Blog

September 15th, 2010

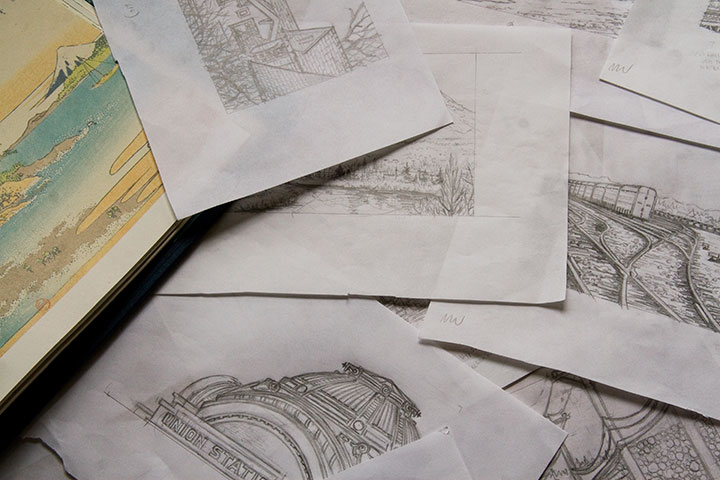

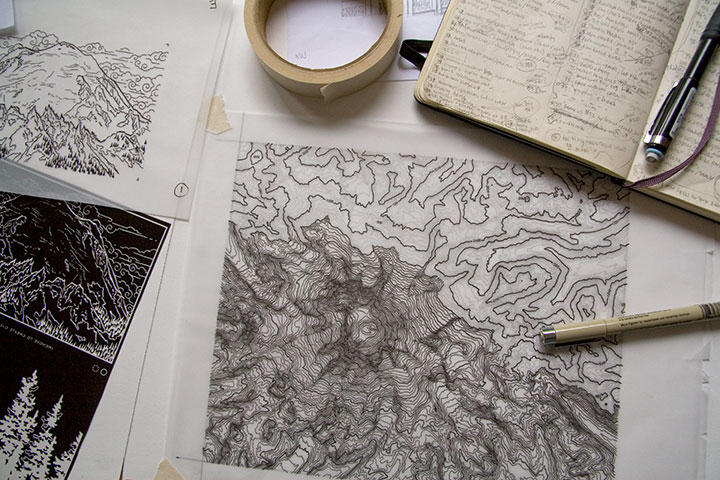

Lately I’ve spent nearly every waking minute of each day with my face an inch away from the drafting table.

Let’s step back, and stretch out a bit.

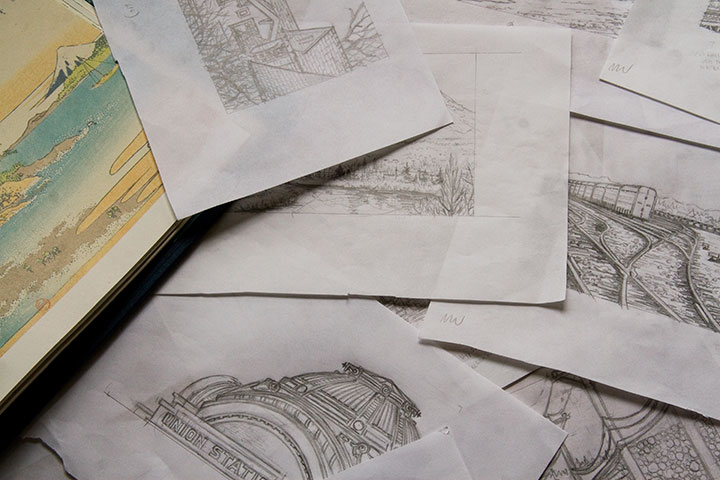

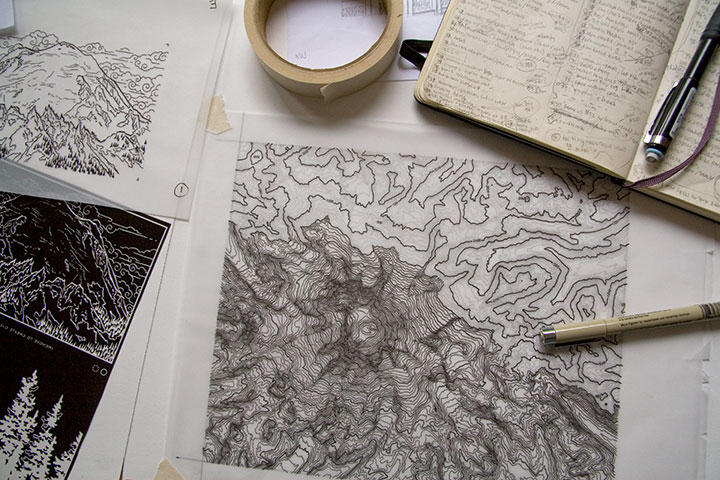

My studio is often a sea of papers—an occupational hazard—but these days the swells have consisted of pencil snapshots for my Mt. Rainier book. Dozens, and dozens, and dozens of them.

Time is ticking down, counting closer and closer to zero, and there are still many miles to cover before the clock strikes deadline. Yet suddenly, things are starting to come together. It won’t be long until I can share something that makes sense—something that looks more like a book, and less like a pile of drawings. I promise that you’ll be among the first to see it when I do.

But if I go missing for long stretches at a time—well, you know where to find me.

August 21st, 2010

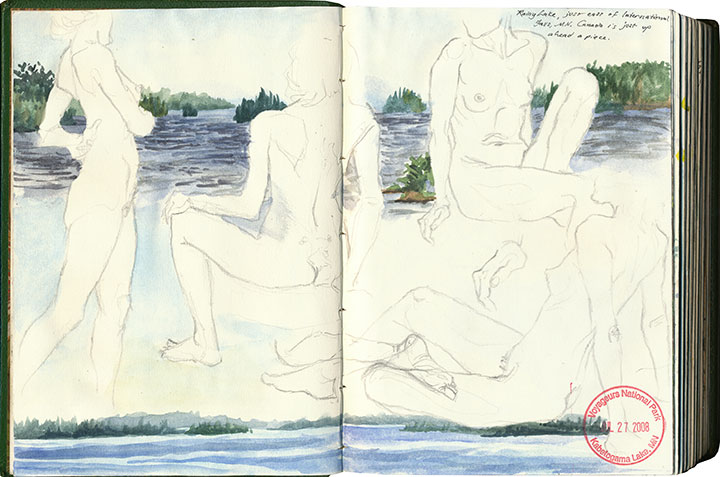

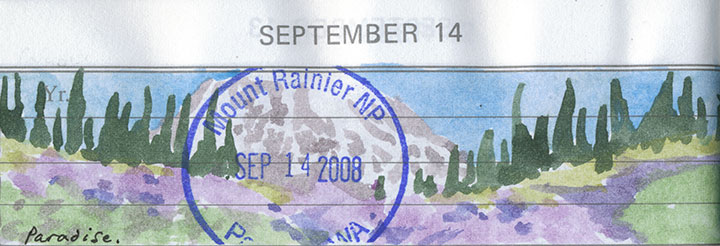

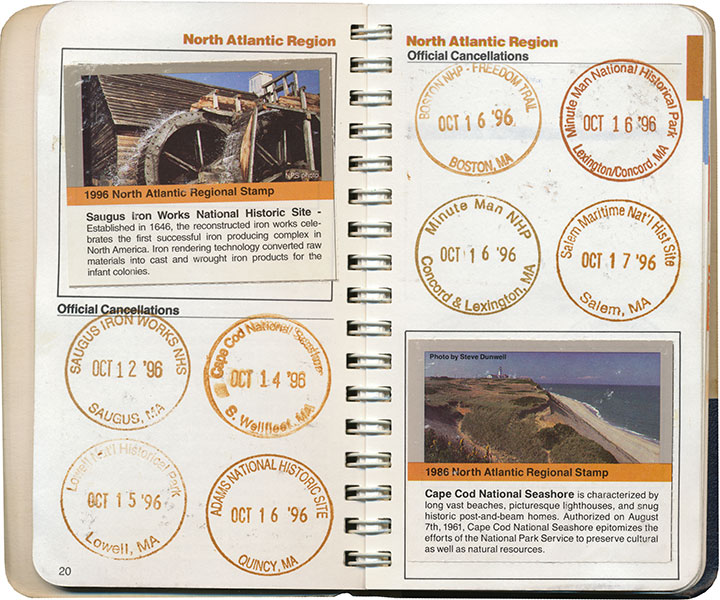

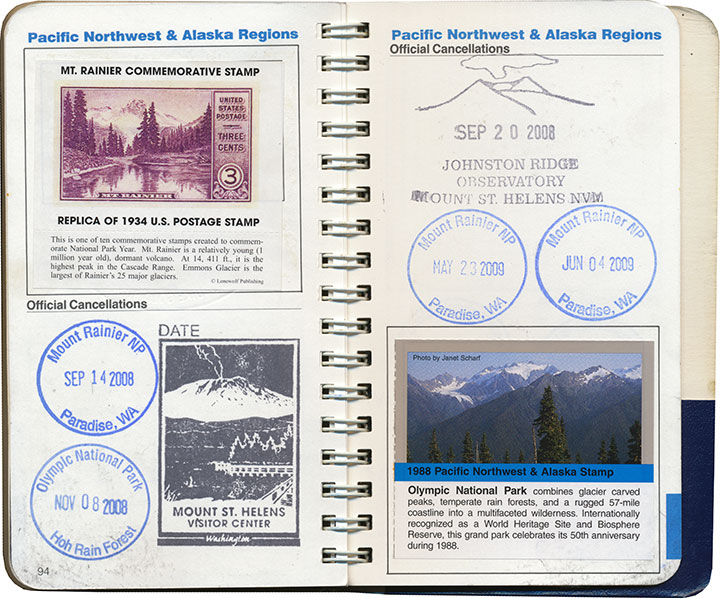

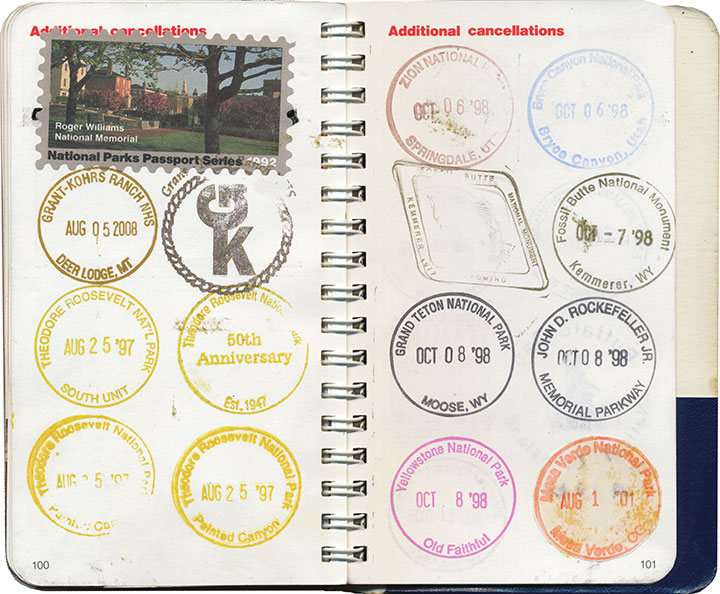

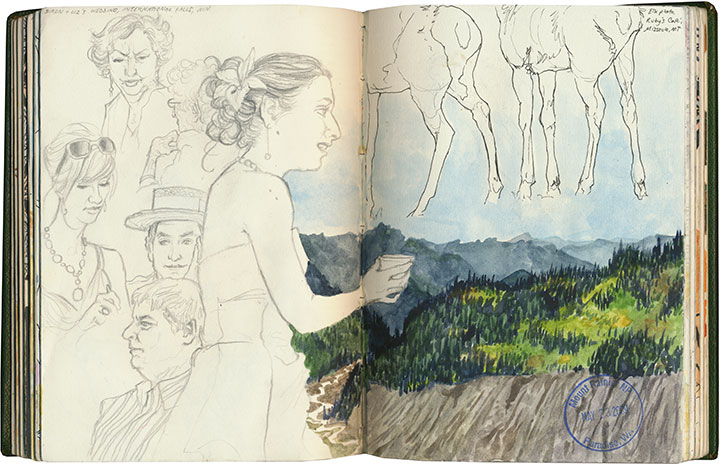

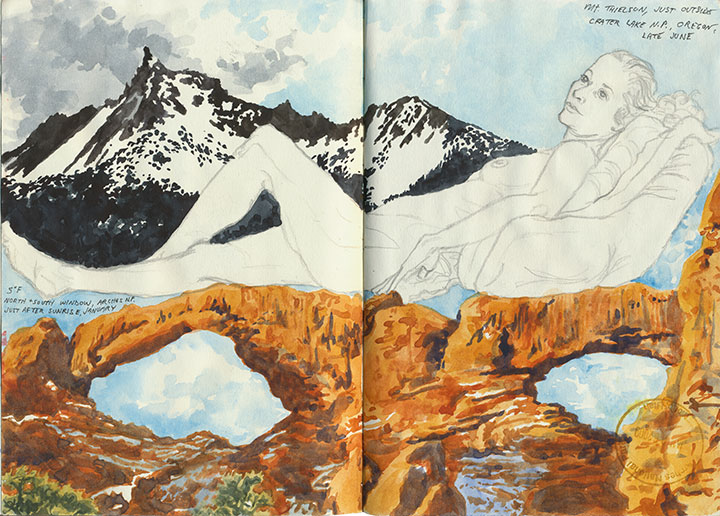

Since I posted this drawing and some others this summer, people have been asking me what’s with the stamps in my sketchbook. I guess the short answer is that each one is a little piece of personal tradition.

But you know I don’t really do short answers.

The long one, then.

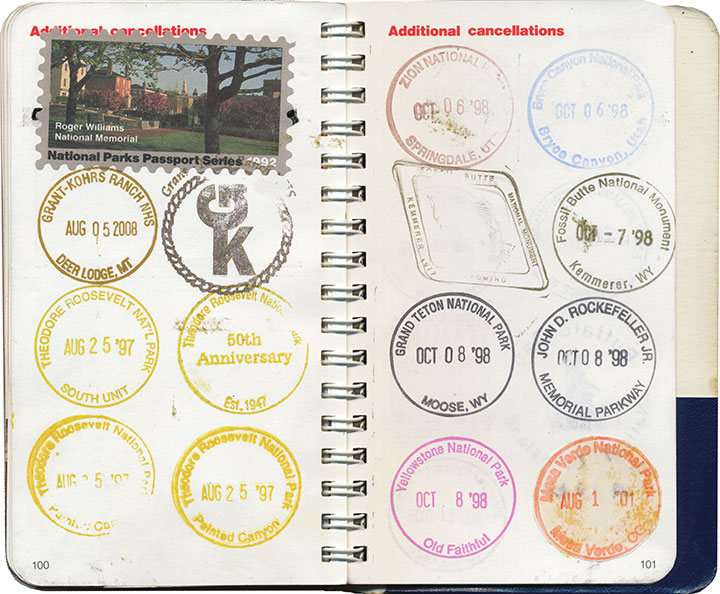

I grew up in a nomadic family. Between the moves required by Dad’s job in the Air Force and a fierce wanderlust that runs in all the O’Leary veins, we had a lot of reasons to travel. Dad and I, especially, would spend hours poring over our dog-eared Rand McNally road atlas, plotting routes over the back-est of back roads (the squigglier the line on the map, the better) and stops at as many points of interests as we could cram into a journey from A to B.

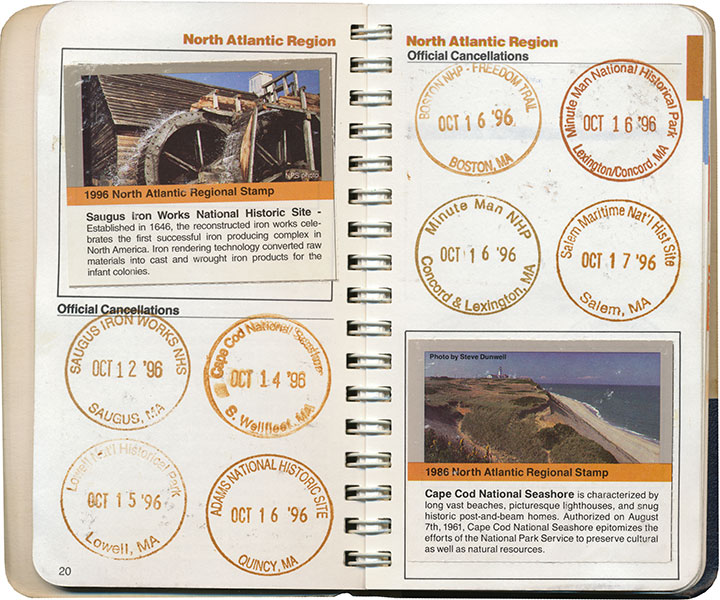

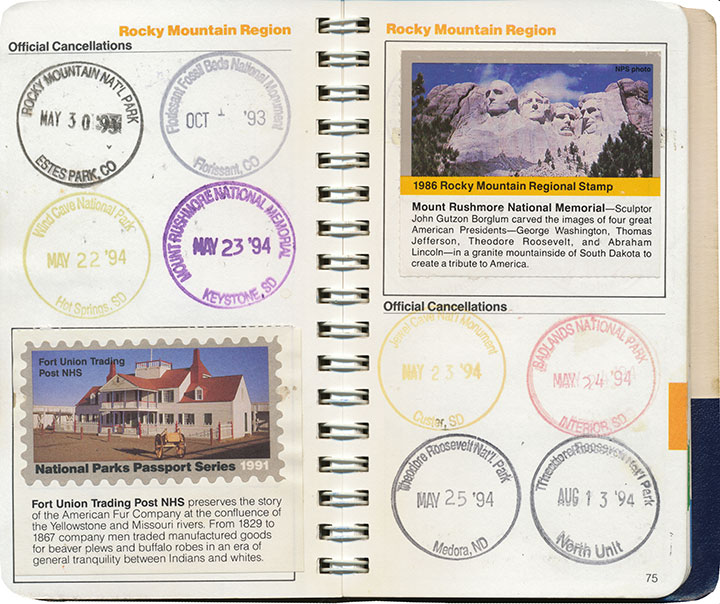

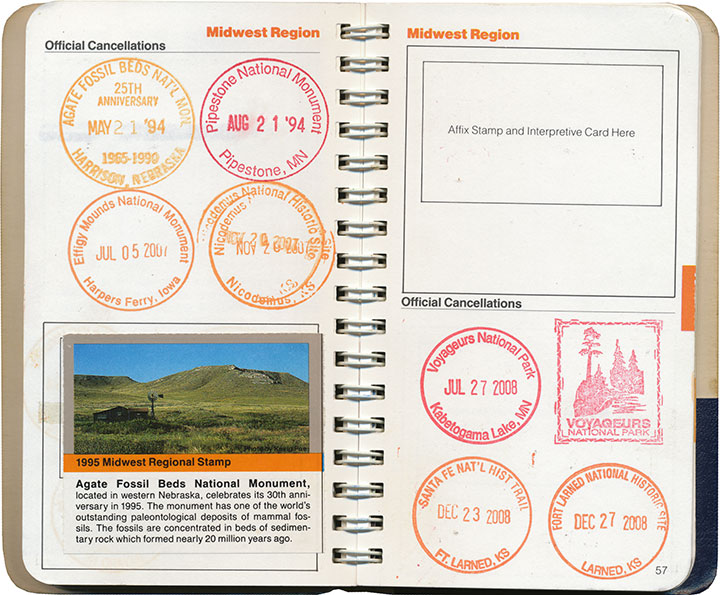

When I was ten, we made a circuit of our then-home state of Colorado, and devoted our time to exploring every national park and monument we could reach along the loop. At each park’s visitor center, we noticed a rubber stamp and ink pad stationed at the front desk. When we finally asked a ranger what they were for, she handed us a small blue notebook and proceeded to explain about the National Park Service’s Passport program.

A stamp to collect at every NPS property in the country, and a tidy little book to hold them all? I was hooked.

Dad and I found ways to sneak a national monument or two into every road trip and relocation—and even took impromptu vacations just to add a new park to the list. My favorite memory is when I was in high school, and Dad popped his head into my room:

“Have any plans this weekend?”

“Uh, no…”

“Wanna go to Montana?”

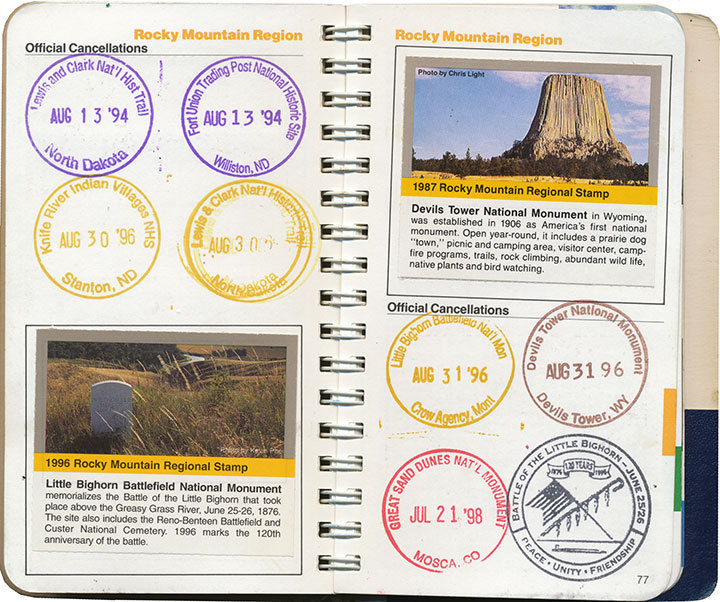

So we jumped in the car and drove 600 miles just to flip General Custer the bird at Little Bighorn (I had just read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, so he wasn’t exactly stirring me to patriotism). I mean, if you’re going to do it, you might as well go all out, after all. And we had the stamp to commemorate the moment.

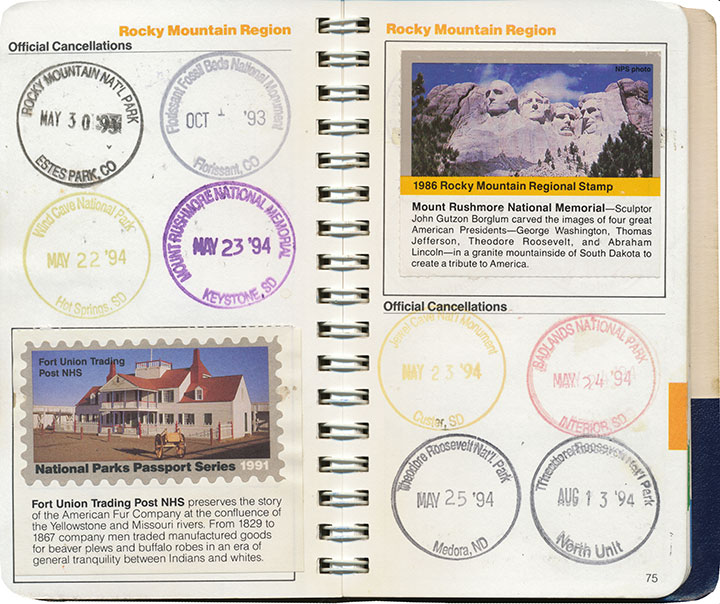

The Passport program also includes collectible paper stamps, which can be purchased from afar (as opposed to the ink cancellations, which are free but can only be obtained in person). I’m pretty lukewarm about these, though; by the time I jumped on the bandwagon they had already phased out the super-cool two-piece design pictured in the lower left corner above, in favor of the cheaper, lower-quality one-piece stamp in the upper right. Since those have been revamped yet again into a pressure-adhesive sticker—and who knows what heinously non-archival chemicals might be in the glue—I’m even less of a completist about them now.

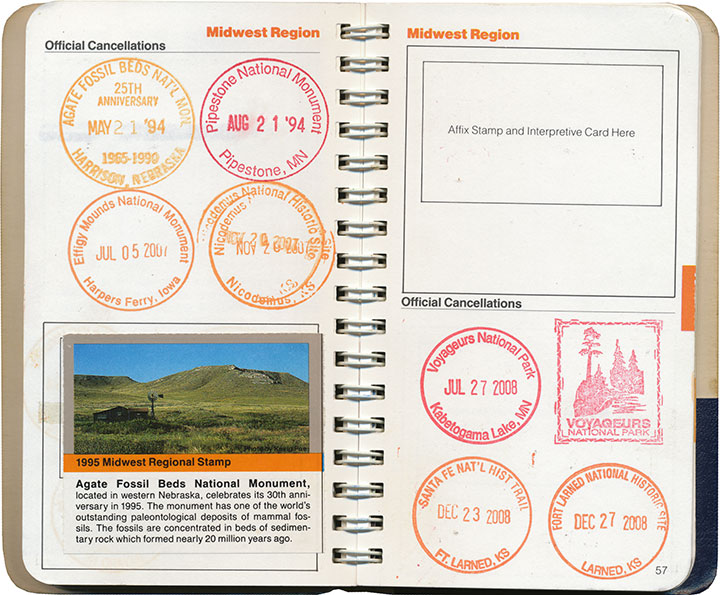

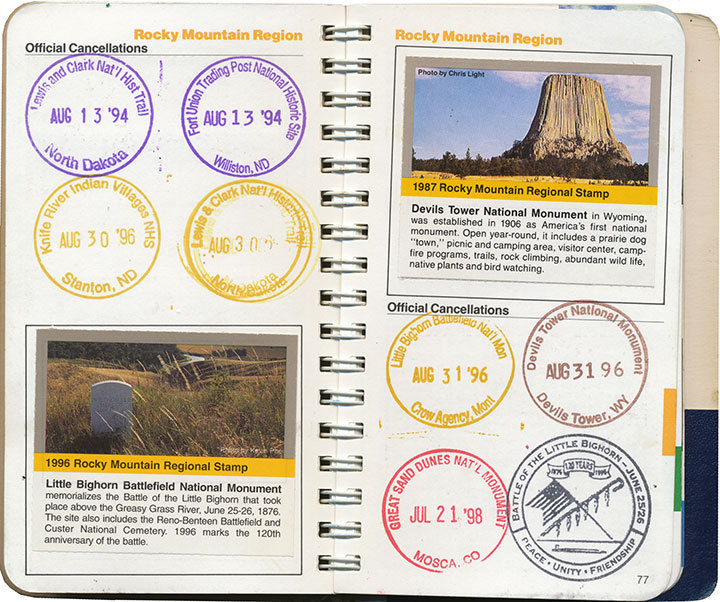

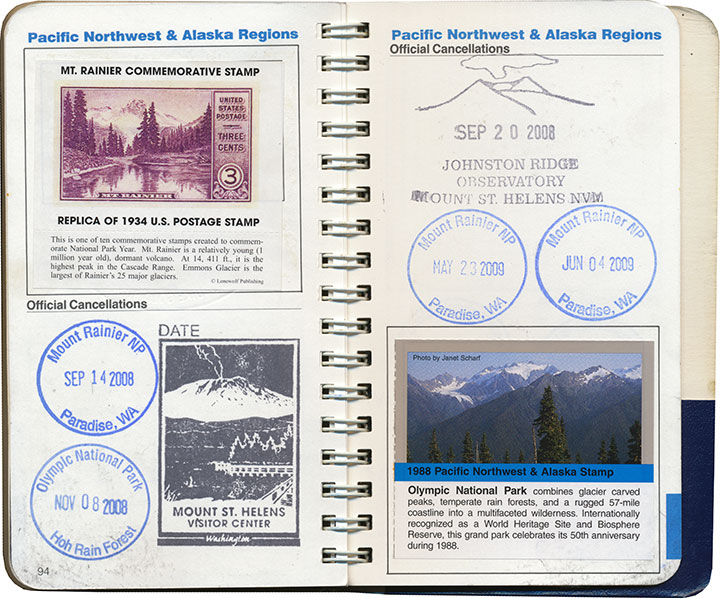

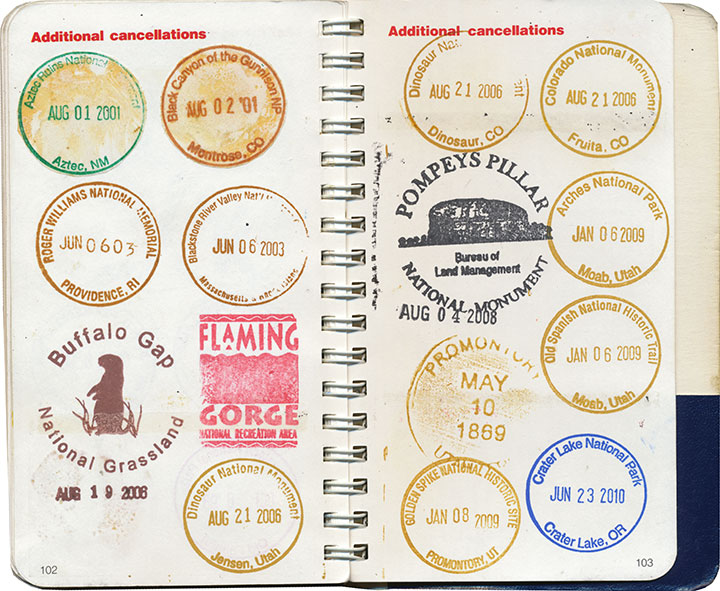

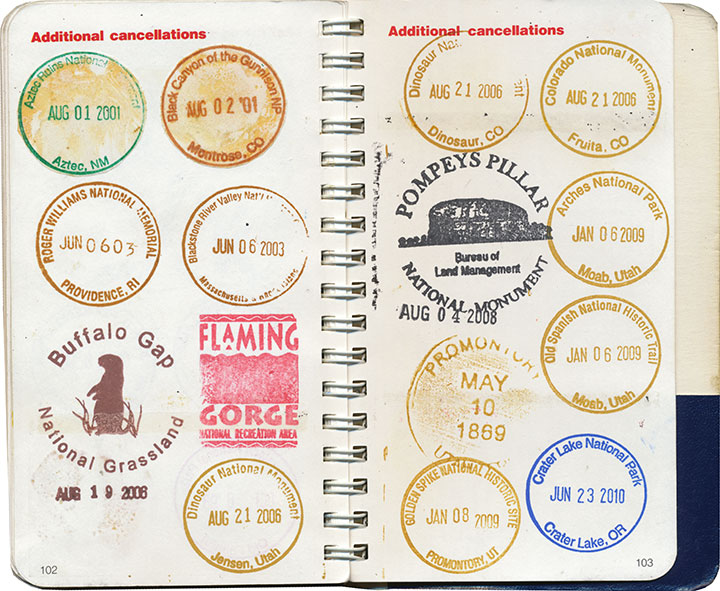

Anyway, I’ve burned through most of the regional sections in my Passport,

and every inch of overflow space.

So I’ve branched out a bit.

What I didn’t know as a kid was that my Passport helped me develop my interest in nearly everything I love most: traveling, design, archiving, printmaking, history, typography, bookmaking, and so on.

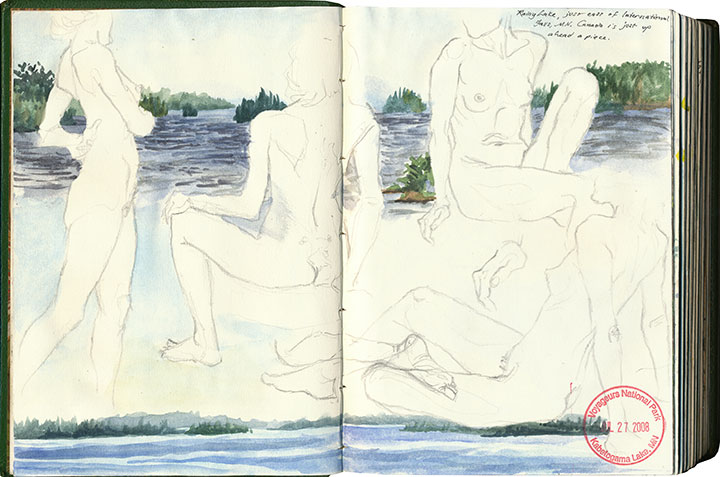

At some point along the way, I realized that what I really mattered to me (beyond the travel itself) was the act of adding to an ongoing work—and then looking back to see what I had accomplished. That what I had been doing all along, by compiling this little individual history, is creating some form of artist book. And that my frustrations over an imperfect format were really a desire to create my own.

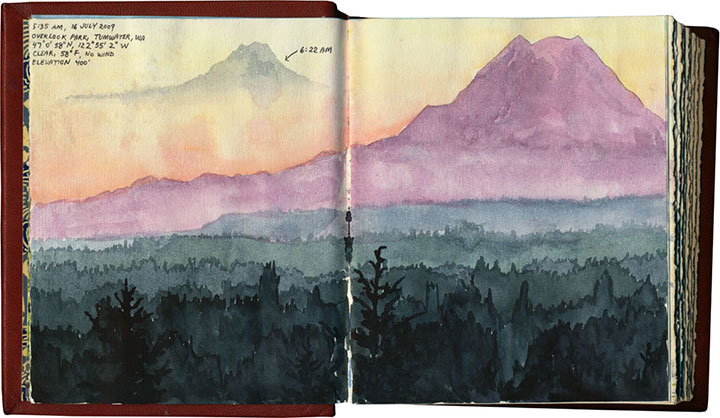

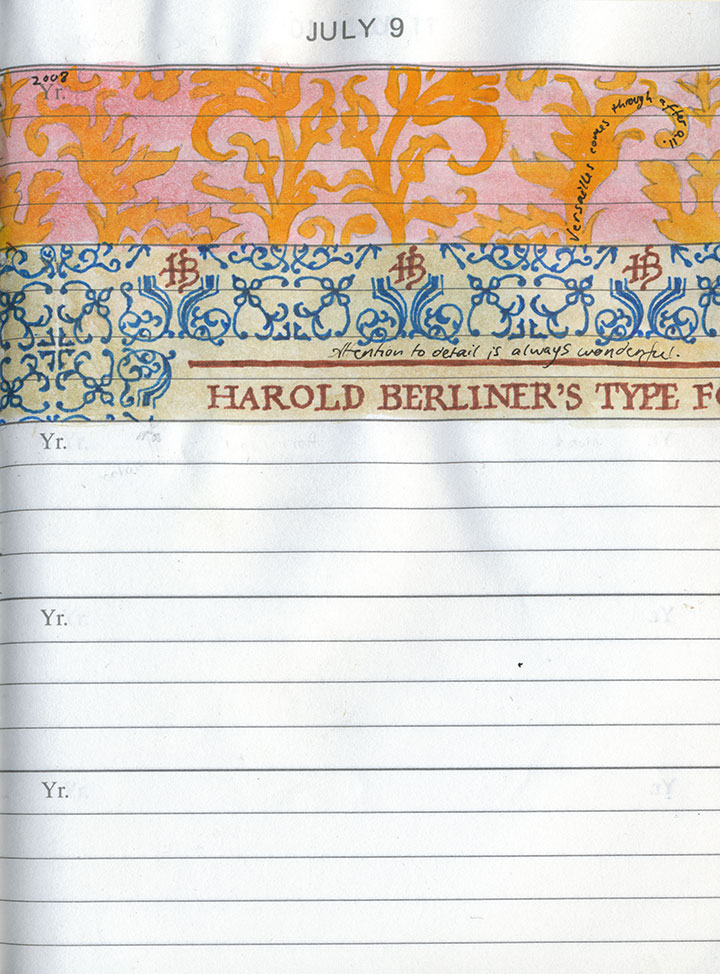

A page from my daily book—more on that here.

So now all of my sketchbooks are Passports, each custom-tailored—

each infinitely flexible, ready for whatever adventures wait to be documented.

Here it is, nearly twenty years later, and I’m as eager as ever. Moreover, it’s my goal to collect every last cancellation within the entire National Park System before I stamp the big passport book in the sky. I’m about a quarter of the way there.

And I’ll probably have to build a library for all the sketchbooks I’ll fill between now and then.

Save

July 17th, 2010

The second part of my little stolen holiday was a little more ambitious: a four-night camping trip with the Tailor in southern Oregon. It was just what the doctor ordered—the perfect prescription for recharging the soul.

We camped in the Rogue River National Forest, in a grove of hemlocks and blooming dogwoods, just downstream from this:

The Rogue is so beautiful that we could have spent the whole trip exploring its banks. Well, if we hadn’t had another destination in mind, that is:

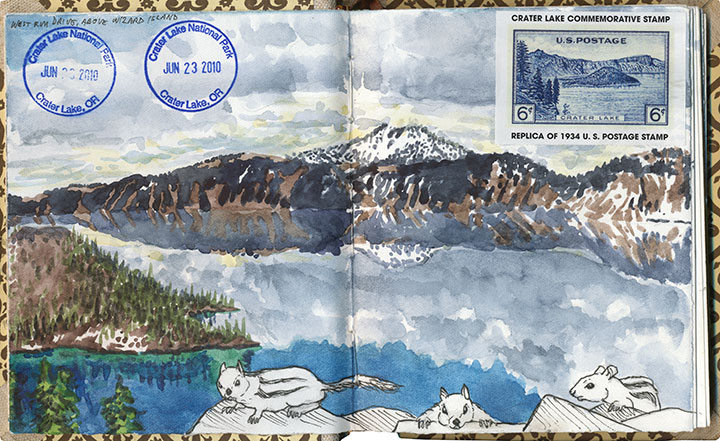

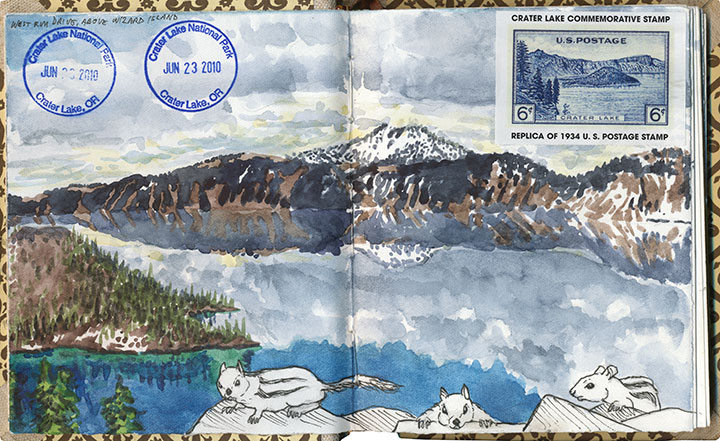

Crater Lake National Park. One of the deepest, clearest lakes in the world, Crater Lake was formed 7,700 years ago by the collapse of Mt. Mazama, after an explosion more than forty times the size of the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens.

When a group of prospectors stumbled upon it in 1853, and thus became the first white folks to lay eyes on it, they named it Deep Blue Lake. Heh. You can tell they worked hard to come up with that one. Well, at least it’s descriptive.

And accurate. The lake is so impossibly blue because of its depth; when the sun’s rays refract upon hitting the water, red and green light are absorbed in the depths, while only the blue light (which has a shorter wavelength) reflects back to the surface. So the lake is blue even on a cloudy day—as you can see.

We were a week too early for the boat tours to open for the season, but we hiked down to the water anyway. The rangers like to say that the trail is “one mile down, ten miles back up” (it’s funny because it’s true. Oy.), but the experience is well worth the huffing and puffing. Next time I’ll bring bug spray, though. Note to self.

Did I mention that it’s blue? And deep? Maybe those prospectors were onto something.

The photo above doesn’t come close to doing it justice (none of my photos do), but the sheer depth and clarity of Crater Lake was mind-boggling. It’s impossible to tell how deep the rocks in the upper left corner of the photo are, but according to the topo map in front of me, it’s quite a ways down. Because there are no streams in or out of Crater Lake, there’s nothing to muddy or disturb the water—objects are visible nearly 150 feet down. Deep Blue indeed.

The thing that really got to me was the fact that the lake was both a bottomless pit and a perfectly-flat mirror, depending on which way you looked at it. That’s probably why this is my favorite photo of the trip—somehow the camera managed to look at things both ways.

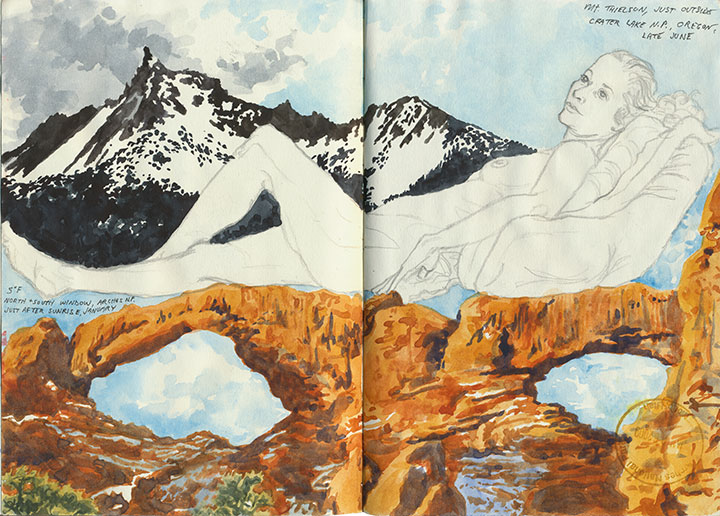

I think I must have been trying for the same kind of perspective with this drawing—and with far less success, I’m afraid. My brain broke when I tried to analyze the thing graphically. Ah, well. (The ground squirrels were fun, though.)

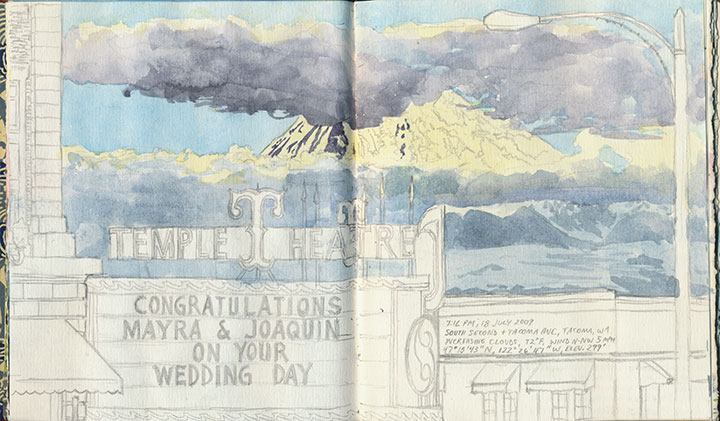

This one worked out a lot better—and it didn’t hurt that the figure and desert drawings were already there to help things along.

Speaking of deserts, we also saw a whole lot of barren landscapes to balance out all this snow and water. For one thing, we drove down and back on the eastern (the arid leeward) side of the Cascades. For another, there are places where all this ancient volcanic destruction still looks like it happened last year. This is the Pumice Desert, on the north side of the National Park.

And this is something else again. Now, I loved everything we’d seen at the Park, but my absolute favorite part of the trip was this place, which made for a side trip on the way home. This is just south of the Newberry Caldera, another collapsed volcano formed in precisely the same way as Crater Lake, but on a much smaller scale. A trail winds up and through the rock-pile hills—a landscape that seems plucked from the surface of the Moon.

If you step closer, however, you’ll see the light glinting off of each rock and pooling in every crevice. In full sunlight the entire hillside sparkles like a gigantic, blinding treasure hoard.

The rocks shine because they’re not rocks—they’re glass. This is obsidian, a natural glass formed when lava cools rapidly without crystallizing. Besides being gorgeous and just about the coolest thing ever, obsidian is extremely useful as a surgical tool. Obsidian scalpels can be sharpened to a near-microscopic edge (because of the not-forming-crystals thing), and the incisions they make produce narrower scars than steel scalpels do. Neat, huh? Anyway, obsidian flows of this size are quite rare, so if you get the chance to walk through one—take it.

I could have stayed all day with the obsidian (which, by the way, is called the Big Obsidian Flow, a name that gives Deep Blue Lake a run for its money), but we were still several hours from home (we figured we’d have to spend the first hour stepping carefully around all the ground squirrels that had appeared at our feet), and we still had one more stop to make:

Lava Butte, from which it was possible to see pretty much every darn volcano in Oregon, and even Mt. Adams in Washington. I won’t bore you with the 200 other photos I shot from up there, but let’s just say I was in suitable awe.

Oh, and for the record? All of these volcanoes are still active. How freaky is that? Or maybe it isn’t, and I just have volcanoes on the brain, but I think it’s freaky.

I lost count of all the volcanoes we spied, but the rest of the numbers were easy to tally:

Five glorious days.

Five breathtaking sunsets.

Five thousand smiles.

July 11th, 2010

Since I’ll be a hermit for most of the rest of the year while I finish my Rainier book, I tried to sneak a little stolen summer vacation time into June. If I was going to lock myself indoors during our sunniest season, I wanted as many mountains, oceans, flowers and skies as I could cram into a week first.

For the first few days we had a couple of friends staying with us. Since one of them was visiting from Colorado, and wanted a change from the hot, dusty summer back home, we took a day trip to the Olympic Peninsula for a good dose of lush greenery.

The West Coast highway, U.S. Route 101, ends with a 300-mile, two-lane meandering loop around the Peninsula. It’s the only thoroughfare on the entire Peninsula, and a treacherous road, full of hairpin curves, patches of fog, logging trucks and landslide-prone slopes—but the scenic beauty makes the drive a spectacular adventure.

We took the northernmost leg of the road that day. Just west of Port Angeles it winds through a tunnel of trees as it hugs the shore of Lake Crescent, where we stopped for a picnic lunch beside the impossibly blue water.

We were tempted to spend the whole day at the lake, but a bigger surprise lay down the road: the Hoh Rain Forest, one of the largest of America’s rare temperate rain forests. I’d also bet it’s the most beautiful—if it weren’t a four-hour drive away, I’d go every day.

I had only ever seen the place in a downpour (big surprise—they get up to fourteen feet of rain and over 300 cloudy days a year), but as soon as we arrived that day … the sun came out.

I almost didn’t recognize the place.

The last time I was there, droplets hung from every surface and everything shimmered with a gossamer silver glow.

This time, the glow turned to spun gold and bottle green.

As always, though, every branch was festooned with cat-tail moss, and sword ferns carpeted the forest floor.

And the clover leaves were the biggest I’ve ever seen.

So were the trees.

The best part about our road trip was the fact that it was nearly Midsummer; we still had hours of sunshine left to us. Next on the itinerary: Ruby Beach. It was a short hike down to the water, past Queen Anne’s lace and just-ripening salmonberries, with the roar of the Pacific ringing in our ears.

That bizarre stamp is still the only banana slug I’ve ever seen, alas. The search continues!

I sat down to do a watercolor,

while Ethan moved along the shore to explore the sea stacks,

and Nicole stopped to take in the view.

We made a quick contribution to the collection of obos on a nearby driftwood log, and set off for home.

Yes. Twilight firewood. For setting those vampire books on fire, I think.

On the way back we stopped for a little absurdity. Route 101 passes through Forks, home of a certain infamous vampire series; we couldn’t resist stopping to take photos of the hilarious roadside tie-ins that had popped up since the last time I passed through. I’d never read the books, but when Nicole told me that these vampires only eschew sunlight because it makes them sparkle … well. My morbid curiosity got the better of me, and before I could stop myself, I read the whole blasted page-turning accident scene of a series the following week. Ugh.

And, uh, yeah. They sparkle. And whine and brood and mope. Curiosity satisfied.

I digress. Sorry.

By that point we were starving—but not in the mood for Twi-dogs or whatever punny food might be expected in a place with a name like Forks. So I suggested we hang on a little longer and head to Port Townsend, where I knew of a fantastic seafood restaurant.

An hour later, we had traded Forks for spoons, and were digging into our bowls of the tastiest, freshest, localest carn-starn Manila clam chowder on the West Coast. And changing my definition of road food in the process.

Oh, who am I kidding? You know that whole trip was for the chowder, right?

May 18th, 2010

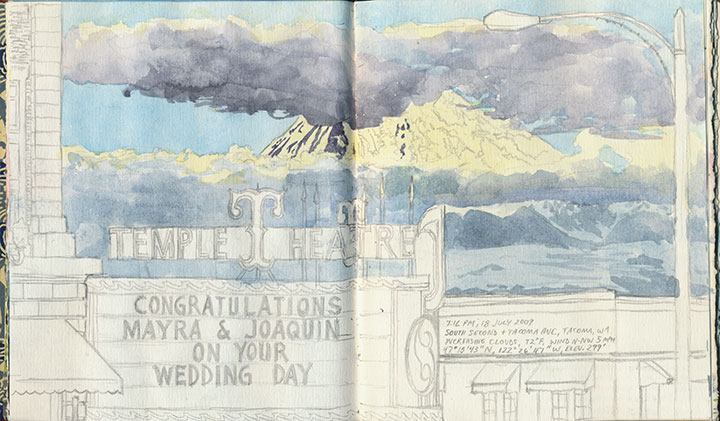

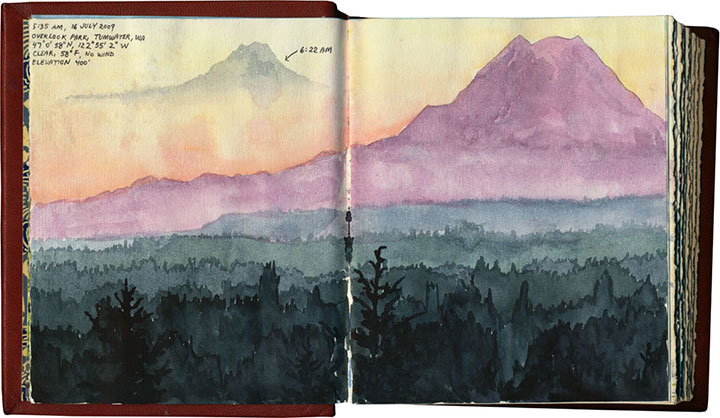

I’ve had volcanoes on the brain for nearly two years. Littering my studio are volumes of sketches, nearly 6,000 photographs, reference books, stacks of maps, and a brand new, functional prototype of the artist book about Mt. Rainier I’m working on—all evidence of my attempts at capturing a series of fleeting moments and freezing them in time and on paper. (Rainier is hiding there in the clouds, at the bottom of the above photo—but what I love most is that the cone looks like an erupting volcano! And speaking of which…)

Photo by the U.S. Geological Survey

And then there’s the little corked bottle of volcanic ash on my desk, inscribed with the date of the last major eruption of Mount St. Helens: exactly thirty years ago today.

I’ve been staring at that bottle on and off, all day, reminded of why I’m doing all of this (and why I can’t wait until I have something to show you!).

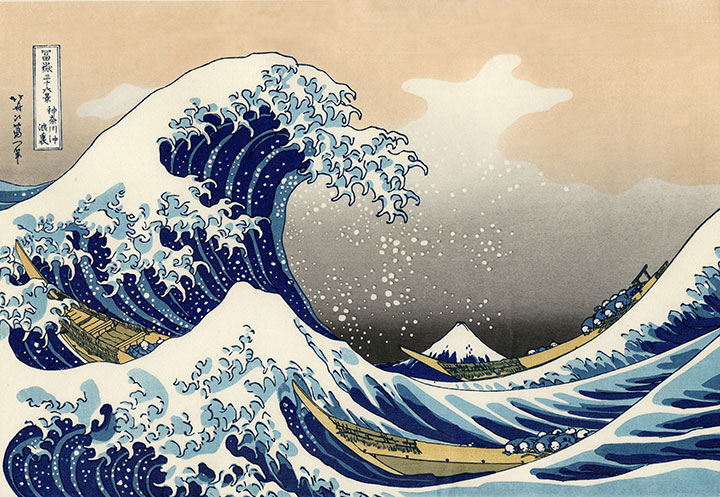

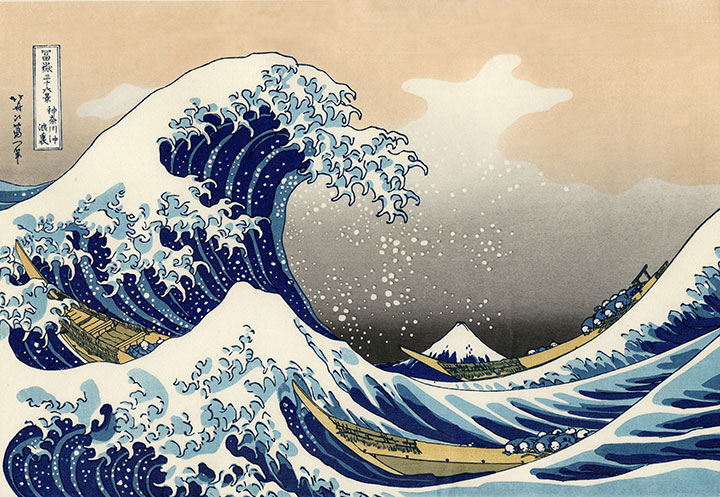

This project began as a tribute to Katsushika Hokusai, the Japanese printmaker and illustrator who created his famous Views of Mount Fuji woodblock series over 150 years ago.

Hokusai wanted to demonstrate the unchanging immortality of Fuji amidst the transient nature of everyday life. To him, Fuji was forever, an unshakable icon of Japan and one of the foundations of his culture.

The trouble is, Fuji is a volcano—just like Rainier and St. Helens—that by its very nature is constantly changing right along with the lives being lived in its shadow. That knowledge is where I found the root of my own project, and since then I’ve tried to document the fire mountain in my own back yard—to be there for every change and permutation.

Today’s date lit a bit of a fire under me, and prompted me to get on with the business of finishing this artist book. Because one day this is all going to happen again. Mount Saint Helens will be first, I’d wager; being the most active and youngest volcano in the Cascades, it may only be a matter of a few years. And some day, even if it’s a hundred or a thousand years from now, Rainier is going to have its turn, too.

For now, though, I’m just doing my best to pay attention to the present moment, because one day I may need help remembering how things used to be.

March 6th, 2010

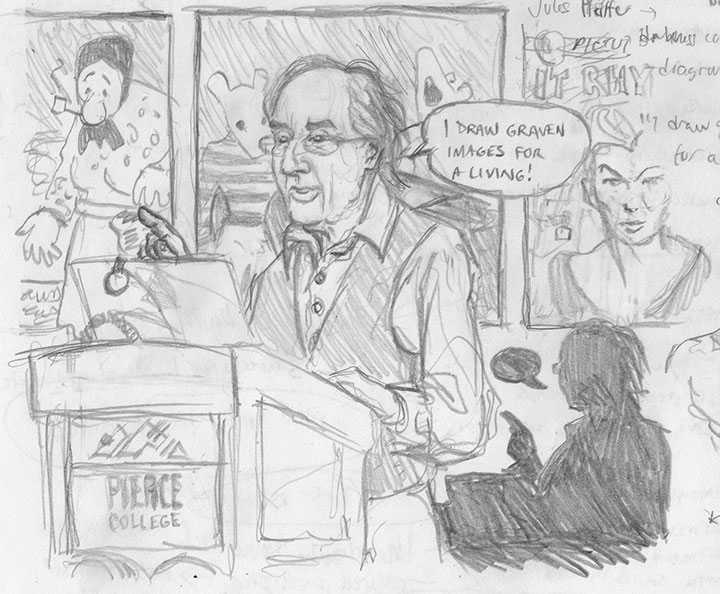

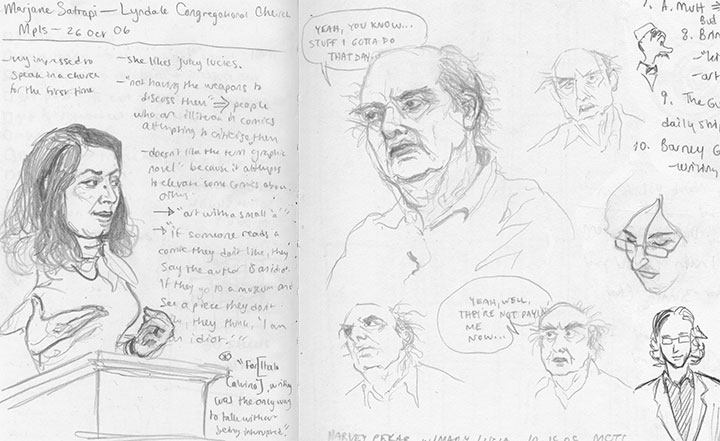

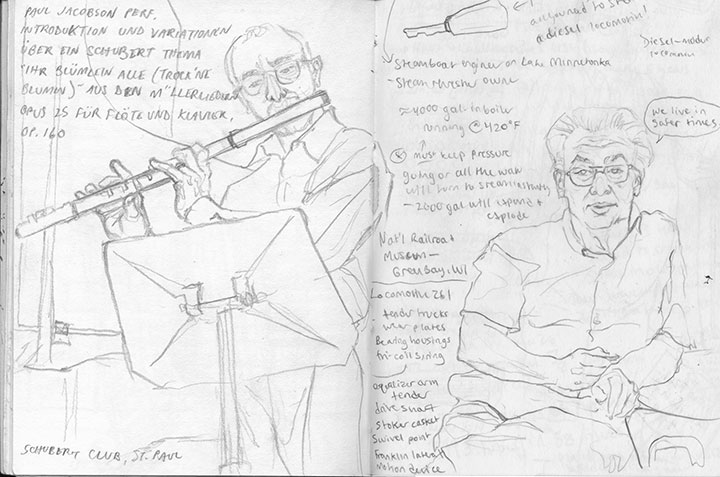

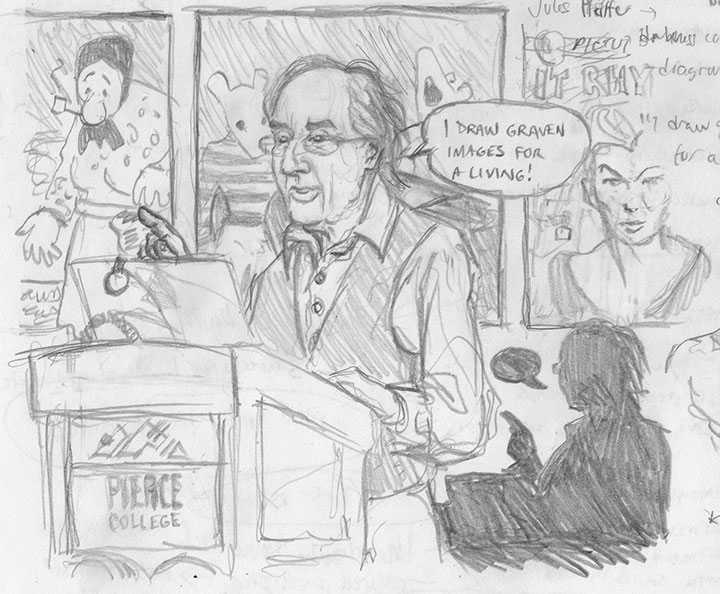

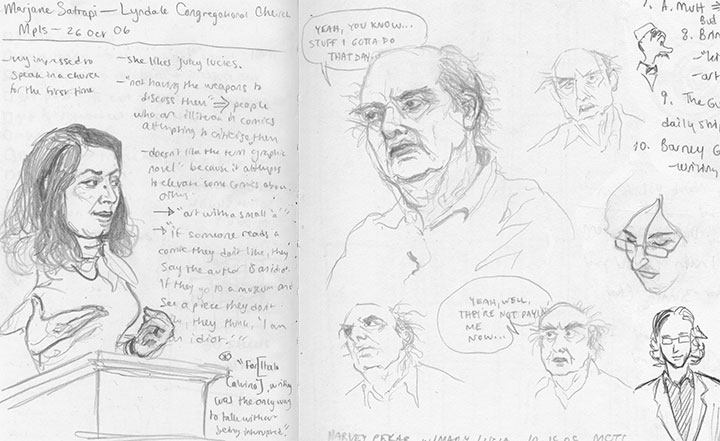

The other night I went to a talk by comics artist Art Spiegelman, and as usual, brought one of my trusty sketchbooks with me. Since comics and I go way back, and I’m a big Spiegelman fan, I think I got a little carried away with the doodles accompanying my lecture notes. I was a little abashed when the people next to me noticed and commented; all I could say was, “I do this a lot—it helps me remember.”

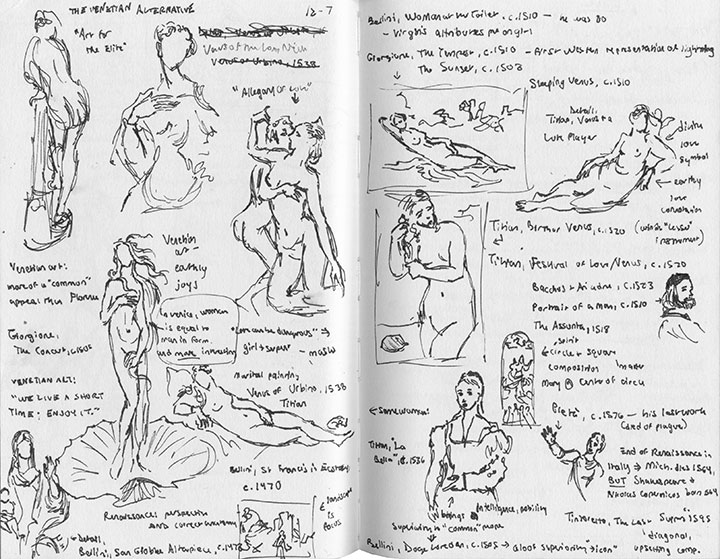

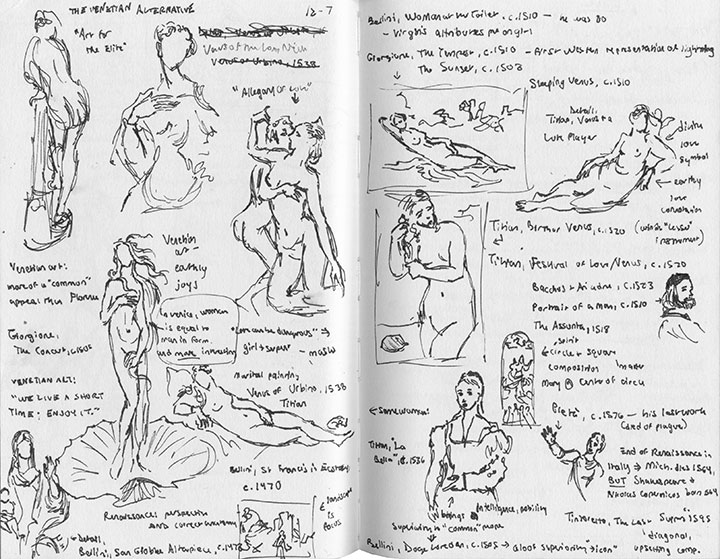

I’ve always been an obsessive note-taker, but I discovered in college that adding sketches to my notes went a long way towards my good grades in art history (this must have been the “Naked Ladies of the 15th and 16th Centuries” lecture or something).

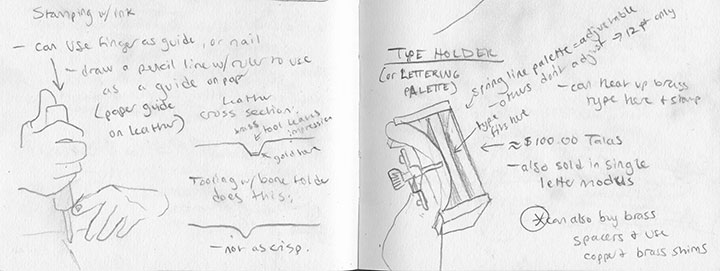

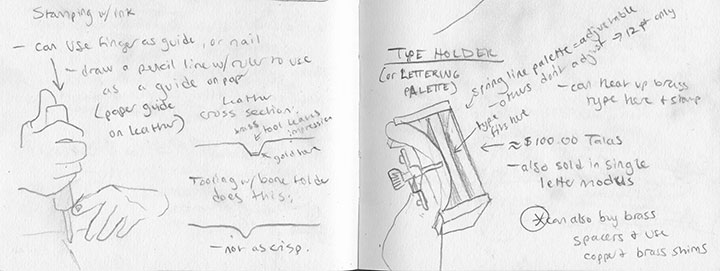

Then when I fell in with the book arts, drawn diagrams were a godsend for remembering complicated equipment and technical processes.

By the time I graduated, the habit was ingrained. I found not only that drawing was an excellent memory trigger, but also helped me focus on the moment at hand.

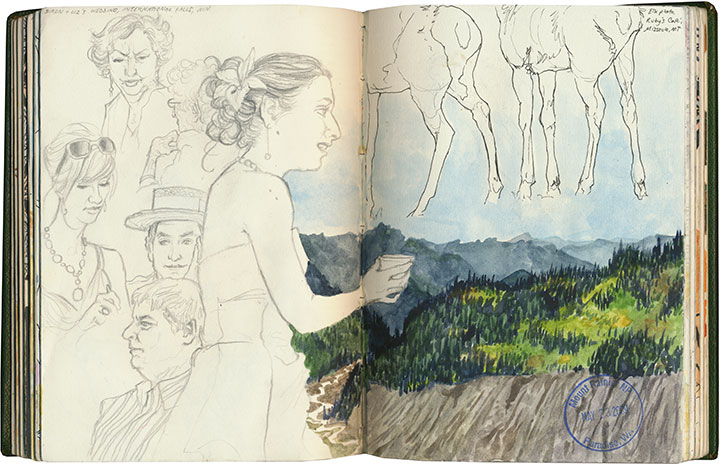

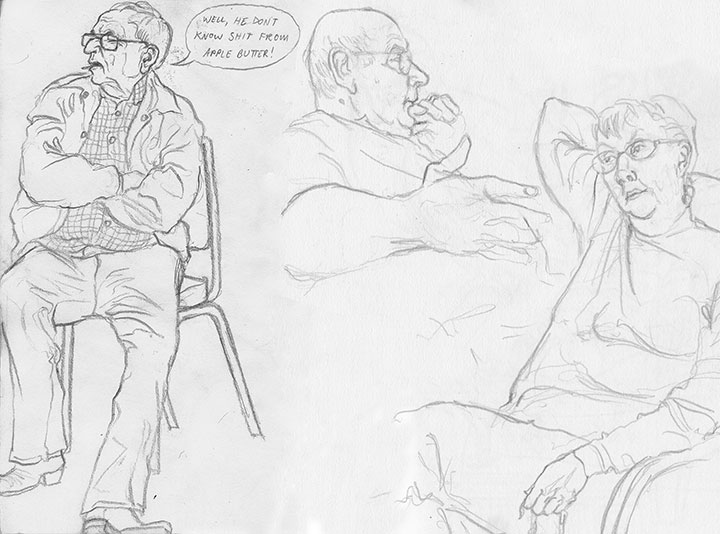

The comments on my Spiegelman doodle reminded me that I had a funny habit of drawing comic artists and writers (from the left, Marjane Satrapi, Harvey Pekar, David Mazzucchelli)—and often portraying them as comic-book characters themselves. As I dug through something on the order of fifteen sketchbooks to find my grumpy Pekar sketches, I unearthed scores of these things, from all manner of locations and events:

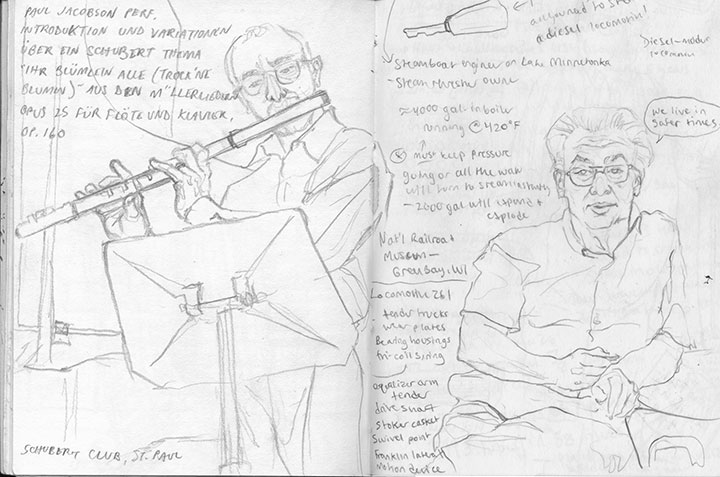

classes, performances and lectures;

public transit and airports—

—among other things—

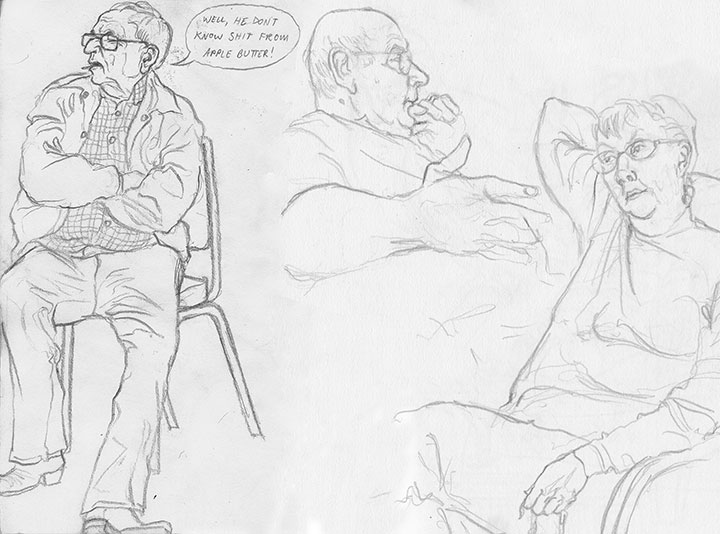

family gatherings (yes, I quoted the above verbatim; that’s the Tailor’s uncle, and he’s comedic gold);

work meetings;

restaurants, coffee shops;

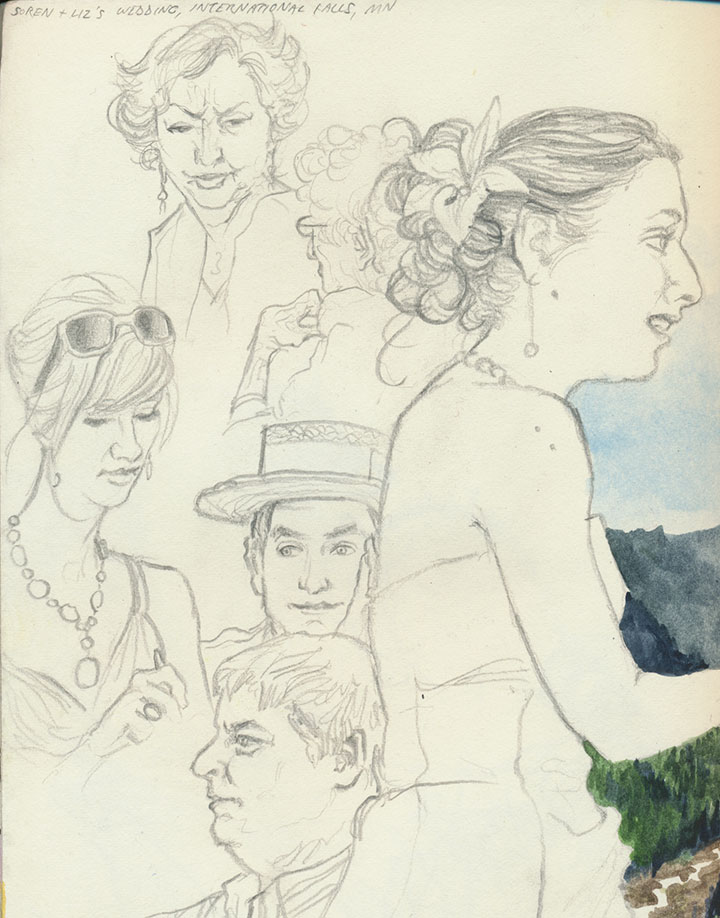

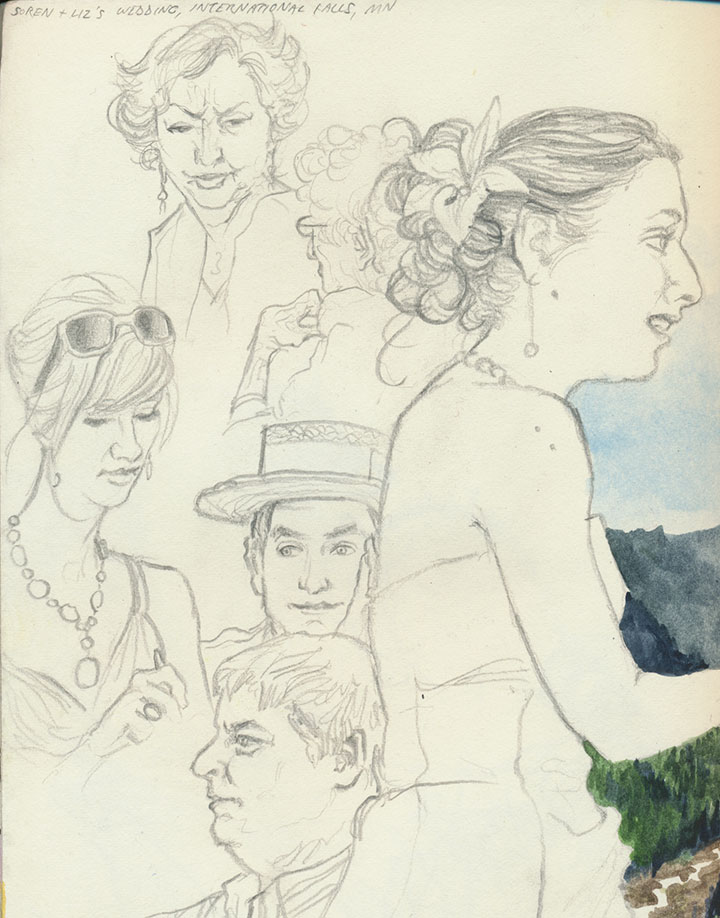

wedding receptions;

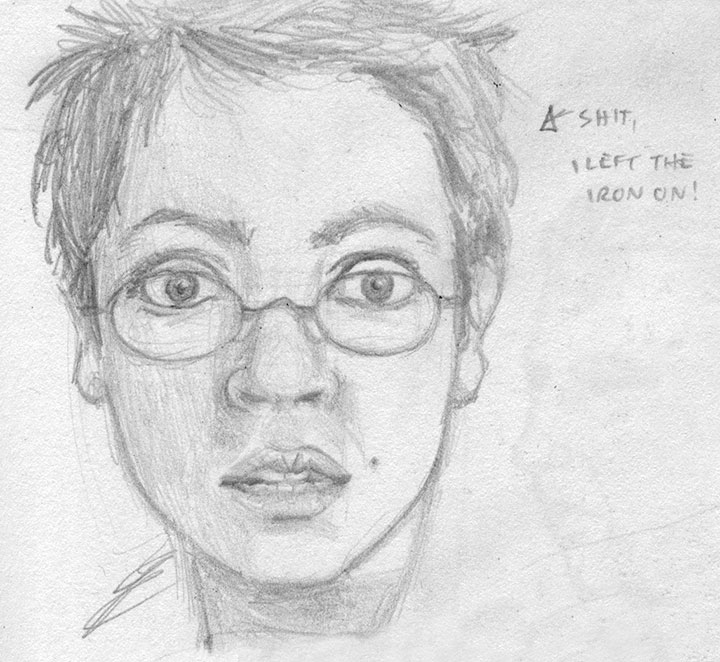

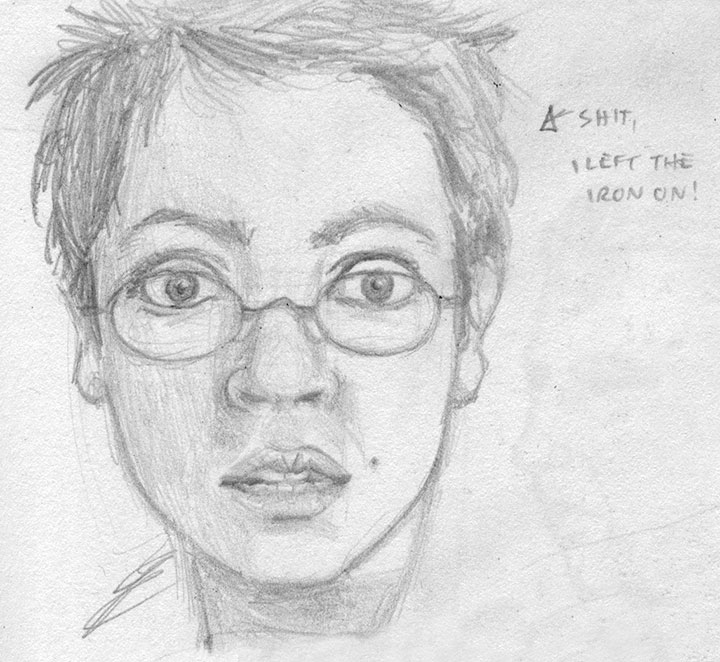

and even my own mirror, when I’m working alone (that one’s an oldie from college).

I draw when I’m trying to document an event, when I’m nervous, when I encounter a particularly unusual face, when I’m telling a story of an odd person I saw that day, when I want to preserve a loved one, and even when I’m not really aware of it—I found plenty of sketches that I had no memory of making.

Maybe there’s some psychological disorder that lists obsessive and semi-conscious sketching as a symptom, but this is one compulsion I’d like to hold on to. I know I spend more time drawing the speaker than taking actual notes, but if I remember the content just as well, I suppose it all comes out in the wash. Besides, I can’t possibly be the only one who does this, right?

Right?

February 10th, 2010

The past couple of weeks have been an absolute whirlwind, and when I look in the mirror I see a walking, talking to-do list. The notes-to-self strewn all over the studio (among half-finished boxes, reference materials, pencil layouts, proof prints, watercolor pans, etc.) aren’t enough, so now I’ve taken to muttering little reminders under my breath—call this client, mail this order, drop off this pile of prints, invoice this subscriber, edit this illustration, proof these plates, cut this book cloth, list these cards, upload these photos, etc.

I needed a break. So today I bolted to Seattle to clear my head.

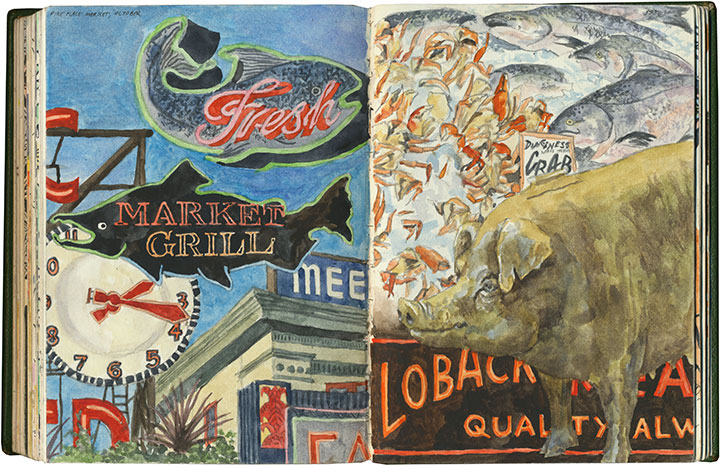

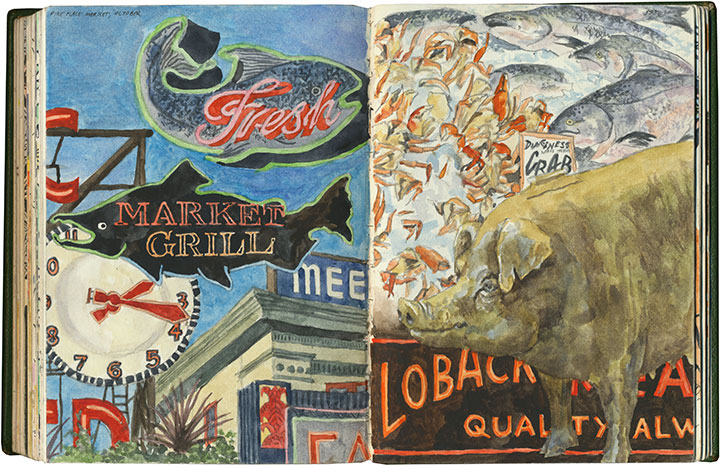

One of my favorite hobbies is wandering around the Market alone, especially on winter weekdays when it’s pretty much empty. Losing myself among the fruit stalls and neon is as therapeutic as meditation.

I wasn’t in the drawing mood this time, but the Market is also on my short list of all-time favorite sketching haunts. This is one from a year ago or so, on a completely packed, sunny Saturday, when I flattened myself against poles and ducked down onto the curb to draw without being trampled by tourists.

I love it for the people-watching when it’s crowded, but there’s something special about having the place to myself. There is a downside, however (besides being heckled by bored fishmongers): it’s awfully hard not to splurge on sampling from the unbelievable smorgasbord of fresh goodies.

Now how could I say no to that?

January 10th, 2010

I find I’m spending more time at the drafting table these days, and far fewer hours chained to the computer. This month I am blessed with an assistant—a brilliant young woman who is helping me with my administrative and production work, in exchange for school credit, a little professional experience and the chance to beef up her design software skills.

We’re lucky to have here in T-town an arts-magnet public high school, and part of the curriculum for juniors and seniors is an internship opportunity during the winter term. I was completely ignorant of this until I received Zooey’s email last fall, asking if I would be willing to take her on. I almost turned her down, simply because I couldn’t imagine I’d have enough to keep her busy and interested for three 40-hour weeks.

But then it occurred to me that I might be able give her an accurate idea of what it’s actually like to make one’s living as a full-time artist—which largely consists of being one’s own secretary, account manager, bean-counter, marketing department, production assistant and gopher, as well as coming up with all the creative ideas. That’s something I wish I had known as a student, and yet was certainly never taught in art school.

As it turns out, there’s plenty of work for both of us, and it’s been a mutual learning experience. Zooey (not her real name, in keeping with my little privacy policy) is picking up design skills they aren’t teaching at the high school level, attending client meetings and press checks, learning the ins and outs of seeing a project from concept to completion, and contributing her own ideas to creative discussions and brainstorming sessions. And I’m able to spend more time actually creating artwork, rather than endlessly playing catch-up with back-burner projects that should have been done months ago (although I crossed my heart and made her a solemn vow that I would get my own damn coffee).

The best part is having good company during the day. Running a one-woman shop is pretty solitary work, and learning that Zooey is not only a talented artist but also a mutual audiophile and movie geek made her an instant kindred spirit. (It was funny to discover that we both have a habit of singing along with the background music, but often choose different vocal parts to follow: harmony is so much more fun than a solo.) So these days I’m churning out new work and ideas faster than ever, while Zooey keeps a hand on the metaphorical wheel—and all the while the studio is filled with music and laughter.

I’m a control freak by nature, so I’m pleasantly surprised to find myself capable of letting go of the reins a bit. And I was even more surprised to learn that Zooey is the only student working with an individual artist this year (everyone else is working with firms or large companies). Here’s hoping that other artists and freelancers open their doors and minds to future students—there’s so much to learn, on both sides.

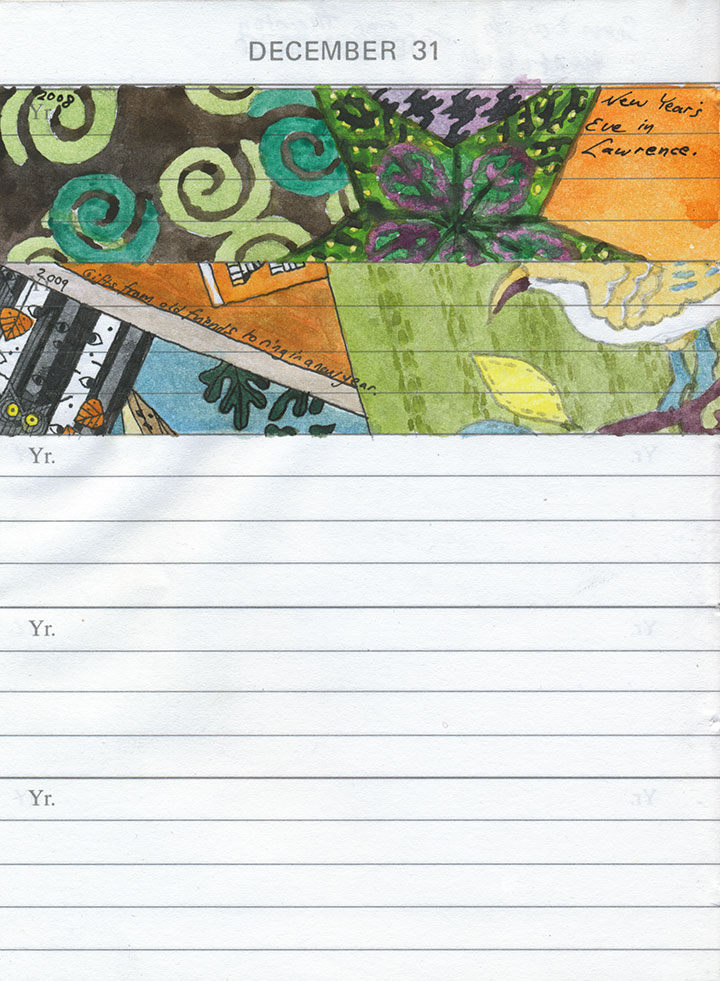

December 31st, 2009

End-of-the-year summaries have never been my strong suit, not least because I tend to measure time on completely different terms than the standard calendar (like counting up from the anniversary of an important event, for instance). And since nobody seems to be able to agree on whether the decade ends this year or next (anyway, doesn’t any ten-year span count as a decade?), I think I’ll leave that one alone as well.

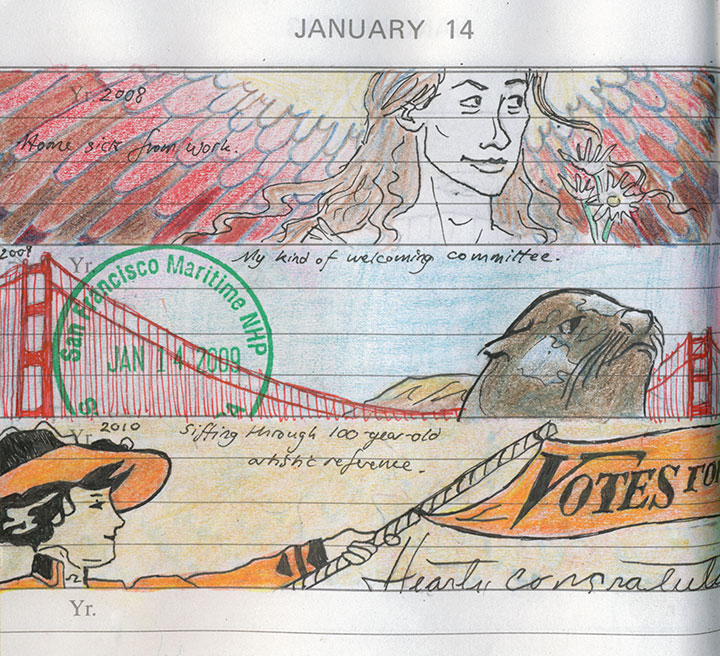

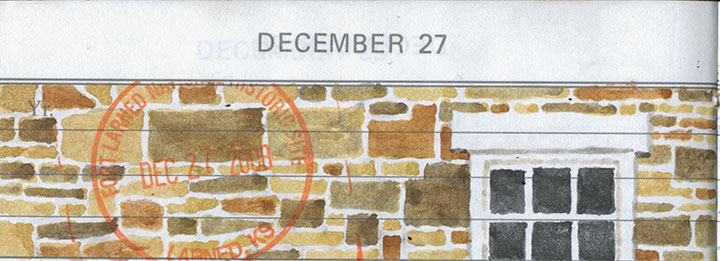

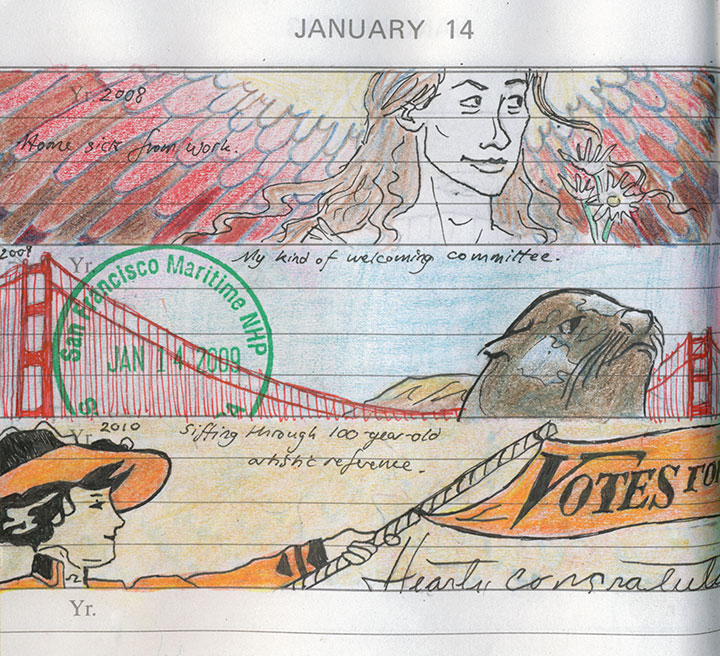

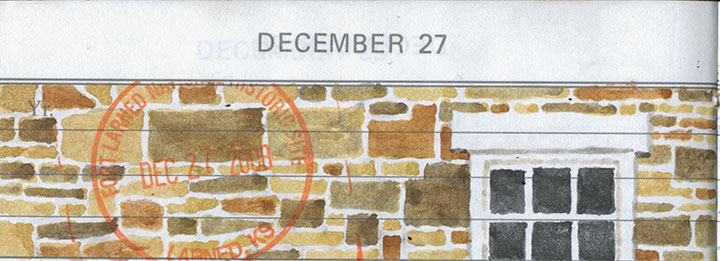

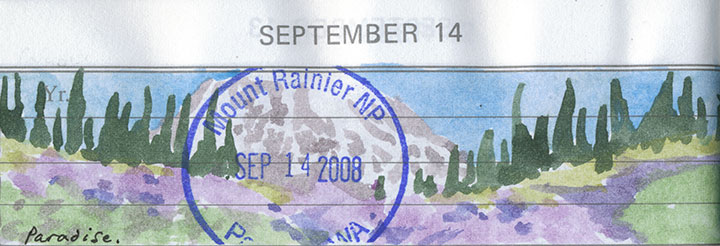

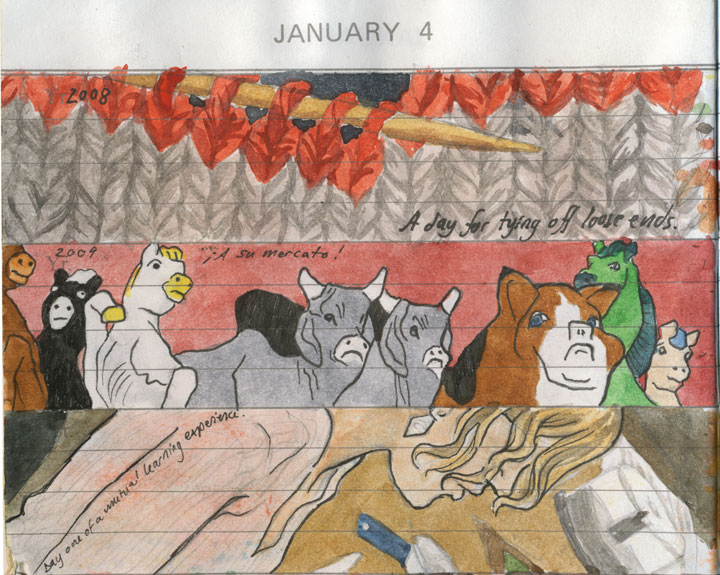

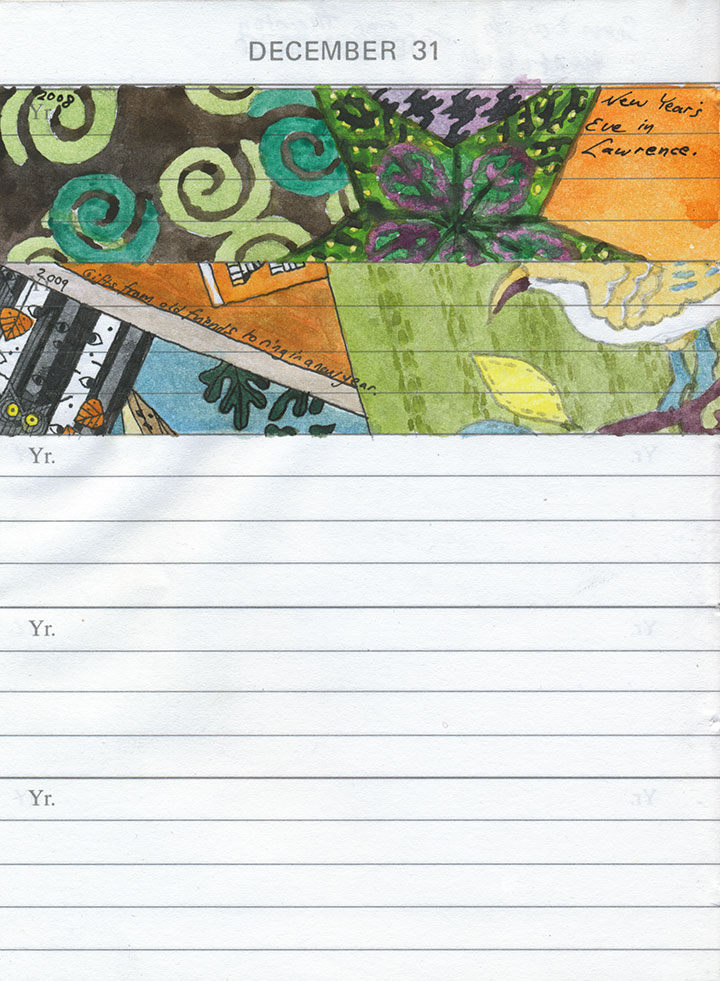

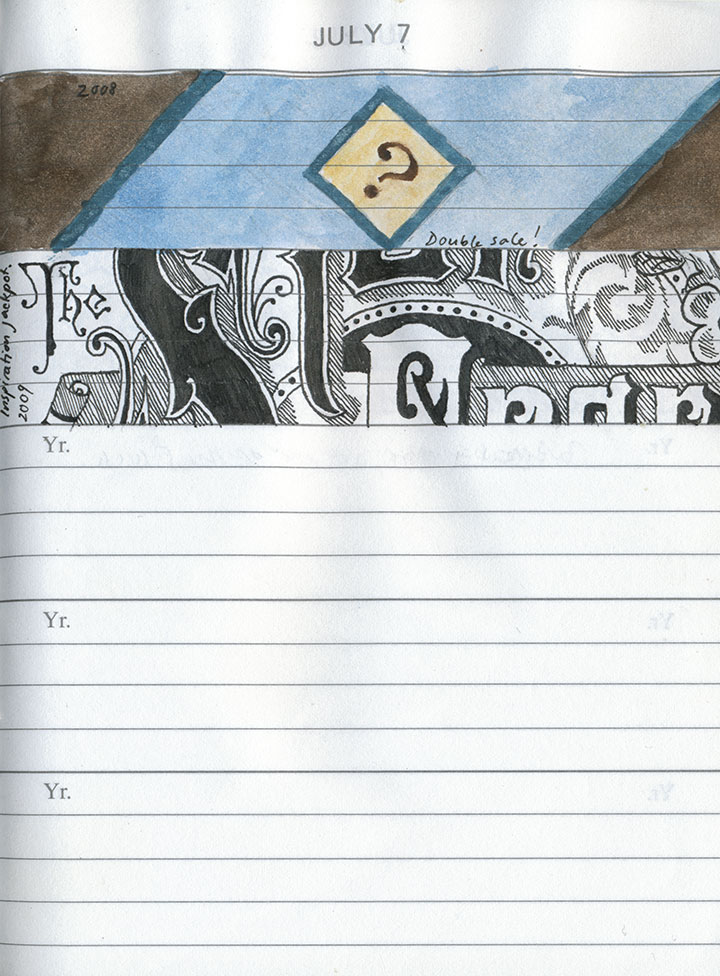

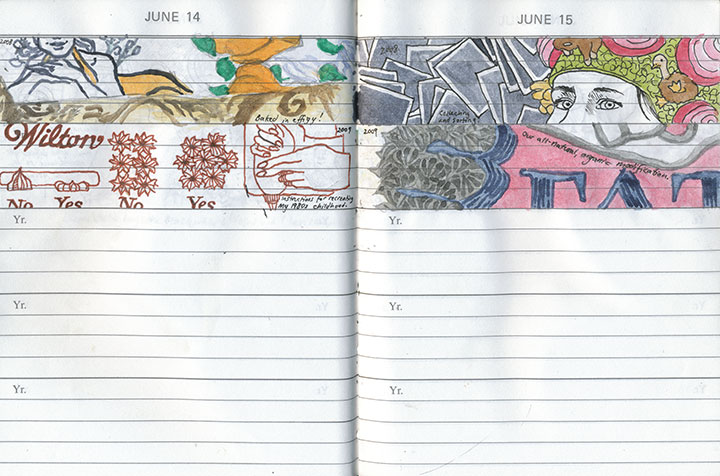

Instead, I thought I’d share my own way of marking time—an experiment that I’ve been working on for two years now.

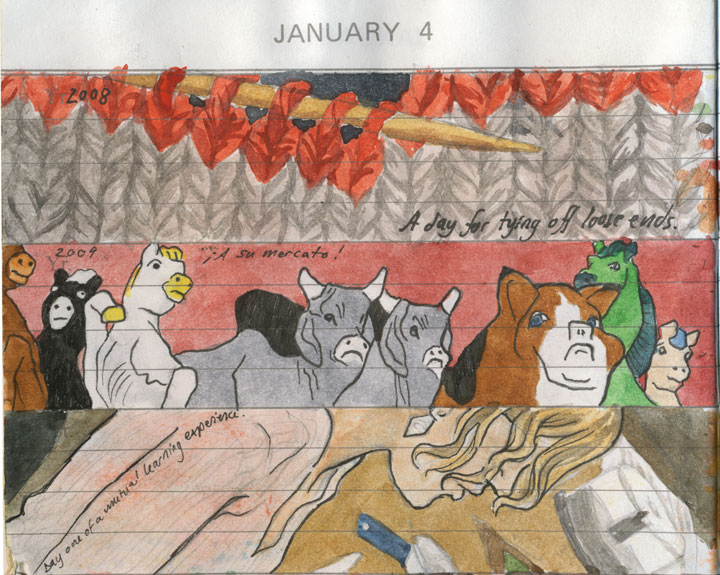

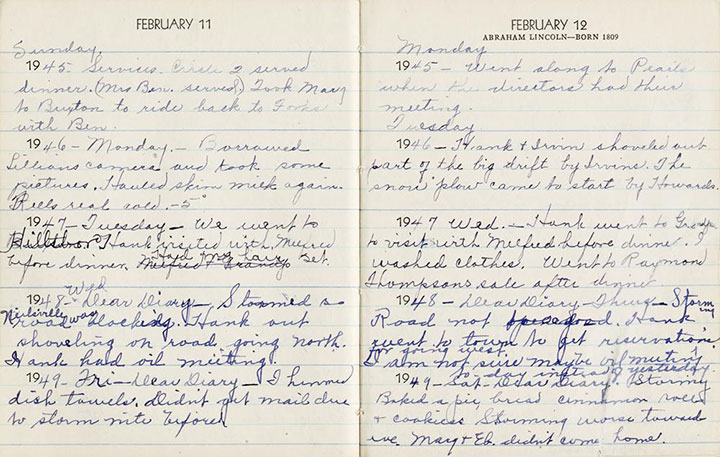

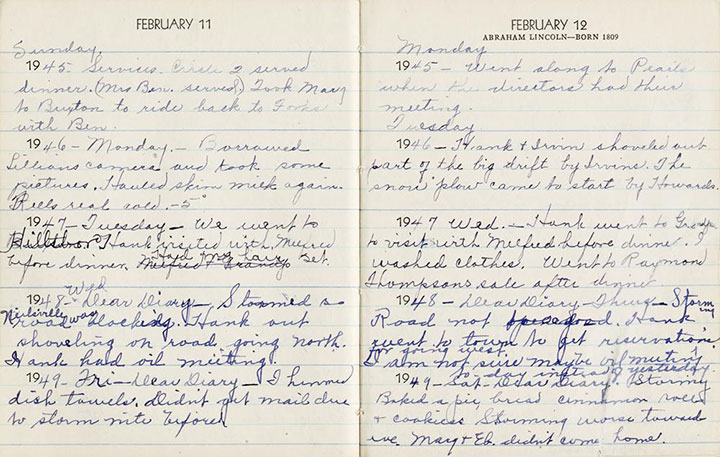

My friend Sarah Christianson has spent the last several years documenting the history of her fifth-generation family farm. Among her family artifacts are several of her great grandmother’s daily diaries, which Mrs. Anderson faithfully kept for many years. As you can see, there isn’t much space to write (so most entries say things like, “Went to the store, visited with Mildred,” etc.)—but what really interested me was how the five-year format of each page paints a larger picture of a woman’s life.

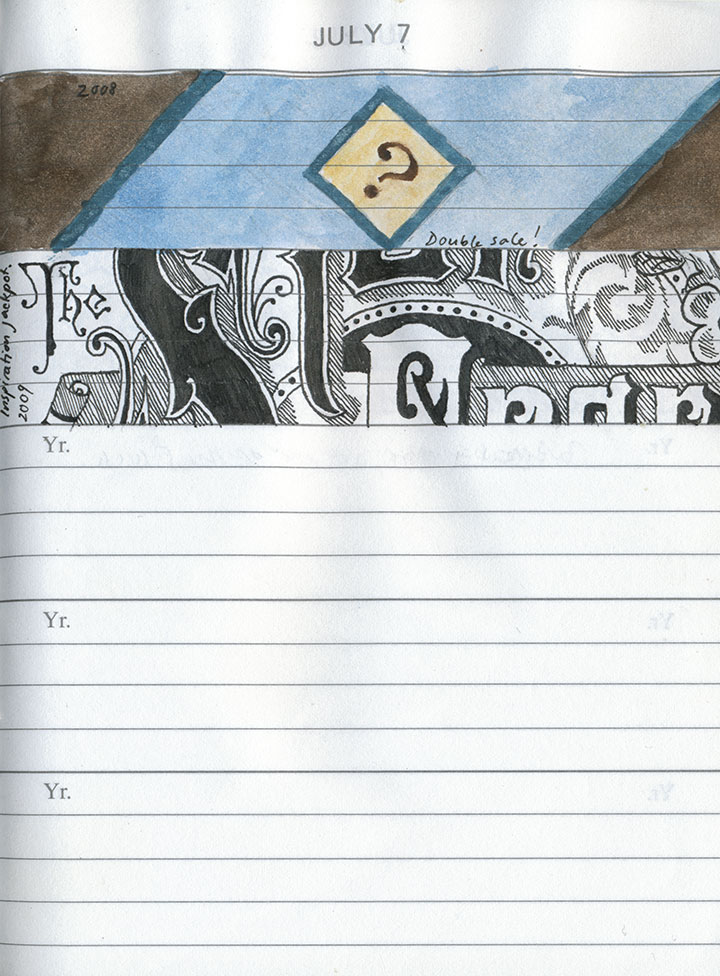

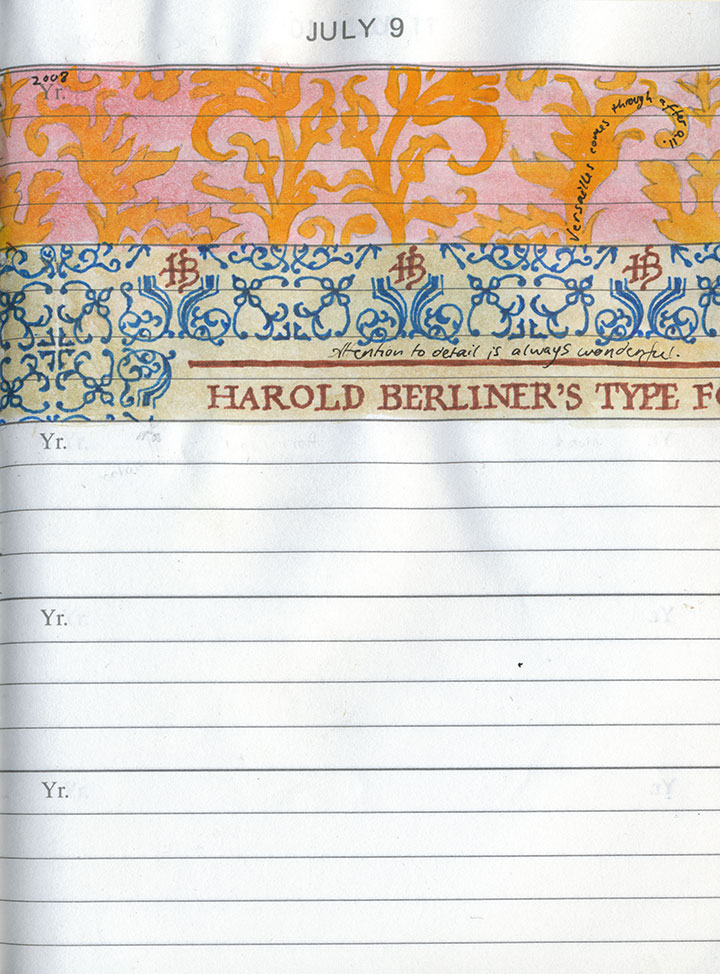

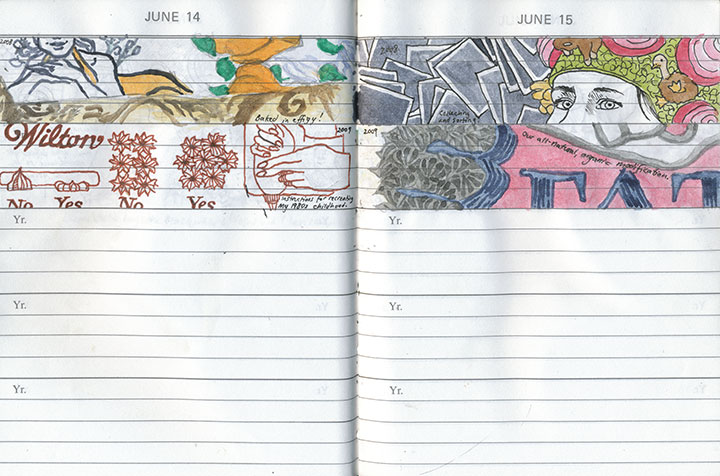

Sarah and I were both inspired to start five-year journals of our own, but I decided to turn mine into a sketchbook. I loved the idea and the challenge of documenting each day with a tiny, panoramic image.

Almost every drawing depicts something mundane, even trivial; it might be a sliver of that day’s activities, or just a snippet of an object that caught my eye. I’m almost never specific in the brief phrase written in each space—in fact, already I find myself forgetting what I was referring to when I go back to look at past entries. When I do remember what I was talking about, though, each illustration triggers my memories better and more richly than any of my photographs or writing can.

But that’s not the point of this project; this was never meant to be a detailed journal of my every thought or action. Instead, I’m trying to remind myself to really look at the world around me, and to live in my own present.

Now, exactly two years into the project, the same type of narrative I found in Claire Anderson’s diaries is already beginning to emerge. The drawings serve as a sort of flip-book; as one pages through the journal my personality, tastes and interests come to life, and the result is a more complete picture of myself than I ever could have come up with consciously. And an interesting by-product of all of this is the sometimes-unwitting documentation of the current era—this book might prove to be useful in other ways, someday.

The really curious bit is how the book is both intensely personal and completely ordinary. There isn’t a single image in there that I couldn’t share with a total stranger (no nudity, no embarrassing missives, no dirty laundry, etc.), and yet I’ve only actually shown it to a handful of people. I’m not sure why that is, but now that I’ve gone “public” about it I’m sure I’ll post occasional excerpts from here on out.

At the very least, maybe this will tighten the screws on my discipline a bit. Sarah and I learned quickly how difficult it is to keep a daily journal like this, whether in words or pictures (I doff my hat to Mrs. Anderson’s habits)—it’s all I can do to keep up with it, and I’m often playing catch-up. But now that I see how worthwhile the effort has been, I find myself excited for whatever tomorrow brings.

And isn’t that the whole point?

Wishing you a happy New Year full of wonderful events and tiny moments worth savoring—however you choose to remember them.

December 10th, 2009

After nearly a year, image-gathering for my Mt. Rainier artist book is finally coming to an end, and I’m starting to make the final illustrations. I have a huge stack of sketches, scribbles and recorded data, and thousands upon thousands of photos to sift through. This month and next are scheduled for the all-important (and terrifying) process of Figuring Out How the Heck to Make It Work—physical mock-ups, final compositions, text-writing, etc. But before I could move on with a clear conscience, I had one last far-away location to cross off my research list: Portland. And for some reason, the stars just weren’t aligning for me.

My first attempt this summer was also my first-ever trip to the city, so I had to location-scout with a blank mental map—and when I finally found what I was looking for, it was too hazy to see anything anyway (hence the dotted line where Rainier should be). Since Portland is 140 miles away, I couldn’t just try again any old time I pleased. As the months went by, I became increasingly frustrated—the location I visited over the summer (Larch Mountain) is inaccessible in the winter, and although I had another spot in mind, my schedule and the weather (which was way harder to pin down than an open travel day!) just couldn’t find anything in common; the last few months have been typically Northwestern, with plenty of rain, fog and drear for a volcano to hide behind. Finally, last week, it seemed I had my chance. T-town was socked in with pea-soup fog, but since the previous day had started the same way and ended in sunshine, I decided to go for it. As I cleared the Puget lowlands and the fog lifted, I caught crystal-clear glimpses of Rainier to the east as I went, and my confidence rose. I wouldn’t know for sure until I got there, but the sunny weather seemed like it would hold. I made good time to Portland, wound my way up to Council Crest Park, jogged up to the viewpoint and faced north—

—and saw that Mt. Saint Helens didn’t get the memo. It had its own private weather system blocking Rainier from view.

It was a long drive home that night.

The last few days were torture. The weekend taunted me with sunny mornings and cloudy afternoons (good thing I didn’t take the bait), and the perfect weather went untested Monday and Tuesday while I taught class and kept appointments instead. By Tuesday night, I was sure I’d missed my last chance, and resigned myself to leaving Portland out of the book. But yesterday dawned cold and flawlessly clear, and I was astonished to find my calendar empty. I left the Tailor an incoherent voicemail at work (“I’m going right now! I’ll be back tonight!”) and jumped in the car. Exactly two hours and twenty-three minutes later, this is what I saw:

That’s St. Helens in front, with Rainier just peeking around her left shoulder.

And here’s the illustration that resulted from all this work:

And in case I had any doubts about one image being worth all this trouble, Portland offered me a little bonus—a compositional jewel that I could never have dreamed up on my own:

The City of Roses was still, impossibly, in bloom.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)