Fabric Feminists, part two

By now you’ve figured out that I have a thing for stitched lettering; and since I’ve already rambled on ad nauseum in the last post, I can keep this one a little shorter.

And anyway, I somehow neglected to take any process photos for two of these. Oops.

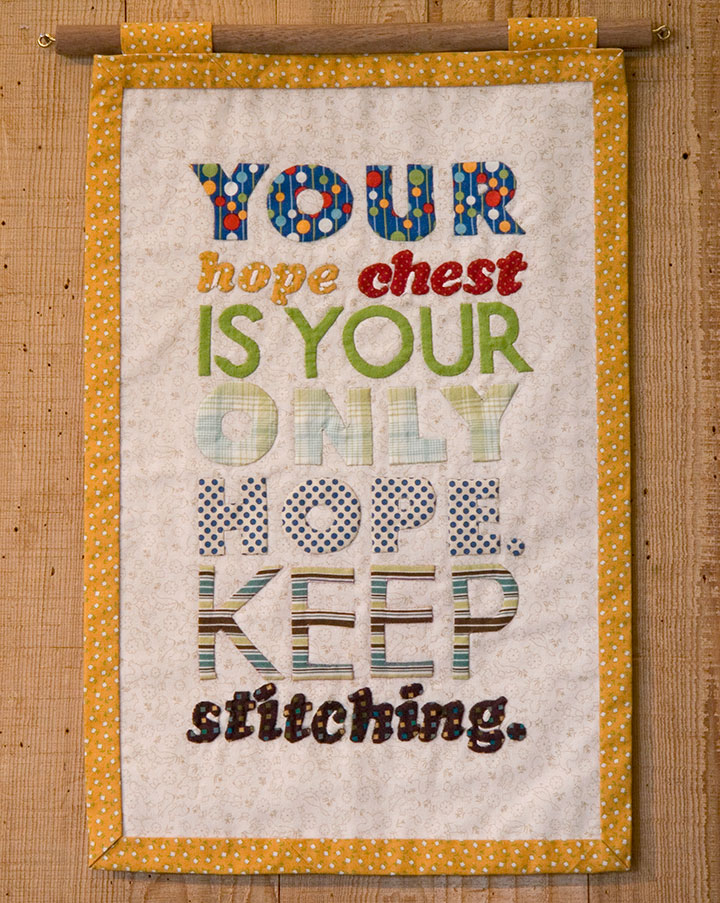

The knitted broadside was such a success that I decided to try branching out into other textile media. For Broadside No. 4, I took a shot at appliqué—something I’d never done before. Hand-sewing all those fiddly little pieces of fabric ended up being just as daunting as cutting a steek.

The hard work was oddly fitting for the concept: historically, a traditional wedding trousseau would have been sewn by a girl or young woman, in hopes of one day becoming a married woman with a home of her own. By the time she reached young adulthood, a woman would have spent years creating dozens of hand-sewn garments, household linens and other useful textiles, all gathered and stored in her “hope chest,” awaiting the day she would become a bride.

The thing is, back in the days when women couldn’t vote, or own property, or head a household, marriage was a woman’s only shot at independence or social status. (Hence the snark.)

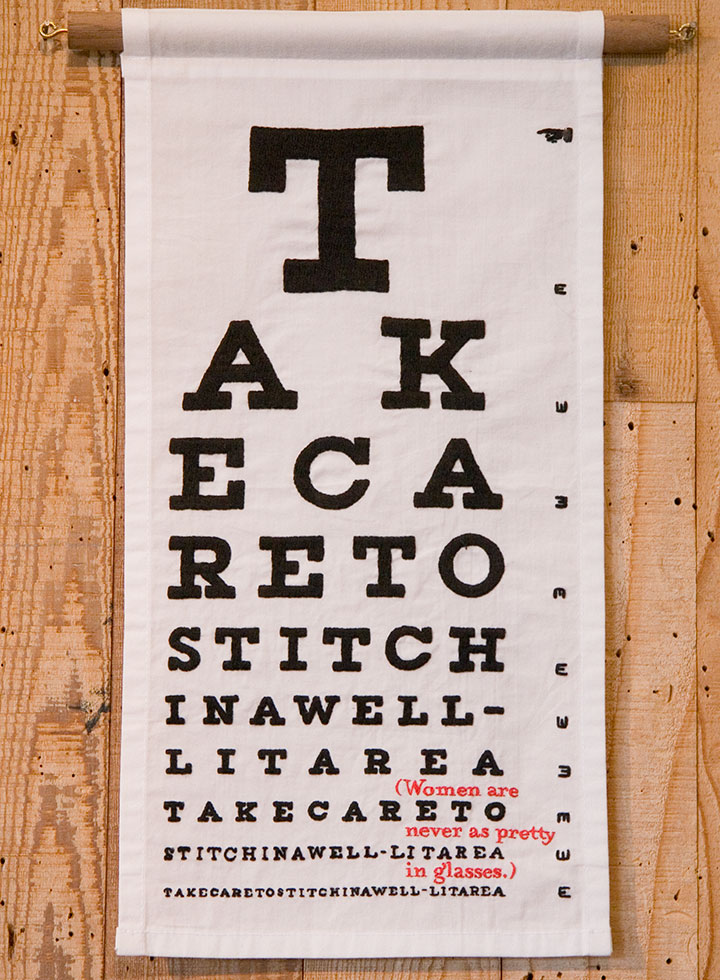

For the others, I turned to the original, old-school ancestor of fabric paint: embroidery. The method fit the madness this time, too, as I spent what seemed like a century hunched over and squinting, hand-stitching an eye chart…

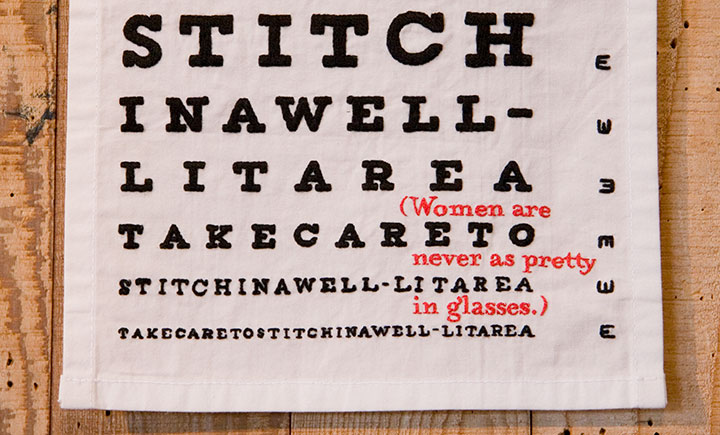

…complete with something to read between the lines.

This one gets personal. As a glasses-wearing gal myself, I happen to disagree with the statement—but I’ve actually heard these very words spoken by a woman. She wasn’t wearing glasses.

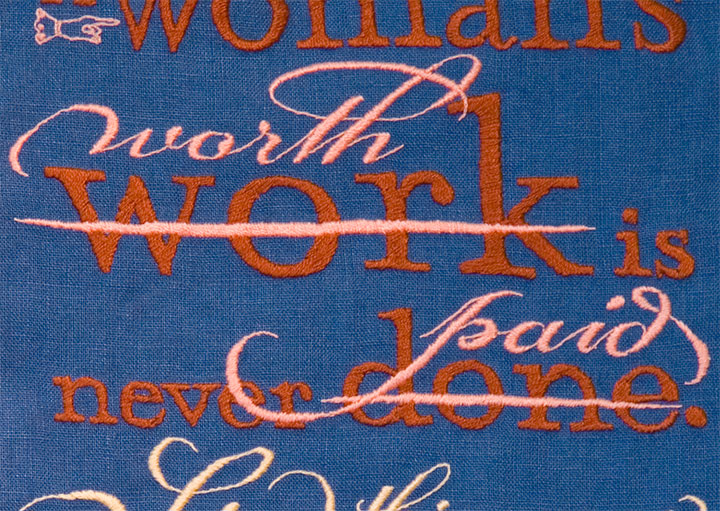

Last of all, I got to thinking about how men who sew for a living are called tailors—and women who do the same are called seamstresses. And how the two terms don’t quite add up to the same meaning.

Despite what the scornful quipping of the text might indicate, I had the most gleeful fun with this one. Unlike knitting, which confines the designer to a grid, or appliqué, which can only push the detailing so far, embroidery has almost limitless possibilities. So I went nuts with the tails and ligatures and dingbats, simply because I could. I love that about embroidery—it’s as flexible as I need it to be, and as fluid and crisp as the printed page.

All that was required was the patience to work each letter by hand. But it didn’t feel like patience—it felt like meditation.

It’s surprising how easy it is for embroidery to mimic letterpress. And watching “wood” type pop up from the fabric, rather than punch into paper, is a mighty satisfying sight.

Uppity notions aside (no pun intended), the Women’s Work broadsides are a fun way to slow down and take a break from what I normally do in the studio. But as I wrap up each one, I find myself hankering to get back into the print shop. By comparison, setting type and drawing letters suddenly seems like speedy work!

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)