Blog

October 17th, 2009

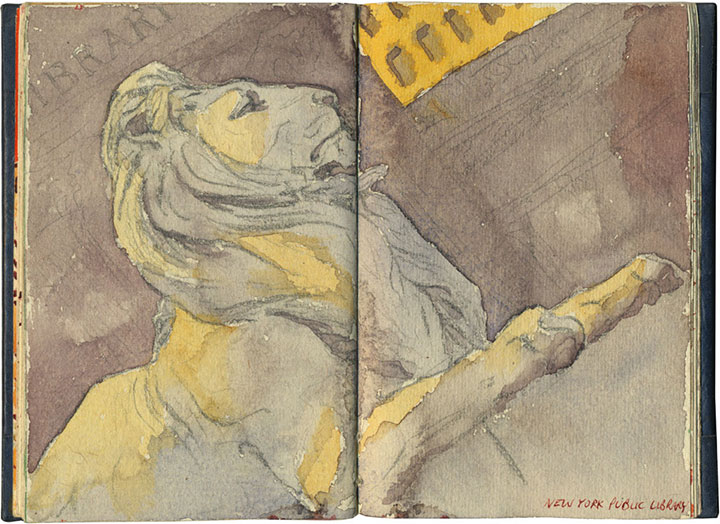

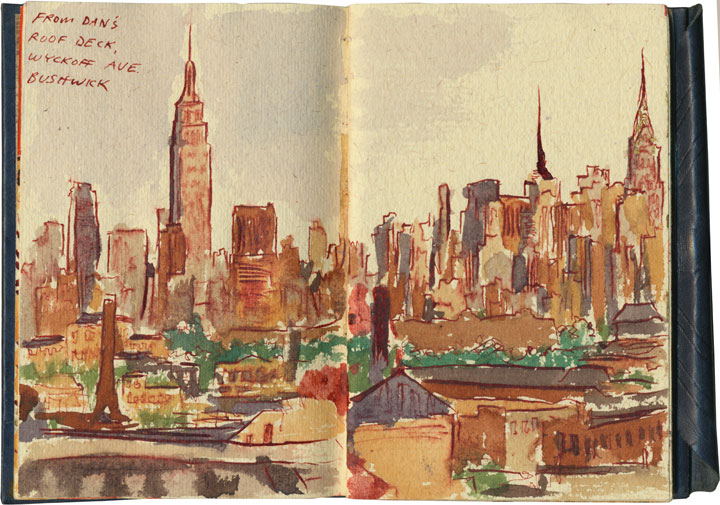

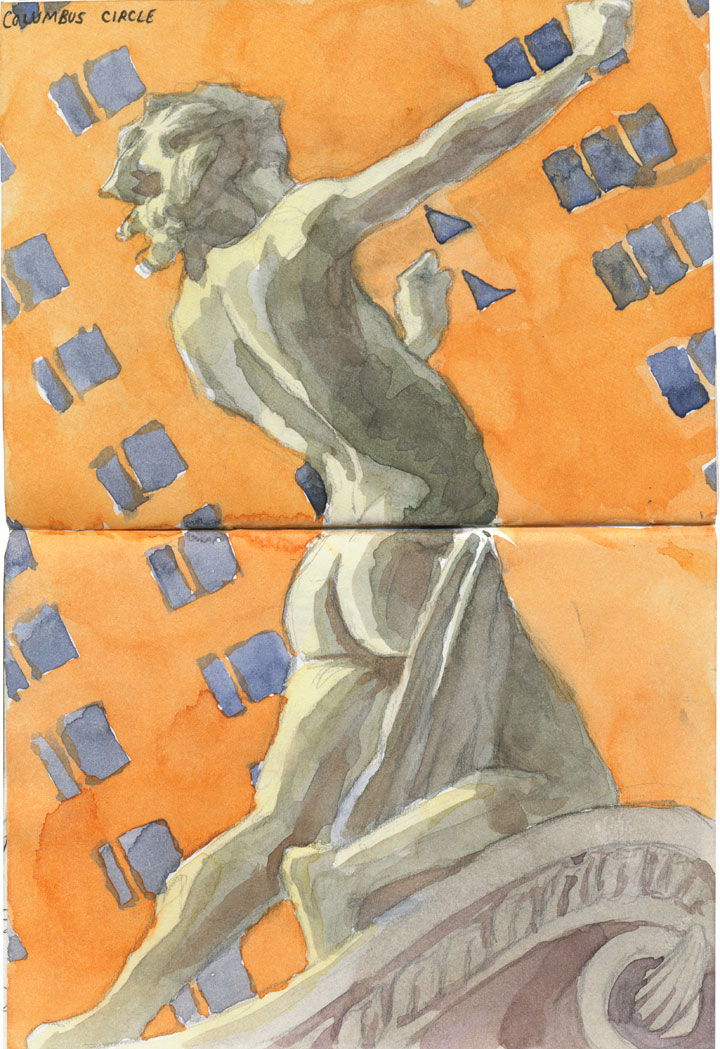

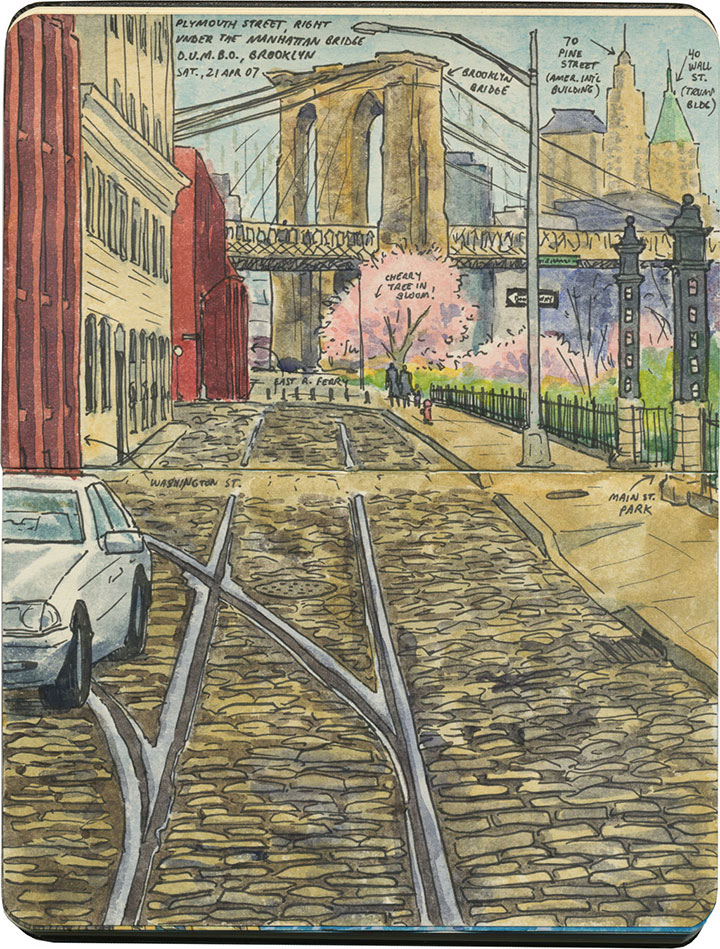

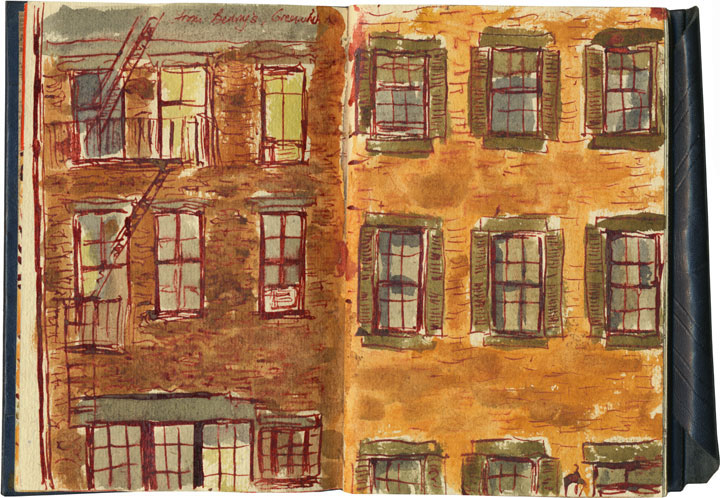

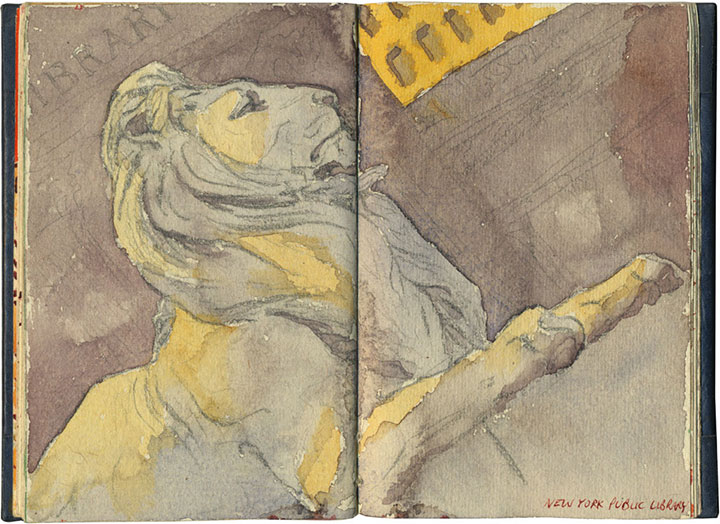

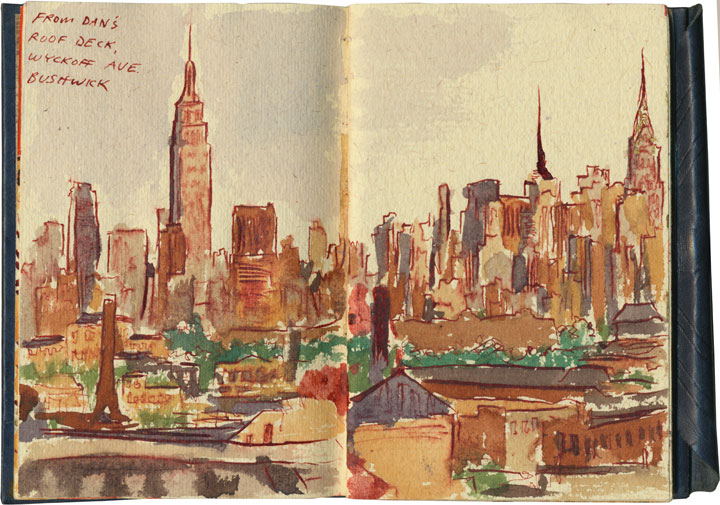

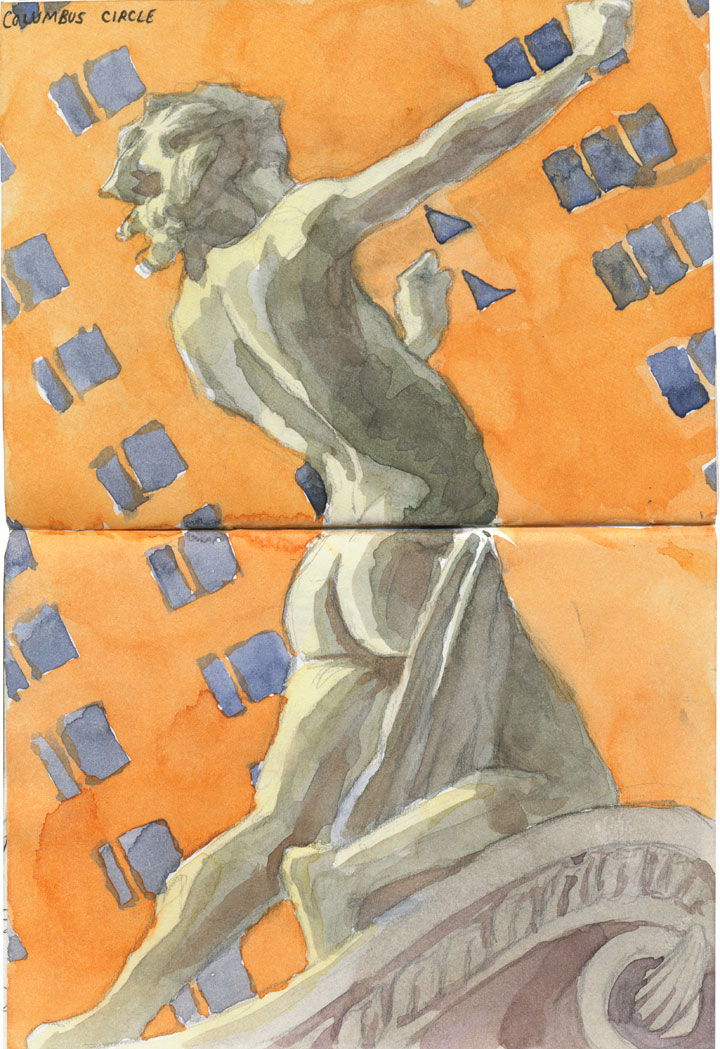

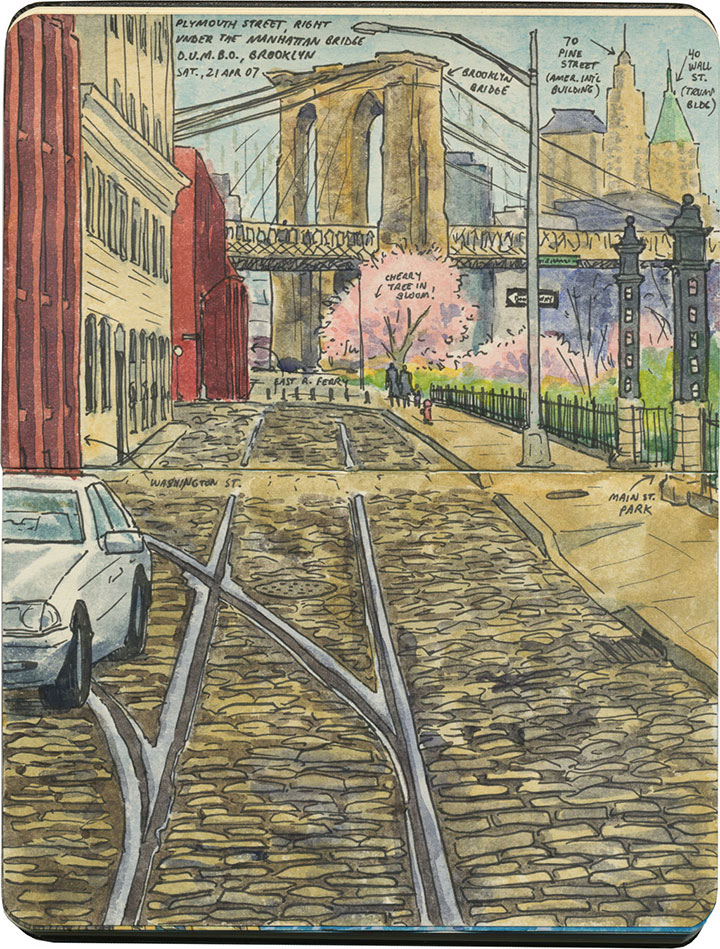

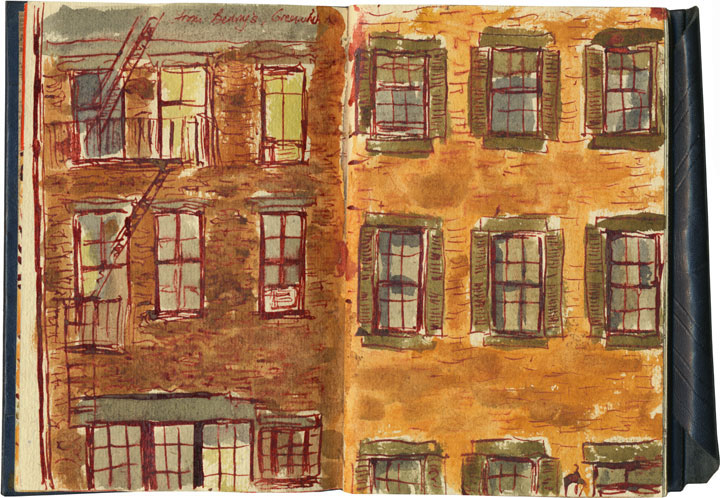

Last week I spent a few days in New York for the wedding of some dear friends.

I lost track long ago of just how many trips I’ve made there over the years, or how many months’ residence would equal the sum of all my days spent there (plenty).

My memories and souvenirs reflect this. I have whole sketchbooks devoted solely to Manhattan; boxes of still-good Metrocards and train schedules; miles of film negatives and a mental Rolodex stored to the brim with makeshift maps, habitual errand circuits and addresses of favorite haunts.

Every time I visit, it’s hard to string together a cohesive narrative of the adventure afterward.

Instead, my memories of New York are always a series of brief impressions; moments caught like fireflies in a jar.

Maybe it’s because each day finds me all over the map of the city, alternately in teeming crowds and completely alone;

or because I’d rather remember the best events and forget the worst (I’ve got a whole long list of those, too);

or maybe I owe it to the very nature of drawing and photography—whatever the reason, this trip was no different.

And every moment is another thread woven into a huge, neverending tapestry that tells the story of my very own, personal New York.

And for me, that’s the best thing about it.

September 25th, 2009

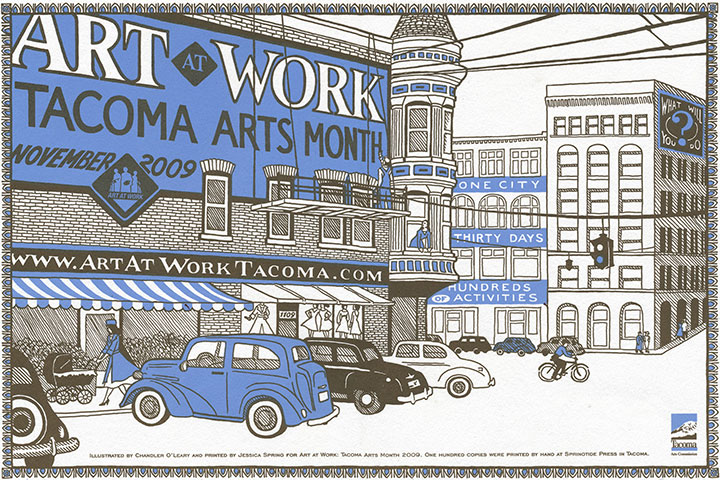

For the past several months, the buzz here in T-town has centered around the Luzon building on Pacific Avenue, a 119-year old structure that, depending on whom you ask, is either an architectural gem or a decaying eyesore. (As you can probably guess, I fall into the first category.) Above is an image of the Luzon in its infancy; this photo is printed from a turn-of-the-century glass plate negative found in Jessica Spring’s attic (and is part of her artist book, Parts Unknown). The thing about the Luzon that has made it such a sore spot around here is that it’s not just a living piece of history—at the time it was built, it was something of an engineering marvel. Co-designed by Daniel Burnham, who went on to design the Flatiron Building in New York and became one of the pioneers of modern multi-story structures, the Luzon was one of the first buildings in America to have steel columns. That makes it a direct ancestor—the great grandpappy, if you will—of the American skyscraper itself.

This is the sorry state of the Luzon today. Even though it is on the National Register of Historic Places, and is one of only two Burnham & Root buildings remaining on the West Coast, it has been allowed to decay, apparently beyond the point of no return. While each of many redevelopment schemes over several decades has fallen through, the building has become increasingly derelict. Now that the adjacent property—which provided structrual stability—is long gone, the Luzon is crumbling under its own weight. The City has even closed the surrounding streets in case of a collapse.

Oh, and there’s a tree growing out of it. I don’t think that was part of the original plan.

Well, whether it was a ploy to get around the Historic Register for a development scheme, or the powers that be just dragged their feet for too long (or some combination thereof), the detractors are finally getting their wish. The building is slated for demolition tomorrow morning. So now everyone (including me) has got the Luzon on the brain.

Last week the inimitable artist/cartoonist RR Anderson (who has a few choice words himself about the Luzon’s fate) challenged me to compete in his weekly sidewalk chalk contest, the Frost Park Chalk Challenge. I was looking for an outlet for my Luzon frustration, so I accepted. I grabbed a hunk of charcoal, a handful of communal Crayola chalk, and headed for a highly visible chunk of concrete wall to create a public altarpiece.

Photo by R.R. Anderson

My little Ascension doodle earned me a lot of comments from passers-by and the title of BEST ILLUSTRATOR IN THE UNIVERSE (OF TACOMA) for the week (thanks, guys!).

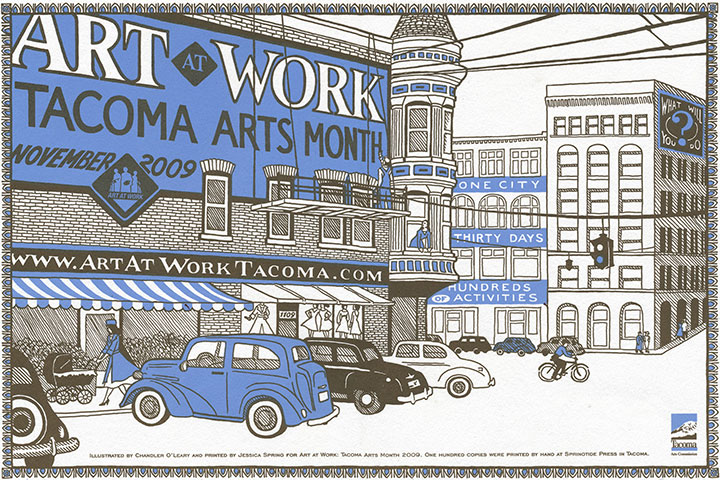

But sidewalk chalk isn’t exactly archival, and I wanted to make a somewhat more lasting statement. Here’s where letterpress comes in. Jessica and I were commissioned to design and print this year’s poster for Art At Work Month, hosted by the City. So since the theme for the overall Art At Work design this year is “ghost signs,” we decided the poster would be the perfect opportunity for a little cameo.

The original posters are letterpress printed in an edition of 100, and will be sold by the City in November, as part of the festivities. But a reproduction will also be inserted into every Art At Work brochure—over 10,000 of them. So come November Burnham’s gift to Tacoma will be long gone, but it’ll feel good to know that we did our part to make sure the Luzon is everywhere we turn—at least for a little while longer.

Edited to add: now that Art at Work month is over, you can now find the last few copies of the letterpress poster in the shop!

August 14th, 2009

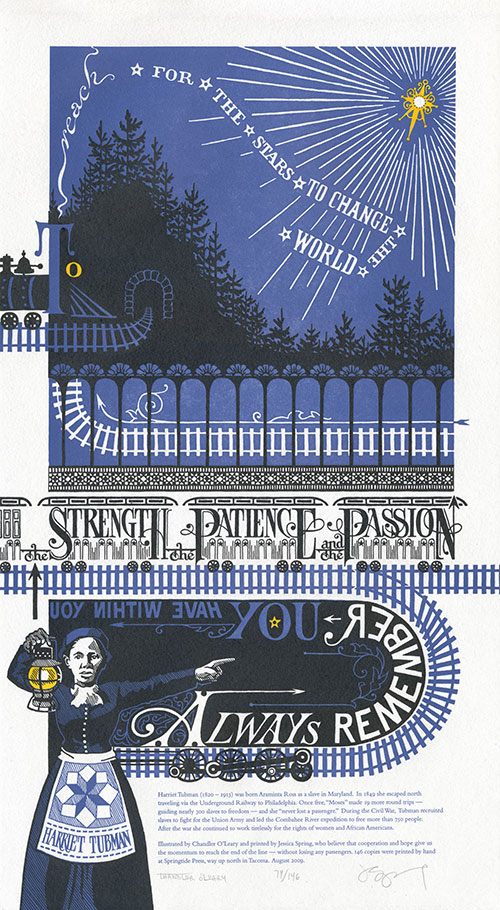

For nearly a year now, the Dead Feminists series has given us an outlet for both our aspirations and frustrations. For every social and political victory, there follows a reminder of how divided we are as a culture. We were so proud to see Victory Garden become a part of a nation-wide movement toward sustainability—but a movement and a majority are not the same thing. We are delighted whenever a customer tells us that Prop Cake is meant for a wedding gift—but are heartbroken by the reminder that for many people, the gesture can only be symbolic. Yet through it all we remain optimistic that art can make a difference—that a bright future is out there, somewhere, and that we can help find the way to it.

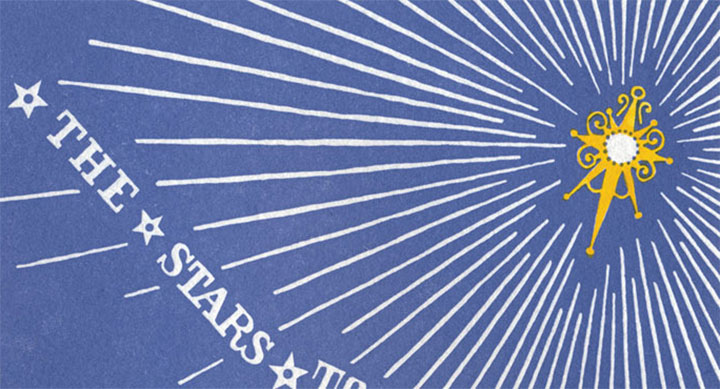

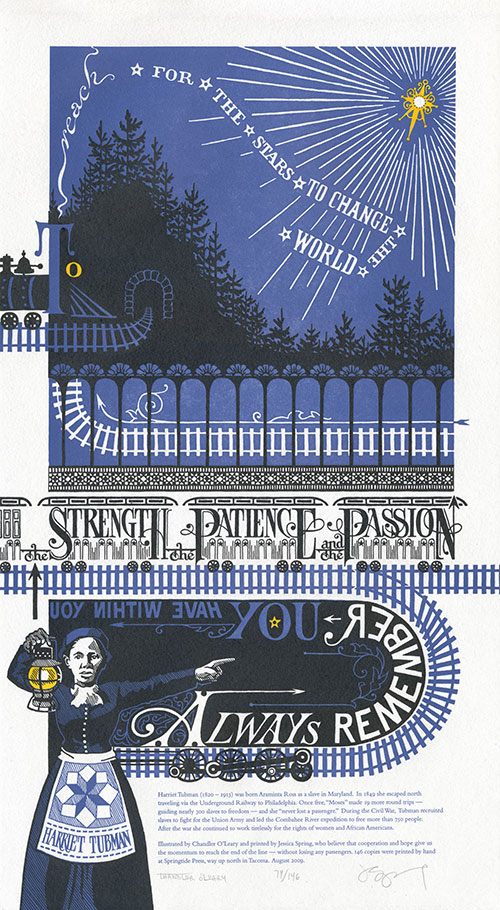

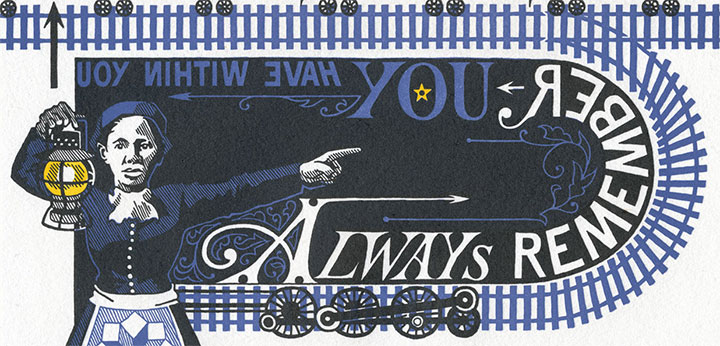

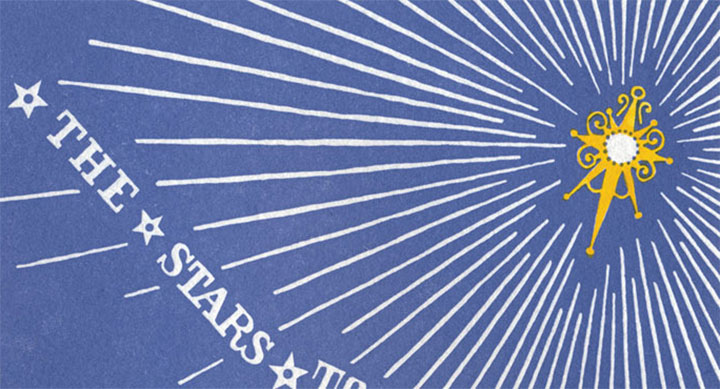

Always remember you have within you the strength, the patience and the passion to reach for the stars to change the world.

— Harriet Tubman

This is why we chose Harriet Tubman for our latest piece. There are so many pressing issues vying for our attention—war, the economy, healthcare, the environment, transit, equality, etc.—that we couldn’t choose just one. So we decided to focus on the journey itself. For all the ground we’ve gained in our country’s short history, we have a long, long way to go—and the only way we’ll get there is together. Harriet Tubman knew that when she fought for freedom and civil rights, and she devoted her entire life to the idea.

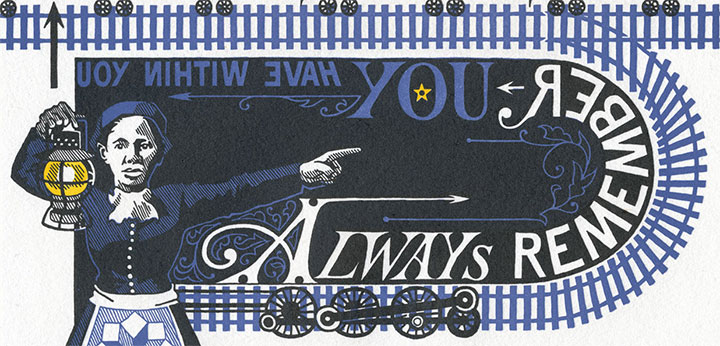

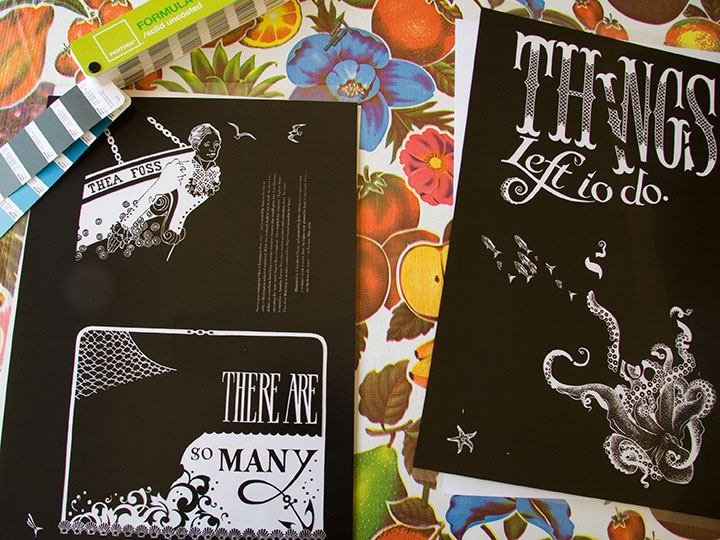

So here, submitted for your approval, is End of the Line. As always, everything—from the illustrated lettering to the letterpress printing—is done completely by hand. This time, though, we’re asking you to flex your reading muscles a bit: to symbolize the difficult journey faced by anyone with a great task, we made it somewhat of a challenge to read.

Don’t worry, though—Harriet is there to guide you. Just follow her lantern, and you’ll find the right path. If you lose your way, just look for the Drinkin’ Gourd.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

End of the Line: No. 5 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 146

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press and hand-colored with watercolor. Each piece is printed on archival, 100% rag, recycled paper, and signed by both artists.

Colophon:

Harriet Tubman (1820 – 1913) was born Araminta Ross as a slave in Maryland. In 1849 she escaped north traveling via the Underground Railway to Philadelphia. Once free, “Moses” made 19 more round trips—guiding nearly 300 slaves to freedom—and she “never lost a passenger.” During the Civil War, Tubman recruited slaves to fight for the Union Army and led the Combahee River expedition to free more than 750 people. After the war she continued to work tirelessly for the rights of women and African Americans.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, who believe that cooperation and hope give us the momentum to reach the end of the line—without losing any passengers.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

August 6th, 2009

A year ago today our bright yellow moving truck pulled into Tacoma and turned the corner onto a new home, a new career, a new life. Here I am, 365 days later, and I’m still just as excited as on day one. To everyone in T-Town (and Seattle, and Portland, and everywhere in between!) who has welcomed me as one of your own: thank you, with everything I have.

I tend to be a list-maker, constantly looking ahead to what is yet to be done. And as I sifted through the thousands of photos I took over the past year, trying to narrow them down to a few favorites, a whole new to-do list emerged. Despite my best, most frantic efforts, I’ve barely scratched the surface of this new home of mine.

So I’ve got my work cut out for me. Washington, I’d like to get to know you a little better.

July 20th, 2009

I serve on the board of the Book Arts Guild, a group that started as little gathering place for like-minded souls in the Pacific Northwest. It has since spiraled outward to include hundreds of members in all corners of the art form and the country—and suddenly thirty years have gone by. On Saturday fifty or so of us got together to celebrate the occasion at the Stern & Faye “Printing Farm” in the Skagit Valley.

We couldn’t have asked for a better day—I could have stayed all afternoon in the orchard, chatting with kindred spirits.

I had heard so much about the studio, however—so while most of the group was drawing for prizes in the loft,

I wandered downstairs to do a bit of exploring.

This is Jules Remedios Faye, “Proprietrix” of the Farm. She and her husband, Chris Stern, moved to the Skagit Valley fourteen years ago and turned an old barn into a letterpress printer’s dream.

The space is at once cozy and seemingly never-ending,

serving as both a working studio and a living relic.

The place is chock-a-block with tools, type and ephemera, and functions as a type foundry as well—one of a small and dwindling number remaining in the U.S. these days.

After Chris passed away in 2006, Jules was forced to scale back the studio a bit to continue managing it alone. The barn is still very much alive, though—the walls are festooned with prints, and evidence of well-loved and continuing use is all around. It feels like their space, not just hers.

His presence is everywhere—a fitting memorial.

The Printing Farm was the absolute best-possible place to celebrate the anniversary of the Book Arts Guild. It served as a touching reminder that no matter how far into the past our roots go, no matter who has gone before us or what new trends have appeared, we’re still here—still breathing, still practicing, still creating.

After all, that’s what we’re here for.

July 13th, 2009

First, invite your family down for the day. Squeeze out some fresh lemonade;

and fry up a free-range chicken.

Then mix up some cream, sugar, and fresh berries (plus just a pinch of that lemon juice to bring out the flavor);

pack ice and salt around it;

and start crankin’.

Let everyone pitch in—the longer you churn, the harder it’ll get.

Finally, when even teamwork won’t turn that handle, you’re ready.

And hey, presto—

summer in a bowl.

If all that ice cream gives you a chill, just head for the hot shop;

gather around the fire;

and bask in the perfect day you made.

May 16th, 2009

When it comes to letterpress printing, process is everything. And since that process is not always evident in the final product, I thought I’d share the technical aspects of the Dead Feminists series. Now, as I said in the last post, letterpress printing is traditionally done using metal or wooden type—or in the case of the photo above, relief images cut into type-high (.918 inches in the US and UK, in case you wondered) blocks. What Jessica and I have been doing, however, ain’t your grandpa’s letterpress. Thanks to a fairly new technology called photopolymer, we’re able to create our own relief plates right in the studio, without having to carve a block by hand or etch a plate with nasty chemicals. Photopolymer has also created a bridge between the traditional print shop and the modern digital world—as you’ll see in a moment. As far as the Dead Feminists go, Jessica and I still have both feet firmly planted in the traditional world—we just dip a toe into the digital realm now and again. Here, let me explain.

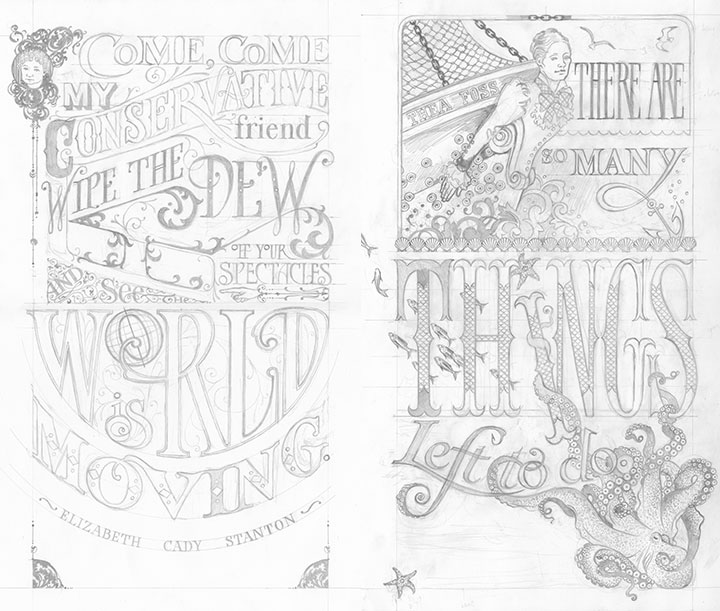

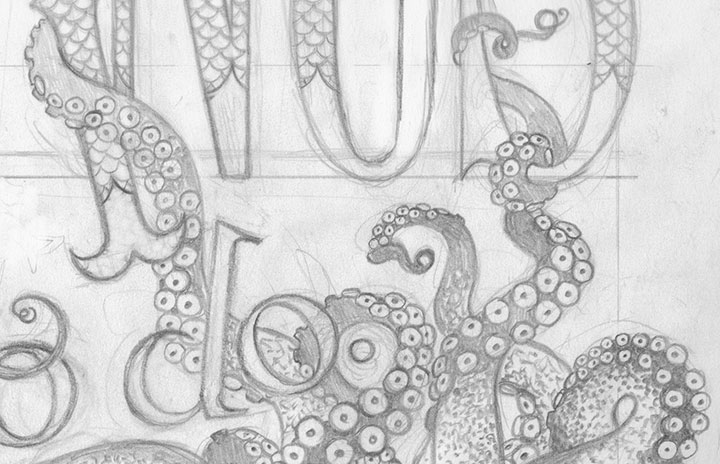

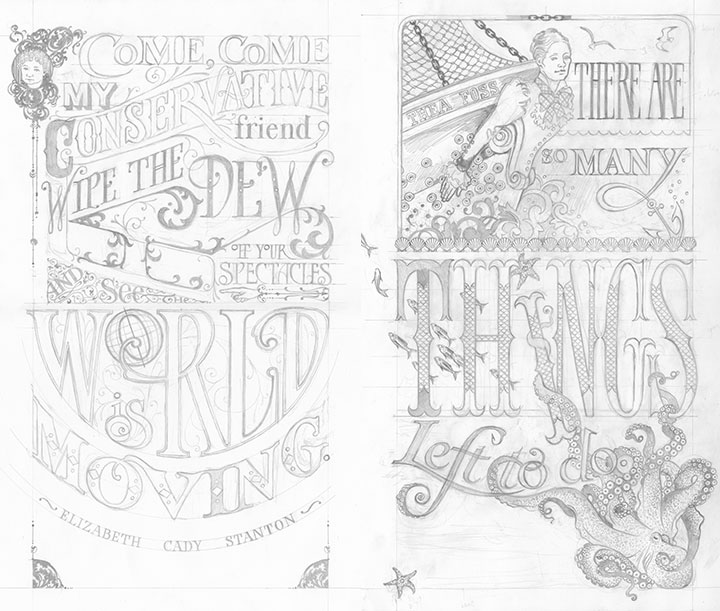

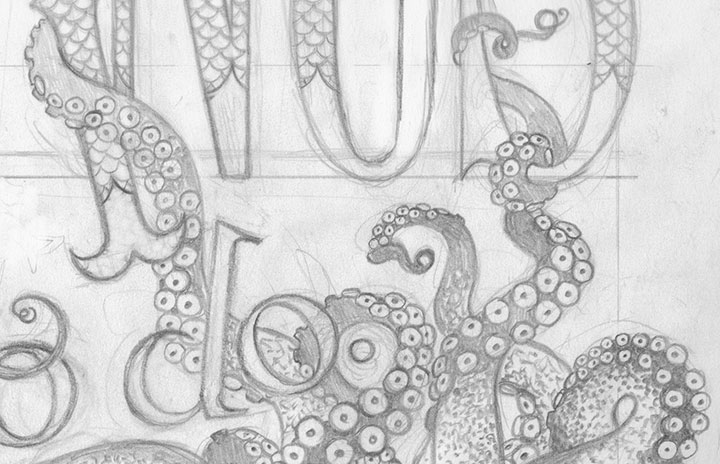

This is how it begins for each print: a pencil drawing, at full size. This is the stage where I not only design and illustrate the piece, but also start thinking about color choices: what the colors will be, what element will be which color, where the colors will overlap, how to make things work logistically. Now, this pencil layout isn’t enough to make a plate; for the photopolymer process to work properly, I have to translate the sketch into a solid black-and-white ink drawing.

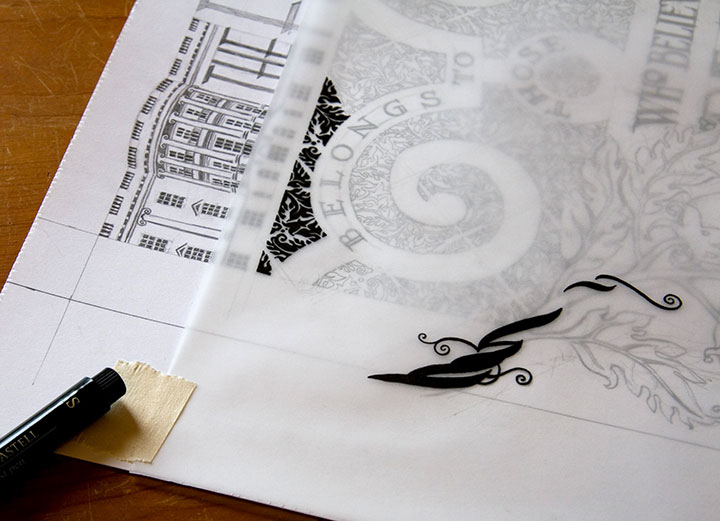

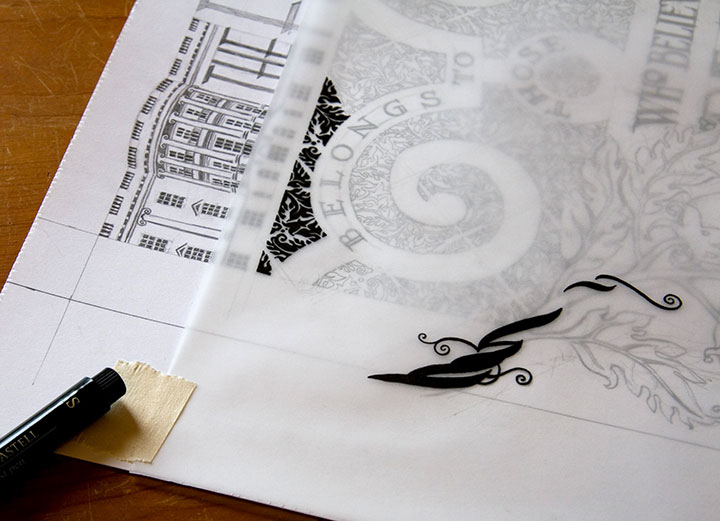

After everything is pencilled in, I lay a sheet of vellum over the drawing and trace everything in ink.

Since each broadside is printed in two colors, each color means a separate run through the press. So as a result, I had to trace each color separately—being careful to stay as true as possible to the original drawing, since the colors had to line up exactly on press. If you were to line these two color separations up, on top of one another, you’d see how the colors will interact in the final piece.

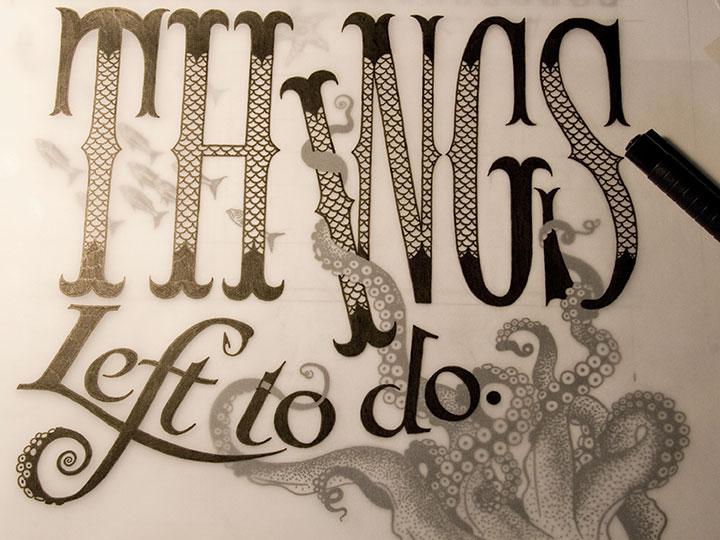

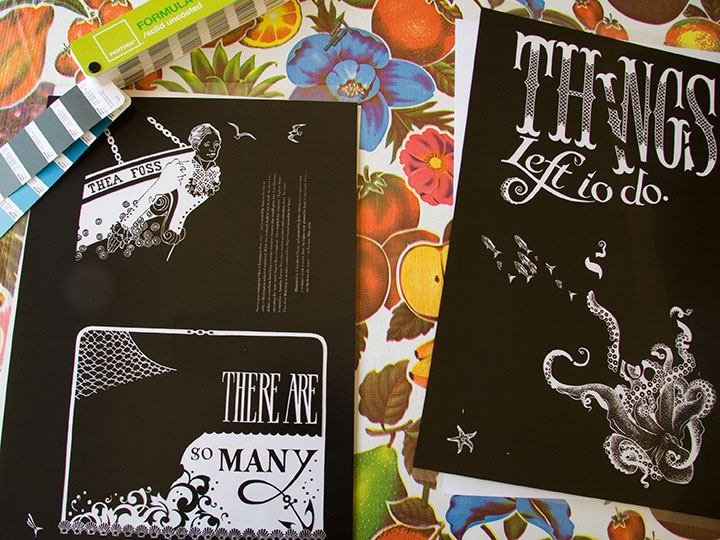

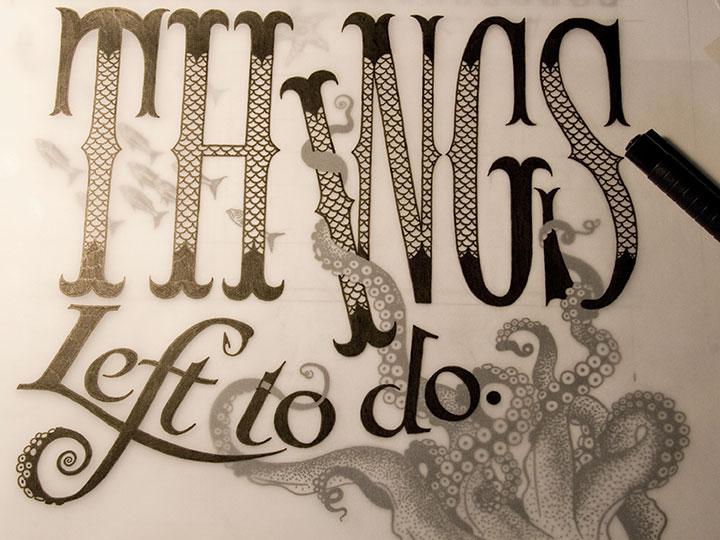

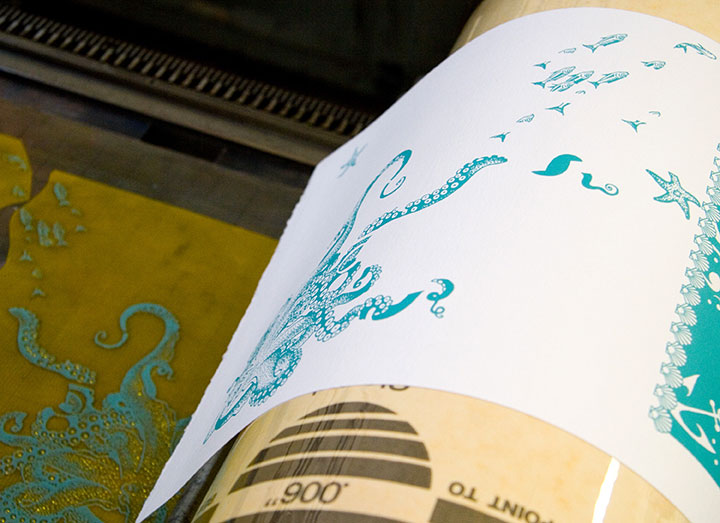

Here’s what I mean. You can see the separation that will become the grey color in Tugboat Thea here, laid directly over the inked octopus below. This is definitely the old-fashioned way of doing things; there are plenty of digital methods of color separation. I guess I just prefer the physical connection between the pen and the hand—even despite the greater risk of screw-ups (as you can see if you look closely at the word “to” above).

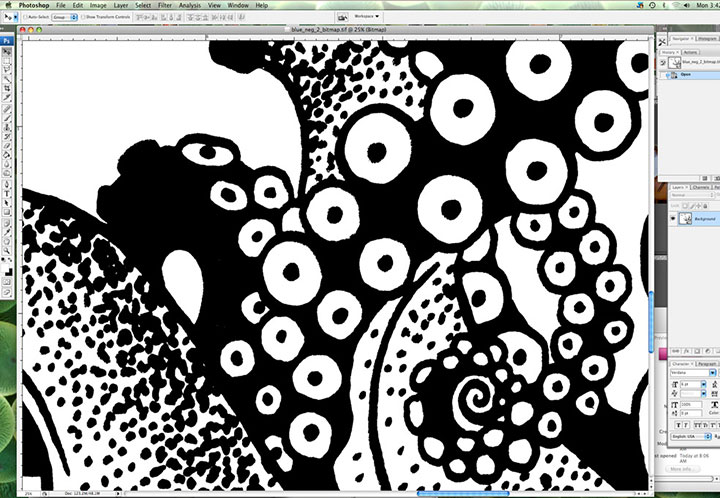

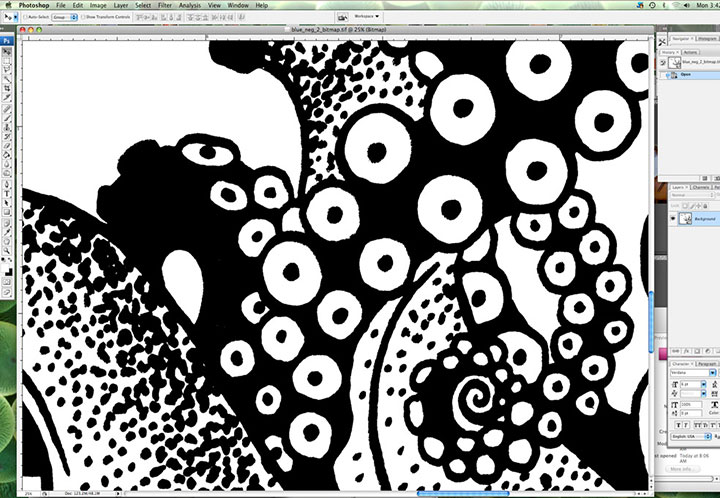

Here’s where I dip that toe into digital waters. Once I’m finished inking, I scan the finished line drawings at a super-high resolution and load them into Photoshop. This is where I clean up any mistakes (ahem) and convert the drawings into bitmap (pure black and white, with no grey) files. Jessica sends me her written colophon, and I set the text digitally. Then I export everything to the proper file type, and send the files to a local service bureau to have film negatives made. So now we’ve gone from analog to digital and back again.

Here are the negatives for Tugboat Thea; grey separation on the top half of each one, teal on the bottom. As you can see, there aren’t any right angles in the bottom half (octopus) of the teal separation, so if you look closely you can see the little tick marks I added (above and to the right of the starfish) to aid with color registration. Those marks line up with a grid etched on the metal base we use to lock up the plates on press; once we had the plates exactly where we wanted them, I simply shaved those little tick marks off with an Xacto knife, so they’d no longer print. Real slick.

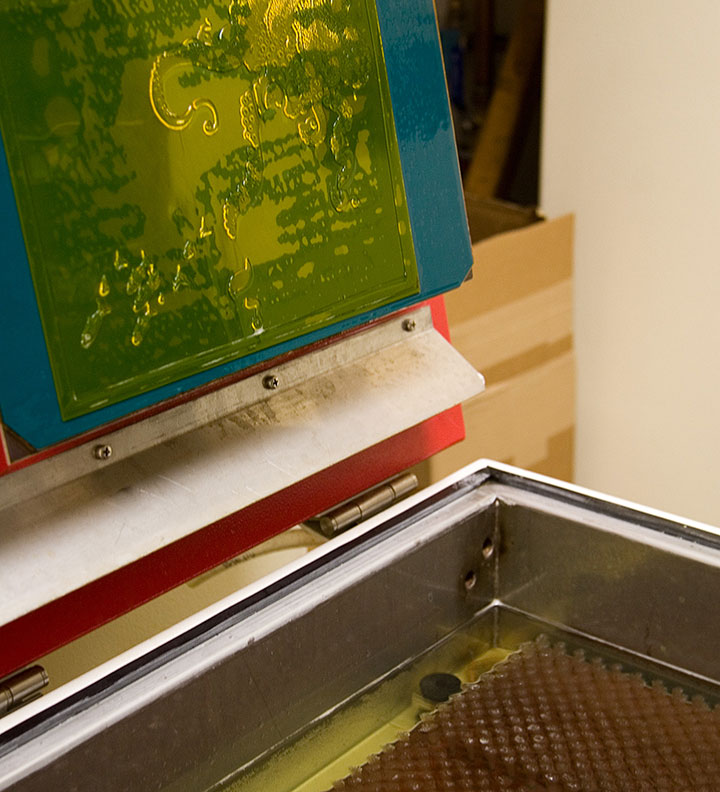

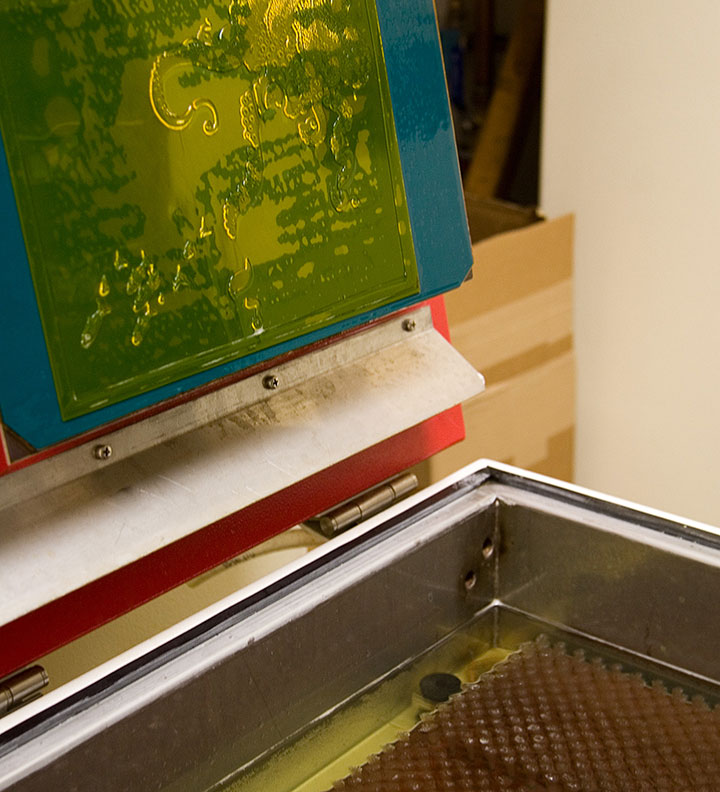

Anyway, photopolymer is a light-sensitive plastic that works just like making a contact exposure in a darkroom does. First I take a negative, place it face-down on an unexposed plate, and load both pieces onto the exposure tray of Jessica’s platemaker (which looks remarkably like an Easy-Bake Oven).

The negative is held flush with the plate by a layer of plastic and a vacuum system; the plate is exposed with UV light (some DIY enthusiasts also accomplish this using glass and a bright, sunny day, but photopolymer is awfully expensive to use in sketchy experiments in the cloudy Northwest).

Next I place the exposed plate in the wash-out unit, where it is scrubbed gently with soft bristle brushes in a tank of cool water. Everything that is exposed is hardened enough to resist scrubbing, while everything else dissolves away. (And turns the water a sickly shade of yellow. Mmmm….plastic byproducts. Still, it’s less toxic than many other printmaking techniques.)

What we’re left with is a raised plate ideal for relief printing. The real benefit of photopolymer is that it can reproduce nearly any image, and can hold an incredible amount of detail. I can transfer my drawings directly to the plate, without adding the laborious step of carving the image into wood or linoleum (backwards!), or etching copper with acid, for example. It’s not exactly an economical option for letterpress printing, but the results can be exquisite, and the possibilities are nearly endless.

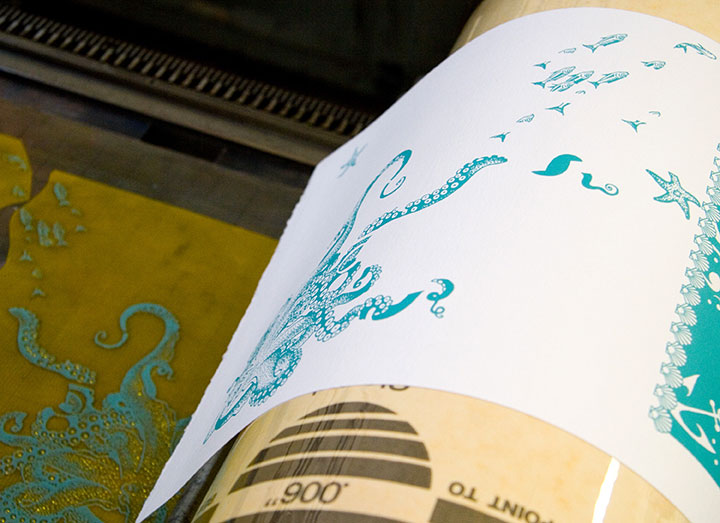

Here’s our new octopus plate on press, all inked up and ready to print—it’s stuck to that gridded base with removable adhesive. The thickness of the plate and base together add up to exactly .918 inches. Ah, precision feels good.

And here’s how it looks on paper.

Here you can see the registration between the colors. This is the hard part—I’m sure that despite my best separation efforts and useful tick marks, Jessica is ready to tear her hair out whenever she sees what insane registration issues I’ve thrown at her this time. She’s not a master printer for nothing, though—tiny, 9-point colophon type? No problem! Large, solid color blocks? Bring ’em on! Exacting registration with no margin of error? Sigh. Just get those plates locked up, will you?

Actually printing these broadsides is where all our careful planning and preparation goes right out the window. We can sketch and plot as much as we like, but many of our artistic decisions end up being made on the fly, right on press. Here Jessica is mixing ink for Prop Cake, according to some choices I suggested in our handy-dandy color recipe book.

You can see our original draw-down (color test) in the upper left corner. So far, so good.

The orange turned out exactly as we’d hoped, but when we started printing the pink separation, we hated the result. What looked so good in the draw-down lost all its contrast in the print. It was awful, trust me.

So Jessica changed the color right on press, until we were happy with it.

Here’s the finished product, all lined up in the drying rack.

If lining up the color areas is the hardest part of printing, keeping an eye on the ink consistency was probably the most fiddly. We’re using a very unusual paper for the series—one made from recycled clothing—that is extremely “thirsty.” Not only are there inconsistencies in the paper that can throw off the overall quality of color; but we had to add ink to the press after every fourth or fifth print. As you can see, this is a pretty organic process—lots of variables, small corrections and compromises along the way. (And a whole lot of cursing and starting over.)

All of this is par for the course for a letterpress project—it’s an exacting, sometimes frustrating process, but that’s what I love about it. And the finished product … well, it’s like nothing else. Ah, letterpress, how I love thee.

Now if only it didn’t require several metric tons worth of equipment…

May 14th, 2009

Holy cannoli, everyone! I’ve only just now come up for air—I’ve been buried under invoices, subscription forms, kraft mailers, and email print-outs, and Thea’s face is repeated all around me as reserved copies are spread all over the studio. Since I posted her here on Tuesday night the orders have just poured in, and over three-quarters of the edition is spoken for already. And Prop Cake is disappearing fast, too; we’re down to our last handful. Wow—just…wow. Thank you all so, so much.

Since Thea and her fellow Dead Feminists have left T-Town to be shipped all over the country (and to lovely Canada, France, Switzerland and the UK, too!), I thought it appropriate to share some of the things Jessica and I talked about at TAM the other day with a wider audience. Now, normally my paralyzing fear slight nervousness while speaking to a crowd manifests itself by wiping my memory clean immediately after I give a talk. It’s a very annoying thing, not being able to remember what you just said, but it happens all the time. I guess I’m fortunate that my phobias don’t show up as a quavering voice or profuse sweating (so nobody ever believes me when I say I get stage fright), but selective amnesia isn’t much of a fair trade for fake confidence! But this time, weirdly, it didn’t happen—I remember almost everything, and I think it’s because I wasn’t alone. (Jessica, I reckon that means you’re doomed to be my speaking partner from now on!) So to make sure my memory stays put, I’m setting it down here for the record. (By the way, since there’s rather a lot to say on the subject, I’ve decided to break it into two posts.)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

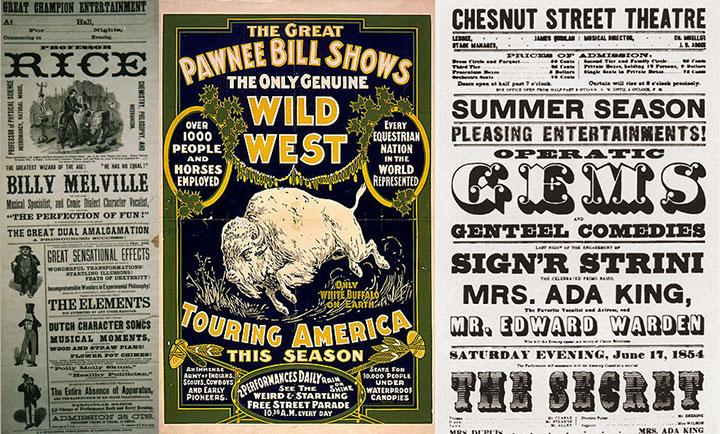

Before I get into the technical details behind our series, I should probably share a little background information on letterpress and the art of the broadside. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the process, letterpress printing refers to a type of relief printing, where pressure is applied to a piece of paper placed over a raised form that is covered with a thin layer of ink. This pressure transfers the inked image onto the paper, and can be repeated to create a batch, or edition, of prints. The form can be a carved block of wood or linoleum; a raised plate made of magnesium, photopolymer (plastic) or other materials; or as the term letterpress implies, movable type made from metal or wood.

The innovation of printing words from individual letter blocks that can be rearranged and reused was actually invented by the ancient Chinese (seriously, what wasn’t originally invented in China? We owe those folks a whole heap), but the process that evolved into modern letterpress was most famously perfected over 500 years ago by Johann Gutenberg, of Gutenberg Bible fame. By the first half of the twentieth century, when more modern commercial printing came along, it was still common for printers to perfect their layouts using movable type and relief-cut images on a proof press (such as Jessica’s Vandercook below). They’d then use the resulting print to make more sophisticated plates for their more efficient and advanced commercial presses.

Jessica printing “Prop Cake” on her Vandercook Universal One press

As commercial printing became more streamlined, the cylinder and platen proof presses (see photo above) fell out of vogue, and eventually were no longer manufactured. Artists quickly saw their potential, however, and have adopted letterpress printing as an art form—using, refurbishing and maintaining this antique equipment to create original works of art.

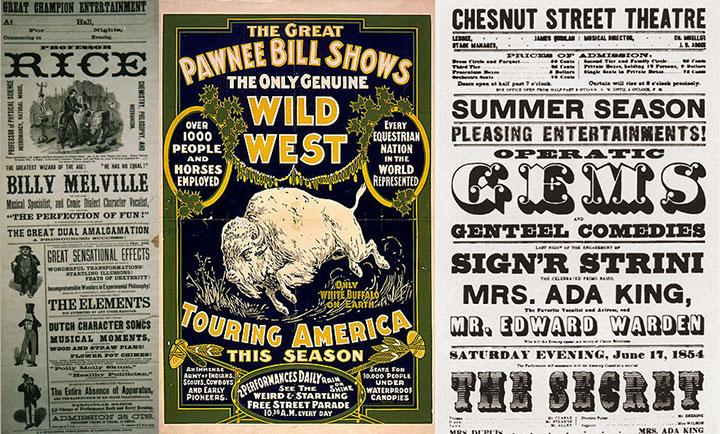

Hand-in-hand with letterpress printing, the art of the broadside has also survived and evolved into a modern format. The term broadside means any single sheet used to convey information, often of a political kind—the great-grandpappy of the modern poster. While today the words broadside and poster are sometimes used interchangeably, the broadside has remained a favorite of the letterpress community because of its emphasis on typography and content (hey, we need an excuse to use all that gorgeous metal type!).

Jessica and I had this history in mind when we began the Dead Feminists series. As I said before, we never dreamed of starting down the path we’re on now; we just wanted to make a political and artistic contribution to the election. And to pay homage to the history of the broadside and the era in which each of our feminists lived, I designed each piece with historic broadsides and posters in mind. And to keep the series consistent, Jessica and I came up with a few rules of engagement:

1. Each poster has to feature a quote by a feminist. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a woman, but there are already plenty of posters highlighting the words of dudes, so we figured that one was covered already.

2. Said feminist must be deceased. (Hence the name.) You’d be surprised how many challenges that’s created for us.

3. Each quote is tied into a current sociopolitical issue or event. This is usually Jessica’s job, as she’s got a particular knack for finding relevant quotes.

4. The whole piece (except the colophon at the bottom, of course) is hand-drawn.

5. We try to stay away from well-worn tropes like “women can do anything men can do!” in favor of broader topics and concepts.

Who knows how long people will be interested in these things, or how many broadsides there’ll be in the series—all we can say is that we’re grateful for the response people have had, and we’re having way too much fun to quit now. The fun of art-making and the joy of the public response aside, the best part of creating this series has been exploring the lives and work of so many inspirational people. “Feminism” has become somewhat of a dirty word these days—mostly because of misconceptions. To us it’s a positive thing, and creating this series is our way of celebrating those who championed far more than just gender equality. Besides, we’d like to make our own contribution to our social history—and using the “power of the press” in the literal sense is the best way we know how.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Coming in part two: the nitty gritty details behind our process.

May 12th, 2009

Well, here she be. (Or should I say, Thar she blows?)

At long last, Thea is here, barnacles and all. Jessica and I unveiled her at our Pressing Matters talk at the Tacoma Art Museum this morning. I have to say, I was nervous that with the weekday morning time slot, we’d be hoist on our own petard for the big debut. Since 10:30 on a Tuesday isn’t exactly an hour available to everybody, we were afraid we’d be lecturing a bunch of empty chairs. Boy were we wrong. Many thanks to all of you who skipped out on work, took a long (and very early) lunch, or otherwise carved out an hour of your day to spend with us—we raise our pirate flags to you. And to Allison Baer, TAM’s very own renaissance woman who made it all happen, you get the biggest Jolly Roger of them all. Thank you.

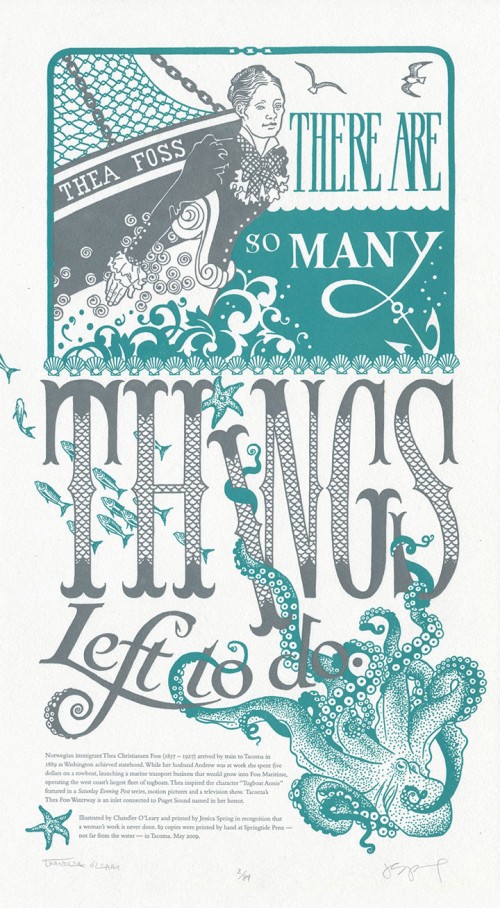

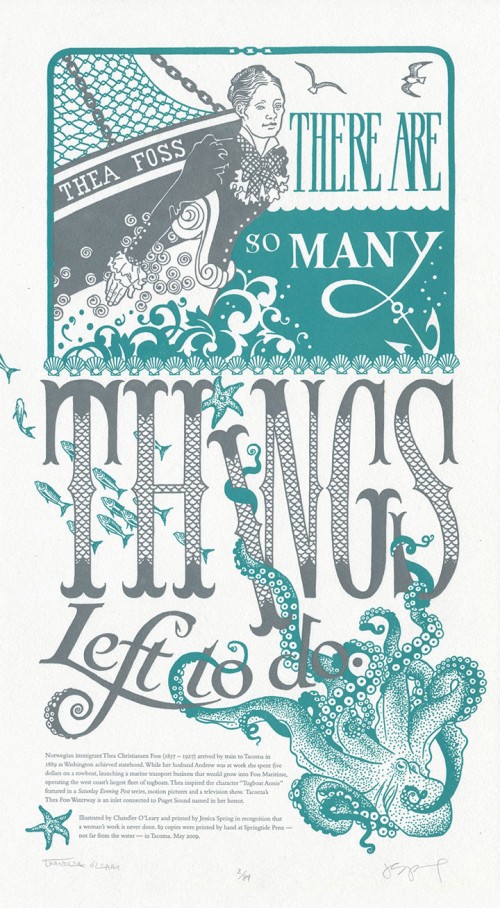

This week I’m going to post some of the things we talked about today at TAM, about the making of Tugboat Thea and our series. But for now, let’s just get down to brass tacks about the broadside. Here’s the quote that started it all:

There are so many things left to do. — Thea Foss

In honor of enterprising women everywhere, the print features business pioneer and entrepreneur Thea Foss, who founded the Foss Tugboat company in Tacoma, WA—at a time in history when it was not only courageous, but nearly unheard of for a woman to do so. Here Thea is portrayed as the figurehead of her own tugboat, surrounded by crashing waves and sea life native to her home waters of Puget Sound.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Tugboat Thea: No. 4 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 89

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Norwegian immigrant Thea Christiansen Foss (1857 – 1927) arrived by train to Tacoma in 1889 as Washington achieved statehood. While her husband Andrew was at work she spent five dollars on a rowboat, launching a marine transport business that would grow into Foss Maritime, operating the west coast’s largest fleet of tugboats. Thea inspired the character “Tugboat Annie” featured in a Saturday Evening Post series, motion pictures and a television show. Tacoma’s Thea Foss Waterway is an inlet connected to Puget Sound named in her honor.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

May 7th, 2009

Thea’s back! This is just a sneak peek of the pencil sketch for now; Jessica and I are unveiling Ms. Foss’s new look on Tuesday, so we’re saving the surprise for then. In the meantime, though, we thought we’d offer up a few snippets.

The latest broadside in our Dead Feminists series has been a little bit of a different process, at least on my end. We had the chance to create a prototype of sorts when we were asked to make steamroller prints at the Wayzgoose this year. But while several hundred people were there to witness the steamroller in action, only eight huge Tugboat Thea prints exist—not exactly ideal in the supply-and-demand sense. By redesigning the piece, we we’d no longer be limited by what we could hand-carve out of a slab of linoleum. So we let the first Thea serve as a rough draft, and took another crack at it for the official series.

This time, though, there’s a bit of a twist. That’s all I’ll say for now.

As part of the unveiling of the new Tugboat Thea, Jessica and I will be speaking at TAM on Tuesday morning. If you’re in the area, and you can fit the weird time slot into your schedule (sorry about that), here are the details:

Pressing Matters:

Contemporary Collaborations Highlighting Women in History

Tuesday, May 12, 10:30 a.m.

Tacoma Art Museum, 1701 Pacific Ave.

Tugboat Thea will be available for sale at the event, too—look for it to appear here afterward!

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)