on which way you looked at it. That’s probably why this is my favorite photo of the trip—somehow the camera managed to look at things both ways.

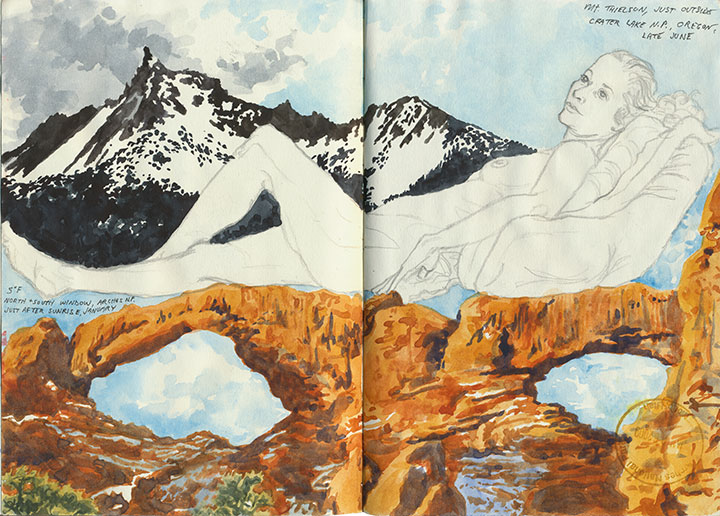

I think I must have been trying for the same kind of perspective with this drawing—and with far less success, I’m afraid. My brain broke when I tried to analyze the thing graphically. Ah, well. (The ground squirrels were fun, though.)

This one worked out a lot better—and it didn’t hurt that the figure and desert drawings were already there to help things along.

Speaking of deserts, we also saw a whole lot of barren landscapes to balance out all this snow and water. For one thing, we drove down and back on the eastern (the arid leeward) side of the Cascades. For another, there are places where all this ancient volcanic destruction still looks like it happened last year. This is the Pumice Desert, on the north side of the National Park.

And this is something else again. Now, I loved everything we’d seen at the Park, but my absolute favorite part of the trip was this place, which made for a side trip on the way home. This is just south of the Newberry Caldera, another collapsed volcano formed in precisely the same way as Crater Lake, but on a much smaller scale. A trail winds up and through the rock-pile hills—a landscape that seems plucked from the surface of the Moon.

If you step closer, however, you’ll see the light glinting off of each rock and pooling in every crevice. In full sunlight the entire hillside sparkles like a gigantic, blinding treasure hoard.

The rocks shine because they’re not rocks—they’re glass. This is obsidian, a natural glass formed when lava cools rapidly without crystallizing. Besides being gorgeous and just about the coolest thing ever, obsidian is extremely useful as a surgical tool. Obsidian scalpels can be sharpened to a near-microscopic edge (because of the not-forming-crystals thing), and the incisions they make produce narrower scars than steel scalpels do. Neat, huh? Anyway, obsidian flows of this size are quite rare, so if you get the chance to walk through one—take it.

I could have stayed all day with the obsidian (which, by the way, is called the Big Obsidian Flow, a name that gives Deep Blue Lake a run for its money), but we were still several hours from home (we figured we’d have to spend the first hour stepping carefully around all the ground squirrels that had appeared at our feet), and we still had one more stop to make:

Lava Butte, from which it was possible to see pretty much every darn volcano in Oregon, and even Mt. Adams in Washington. I won’t bore you with the 200 other photos I shot from up there, but let’s just say I was in suitable awe.

Oh, and for the record? All of these volcanoes are still active. How freaky is that? Or maybe it isn’t, and I just have volcanoes on the brain, but I think it’s freaky.

I lost count of all the volcanoes we spied, but the rest of the numbers were easy to tally:

Five glorious days.

Five breathtaking sunsets.

Five thousand smiles.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)