March 16th, 2015

It’s been more than four years since my last artist book (which, incidentally, I’m still working on)—I guess it’s been that long since I had something to say that warranted a multi-page art format. I suppose when it rains, it pours, though—because with this new project, there’s so much to say that an artist book can’t quite contain it all. This project has got words and images spilling out of me every which way. So fair warning: this is going to be a long post. There’s a lot to show you, and a lot to explain; there’s really no way to tell you this story without telling you all of it.

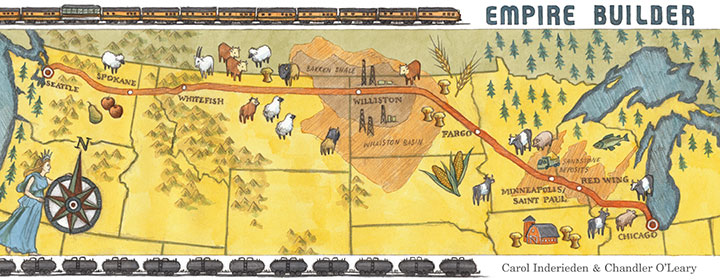

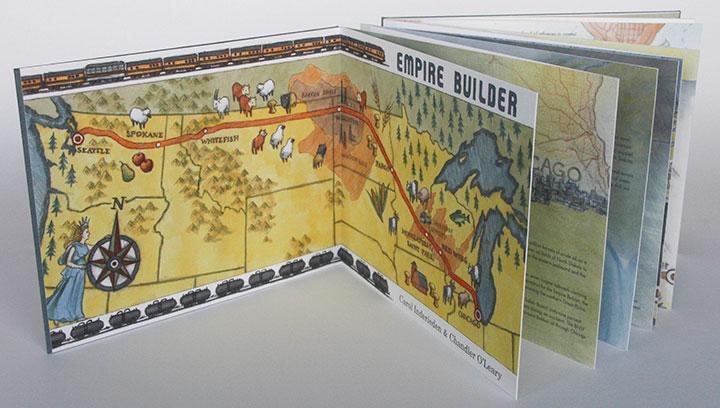

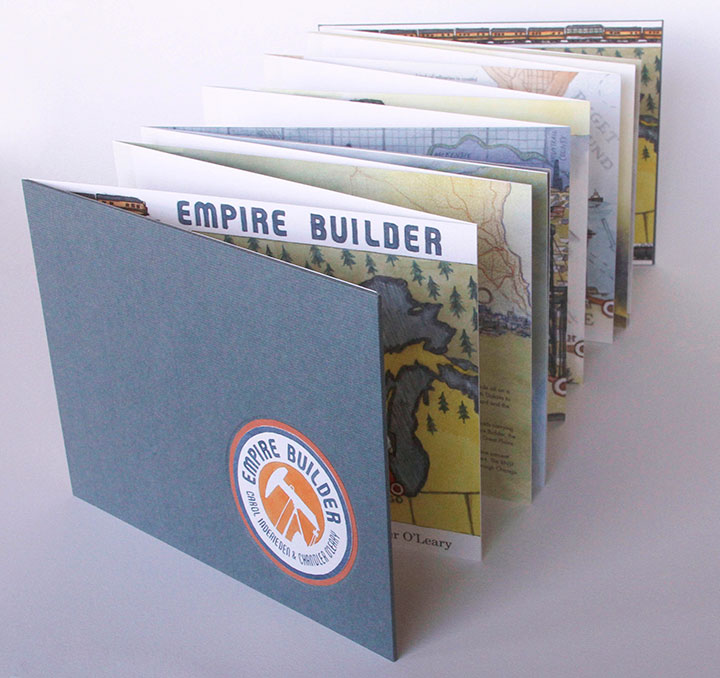

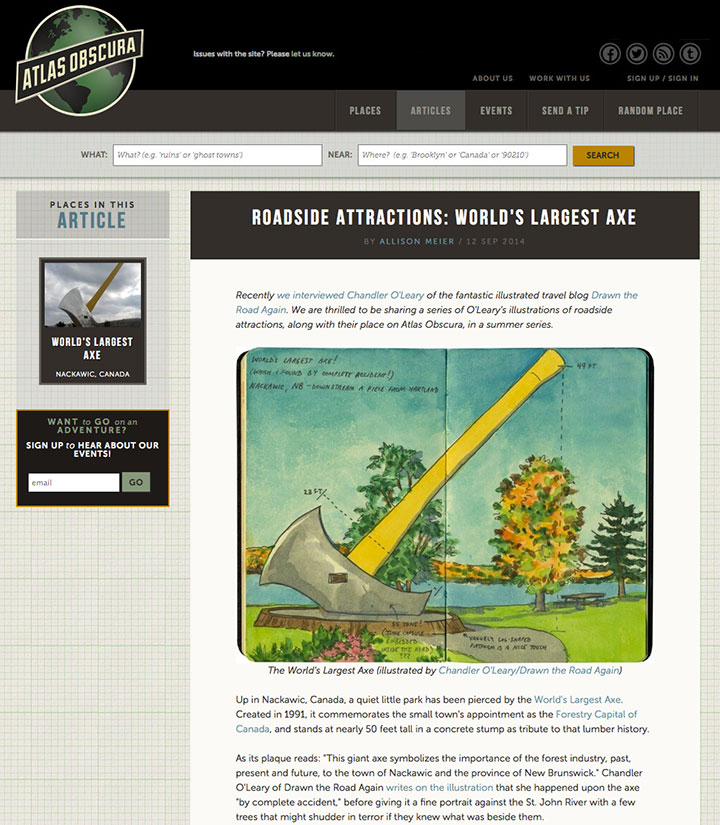

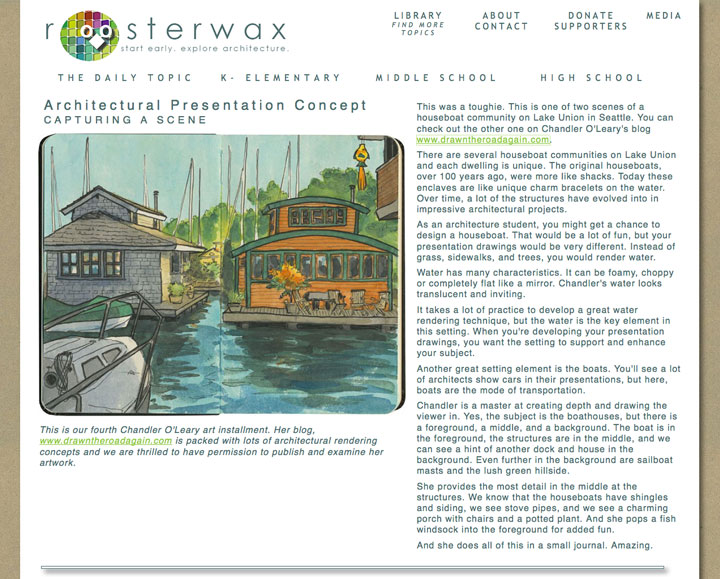

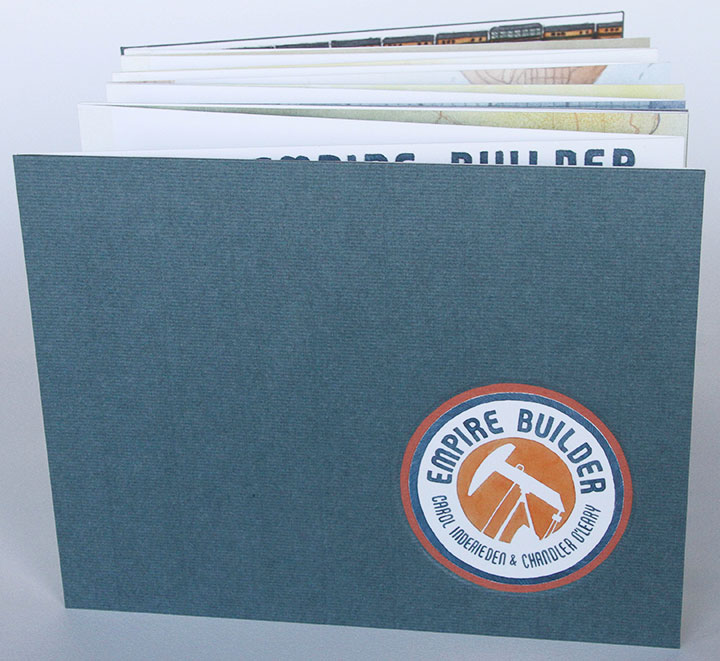

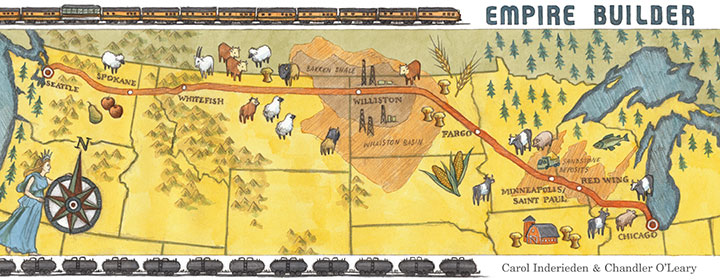

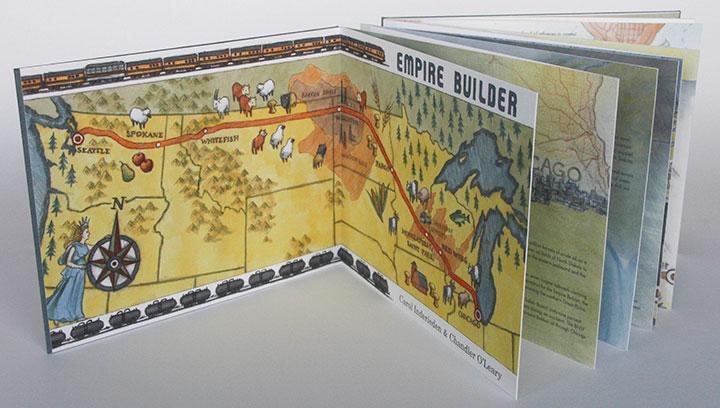

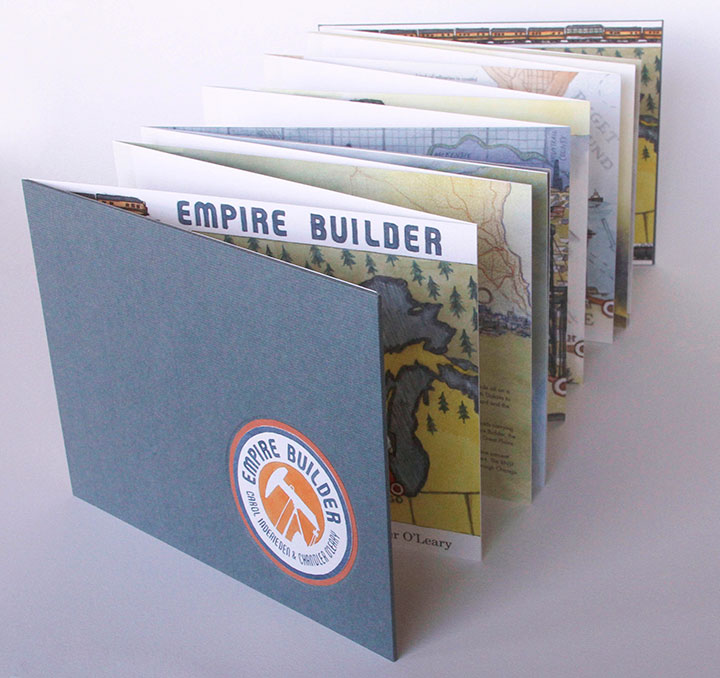

Before I get too far into it, though, I’ll give you the short version. Pictured above is my new artist book, entitled Empire Builder. It’s a collaboration with my friend Carol Inderieden, who is also a writer and illustrator. The book is about oil—that controversial new hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) process, to be precise.

(If you want to stop reading now, I’ll understand. But if you’re stouthearted enough for a lot of backstory, let’s dive in.)

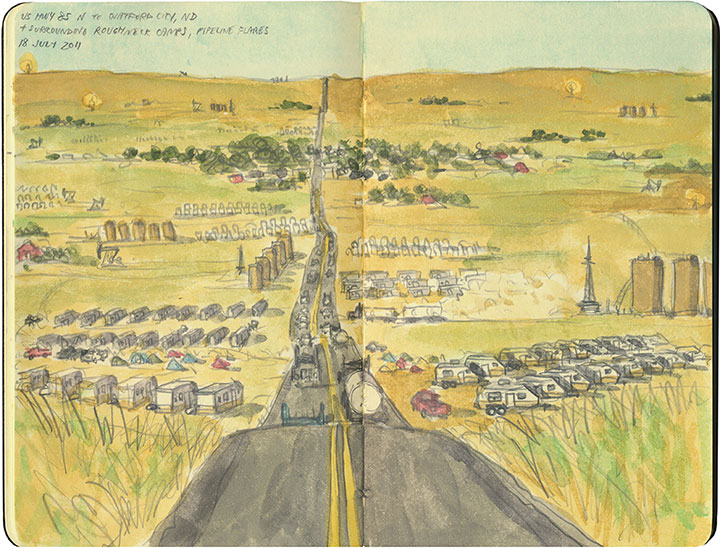

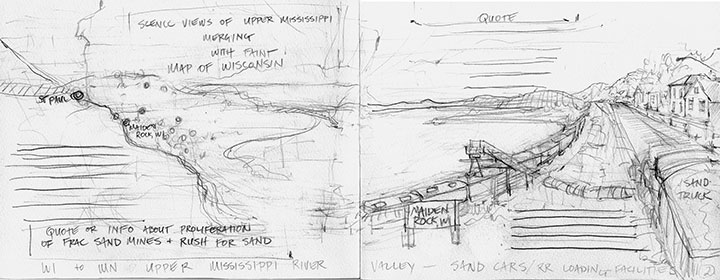

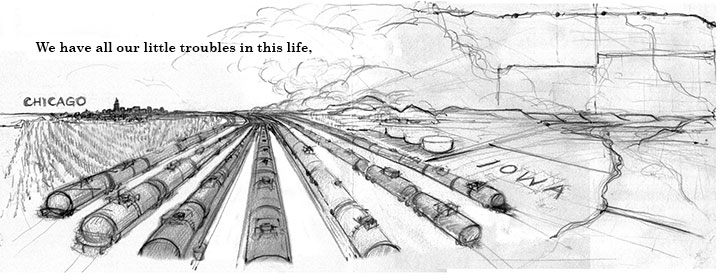

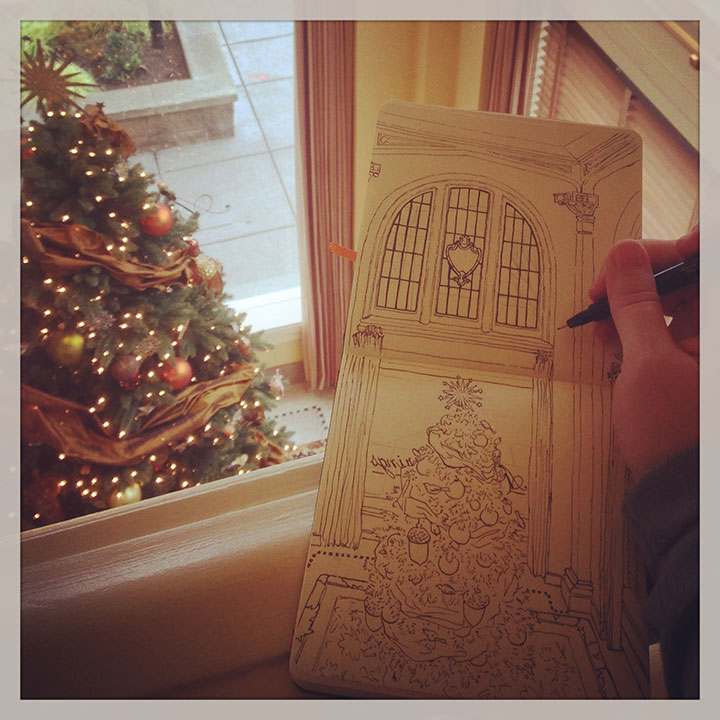

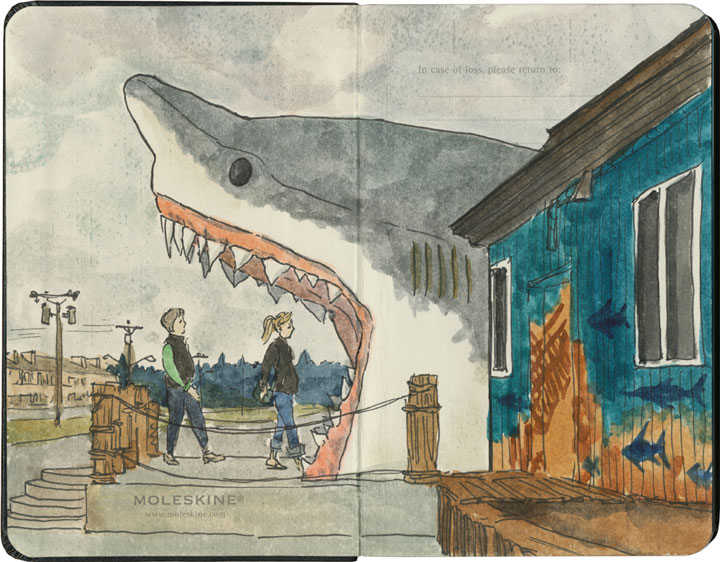

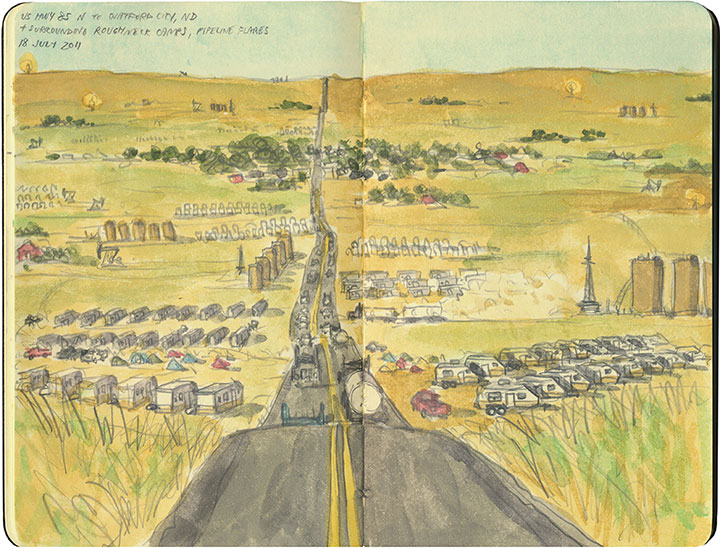

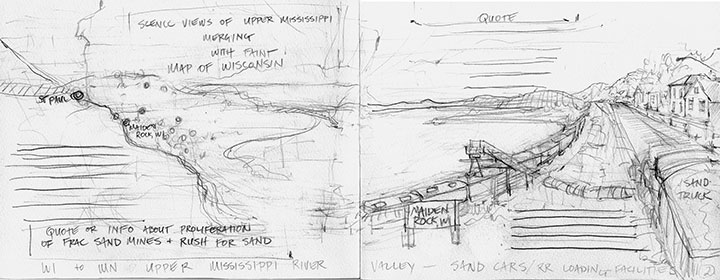

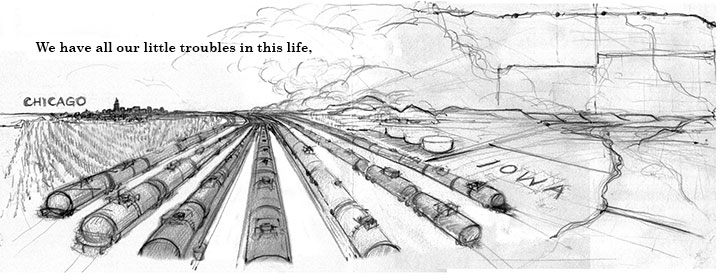

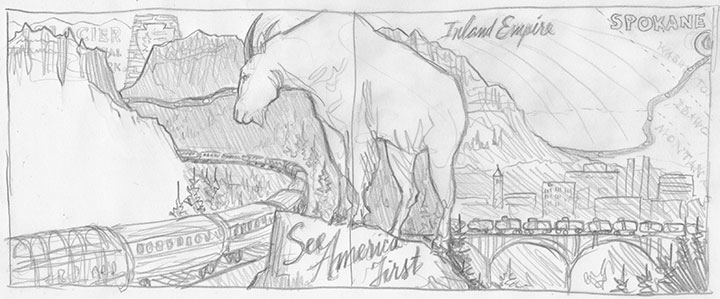

For me, it all started with this sketch.

The Tailor and I were in the middle of a cross-country road trip in 2011. One of our planned stops was Theodore Roosevelt National Park in western North Dakota. That part of the state was an old haunt of mine (I lived in North Dakota for several years), and I was excited to show my spouse a place I knew so well—or at least, I once knew. When we got there, I was utterly unprepared for how quickly and drastically the place had changed. I knew the oil boom had begun there, but I had no idea I’d find the landscape almost unrecognizable.

The once desolate highway was nearly at a standstill with traffic. Every hillside was occupied with RV camps and oil platforms, all built around the process of extracting crude from the Bakken Shale below ground. It was the end of the work day, so there were people everywhere—and we felt conspicuous with our out-of-state plates and tree-hugger-model car. Needless to say, I didn’t feel comfortable taking photos with my giant (and not at all discreet) camera. So instead I pulled out my sketchbook and jotted down the scene, right there in the moving vehicle, while the Tailor drove. It’s the only image I captured of the oil fields, but I still look at this and remember every detail of that afternoon.

A little later I was relating the story to Carol, and she knew all too well what that day felt like for me. Carol lives in western Wisconsin, in an area called the Driftless Region—so named because unlike the lands surrounding it, the area was never glaciated during the last ice age. So Carol’s neck of the woods has a dramatic beauty to it, with deep valleys, swift rivers and sheer cliffs—a landscape very different from the rest of the state (this is her photo, by the way). The Driftless Region is also unique in that the bedrock there is rich in silica—something that has suddenly become extremely valuable to the new oil industry. Carol explained to me that in the past few years, oil companies have been buying up farmland in her area for strip mining, and excavating huge quantities of silica-rich sand for use in the frac drilling process in the Bakken oil fields. What I glimpsed in one afternoon in North Dakota, my friend has watched unfold on a daily basis, right in her back yard.

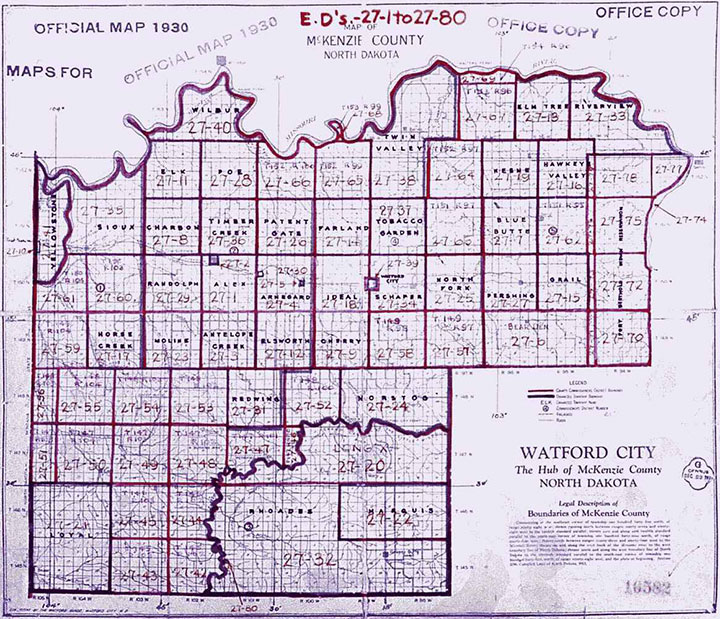

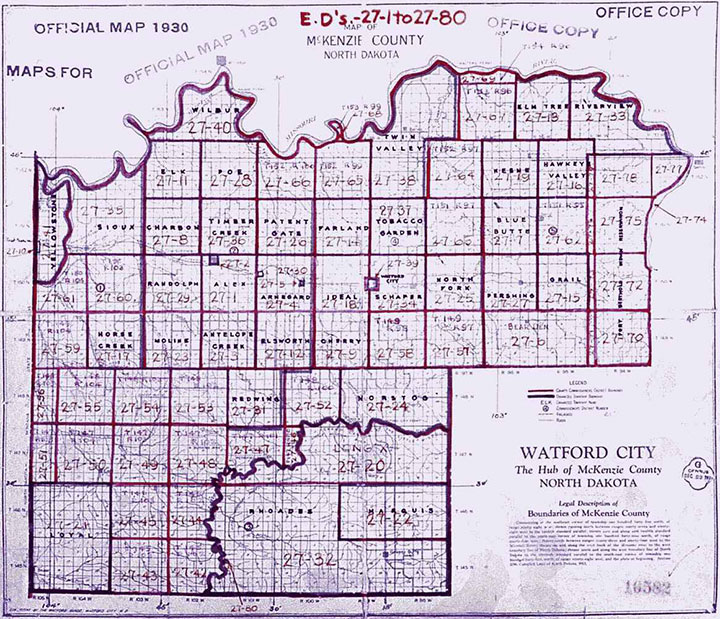

Her story, and what I saw in North Dakota, reminded me of what I’d read about the pioneer days—of dramatic land grabs, of politicians carving up maps of regions they’d never see in person, of arbitrary grids imposed on wild landscapes.

Anyway, fast forward a few months more, and I start seeing local newspaper stories about Bakken crude oil trains arriving in Seattle and Tacoma in huge numbers, and how devastating a derailment, spill or explosion here could be. All of a sudden, the fracking industry was in my back yard as well—not just some faraway place I happened to have personal memories about.

So I did what I always do: I started thinking about how I might turn my thoughts into an art piece. I called Carol and asked her if she might want to collaborate on a project about all of this. It wasn’t long before we decided on an artist book—which would end up taking us on a two-year odyssey before it was finished.

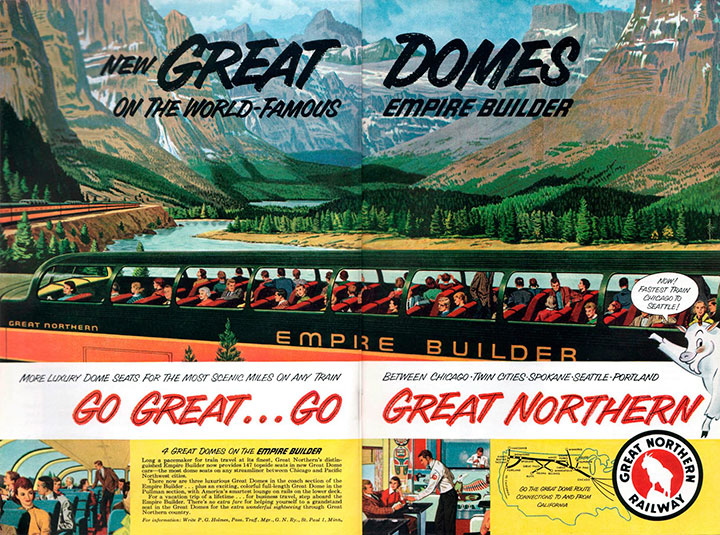

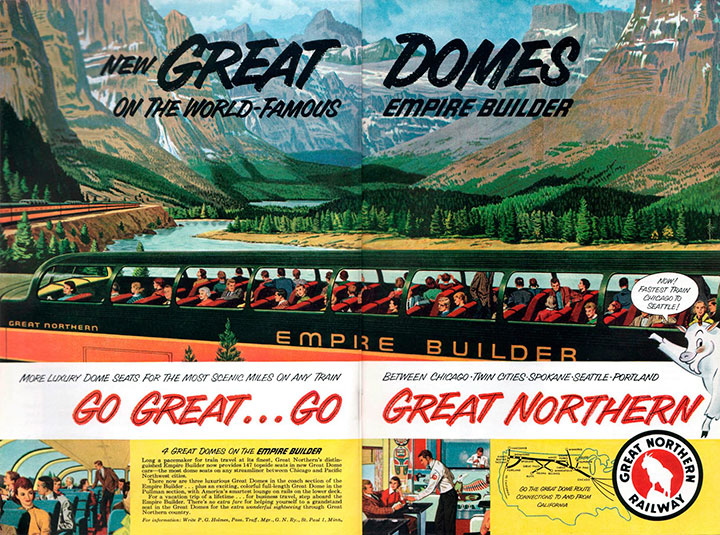

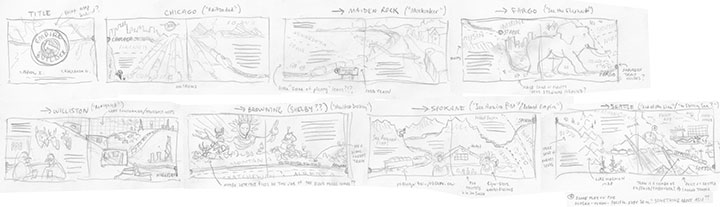

We wanted to link these three regions (the Driftless Area, the Bakken Shale, and the Pacific Northwest) together somehow for our book, and we had a perfect, ready-made means by which to do so: the railroad. Not only was there a train that stopped in all three places (and both Carol and I have traveled on that train), but we soon learned that the entire supply chain for the frac industry followed the path of the Empire Builder railroad line, from Chicago to Seattle. We couldn’t believe how perfect it was.

The railroad ended up becoming the backbone of every part of our book: concept, historical framework, even physical structure.

Whenever we weren’t sure what to do, the railroad brought us back to center, and kept our sequence in order.

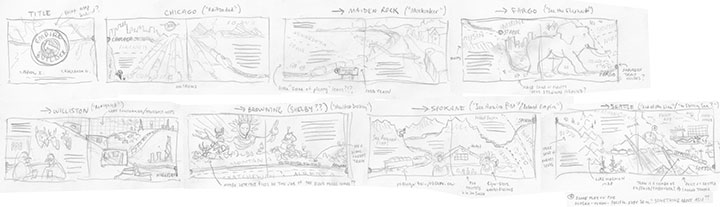

What proved to be more difficult was just which story to tell within the pages. As you can see by this already out-of-hand blog post, we had a lot to say, and we couldn’t possibly say everything. We didn’t just want the book to be a 20-page rant on our feelings about the environment, nor a didactic explanation of how the frac process works. We wanted to show, rather than tell. We wanted to make our readers fall in love with these landscapes as we have. We wanted to provide evidence of the consequences of the oil boom. And we wanted to create a tangible link to history, because all of this has happened before. But our text and images were coming up short; we needed something extra to tie everything together.

Carol came to the rescue, by finding a short quote that embodied the mood we wanted to get across. It added an air of foreboding to the piece, and it worked perfectly with all the allegorical images we were throwing around. And here’s the wacky thing: the quote is from the New York Times. In 1861. And it fits so well with what’s happening now that it easily could have been written yesterday. Here’s the quote:

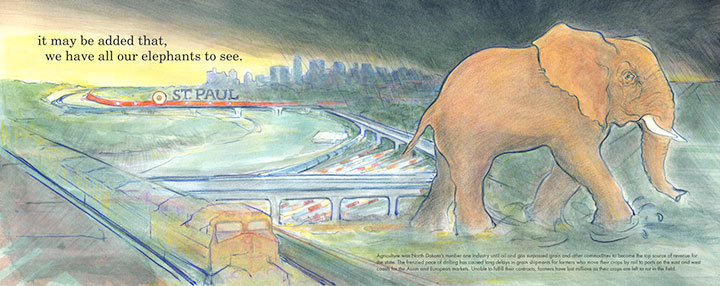

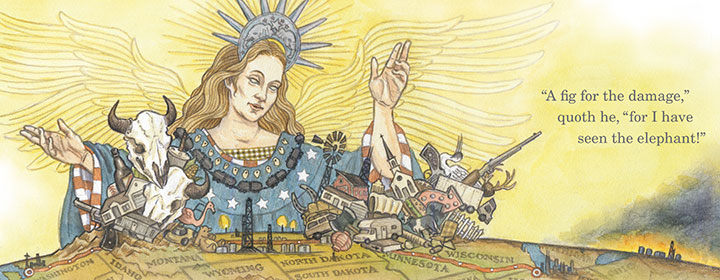

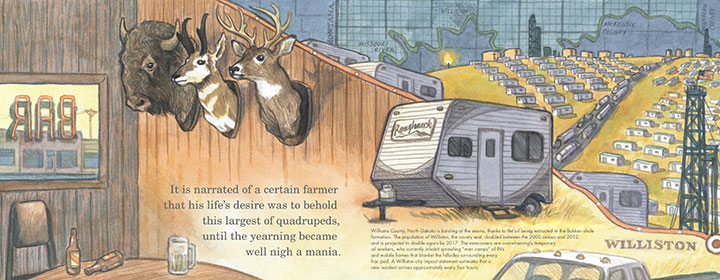

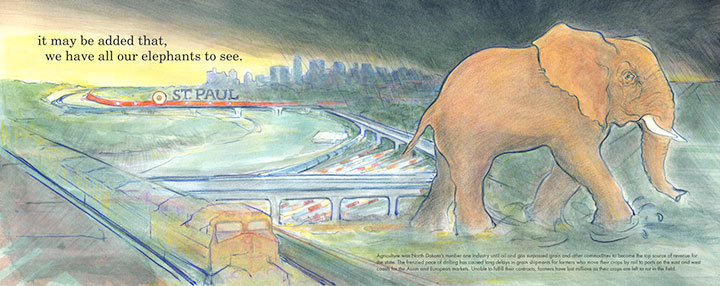

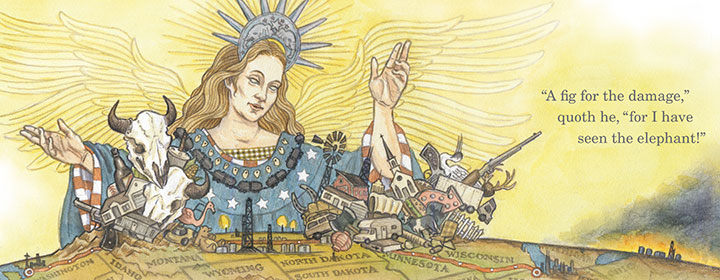

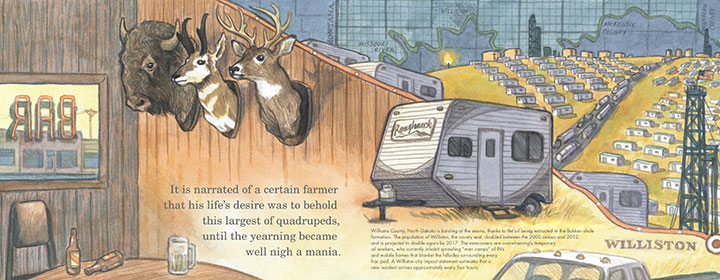

We have all our little troubles in this life, and for those who are not too proud, to use a popular phrase, it may be added that we have all our elephants to see. It is narrated of a certain farmer that his life’s desire was to behold this largest of quadrupeds, until the yearning became well nigh a mania. He finally met one of the largest size traveling in the van of a menagerie. His horse was frightened, his wagon smashed, his eggs and poultry ruined. But he rose from the wreck radiant and in triumph. “A fig for the damage,” quoth he, “for I have seen the elephant!”

In the end, we ran the quote in pieces throughout the length of the book—and paired it with illustrations chock full of historical allegory (as well as allusions to old train advertisements, wartime propaganda, and current events). Explaining it all would make this even longer a post than the novel it already is, so I’ll just present our essay at the end of the book to give you the full context behind the quote.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The preceding quote, from an 1861 New York Times editorial, highlights a phrase popular in America during the latter half of the nineteenth century. “Seeing the Elephant” was a figure of speech that came to embody the pioneer experience during the era of westward expansion. To see the elephant was to embark on a quest for riches and prosperity. It alluded to the danger and excitement associated with seeking one’s fortune in an unknown land. The elephant is an illusion, an impossible promise like a desert mirage that disappears as one moves closer. “Seeing the Elephant” later became synonymous with the bitterness and disappointment settlers experienced as they watched their dreams turn to ashes. During this time, the idea of Manifest Destiny — the 19th century notion that Americans possessed the divine right to claim all of North America, by virtue of their moral superiority — was also born and sometimes depicted as the mythical goddess Columbia, leading brave settlers westward.

“Seeing the Elephant” gradually fell out of the vernacular, yet the sentiment endured as the double-edged sword of the American Dream. Evidence of this can still be found in every corner of the West. Prairie homesteaders planted tree claims as a winning bet against Uncle Sam and lost. Tenement families in the East sold everything to migrate westward and buy into the myth of dry-land farming. Wildcat prospectors gambled their lives for oil, silver and gold. Families in the roaring twenties bought on credit, stacking the deck with status symbols before losing it all in the Great Depression. Suburban subdivisions, once symbols of postwar prosperity, have now become outposts of the working poor. The cycle of boom and bust has been resurrected so many times that the Elephant has grown in size from a distant vision to an omnipresent burden, stretching from sea to shining sea.

If the American map were the Elephant writ large, it is the railroad that breathes life into the creature. Throughout the last century of rail development, the anatomical structure of a complex organism has evolved. Today spurs and trunk lines follow a vascular system that carries a lifeblood of raw materials across the nation in a never-ending stream of freight. While the Elephant’s lungs fill with natural gas, its veins run gold with domestic oil and its heart beats ever faster in the Bakken Formation of western North Dakota.

Even in today’s age of dwindling resources and dire environmental warnings, Americans still see the land as a bottomless well to be tapped. In the Bakken, a new frontier has opened and is flooded once again with a new generation of fortune-seekers. “Man camps” dot once-empty hillsides and roughnecks push the region’s infrastructure to the breaking point. Remote rural highways and railroad lines are now choked with traffic. Flames from gas flares and oil slicks bathe the grassland in an eerie, unnatural glow. Yet while the land flows with modern milk and honey, only a few actually taste its richness. Companies grow fat while laborers vie for just a few drops. Communities swell to accommodate the boom, yet risk collapsing as soon as the inevitable bust occurs. All the while, the Elephant still waits beyond the next horizon and Columbia still beckons, just out of reach.

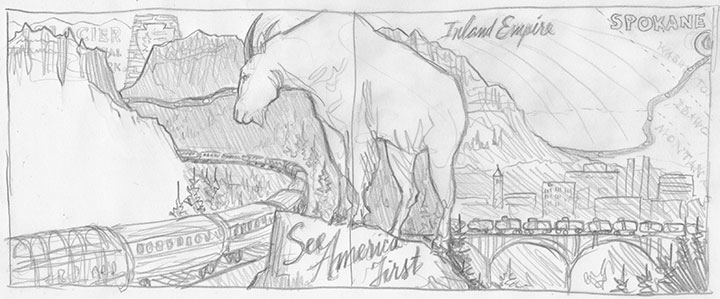

The backbone of the modern Elephant is the railroad line from Chicago to Seattle — incidentally, the same line that carries the Empire Builder passenger train. This train is aptly named for the exploits of James J. Hill, the railroad lumber baron who grew rich transporting timber and other raw materials from the Pacific Northwest to the cities and industries of the Midwest. Today one can ride the Empire Builder from one end of Hill’s domain to the other, and witness every element of the fracking process along the way. In the early 20th century, the Empire Builder encouraged travelers to “See America First” and marvel at the wonders of the natural world speeding past their windows. Today’s rail passengers watch the new Industrial Revolution rolling by.

This book is an attempt to articulate our dismay at the rapid transformation of a West we know and remember. We live and work at opposite ends of the Empire Builder railroad line: Carol in the Driftless Region of Wisconsin, where the bluffs and hillsides are being strip mined for frac sand; and Chandler in the Puget Sound area of western Washington, where Bakken oil is refined and shipped to other ports by tanker vessel. We both have personal ties to the northern Plains, though recent events render the region unrecognizable when compared to our memories. Still, the railroad connects us to each other and the landscapes we love. For the pioneers of the new era, the rhythm of the railroad is the marching song of progress — but for us, it is a lament.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

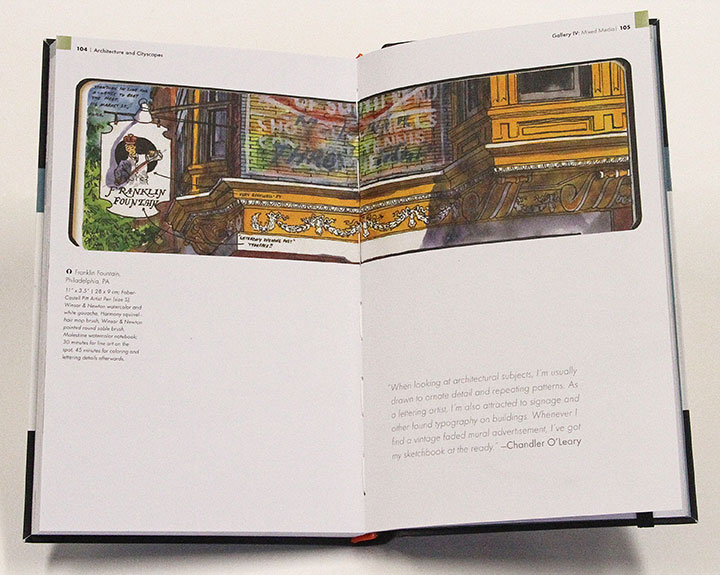

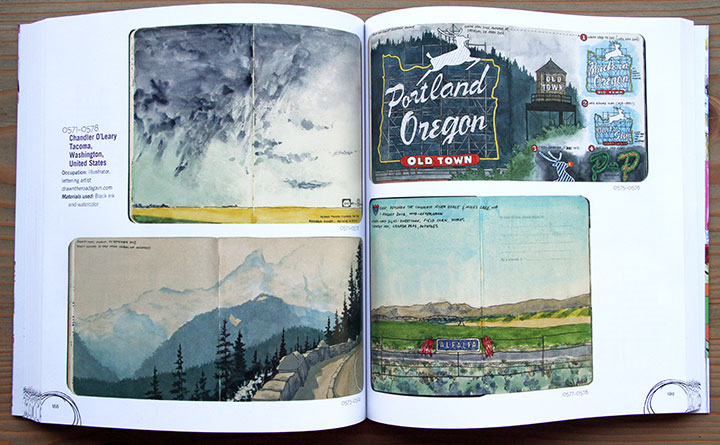

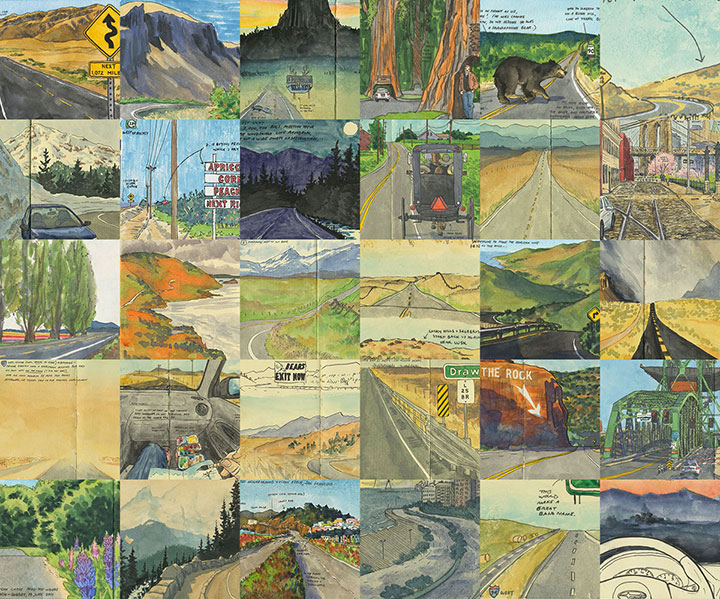

One of the best things about working with Carol on this project is that we both draw—and our aesthetics are not dissimilar. So we could match each other’s style to keep the book consistent throughout—without it being obvious who did which illustration. But that wasn’t the problem.

The problem was that we were originally thinking this book would be letterpress-printed. That would have meant our final illustrations would have to be extremely flat and graphic in style, to accommodate the limitations of hand-printing. This is a mockup I did at an early stage of our “Manifest Destiny” image. I hated it, and I didn’t know why at first. But then Carol and I figured out that what we really responded to was the loose, quick style of the sketch I did in North Dakota four years ago—which mirrored all our process pencil sketches for the book. The letterpress mockup I did above felt too slick, too…”set in stone.” It felt like the wrong medium to convey a phenomenon that is happening so rapidly that even the news media can’t keep up with it.

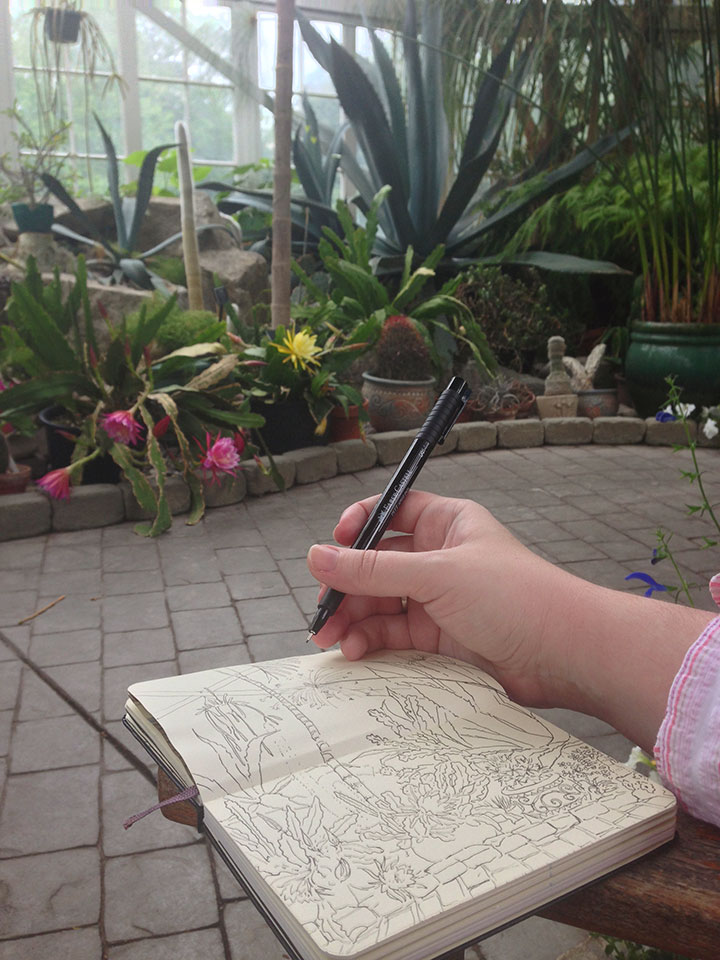

Sketching felt like the right medium—so we changed tack, and made our book a sort of Sketch Storybook instead. We let go of letterpress printing, and decided to digitally print the book—which freed us from all limitations when it came to the imagery.

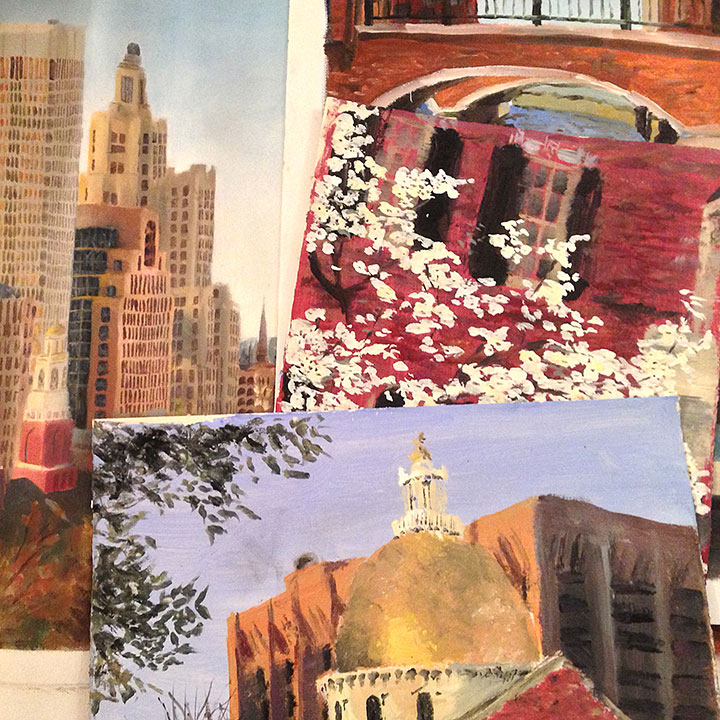

This way, we could preserve the immediacy of our sketch drawings—

—and we could paint in watercolor right on top of our sketches, and reproduce each image in full color (another thing letterpress printing doesn’t allow).

The finished product is an accordion-bound book that reads like a map—tracing both the route of the Empire Builder train and the path of industry and destruction, in one long, unbroken line. When fully open, the book is fifteen feet long.

We printed a limited edition of just 50 books; each one is digitally printed on archival, 100% cotton paper, and hand-bound in hardcover with a paper slip case. Price is $600, plus shipping; we’re taking pre-orders on a first-come, first-served basis, and we’ll begin shipping finished books in April.

If you’d like to reserve a copy, drop me a line at chandler [at] anagram-press [dot] com .

And if you’d like to see the book in person, it’s already making its way around the country to various shows, including a groundbreaking national exhibition on the Bakken oil boom at the Plains Art Museum in North Dakota. Here’s the scoop on where it’s been and where it’s going, so far:

Fifth CODEX International Bookfair

February 8-11, 2015

Craneway Pavilion, Richmond, CA

Bakken Boom: Artists Respond to the North Dakota Oil Rush

Group Exhibition

On display through August 15, 2015

Plains Art Museum, Fargo, ND

CODEX Finds

Group Exhibition

March 24 – April 25, 2015

23Sandy Gallery, Portland, OR

Carpe Librum

Group Exhibition

April 3-26, 2015

Bainbridge Arts & Crafts Gallery, Bainbridge Island, WA

2015 New York Antiquarian Book Fair

Empire Builder represented by the Kelmscott Bookshop

April 9-12, 2015

Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY

5th Annual Puget Sound Book Artists Member Exhibition

Group Exhibition

June 4 through July 31, 2015

Opening reception: Thursday, June 4, 2015, 5:30 to 7:30 pm

Collins Memorial Library, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA

EDITED TO ADD: more shows featuring Empire Builder:

Beyond Brand

Group exhibition

July 30 through September 5, 2015

Opening reception: Saturday, August 1, 2015, 7 to 9 pm

Form + Content Gallery, Minneapolis, MN

The Art of the Book

Group exhibition

June 17 through July 27, 2016

Sebastopol Center for the Arts, Sebastopol, CA

Bridging the Waters

Group exhibition

July 1 through August 21, 2016

Center for Fine Print Research

University of West England, Bristol, United Kingdom

Heavy Metal

Group exhibition

August 31 through October 1, 2016

Berkeley Art Works

Martinsburg, WV

Local Heroes: Book Artists of Washington State

Group exhibition

October 15, 2016 through May 2, 2017

Bainbridge Island Museum of Art

Bainbridge Island, WA

The Illustrated Accordion

Group exhibition

May 5 – 26, 2017

Kalamazoo Book Arts Center Gallery

Kalamazoo, MI

Re-Sisters: Books & Broadsides by Chandler O’Leary & Jessica Spring

Two-person exhibition

February 6 through March 23, 2018

Bryan Oliver Gallery, Whitworth University

Spokane, WA

conTEXT: Broadsides & Artwork by Chandler O’Leary & Jessica Spring

Two-person exhibition

March 3 through April 29, 2018

Antenna Gallery

New Orleans, LA

Rising Together: Artists’ Books and Prints with a Social Conscience

Traveling group exhibition

On view from 2018 through 2021

Fall/Winter 2018: University of Utah Marriott Library, Salt Lake City, UT

Spring 2019: Center for Book Arts, New York, NY

Fall 2019: University of Iowa Center for the Book, Iowa City, IA

Spring 2020: Hoffmitz Milken Center for Typography, ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena, CA

Fall 2020: University of Puget Sound Collins Library, Tacoma, WA (see above)

Spring 2021: San Francisco Center for the Book (in conjunction with Mills College), San Francisco, CA

Frozen Warnings

Group exhibition on the climate crisis

February 1 through May 3, 2020

Bushel Collective Gallery

Delhi, NY

Empire Builder is also now housed in several permanent public collections, including:

– Library of Congress (Rare Book & Special Collections Division), Washington, DC

– Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, Bainbridge Island, WA

– Harvard University (Widener Library), Cambridge, MA

– Miami University Library (Havighurst Special Collections), Oxford, OH

– Minnesota Historical Society Library (Special Collections), Saint Paul, MN

– Newberry Library (Americana Collection), Chicago, IL

– Scripps College (Ella Strong Denison Library), Claremont, CA

– Stanford University (Green Library American History Collection), Palo Alto, CA

– University of Chicago (Special Collections Research Center), Chicago, IL

– University of Connecticut (Dodd Research Center), Storrs, CT

– University of Puget Sound (Collins Memorial Library), Tacoma, WA

– University of Utah (Marriott Library), Salt Lake City, UT

– University of Vermont (Billings Library), Burlington, VT

– University of Washington Libraries (Book Arts Collection), Seattle, WA

– Washington State Library, Tumwater, WA

Save

Save

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)