Blog

May 30th, 2011

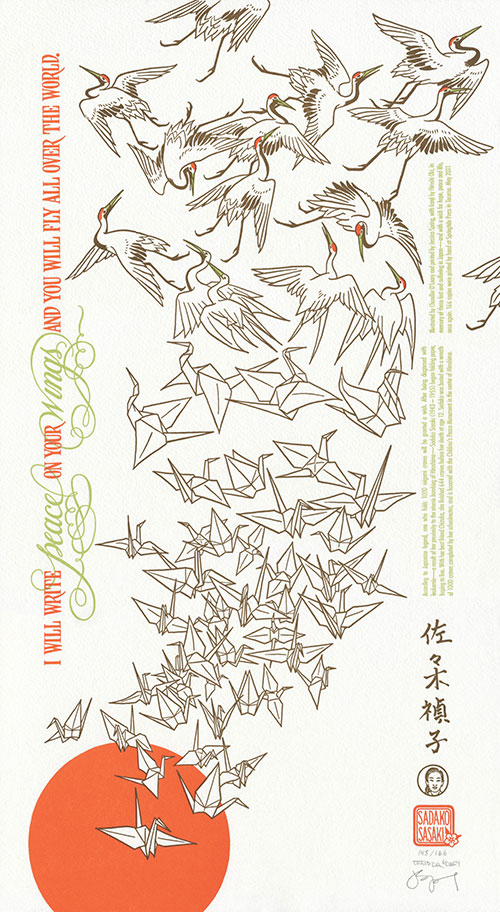

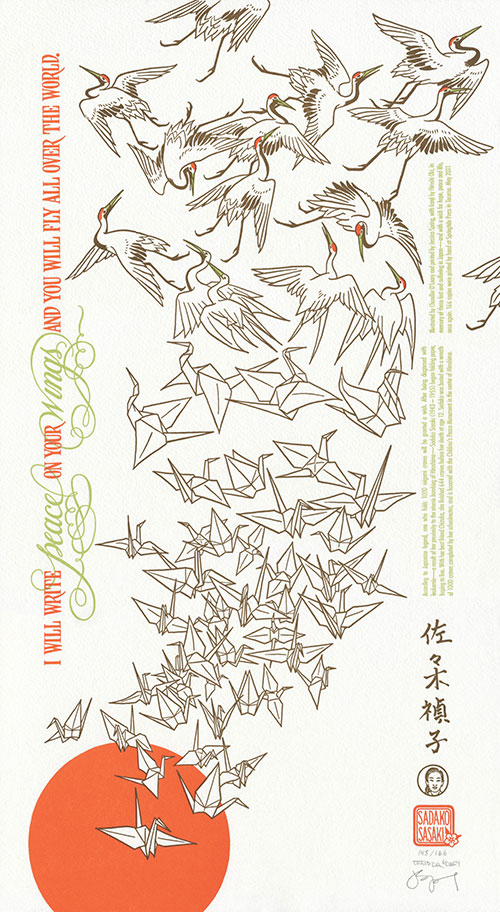

Today is Memorial Day in the United States, a holiday designated for the remembrance of those lost in time of war. But on this day, Jessica and I can’t help but extend our thoughts to others as well, in the spirit of peace. Today our eyes and hearts are trained on the far shores of the Pacific, where the people of Japan are still reeling from the March 11 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. So for our twelfth Dead Feminist broadside, we remember them by giving wings to the words of our youngest-ever feminist:

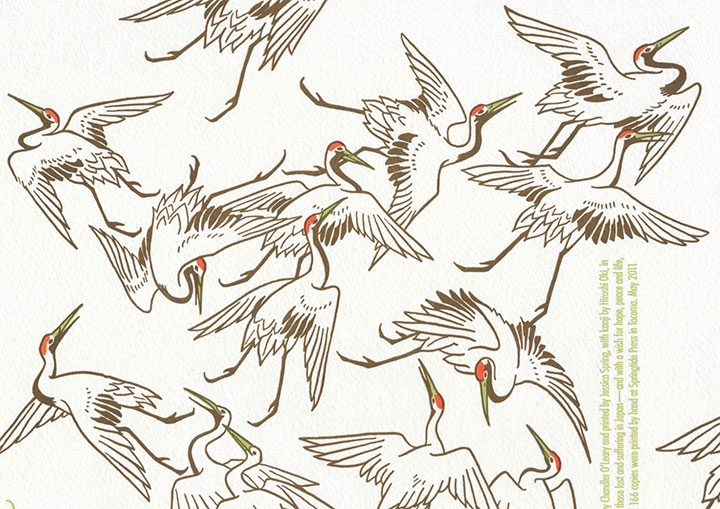

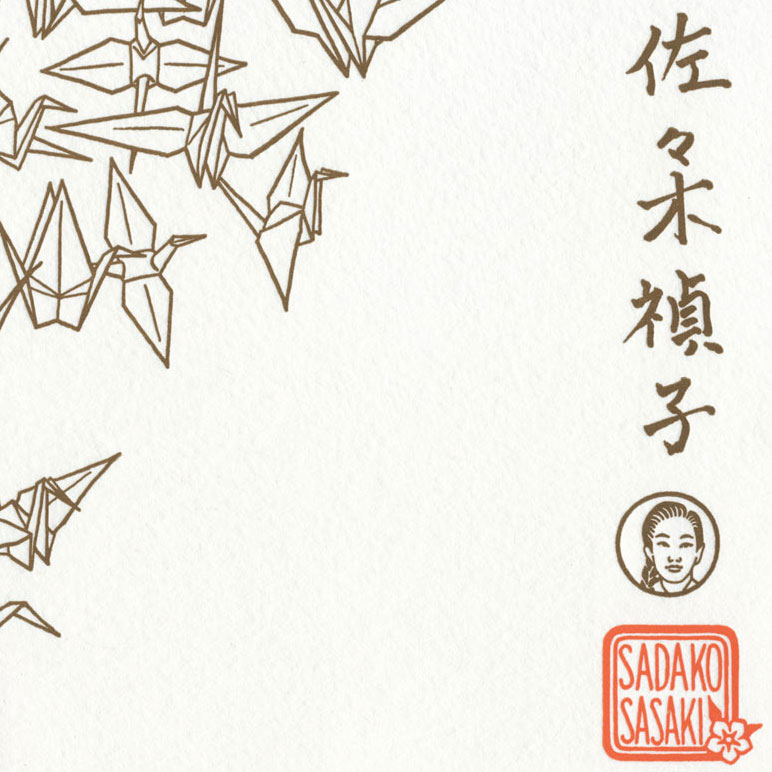

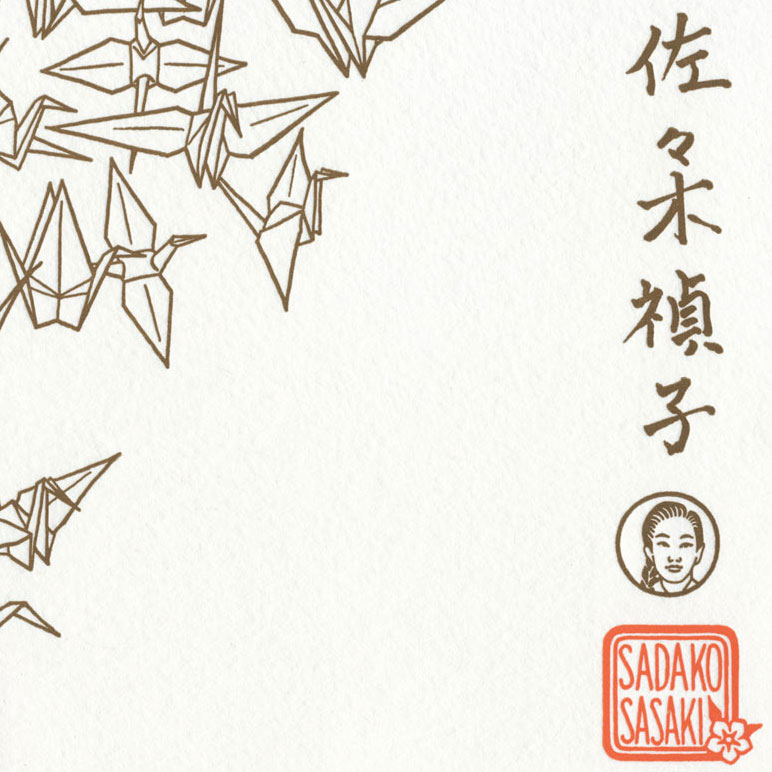

I will write peace on your wings and you will fly all over the world. — Sadako Sasaki

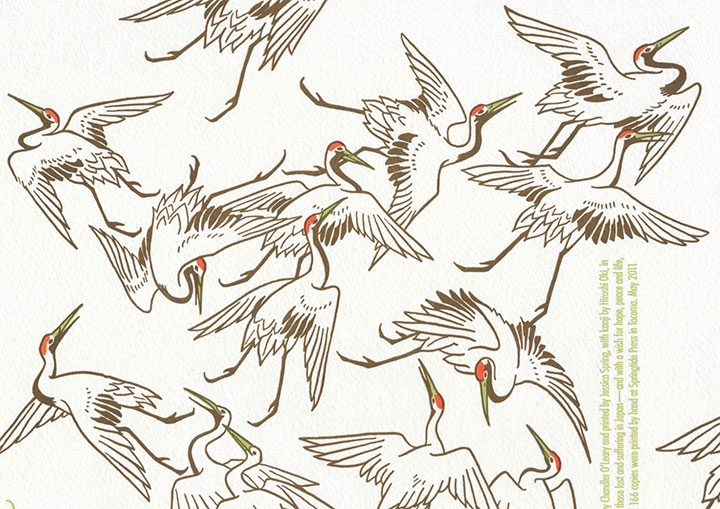

As you can probably tell, this piece is a bit of a departure from our usual way of doing things. This time it just didn’t feel right to let the typography run amok, or to fill every inch of real estate with illustrated goodies. So instead, we simply opened the door and let our imaginations take flight. The quote stands quietly apart, running parallel to a flock of origami cranes rising upward from a persimmon sun. As they follow Sadako’s words and wishes, they transform into red-crowned tancho cranes, disappearing off the page.

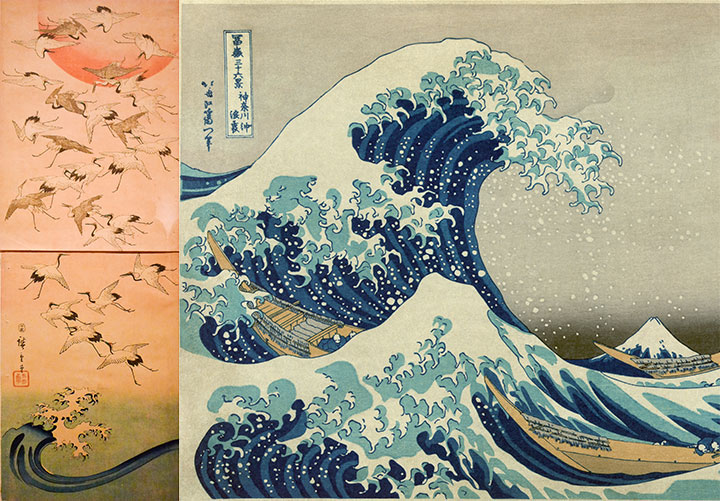

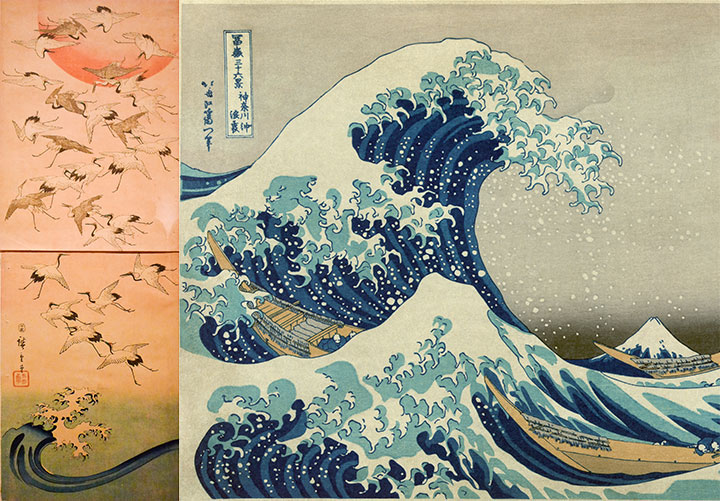

Since the traditions and history of Japanese printmaking are a veritable goldmine, the sky was literally the limit when it came to inspiration. But I had something particular in mind:

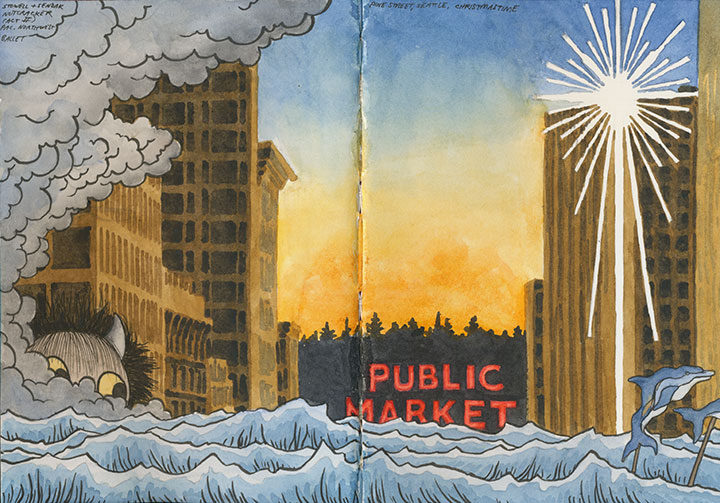

On the left is is Cranes and New Year Sun by Utagawa Hiroshige; on the right is Katsushika Hokusai’s famous Great Wave Off Kanagawa. You can see a reference to Great Wave at the bottom of Cranes—making references to both other artists and one’s own older work is a common convention in Japanese art.

I had the good fortune of seeing Cranes and New Year Sun in person earlier this year at the Tacoma Art Museum. Not only is it a beautiful image, it has an interesting quirk that sort of stuck in my craw. See that line running halfway through the composition on the left? The piece is made up of two sheets of paper; it was originally designed to function as the front and rear endsheets of a book. As far as I know, the original viewer never would have seen the image as a whole—and maybe never would have given it a second thought. But together, the two halves of the image form a stunning vertical composition that I wanted to reference for our piece.

There’s also a bit of a practical homage for us here: just as Hiroshige’s illustration is made up of two parts, each one of our Dead Feminist broadsides is also comprised of two halves. For us it’s purely a technical limitation—Jessica’s platemaker can only make plates that are about 8 x 10 inches in size. So since each of our prints is 10 x 18 inches, we have to break the illustration up and print it in two sections: one set of plates for the top, and another for the bottom. So that means that somewhere in every one of our broadsides, there’s a little break running horizontally through the composition. We usually try to hide it as cleverly as possible, or at least blend it in with the overall design, but it’s always there. Take a look at some of our previous prints and see if you can find it. (Mind the gap!)

Anyway, Hiroshige is not the only person we have to thank for all of this. I’d also like to send out a special, winged bit of gratitude to Hiroshi Oki for providing us with his exquisite kanji (Japanese calligraphy) rendition of Sadako’s name—and to his daughter Shiori for introducing us.

The thing that has just enchanted us both about this project is the very idea of imbuing paper with a wish—of creating something so labor-intensive and time consuming, and then sending it out into the world for a greater purpose. Sadako wasn’t the only person to fold cranes for a wish, but she might be the most well-known. Every year, on the anniversary of the atomic bombing, Sadako’s monument in Hiroshima is festooned with thousands upon thousands of cranes—so many that permanent shelters have been erected there to house and protect them. And even in Western countries, it’s become somewhat of a tradition to give senbazuru (a set of 1000 paper cranes) as a gift to cancer patients. Talk about a ripple becoming a tidal wave.

In that spirit, we’ll be donating a portion of our proceeds to Peace Winds America, a non-profit organization based in Seattle and dedicated to disaster response worldwide. The donation will be directed to the Japan Relief & Recovery Fund, used to rebuild local infrastructure and restore the livelihoods and communities of those affected by the earthquake and tsunami. We’d like to think of this as a little senbazuru of our own.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Peace Unfolds: No. 12 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 166

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

According to Japanese legend, one who folds 1000 origami cranes will be granted a wish. After being diagnosed with leukemia—a result of her proximity to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—Sadako Sasaki (1943 – 1955) began folding paper, hoping to live. With her best friend Chizuko, she finished 644 cranes before her death at age 12. Sadako was buried with a wreath of 1000 cranes completed by her schoolmates, and is honored with the Children’s Peace Monument in the center of Hiroshima.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, with kanji by Hiroshi Oki, in memory of those lost and suffering in Japan—and with a wish for hope, peace and life, once again.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

April 19th, 2011

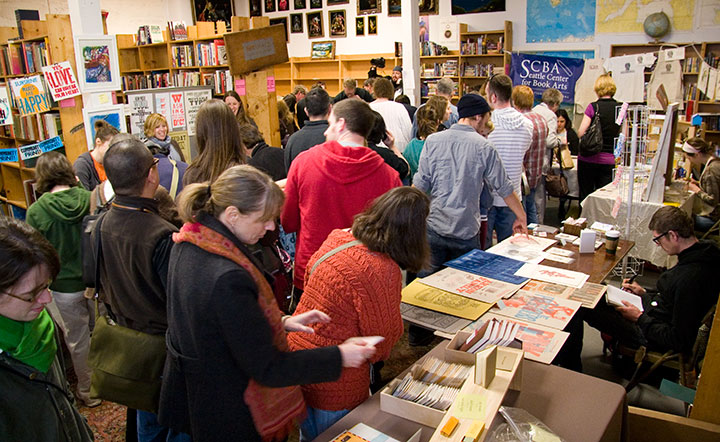

Holy flying gaggles, but we upped the ante this year!

I don’t know if it was the gorgeous sunshine that graced us after literally months of dreary rain—

—or Sweet Pea’s extra-awesome 2011 poncho—

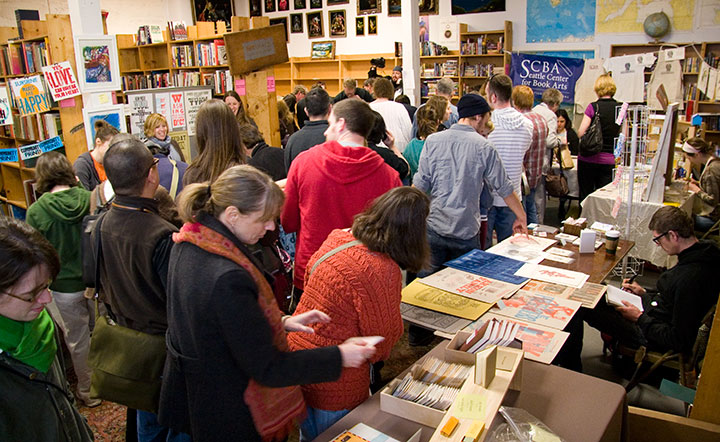

but this year’s Wayzgoose was larger than life.

(In case you’re curious, that little Sigwalt press is inked up to print “I got goosed in Tacoma!” in an eye-frying safety orange that would make any Ducks Geese Unlimited hunter proud. I mean, come on—we have standards. This is some high-brow entertainment here.)

Anyway, speaking of geese…

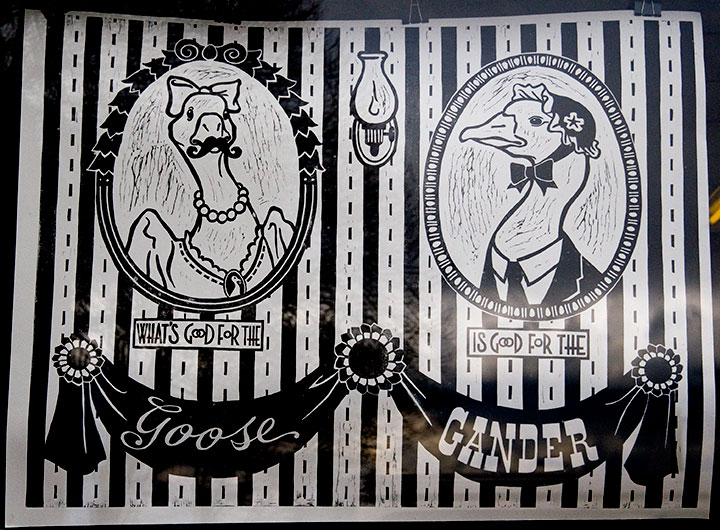

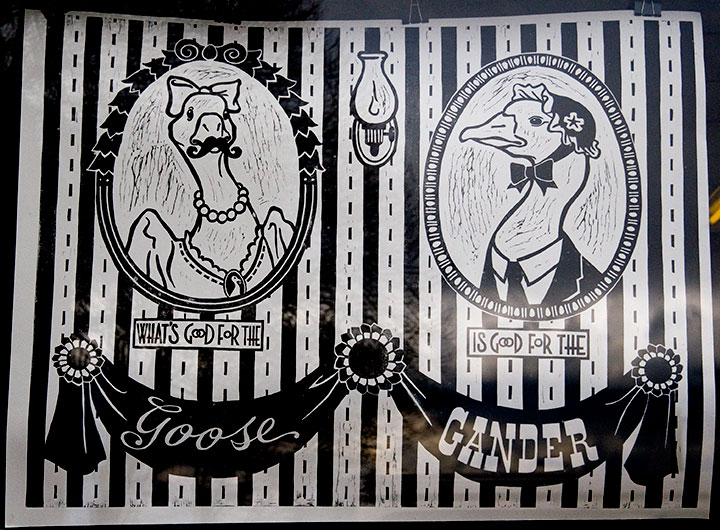

Ta-daaaa!

As you can see, we took our little Dead Feminists theme somewhat loosely this time. And in fact, we’ve dubbed our print Lucy Goosey, so there! There is a bit of a story behind this one, though. We’ve been equal parts amused and annoyed by the recent crafty and pop-cultural trends involving moustaches and putting birds on things—and for months I’ve been threatening to put a moustache on a bird on something, just to prove a point. I don’t know what that point is, exactly, but I figured it was time to put my moustache where my mouth is.

Which reminds me:

we weren’t kidding about the ‘stache wax. Hey, if you’re going to go, go all out.

Jessica seemed perfectly at home while operating heavy machinery and sporting a full-on Wilford Brimley look—

I mostly just looked like Ned Flanders. Good God, but that mustache looks real on me. Sheesh!

That’s okay, though—synchronized inking is serious business, and we don’t mess around.

Many, many thanks to all the supporters, enthusiasts and volunteers who turned out in droves;

to Katy Meegan and Mary Holste for snapping ‘stache shots for us;

to King’s for being the host with the most;

and to the Tacoma Arts Commission for sponsoring our steamroller shenanigans.

So … tell me.

Is it too soon to start cookin’ up next year’s ‘goose?

February 18th, 2011

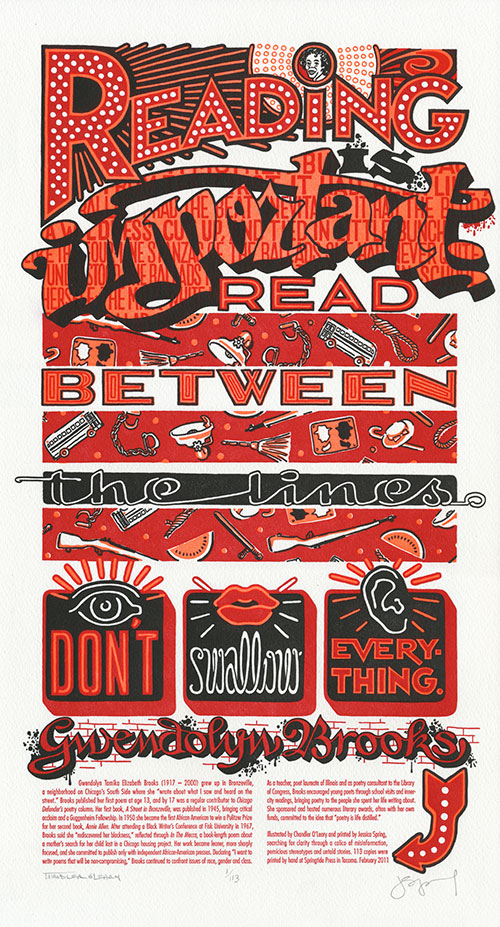

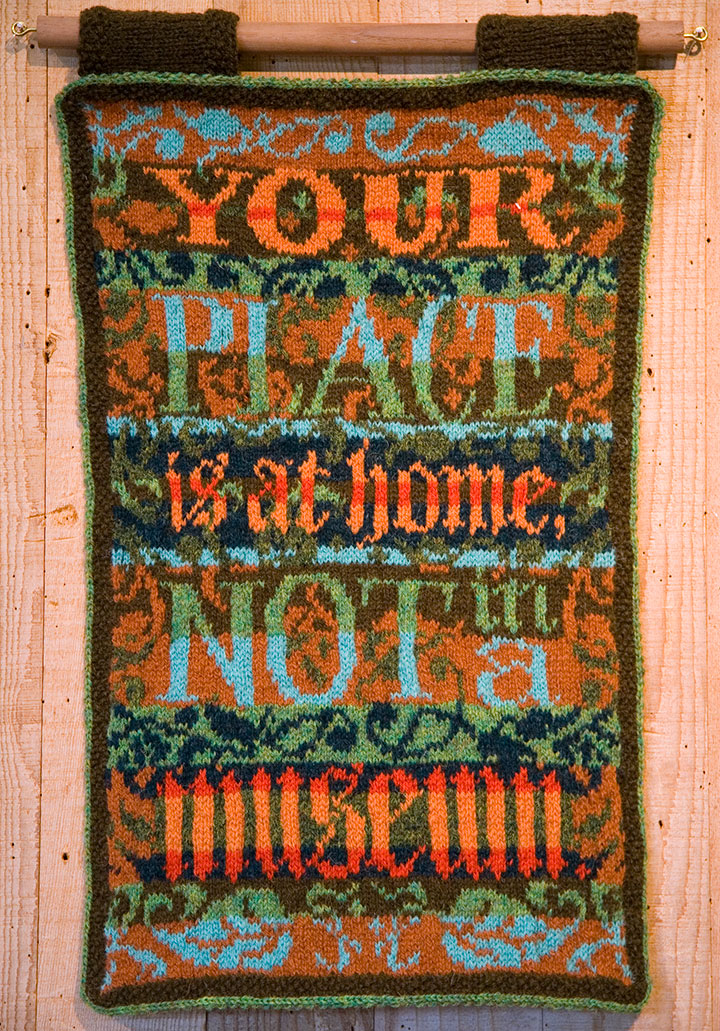

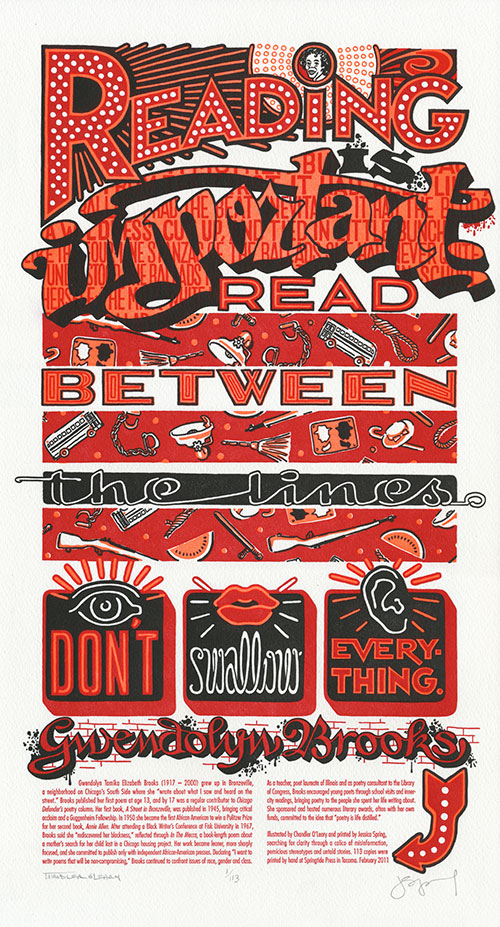

In honor of Black History Month, and of the might of the written word, our newest Dead Feminist is powerhouse poet Gwendolyn Brooks. Without further ado, I’ll hand over my pen to her:

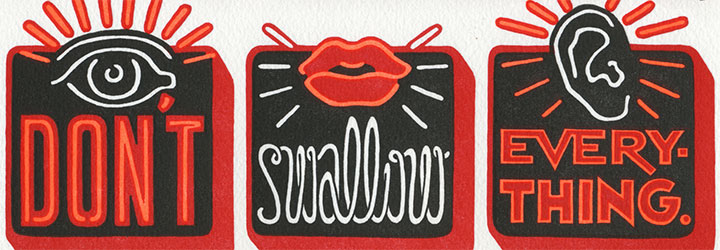

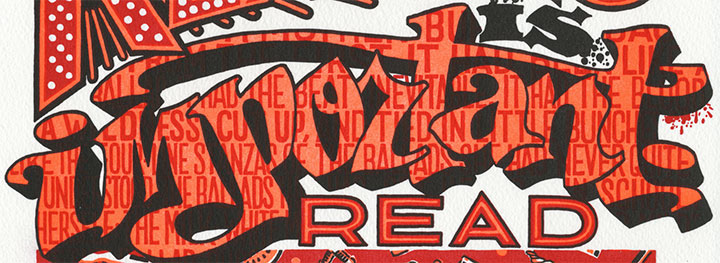

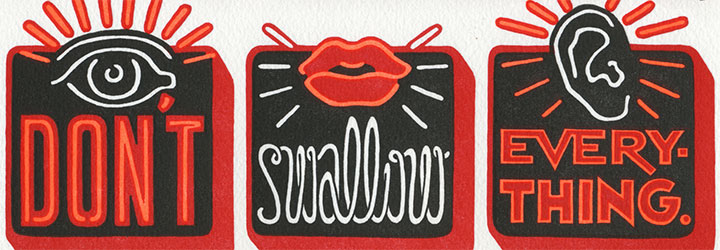

Reading is important. Read between the lines. Don’t swallow everything.

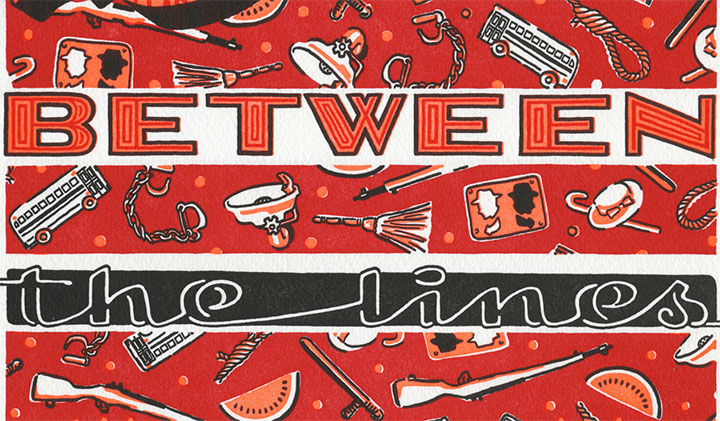

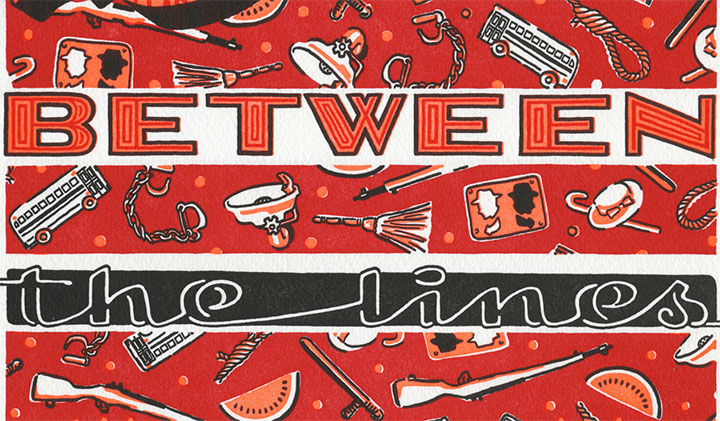

I guess we’re done with the knitting needles and home canning for now; time to don the boxing gloves. This was a tough one, and we almost didn’t have the gall to go through with it. But Gwendolyn Brooks was never one to pull a punch; she faced and shed light on the most uncomfortable truths with bravery and eloquence. And there seem to be an awful lot of uncomfortable truths floating around lately; like a certain congressperson’s assertion that our nation’s founding fathers ended slavery, or the fact that no matter how many African American Presidents we elect, racism isn’t dead. (Don’t believe me? Even my most cursory historical research brought up all sorts of fresh, modern hatred. Try it for yourself and do an online image search for “watermelon stereotype”—if you can stomach it. Just keep an airsick bag handy, because it ain’t pretty.)

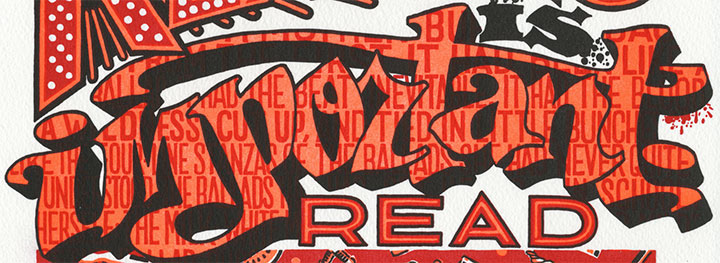

So in tribute to Brooks’s courage, Warning Signs is a riot of color and fluorescent ink, glowing like an urban beacon. Flashing neon and spattered graffiti confront us, sounding the alarm with every word. Beneath the fluorescent current runs a blood-red repeating calico pattern of violence and cruelty—a tapestry that forms the unfortunate warp to the weft of our past and present.

And as an undercurrent to the undercurrent, behind the graffiti reads the first stanza of Brooks’s poem, “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon.” The poem grapples with the brutal 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till, and weaves a tale of remorse and confusion from the perspective of Carolyn Bryant, the white woman whose accusations that Till flirted with her provoked her husband to abduct and kill the boy. But we didn’t choose the poem for its subject matter, per se—we chose it for the articulate beauty with which Brooks tells the story. It’s still a punch to the gut, but when she knocks you flat you see some awfully pretty stars.

A portion of the proceeds from Warning Signs will be donated to 826CHI, a non-profit Chicago writing and tutoring center. 826CHI is dedicated to supporting the writing skills of students ages 6 to 18, and to helping teachers inspire their students to write—their mission is to “strengthen each student’s power to express ideas effectively, creatively, confidently, and in his or her individual voice.” We think Ms. Brooks would approve.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Warning Signs: No. 11 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 113

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Gwendolyn Tamika Elizabeth Brooks (1917 – 2000) grew up in Bronzeville, a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side where she “wrote about what I saw and heard on the street.” Brooks published her first poem at age 13, and by 17 was a regular contributor to Chicago Defender’s poetry column. Her first book, A Street in Bronzeville, was published in 1945, bringing critical acclaim and a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1950 she became the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for her second book, Annie Allen. After attending a Black Writer’s Conference at Fisk University in 1967, Brooks said she “rediscovered her blackness,” reflected through In The Mecca, a book-length poem about a mother’s search for her child lost in a Chicago housing project. Her work became leaner, more sharply focused, and she committed to publish only with independent African-American presses. Declaring “I want to write poems that will be non-compromising,” Brooks continued to confront issues of race, gender and class.

As a teacher, poet laureate of Illinois and as poetry consultant to the Library of Congress, Brooks encouraged young poets through school visits and inner-city readings, bringing poetry to the people she spent her life writing about. She sponsored and hosted numerous literary awards, often with her own funds, committed to the idea that “poetry is life distilled.”

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

February 2nd, 2011

I’m giggling like a schoolgirl, now that my new Naughty Undies valentine is here! This is my latest pop-up card collaboration with Igloo Letterpress—Allison came up with with the mischievous rhyme and die-cut structure, and I did an entirely typographic illustration of a pair of pink unmentionables. Want to make your Valentine’s eyes pop a little? You can pick up your card in the shop!

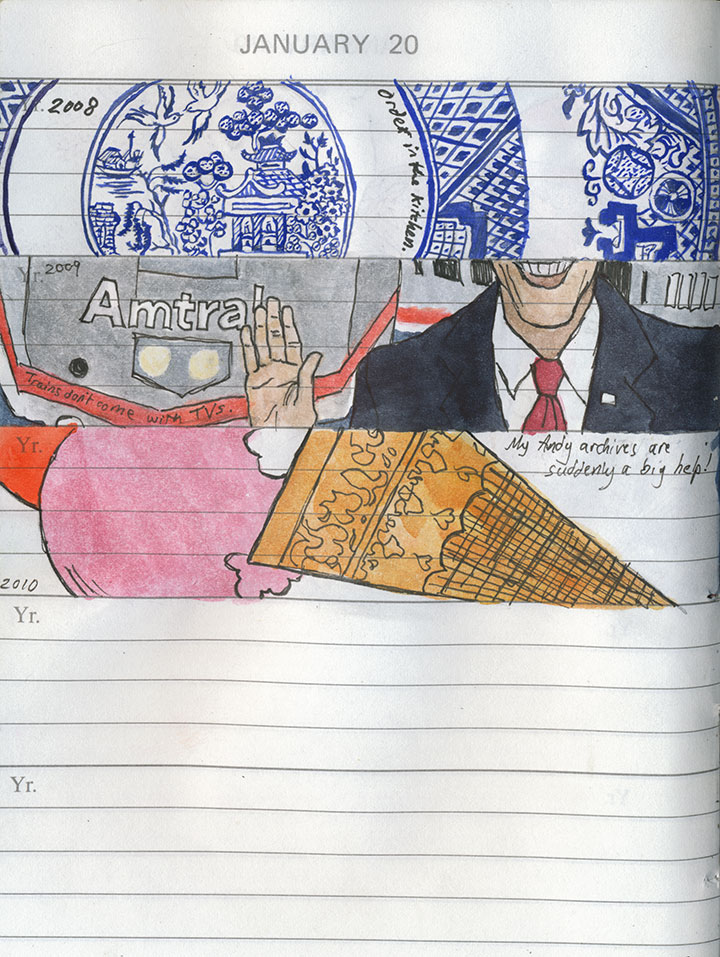

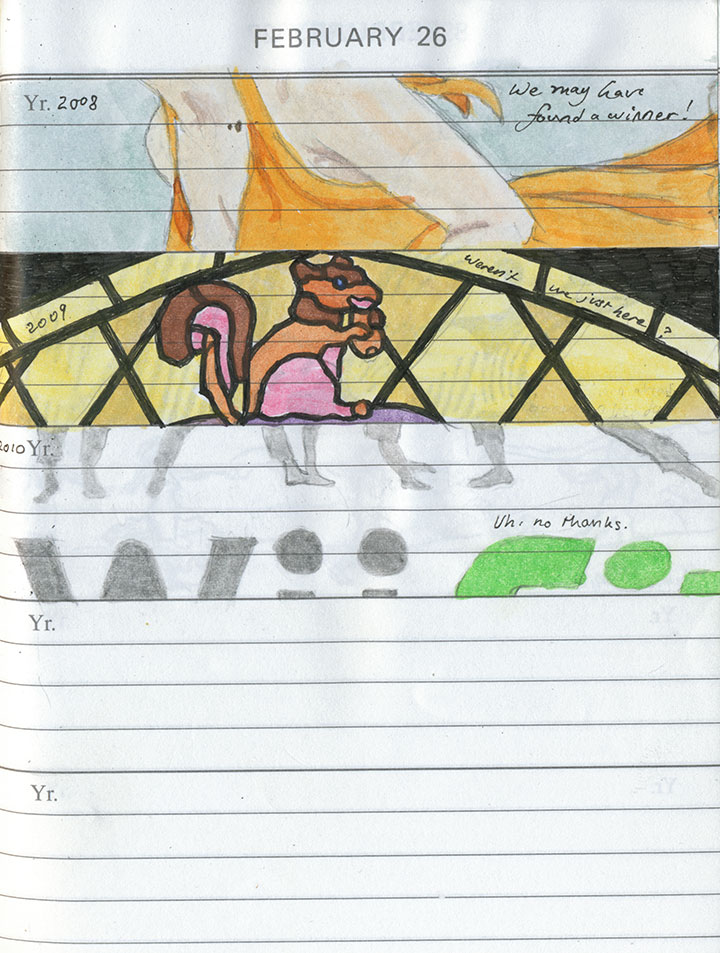

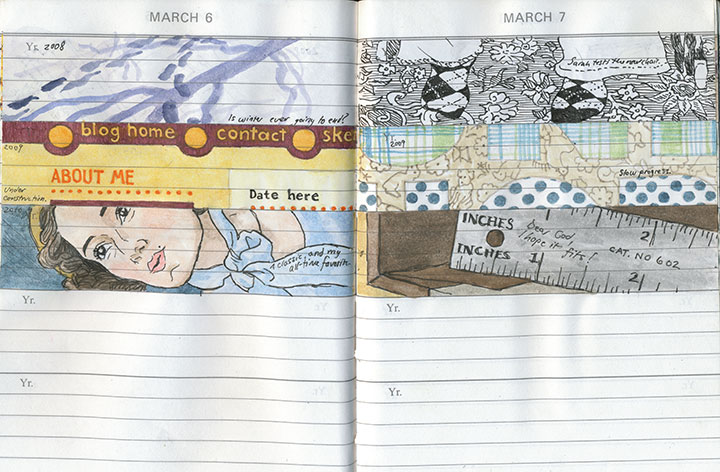

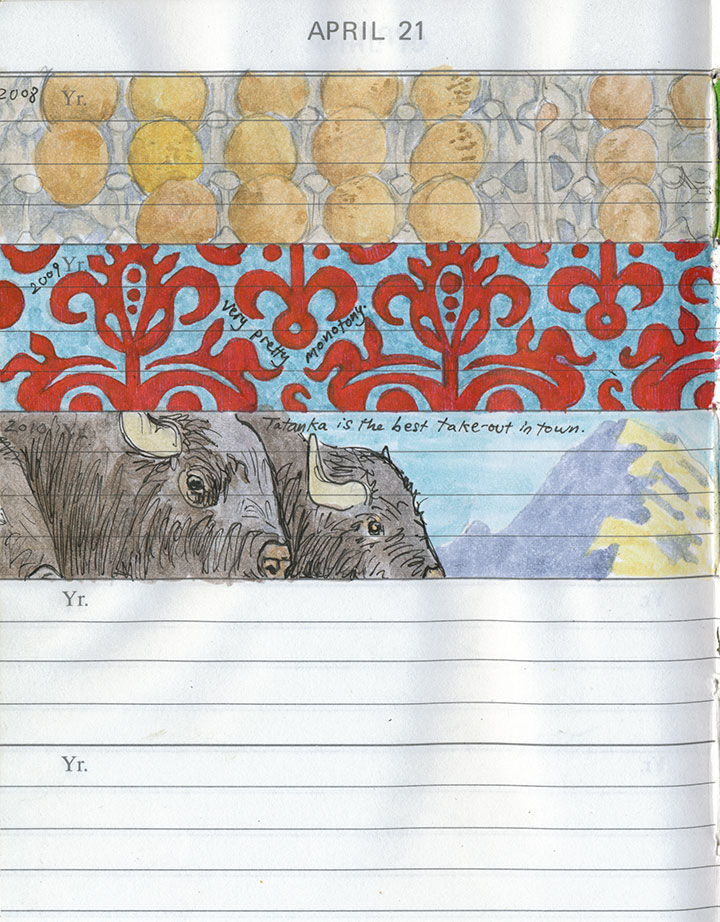

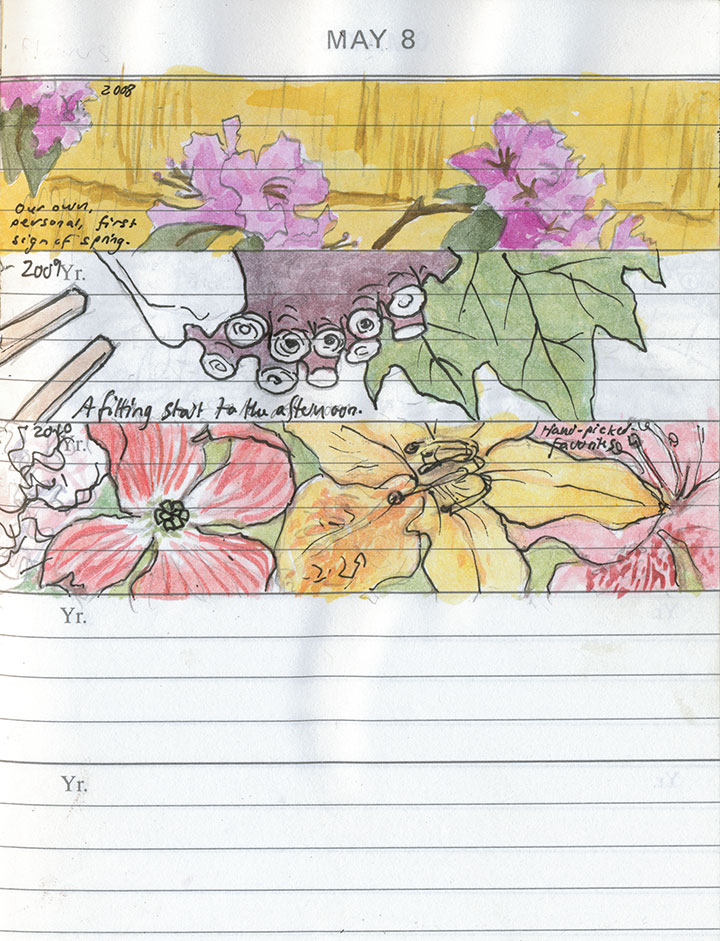

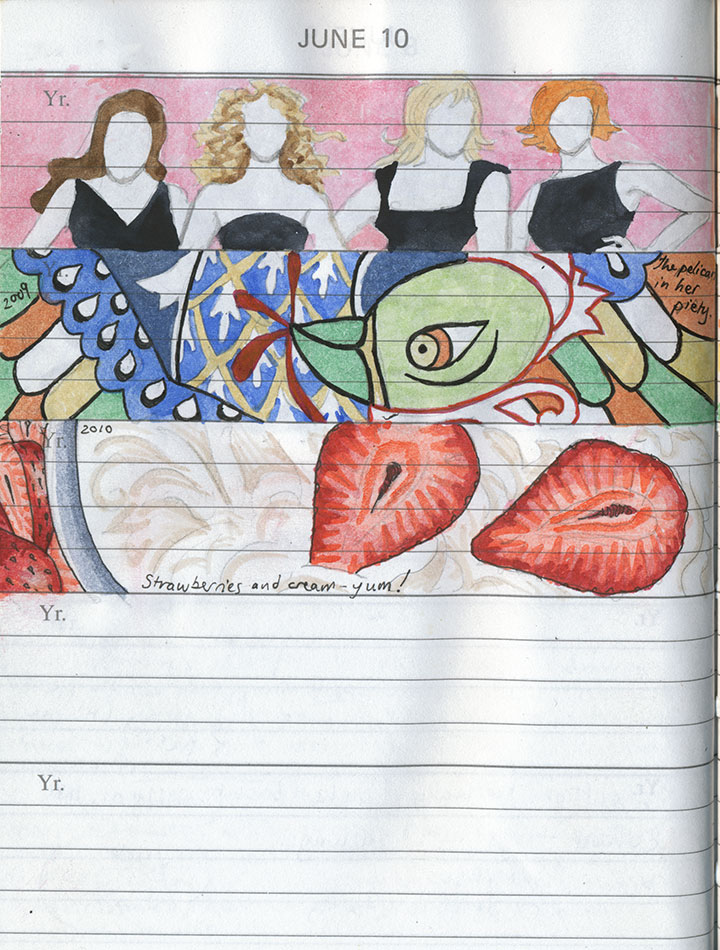

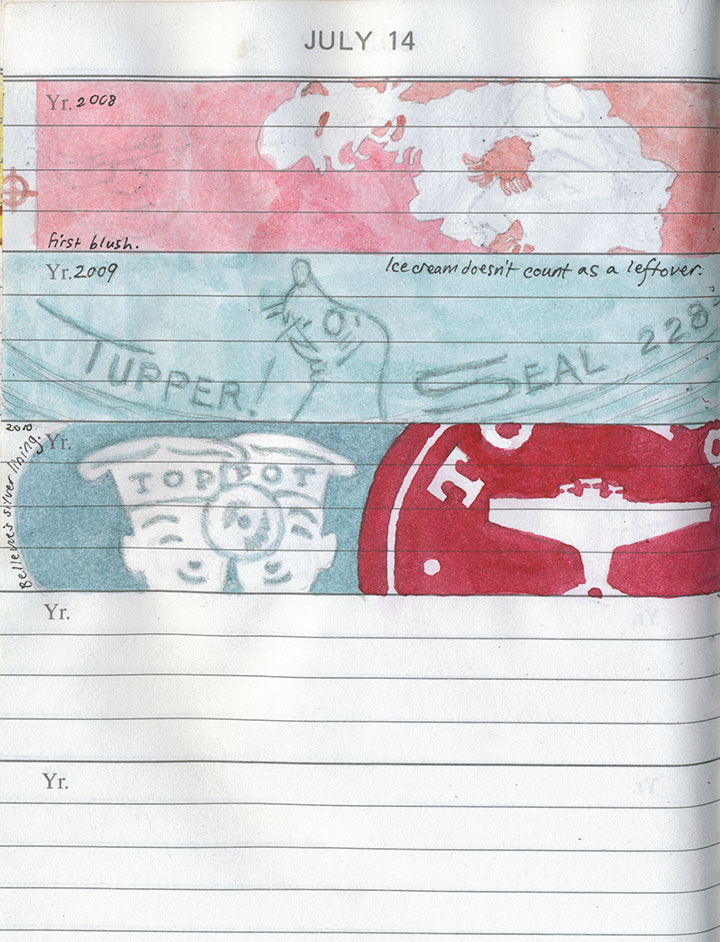

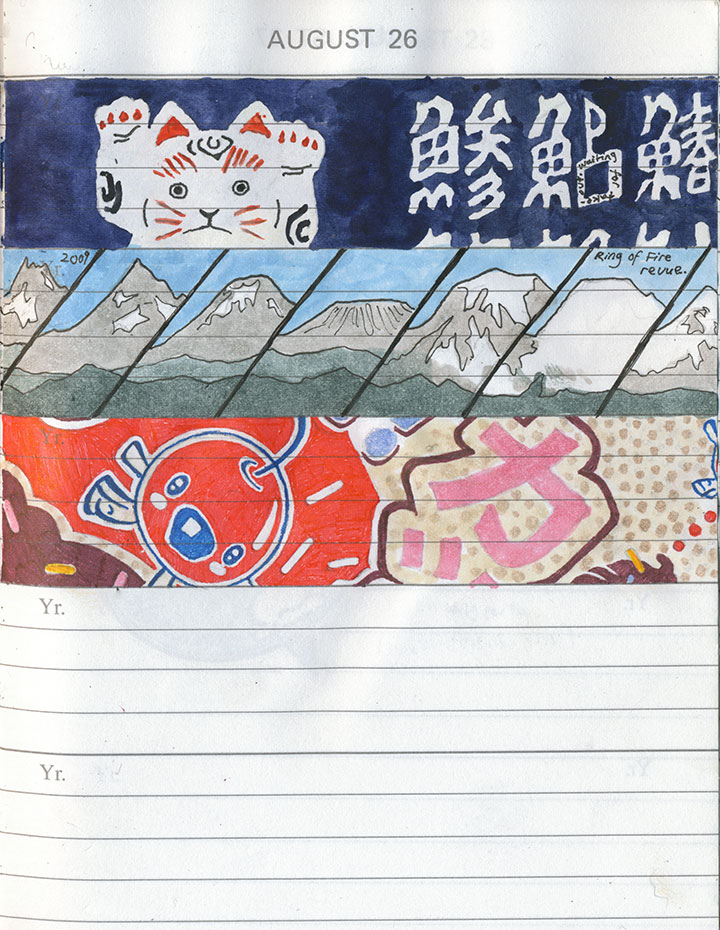

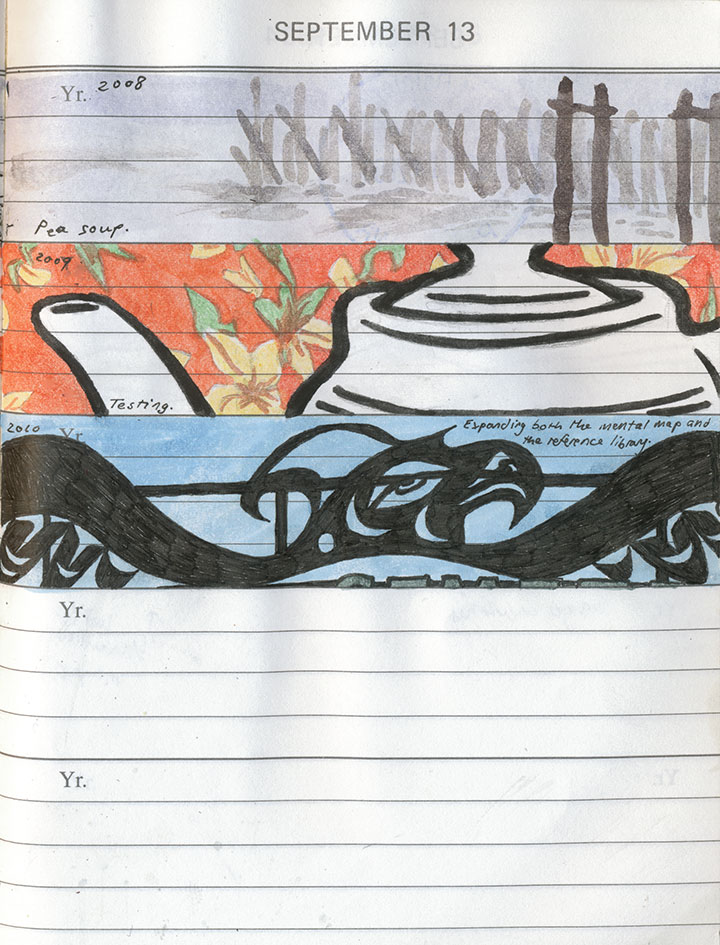

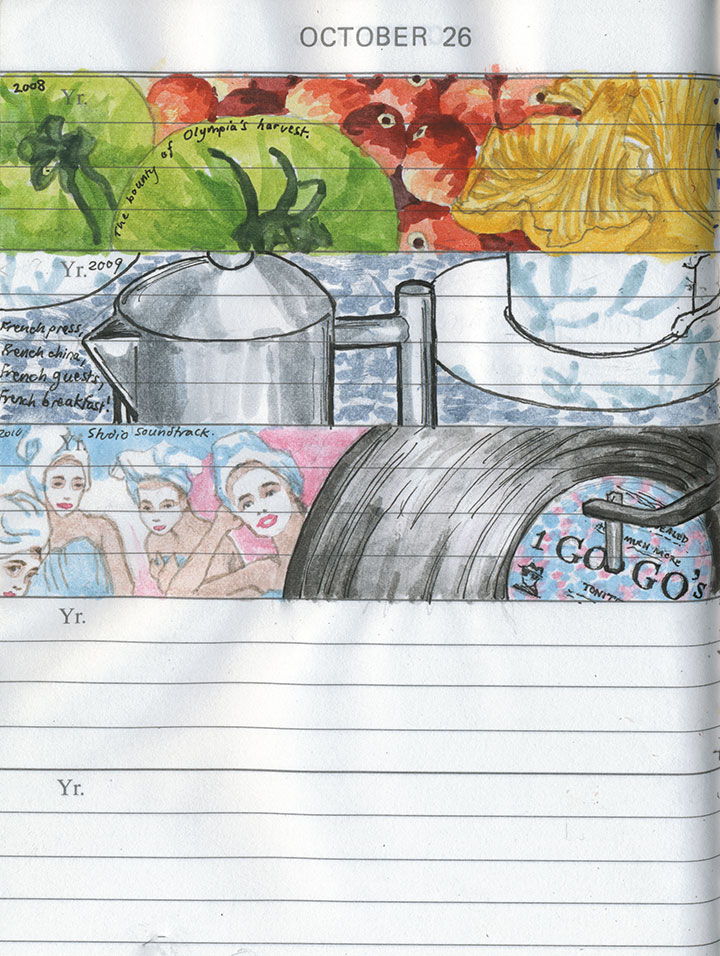

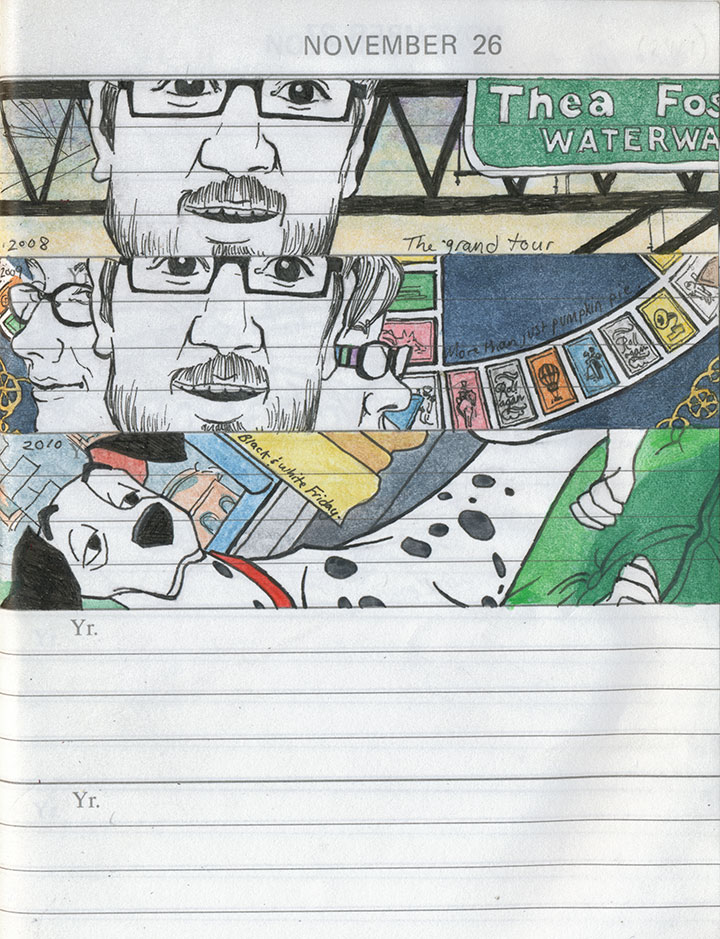

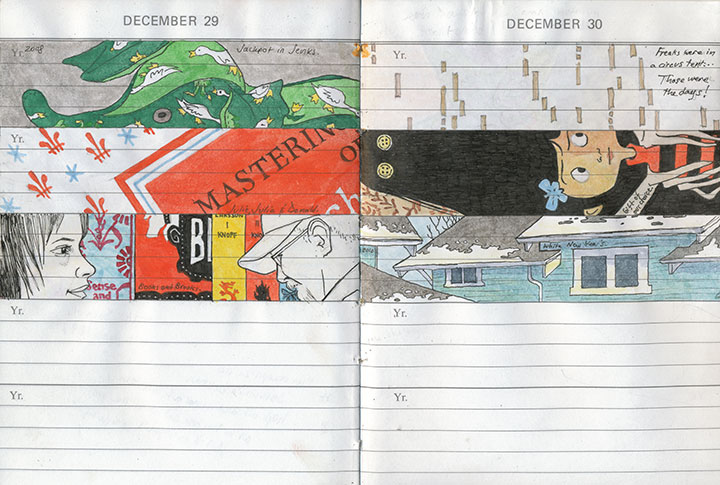

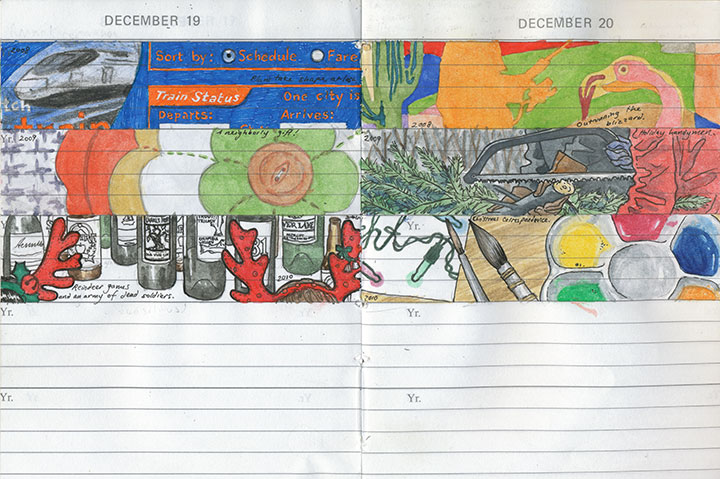

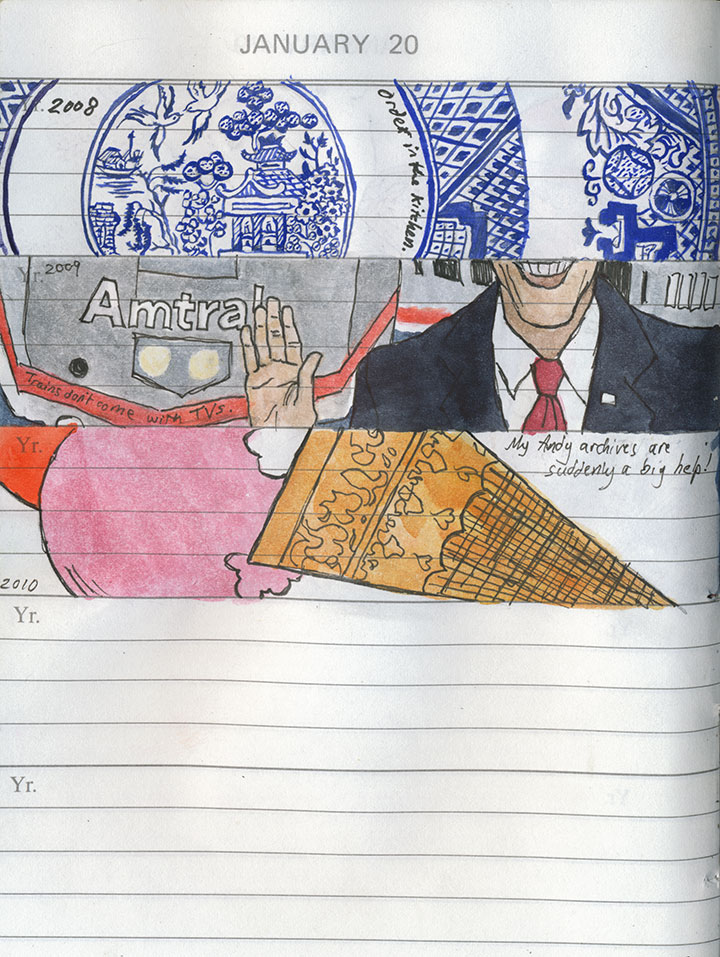

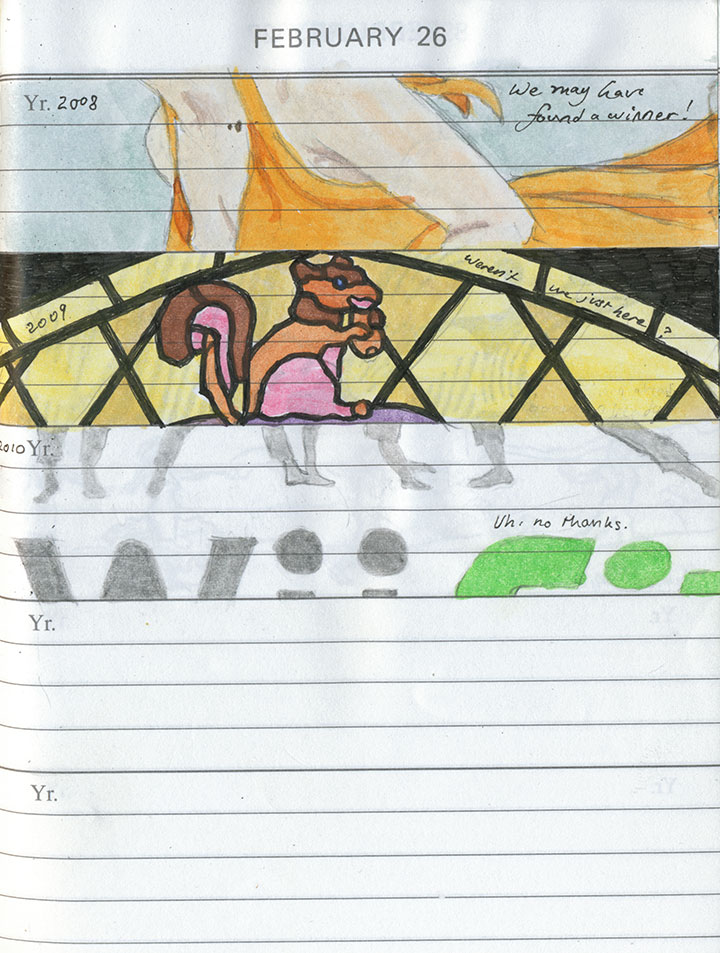

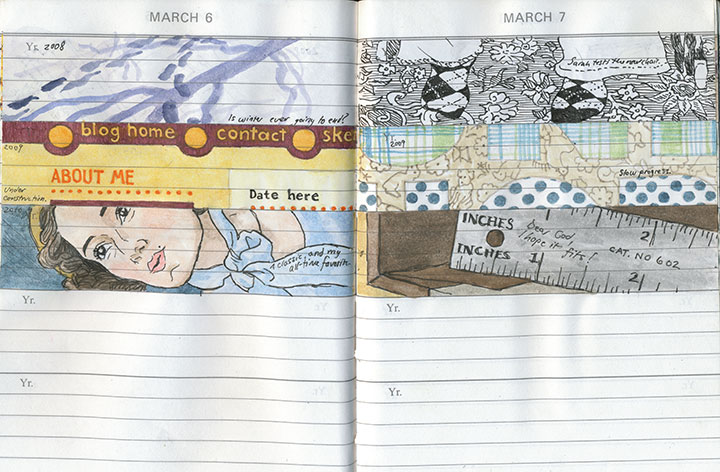

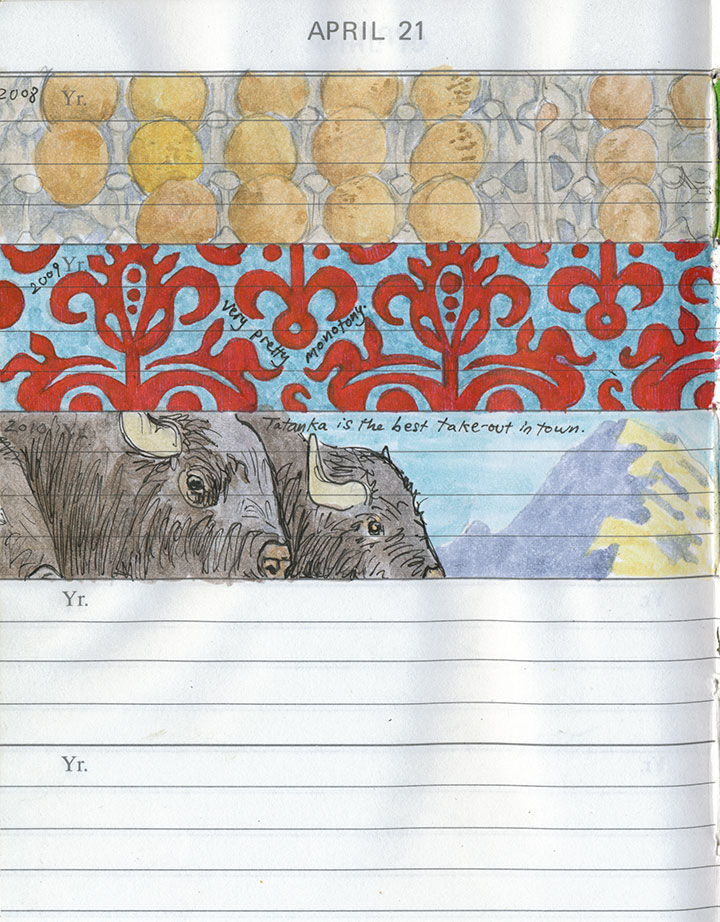

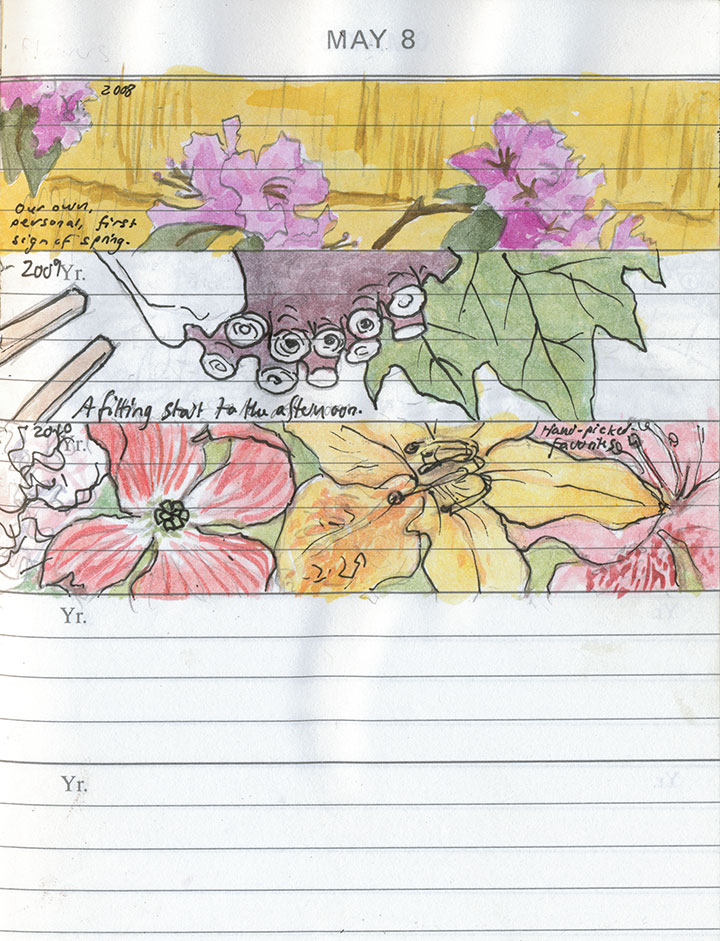

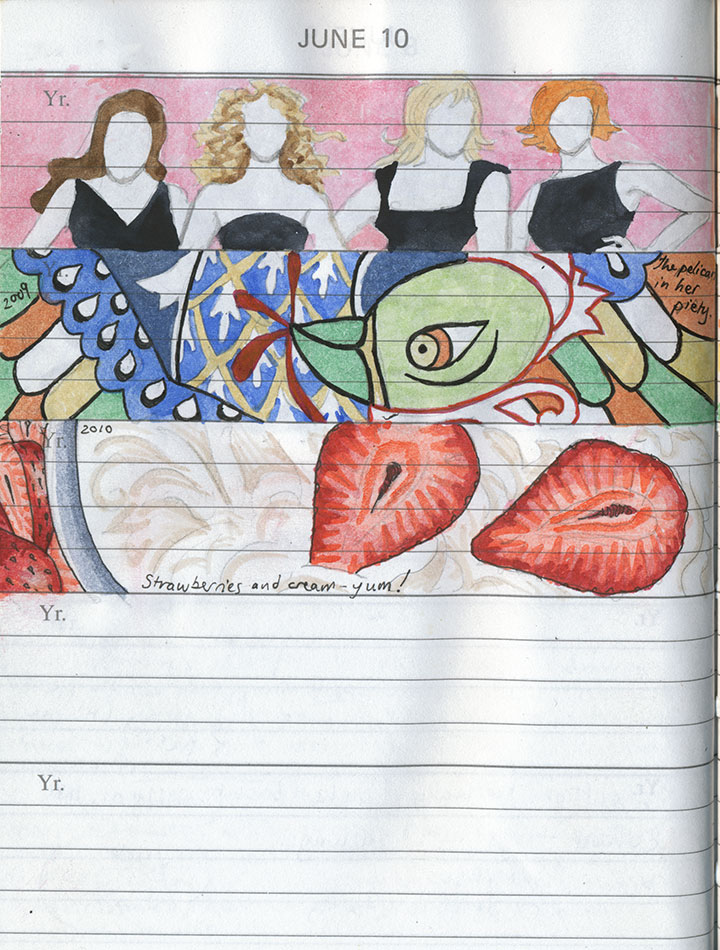

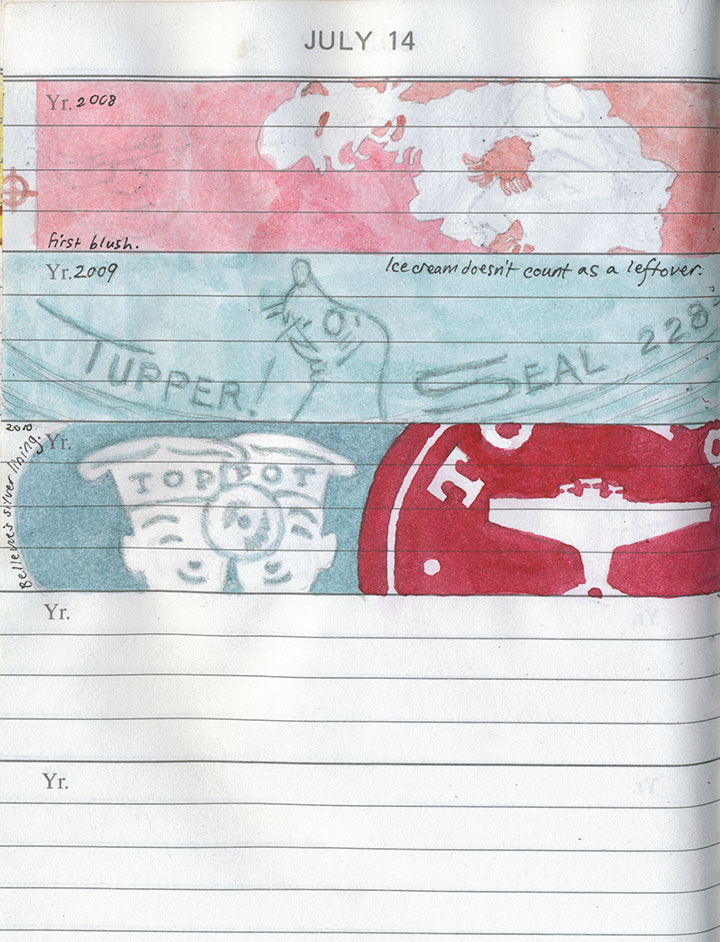

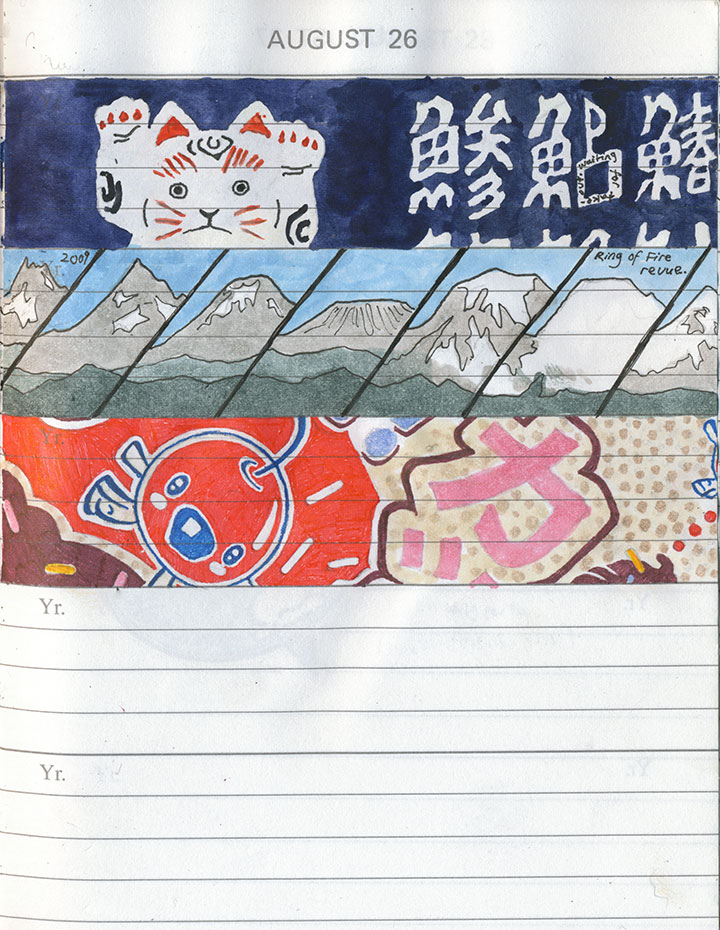

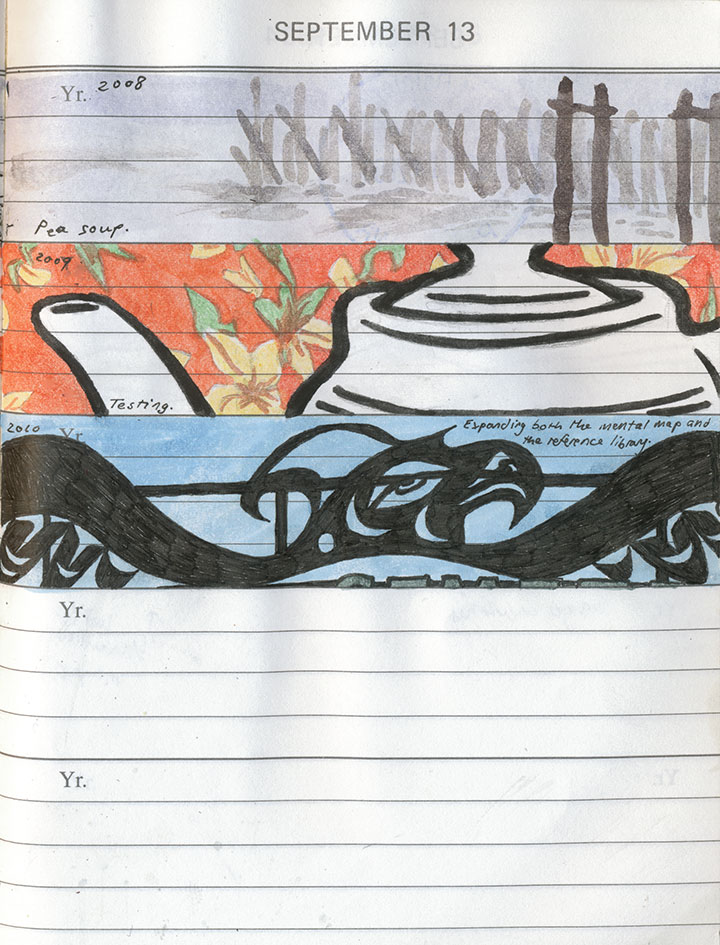

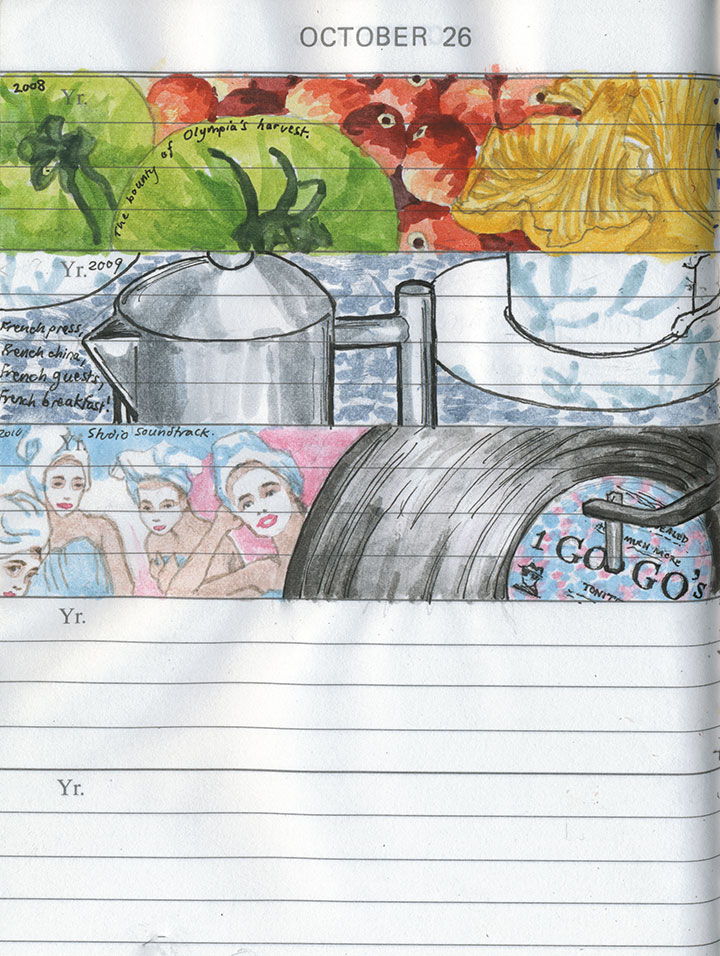

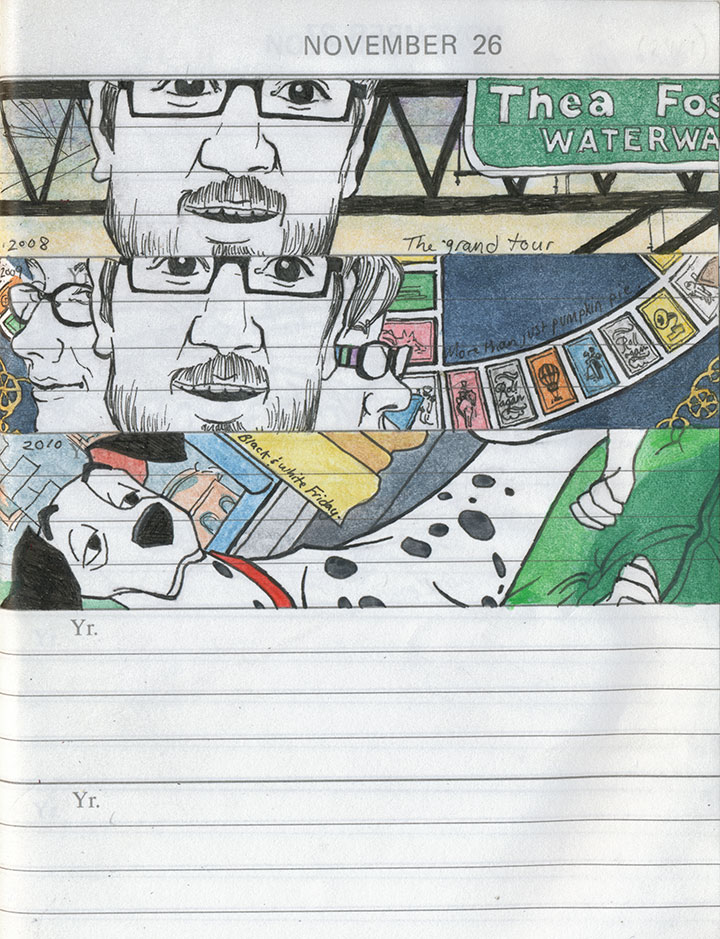

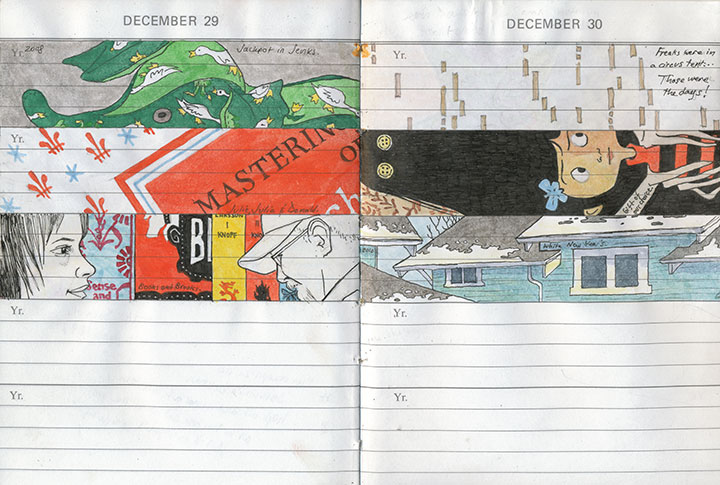

January 1st, 2011

This might seem a little strange, coming from me, but the New Year’s resolution at the top of my “art” category is to draw more.

I mean that I’d like to spend more time with my sketchbooks—with everything else that happened last year, there just didn’t seem to be a spare second for observing the moment and jotting it down.

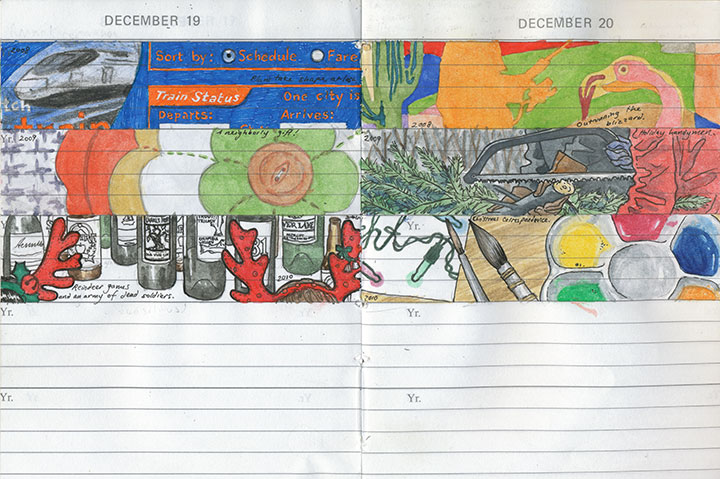

The daily book was about the only thing that received any attention, and even it spent the entire year on the back-back-back burner.

I still have quite a bit of catching up to do there, though—

so that’s where I’m going to start.

It’s a daunting prospect; even just filling in half-finished sketches (maybe I should have shown you those instead!) amounts to a huge time investment, and a mountain of work.

But I’ll get there. And besides, it’s those last two blank slots on every page that interest me the most.

They stand for the future that’s unwritten, and I find I can’t imagine what could possibly complete the picture—nor could I ever have predicted what has ended up here thus far.

When I first started this project, it seemed like a painfully slow undertaking.

But now I’m surprised at how quickly the book is filling up,

and I’m anxious to find out what will fill out this page—and the next, and the next.

Well, today I flip the book back to the beginning, pencil in hand—and so I’ll find out soon enough.

Happy New Year!

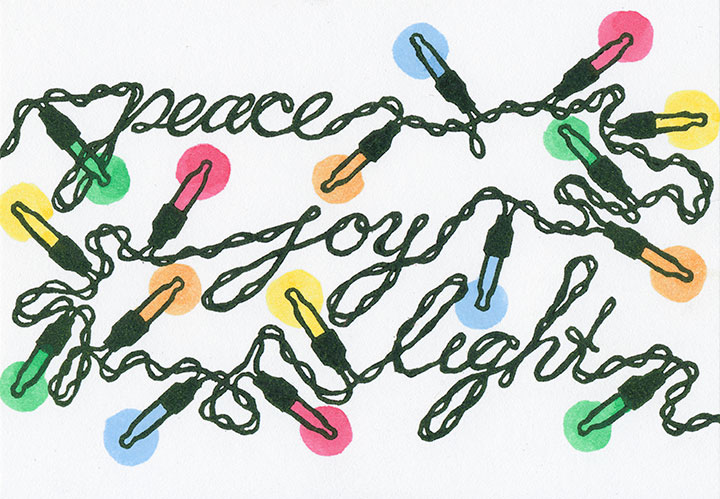

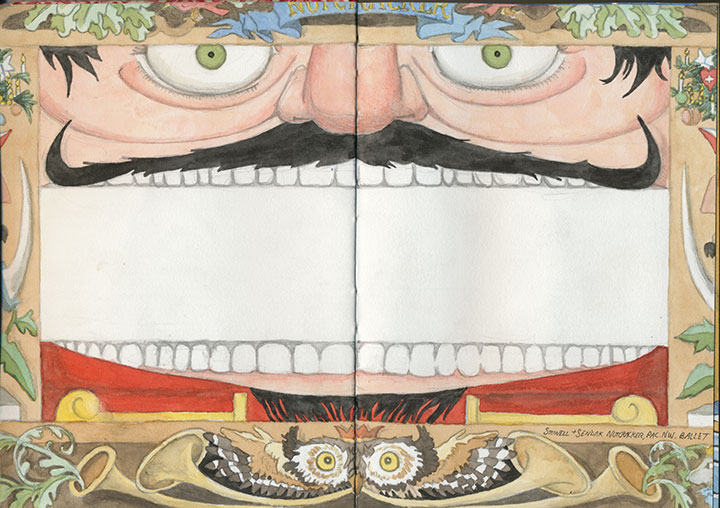

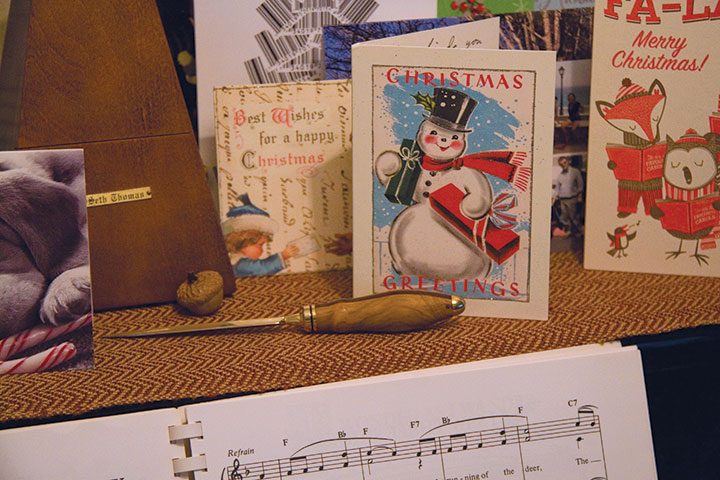

December 25th, 2010

I was afraid I wasn’t going to have any holiday photos to show you—when I was in Portland the other week, my camera took a nosedive after being bumped off my shoulder in a crowded room.

Snippets from my daily journal

So I shipped the lens off to the good folks at Canon for repair, and switched to paper for awhile.

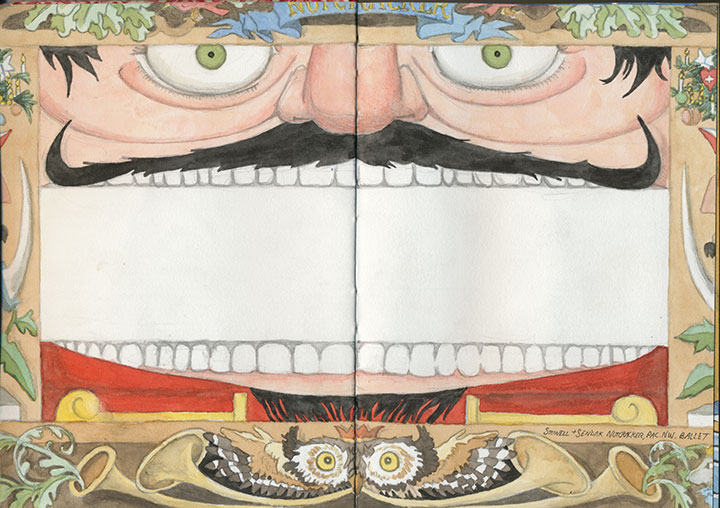

One of Maurice Sendak’s eye-candy stage sets for the Pacific NW Ballet’s Nutcracker

My favorite thing about sketchbooks is that I can take them anywhere—including places where cameras, functioning or not, are strictly verboten.

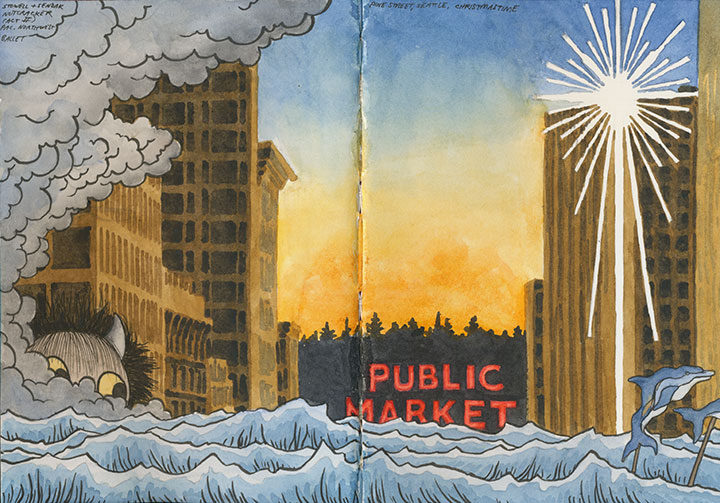

More Nutcracker scenery, plus Christmas on Pine Street in Seattle

The downside, though, is that it takes me a lot longer to draw a picture than to shoot one—so my output is always smaller than I’d like.

But then the Fedex guy showed up with my lens, good as new and just in time for Christmas.

I managed to refrain from hugging him, and then hopped around the house in manic glee, documenting the holiday the Tailor and I have spent all week creating.

(We finally broke down and bought twinkle lights for the tree; which provided the perfect inspiration for this year’s card!)

Wherever today finds you, have a warm, cozy, abundant, and very merry Christmas.

November 25th, 2010

We’re just about to set the table and raise our glasses. Wherever today finds you, and whatever is on your plate, have a warm and happy Thanksgiving!

November 10th, 2010

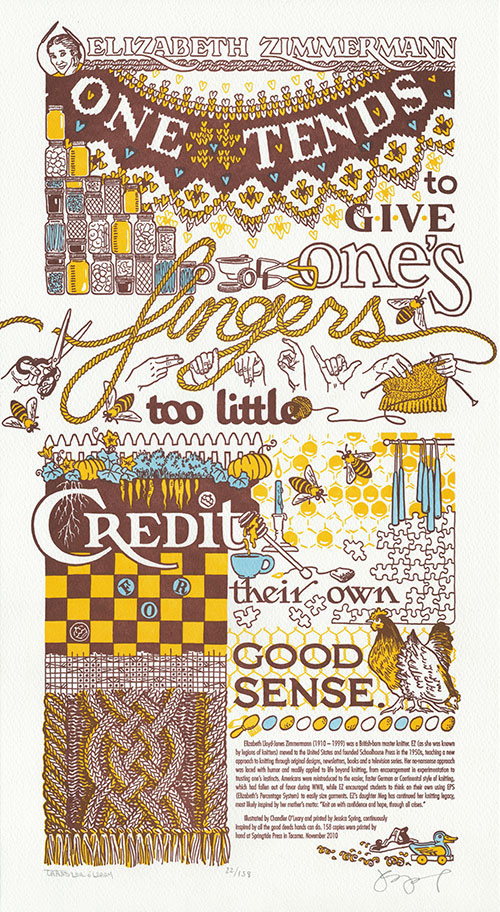

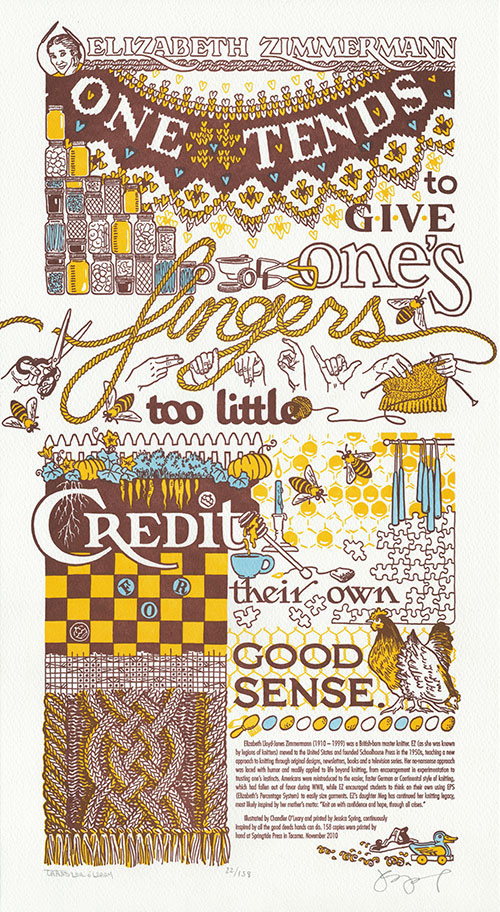

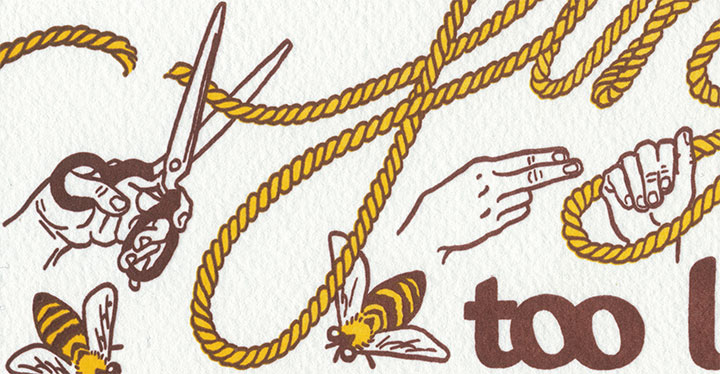

Maybe it’s the changing seasons. Or the fact that the farmers market runneth over with delicious autumn goodies. Or maybe we just wanted to talk about something that made us smile, for a change—because this time, for our tenth Dead Feminist broadside, Jessica and I have turned to a subject somewhat lighter of heart.

From the likes of urban homesteaders, artisans, D.I.Y.-ers, and hobbyists of all stripes, brilliant handiwork is all around us. We are in constant admiration of the power of one’s own two hands, and the good deeds they can do. And for the perfect symbol of a handmade life infused with joy and meaning, we’ve handed the microphone to Elizabeth Zimmermann:

One tends to give one’s fingers too little credit for their own good sense.

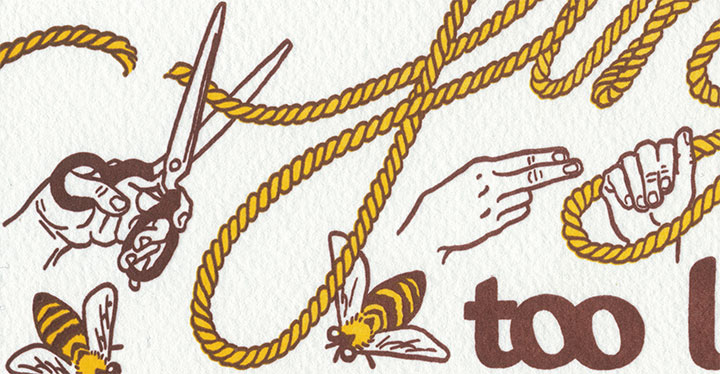

Now, as many of you probably know, Ms. Zimmermann was a knitter (that’s an understatement; I’d say more like All-Time Super-Queen Knitter of the Cosmos, Forever and Ever, Amen). But like every knitter, there is so, so much more to her than that. So rather than simply leaving it at yarn and wool, we discovered a cornucopia of the pursuits that fingers like to turn to when they’re not knitting. There are no idle hands here, to be sure.

Just in time for the fall harvest and in cozy preparation for the winter months ahead (or for our friends in the southern hemisphere, looking forward to a fruitful summer), Get Handy overflows with simple pleasures and home comforts. Elizabeth drafts a cable pattern and whips up a Fair Isle yoke. A little slow food takes root in the garden. Honeybees guard a new crop of candles. Fresh home-canned treats stock the shelves. Chickens scratch along a fence of golden (darning) eggs. Over a cup of tea, puzzles piece together and checkers crown kings. And when they’ve put down the yarn and scissors, the hands spell it out for you in American Sign Language.

Oh, and the Tailor’s blueberries and Jessica’s dilly beans make a cameo appearance. Yum.

A portion of the proceeds from Get Handy will be donated to the amazing healing hands of Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders, via Tricoteuses Sans Frontières / Knitters Without Borders, which organizes knitters to raise funds for MSF/DWB. MSF, winner of the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, is a medical relief organization dedicated to assisting people in distress around the world.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Get Handy: No. 10 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 158

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is hand-colored and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Elizabeth Lloyd-Jones Zimmermann (1910 – 1999) was a British-born master knitter. EZ (as she was known by legions of knitters) moved to the United States and founded Schoolhouse Press in the 1950s, teaching a new approach to knitting through original designs, newsletters, books and a television series. Her no-nonsense approach was laced with humor and readily applied to life beyond knitting, from encouragement in experimentation to trusting one’s own instincts. Americans were reintroduced to the easier, faster German or Continental style of knitting, which had fallen out of favor during WWII, while EZ encouraged students to think on their own using EPS (Elizabeth’s Percentage System) to easily size garments. EZ’s daughter Meg had continued her knitting legacy, most likely inspired by her mother’s motto: “Knit on with confidence and hope, through all crises.”

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

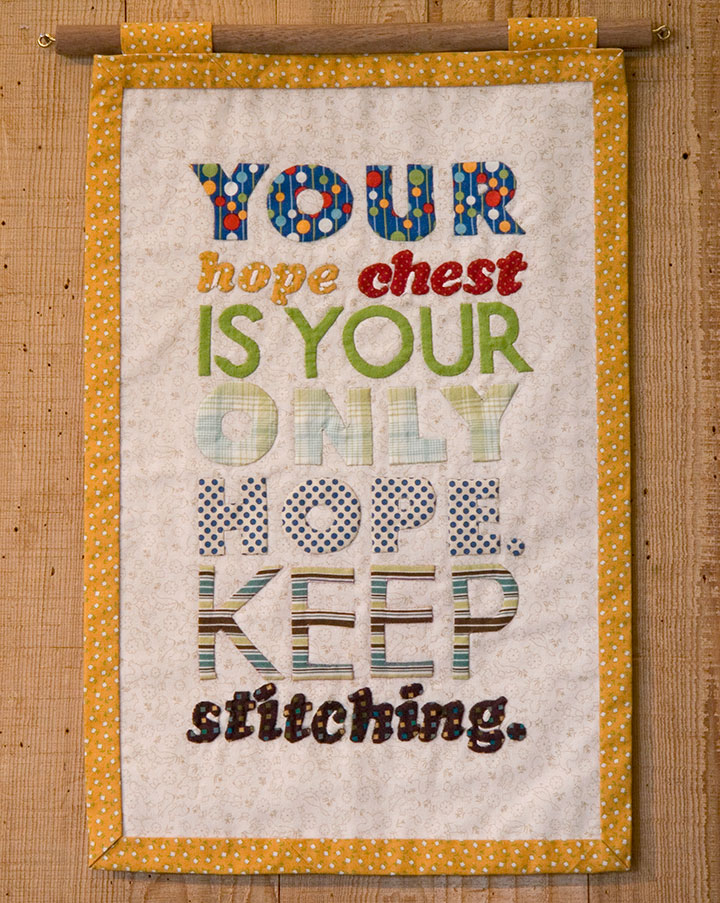

October 16th, 2010

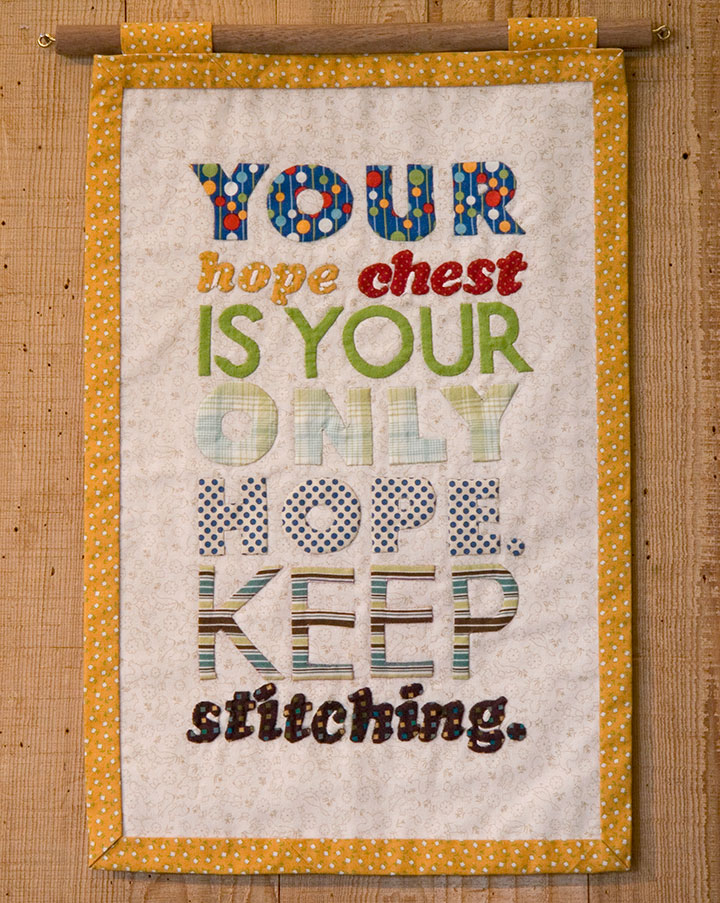

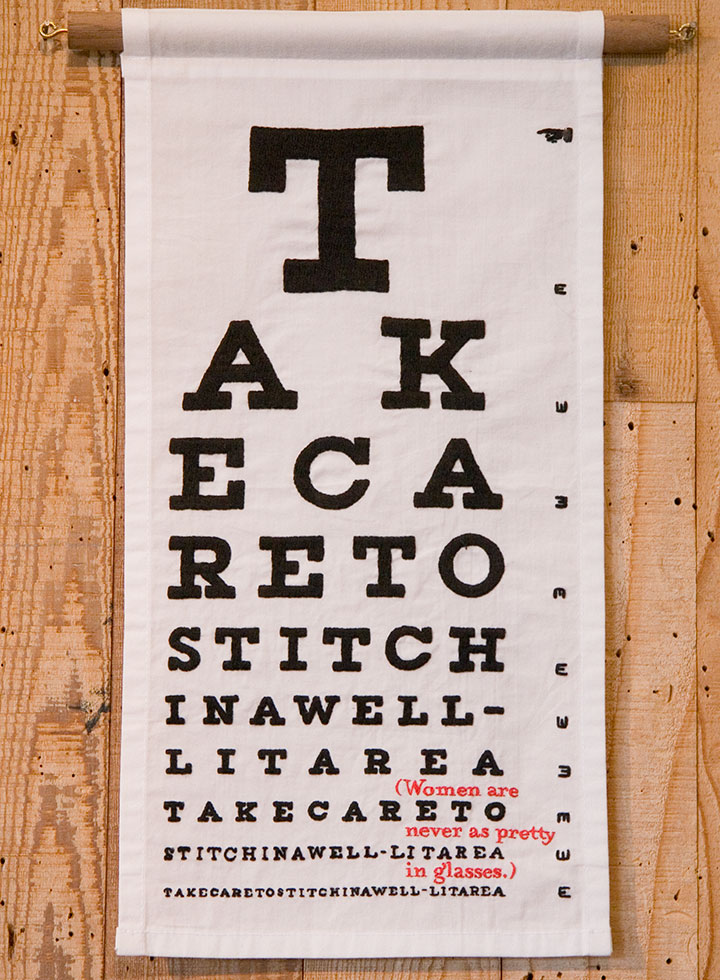

By now you’ve figured out that I have a thing for stitched lettering; and since I’ve already rambled on ad nauseum in the last post, I can keep this one a little shorter.

And anyway, I somehow neglected to take any process photos for two of these. Oops.

The knitted broadside was such a success that I decided to try branching out into other textile media. For Broadside No. 4, I took a shot at appliqué—something I’d never done before. Hand-sewing all those fiddly little pieces of fabric ended up being just as daunting as cutting a steek.

The hard work was oddly fitting for the concept: historically, a traditional wedding trousseau would have been sewn by a girl or young woman, in hopes of one day becoming a married woman with a home of her own. By the time she reached young adulthood, a woman would have spent years creating dozens of hand-sewn garments, household linens and other useful textiles, all gathered and stored in her “hope chest,” awaiting the day she would become a bride.

The thing is, back in the days when women couldn’t vote, or own property, or head a household, marriage was a woman’s only shot at independence or social status. (Hence the snark.)

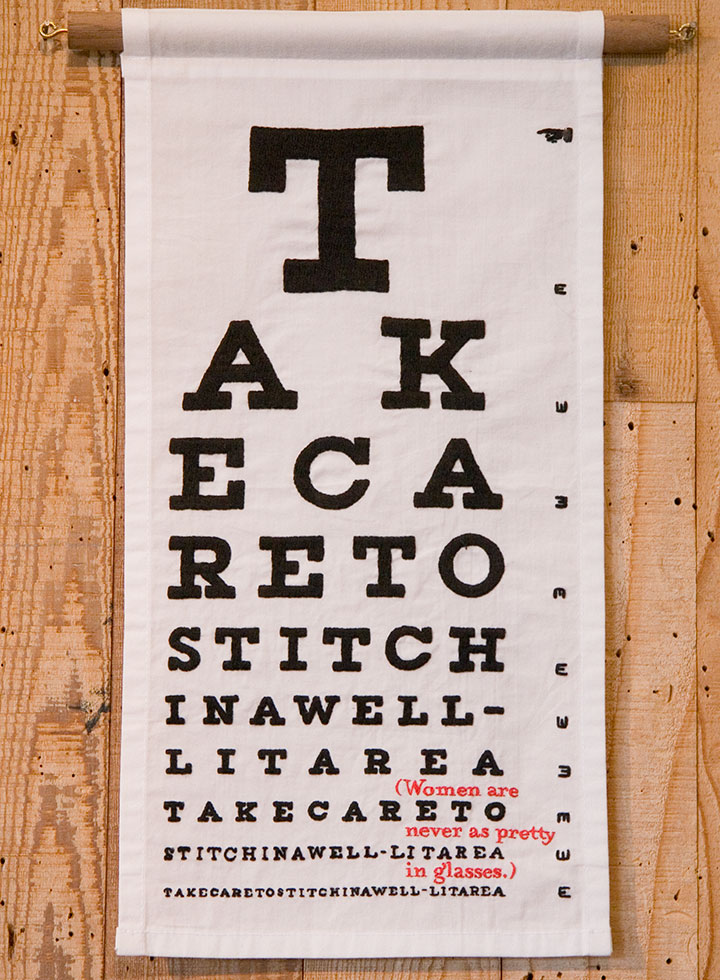

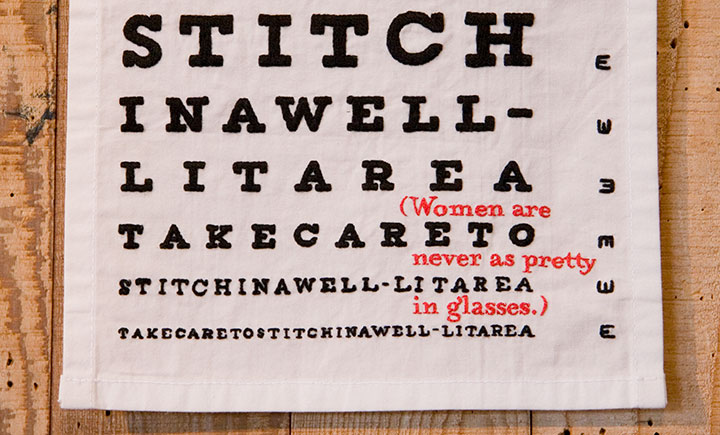

For the others, I turned to the original, old-school ancestor of fabric paint: embroidery. The method fit the madness this time, too, as I spent what seemed like a century hunched over and squinting, hand-stitching an eye chart…

…complete with something to read between the lines.

This one gets personal. As a glasses-wearing gal myself, I happen to disagree with the statement—but I’ve actually heard these very words spoken by a woman. She wasn’t wearing glasses.

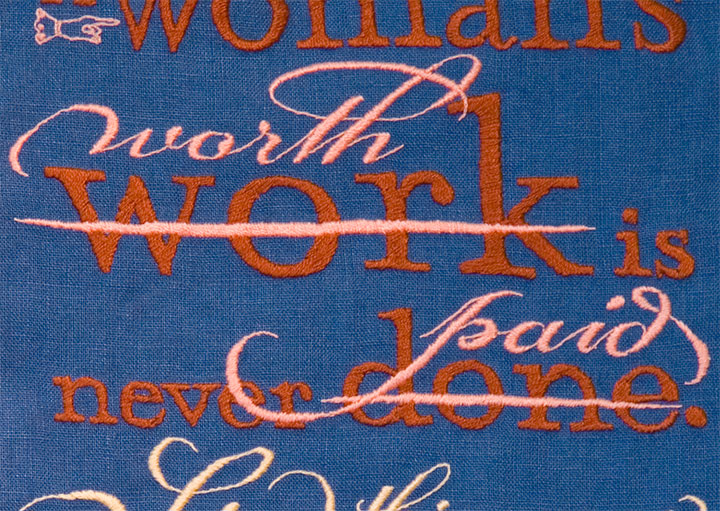

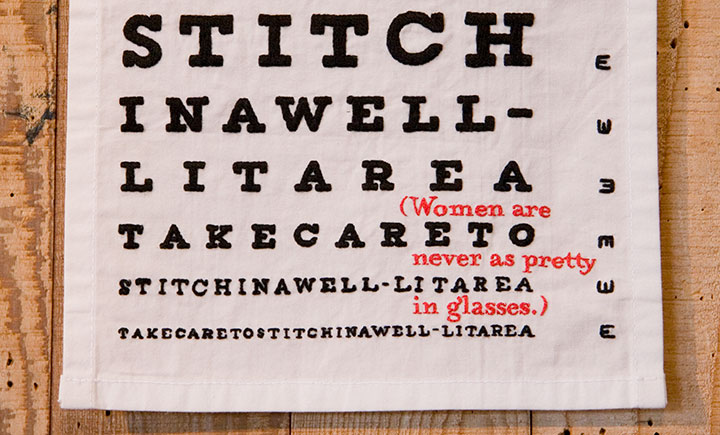

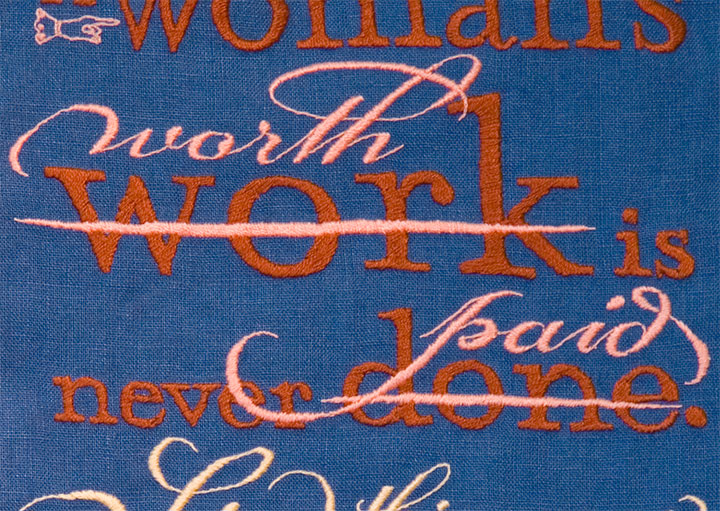

Last of all, I got to thinking about how men who sew for a living are called tailors—and women who do the same are called seamstresses. And how the two terms don’t quite add up to the same meaning.

Despite what the scornful quipping of the text might indicate, I had the most gleeful fun with this one. Unlike knitting, which confines the designer to a grid, or appliqué, which can only push the detailing so far, embroidery has almost limitless possibilities. So I went nuts with the tails and ligatures and dingbats, simply because I could. I love that about embroidery—it’s as flexible as I need it to be, and as fluid and crisp as the printed page.

All that was required was the patience to work each letter by hand. But it didn’t feel like patience—it felt like meditation.

It’s surprising how easy it is for embroidery to mimic letterpress. And watching “wood” type pop up from the fabric, rather than punch into paper, is a mighty satisfying sight.

Uppity notions aside (no pun intended), the Women’s Work broadsides are a fun way to slow down and take a break from what I normally do in the studio. But as I wrap up each one, I find myself hankering to get back into the print shop. By comparison, setting type and drawing letters suddenly seems like speedy work!

October 11th, 2010

While I’ve been hiding away, wrangling my 900-pound gorilla, Jessica has been cooking up something pretty great.

Thanks to her hard work and the wonderful Brian Hutcheson‘s invitation, we are pleased as punch to announce our first-ever dual exhibition!

Feminist Wiles: Jessica Spring and Chandler O’Leary

Now through November 5

Ted Sanford Gallery, Charles Wright Academy

7723 Chambers Creek Rd. W

Tacoma, Washington

Open 8 to 5, Monday through Friday

It seems weird that after more than two years of collaborating, giving lectures and printing in the street, we’ve never had an honest-to-goodness show together.

But when Brian offered us a cavernous space, his help with installation, and the chance to indoctrinate the innocent introduce our series to the kids at Charles Wright—well, we’d be nuts to pass that up.

For the first time, all nine (and-a-half) Dead Feminist broadsides to date, plus our two steamroller gals, are on display together.

We also have a little mini-exhibit about our process,

and lots of little goodies to introduce people to letterpress.

Jessica and I have rounded out the collection with solo work that complements the theme of the show. Jessica’s half consists of Do You Feel Beautiful?, a series of broadsides featuring famous aphorisms on beauty. Here’s the thing that blows my mind into tiny pieces every time I think of it: the quotes are letterpress printed on the pages of a Braille edition of Seventeen magazine. Whoa.

I contributed Women’s Work, an ongoing series of broadsides created in hand-sewn textiles rather than my usual letterpress.

Now, I get a ton of questions about these things whenever I show them, so I thought I’d outline the ideas and process behind them here.

The Tailor first sparked the idea for the series; as you know, he makes his own clothing (hence the nickname). This is a feat that never ceases to amaze me, and I’m not the only one—he gets a lot of comments, usually along the lines of “Wow, you made that?” He’s always a little surprised by these comments, because where he grew up, a lot of people (including his family) wore homemade clothing. That got me thinking, though. The people who do all that sewing in the Tailor’s hometown are women—mothers, grandmothers, sisters, daughters, wives. We’re all surrounded and preceded by generations of women who sew clothing, or knit sweaters, or draft patterns from scratch, without any rave reviews—or any comment at all. But every male knitter or quilter I’ve known, every rare and wonderful man who ever picked up a needle, is either looked at like he’s nuts, or treated with reverent awe. It strikes me as a little strange that depending on who made it, and who’s looking at it, a pair of pants can be a work of art—and an actual work of art can be completely ignored.

If you go further back, like, I dunno, throughout the entirety of human history—you’ll find that both men and women have been responsible for creating textile goods in nearly every culture on earth. Yet in almost every case, when men made textiles it was as part of some sort of guild craft or other professional setting. When women made textiles, it was as part of the home front. This is true in every part of the globe, in pretty much every era, going back to the advent of textile technology.

No matter who does the stitching, there’s an enormous amount of technical skill and design sensibility required to make a garment or textile object. So instead of creating divisions and pigeonholes—instead of separating into Art and Not Art, into Man-made and Woman-made, what if we started seeing the inherent worth in the objects themselves? And what happens when we take a handmade textile and stick it in a gallery? Does its perception change?

Based on what I’ve seen so far with these broadsides, I’d say it does. It’s been an interesting experiment, for sure.

So the Women’s Work series is a bit of an indictment of the double standard, and while the snark is aimed at a wider target, I wrote them as if I were speaking to a woman. Each one is completely made/knitted/sewn/pieced/embroidered/etc. by hand, from design to pattern to construction. The text reads in the voice of a disapproving female role model (or the insidious voice inside our own heads)—in the tone of the backhanded compliment, the cheerful put-down. Each is also designed in the style of a traditional letterpress broadside, to put the typography within the context of an art form centered around mass communication.

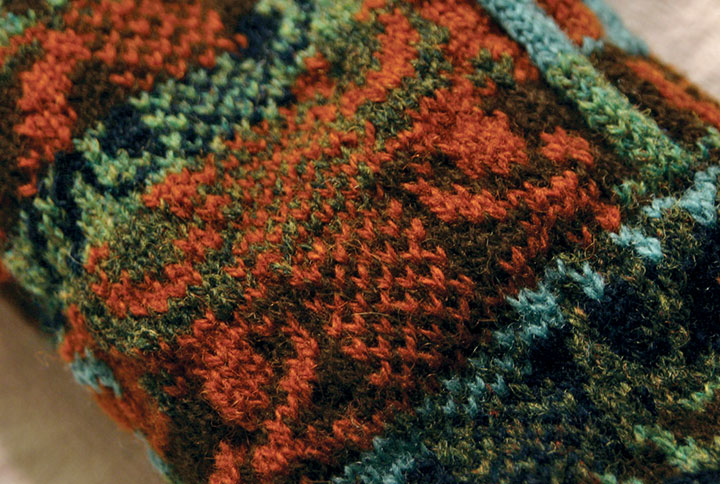

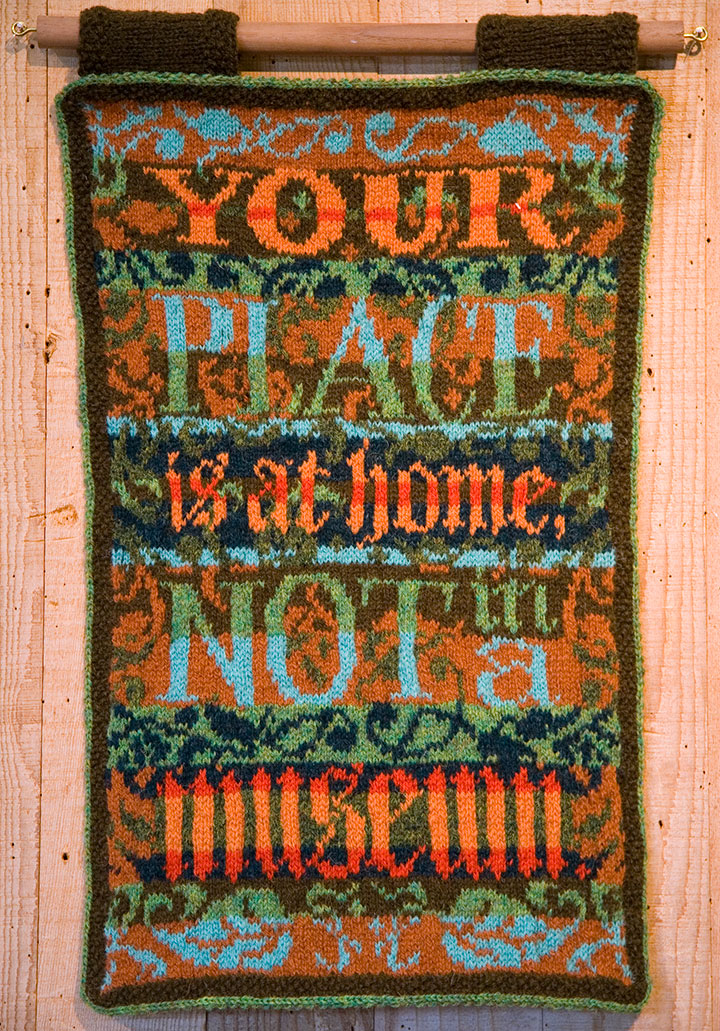

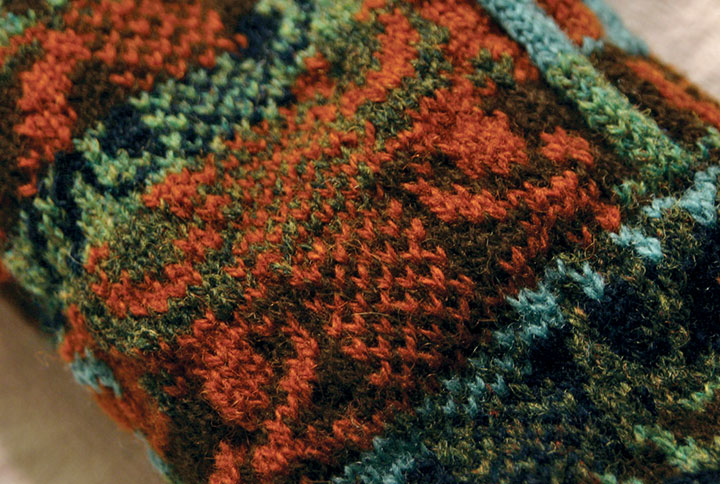

This guy requires a little more of an explanation for folks who aren’t already into wool.

This piece, made almost three years ago now, is hand-knitted with Shetland wool, using the traditional Fair Isle knitting technique. Fair Isle—a method practiced since the nineteenth century on the tiny island of the same name, halfway between Scotland and Norway—is a tricky, rather ingenious thing. Traditional Fair Isle pieces are knit with two colors of yarn at the same time; the resulting fabric is durable, extremely warm, and great for any chilly, foggy, wet climate (like, hello, here). Beyond its über-practicality, Fair Isle knitting is simply gorgeous (take a gander at Google). By nature the double-thick fabric is dense and flat, making it an ideal ground for complex patterns and designs—it’s the perfect mix of function and fancy.

Here’s how it works: even though the piece is knitted with two different colors of yarn at once, only one strand at a time ever passes through the needles. The unused strand of yarn is carried loosely, or “floated,” behind the work—which creates a reversed-out image of the design on the back of the piece. It’s the floats that give structure to the fabric, and make it so cozy-warm.

If you were to create a plain ol’ piece of ordinary knitting, you’d proceed from one end to the other of a row, flip the piece over, and work back the other direction. Rinse and repeat. If you tried that with a piece of Fair Isle knitting, working the “wrong” side would be extremely difficult, since the floats would now be facing you and covering your stitches. Now comes the tricky, smarty-pants part. Flat Fair Isle pieces are first knitted up into a big round tube, and then cut to lie flat. When you knit in the round, you never encounter the wrong side of the work. You just spiral around and around on the right side, happily knitting away and floating the unused color behind you as you go.

So in this case, once I had drafted my design into a gridded stitch pattern, I just pretended I was knitting one really big sleeve (or a neck warmer for a giraffe) with really teeny needles.

Ah, but remember the operative words above: you have to cut the piece to finish it. I had never done this before, and let me tell you, there’s an awful, terrifying finality to the idea. Torn sweaters unravel. Snagged socks fall apart. Who in their right mind would cut a piece of knitting on purpose? And even if you could do it, what happens if you make a mistake? Once you make that cut, you’re done.

This is where the true brilliance of the technique hit me like a ton of bricks. The Scotswomen of Fair Isle are a breed apart—and so are their sheep. Shetland wool, the material traditionally used in Fair Isle knitting, has a magical property that makes this crazy notion work: each wool fiber is covered with microscopic scales that attach to one another. Because the wool sticks to itself, the stitches become slightly matted as you knit. So following the Fair Isle method, you work a little buffer zone called a steek (see the checkerboard strip above?) into your design, and then cut right down the center of the steek. If you use trusty Shetland wool, your stitches won’t unravel when you cut them.

At least, that was the theory. I didn’t quite believe it at the time. But I’d come this far—I didn’t want to lose faith. (If you’re looking to try Fair Isle knitting yourself, I find a glass of wine helps.) So I took a steadying swig, held my breath, and cut.

And then I exhaled. And blinked. I had a flat piece. Gingerly I tested the cut edge—and was amazed. Even with a fair bit of tugging, the stitches refused to unravel.

I will never question a Scotswoman again.

My favorite thing about all of this, beyond the magic of Fair Isle itself, is that knitting really lends itself well to letterforms. Even though the pattern is drafted out on a grid, the forgiving nature of knitted stitches turns every square on the grid into a slightly curved, irregular shape. So when you zoom out and look at the piece from a distance, those grid “pixels” turn into nice little serifs, curves and curlicues.

The rest of the broadsides in the series are made using other types of needlework (more on that in the next post), but the knitted piece is still my favorite. I think I need another dose of that Fair Isle magic in my life—maybe next year you’ll find me up to my knees in wool again.

(Read about the rest of the “Women’s Work” broadsides in part two.)

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)