Blog

August 14th, 2009

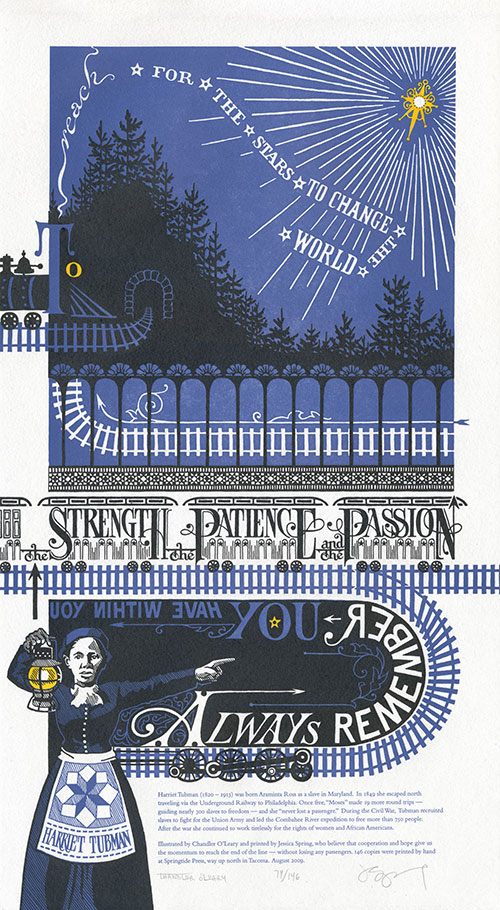

For nearly a year now, the Dead Feminists series has given us an outlet for both our aspirations and frustrations. For every social and political victory, there follows a reminder of how divided we are as a culture. We were so proud to see Victory Garden become a part of a nation-wide movement toward sustainability—but a movement and a majority are not the same thing. We are delighted whenever a customer tells us that Prop Cake is meant for a wedding gift—but are heartbroken by the reminder that for many people, the gesture can only be symbolic. Yet through it all we remain optimistic that art can make a difference—that a bright future is out there, somewhere, and that we can help find the way to it.

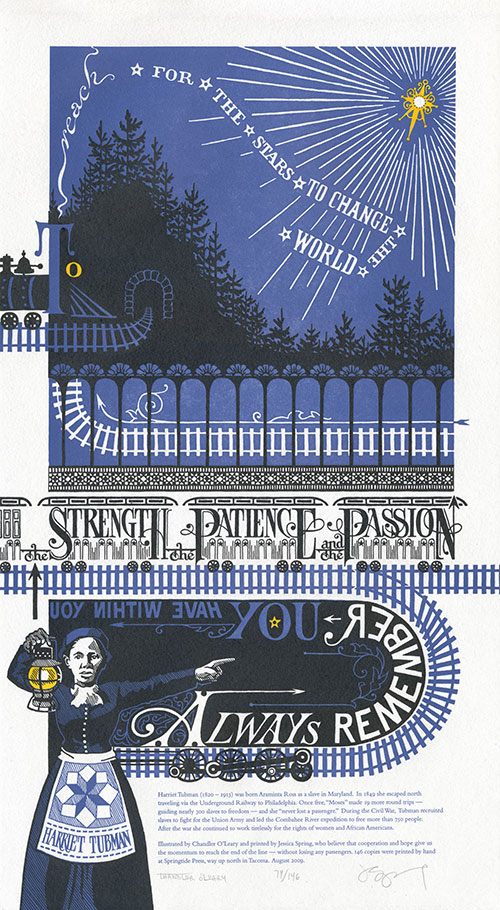

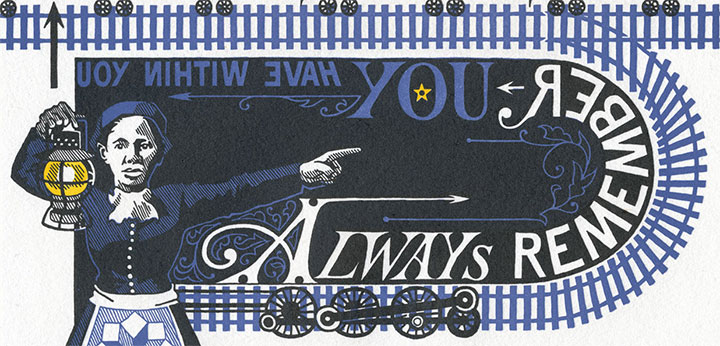

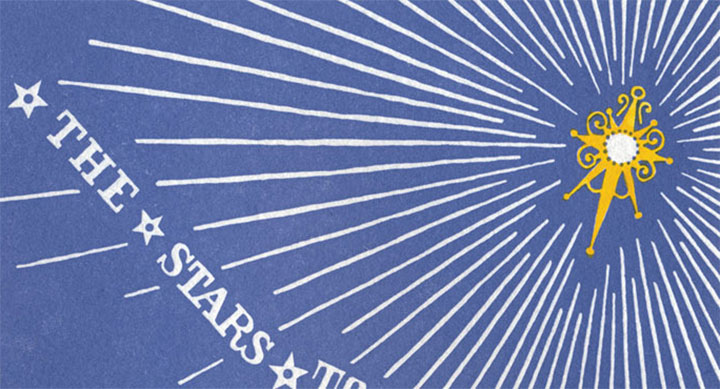

Always remember you have within you the strength, the patience and the passion to reach for the stars to change the world.

— Harriet Tubman

This is why we chose Harriet Tubman for our latest piece. There are so many pressing issues vying for our attention—war, the economy, healthcare, the environment, transit, equality, etc.—that we couldn’t choose just one. So we decided to focus on the journey itself. For all the ground we’ve gained in our country’s short history, we have a long, long way to go—and the only way we’ll get there is together. Harriet Tubman knew that when she fought for freedom and civil rights, and she devoted her entire life to the idea.

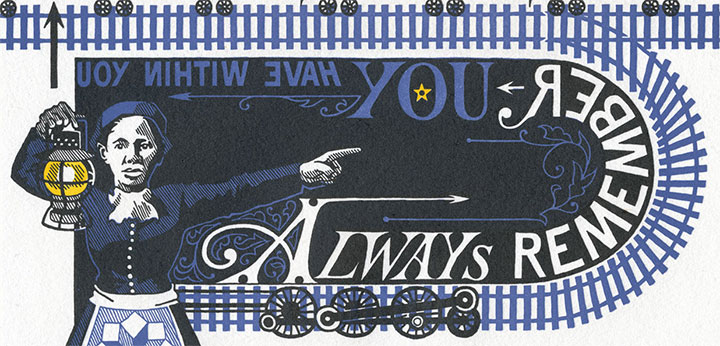

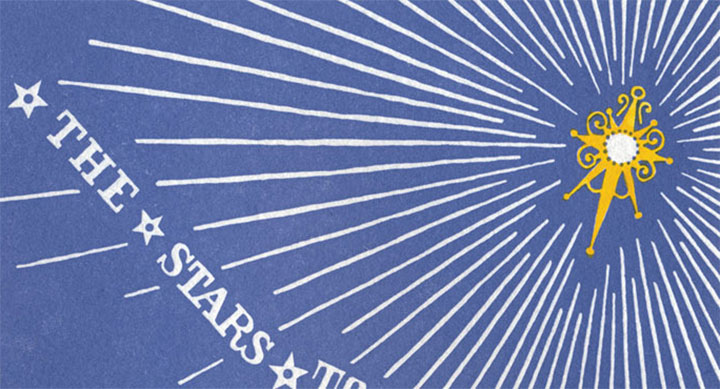

So here, submitted for your approval, is End of the Line. As always, everything—from the illustrated lettering to the letterpress printing—is done completely by hand. This time, though, we’re asking you to flex your reading muscles a bit: to symbolize the difficult journey faced by anyone with a great task, we made it somewhat of a challenge to read.

Don’t worry, though—Harriet is there to guide you. Just follow her lantern, and you’ll find the right path. If you lose your way, just look for the Drinkin’ Gourd.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

End of the Line: No. 5 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 146

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press and hand-colored with watercolor. Each piece is printed on archival, 100% rag, recycled paper, and signed by both artists.

Colophon:

Harriet Tubman (1820 – 1913) was born Araminta Ross as a slave in Maryland. In 1849 she escaped north traveling via the Underground Railway to Philadelphia. Once free, “Moses” made 19 more round trips—guiding nearly 300 slaves to freedom—and she “never lost a passenger.” During the Civil War, Tubman recruited slaves to fight for the Union Army and led the Combahee River expedition to free more than 750 people. After the war she continued to work tirelessly for the rights of women and African Americans.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, who believe that cooperation and hope give us the momentum to reach the end of the line—without losing any passengers.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

August 12th, 2009

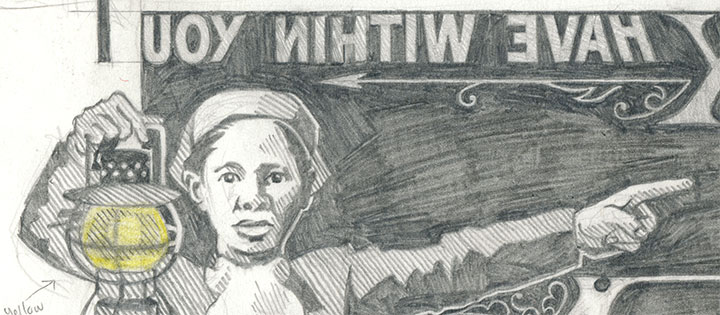

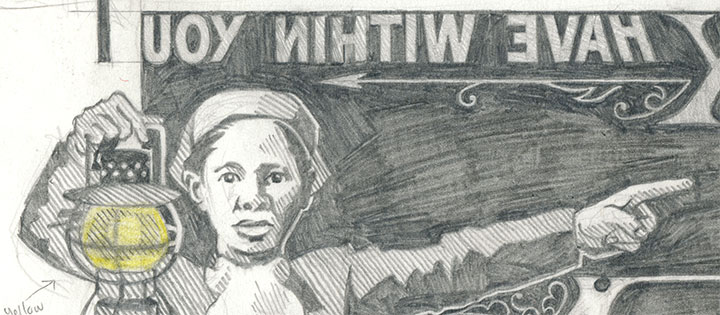

Jessica and I are almost ready to unveil the next Dead Feminist broadside! The ink is drying as I speak, so End of the Line will be available this Friday, August 14. For now, this is just a taste. Brush up on your mirror-reading skills, because this one is going to be a challenge. Stay tuned!

May 16th, 2009

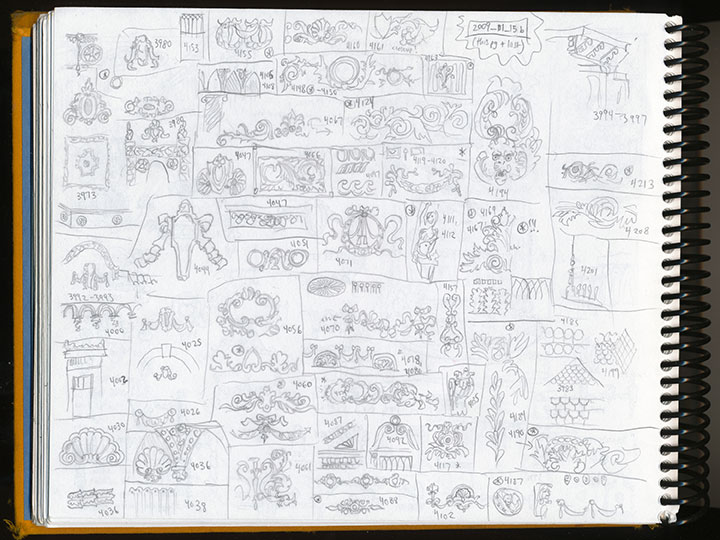

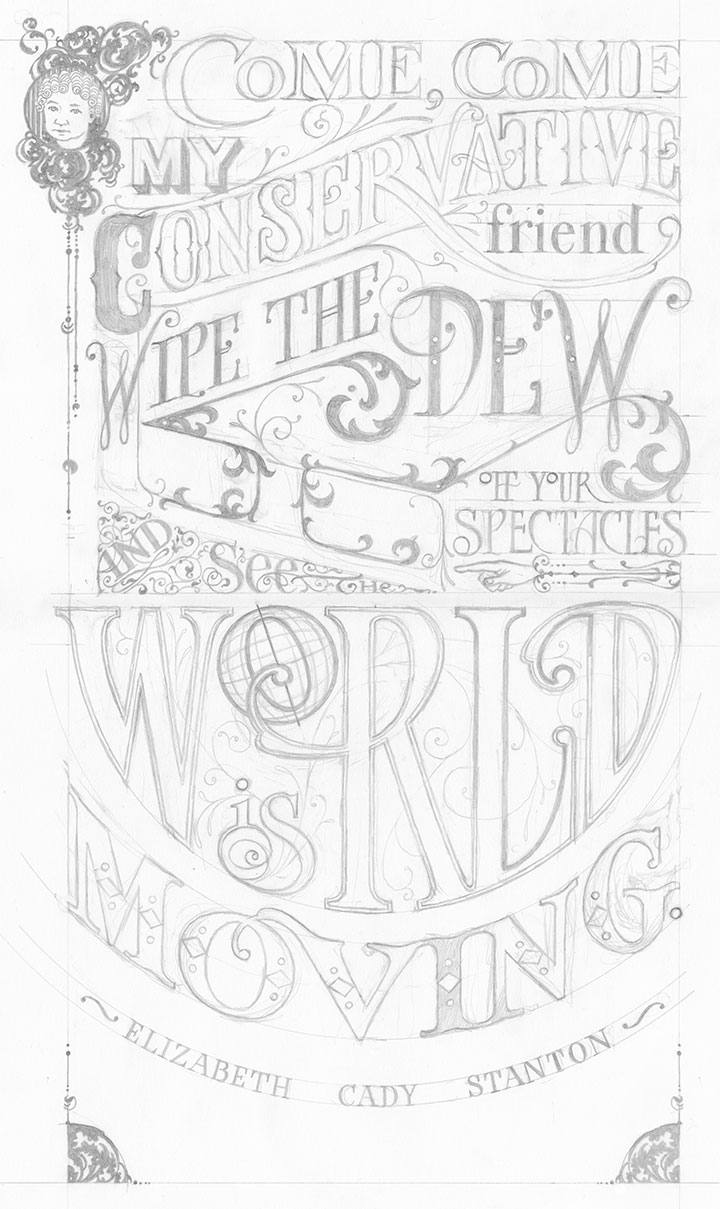

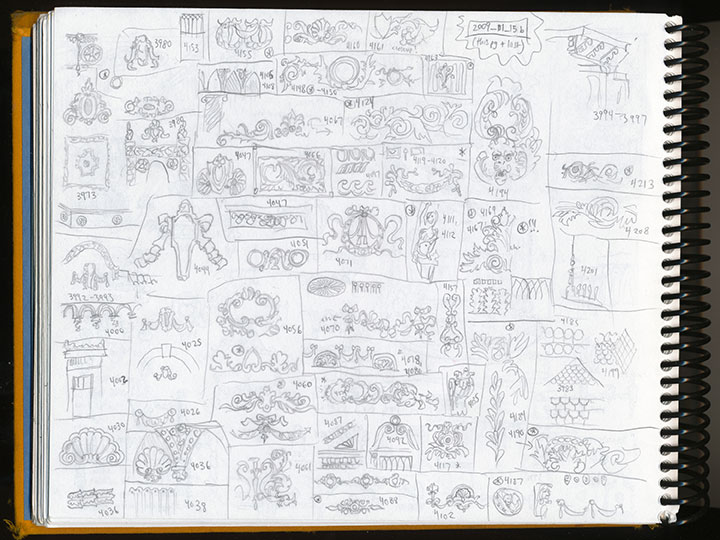

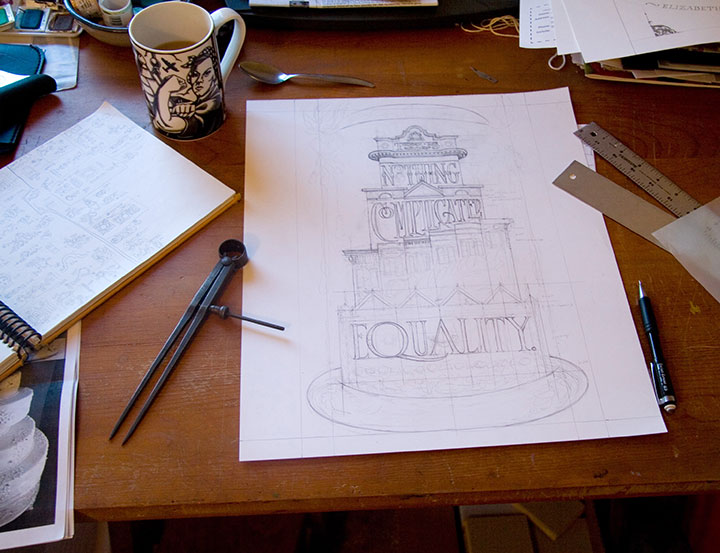

When it comes to letterpress printing, process is everything. And since that process is not always evident in the final product, I thought I’d share the technical aspects of the Dead Feminists series. Now, as I said in the last post, letterpress printing is traditionally done using metal or wooden type—or in the case of the photo above, relief images cut into type-high (.918 inches in the US and UK, in case you wondered) blocks. What Jessica and I have been doing, however, ain’t your grandpa’s letterpress. Thanks to a fairly new technology called photopolymer, we’re able to create our own relief plates right in the studio, without having to carve a block by hand or etch a plate with nasty chemicals. Photopolymer has also created a bridge between the traditional print shop and the modern digital world—as you’ll see in a moment. As far as the Dead Feminists go, Jessica and I still have both feet firmly planted in the traditional world—we just dip a toe into the digital realm now and again. Here, let me explain.

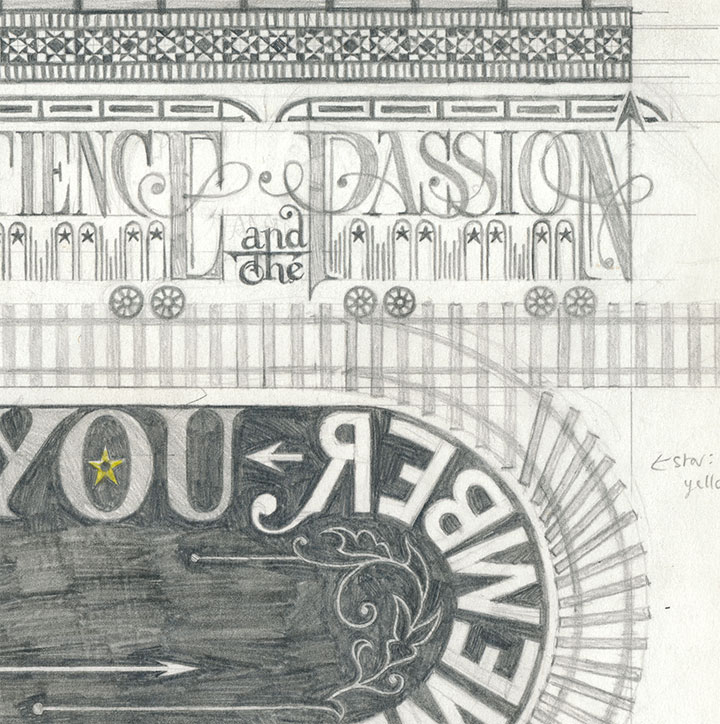

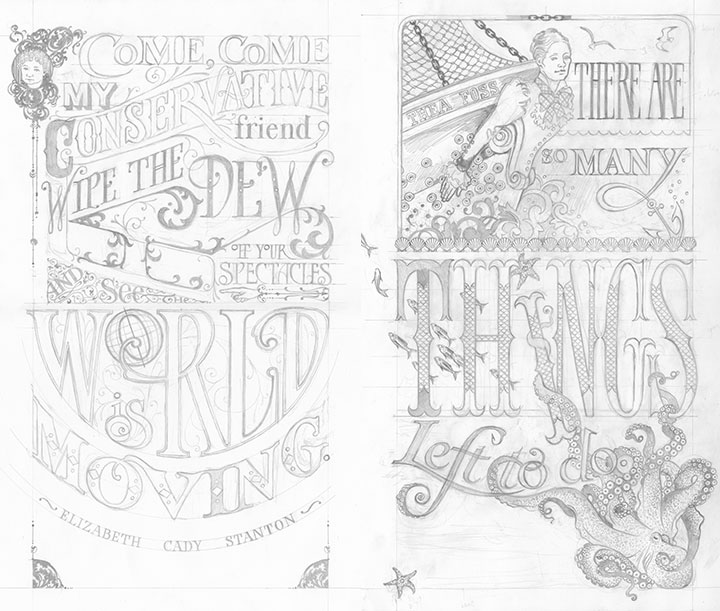

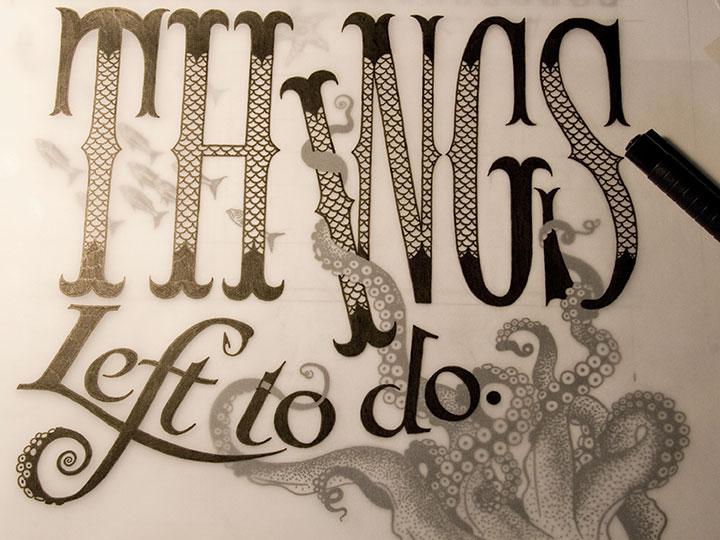

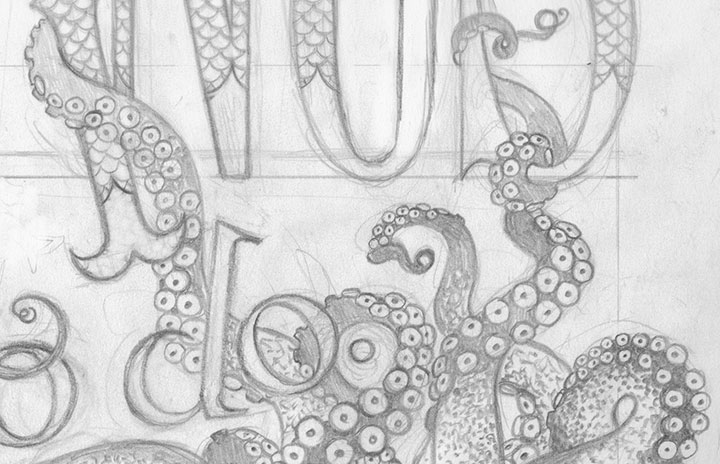

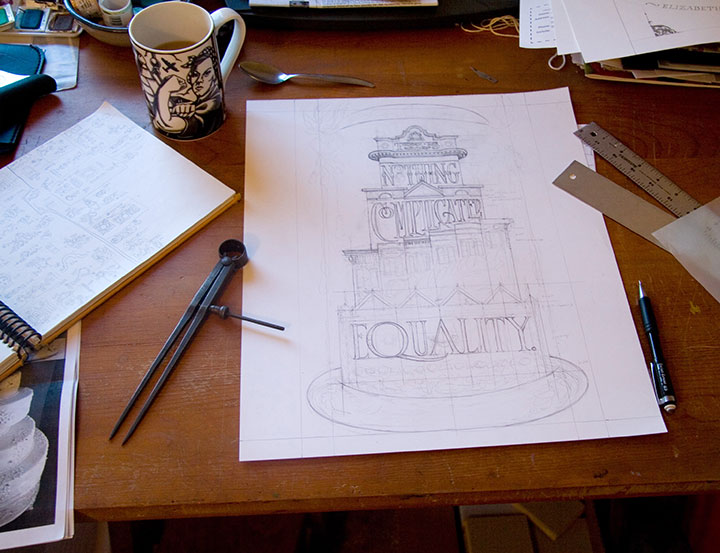

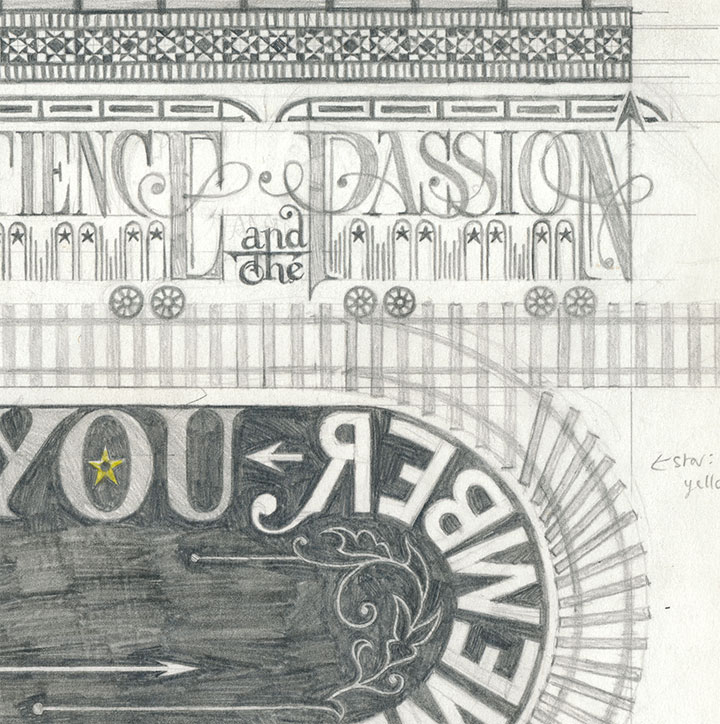

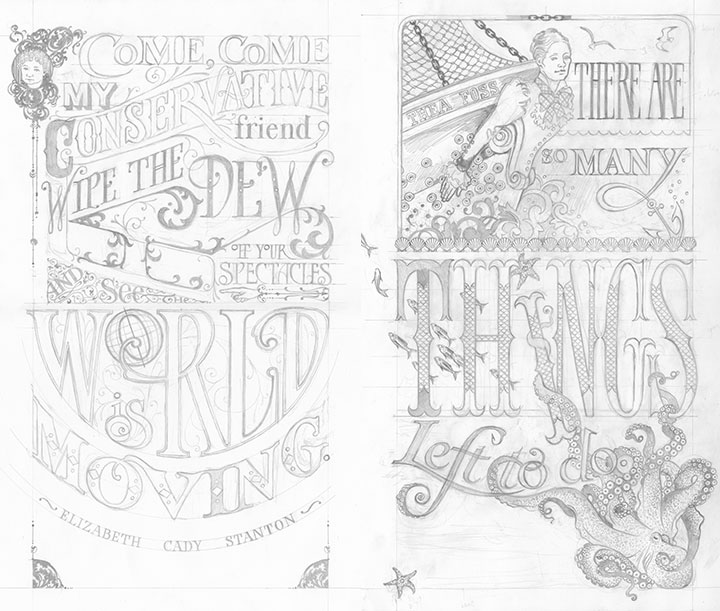

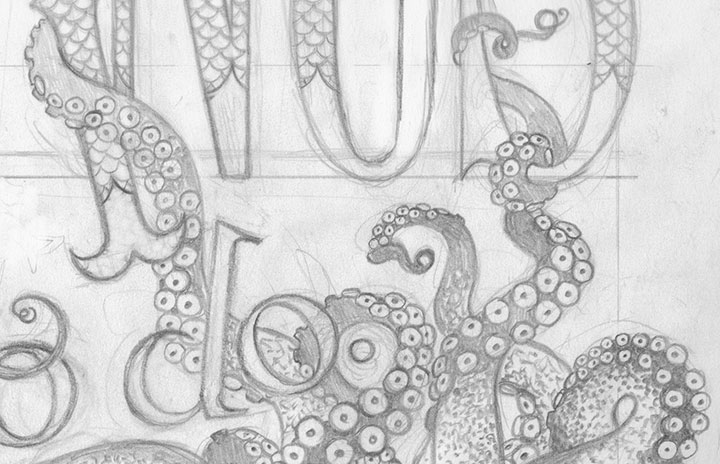

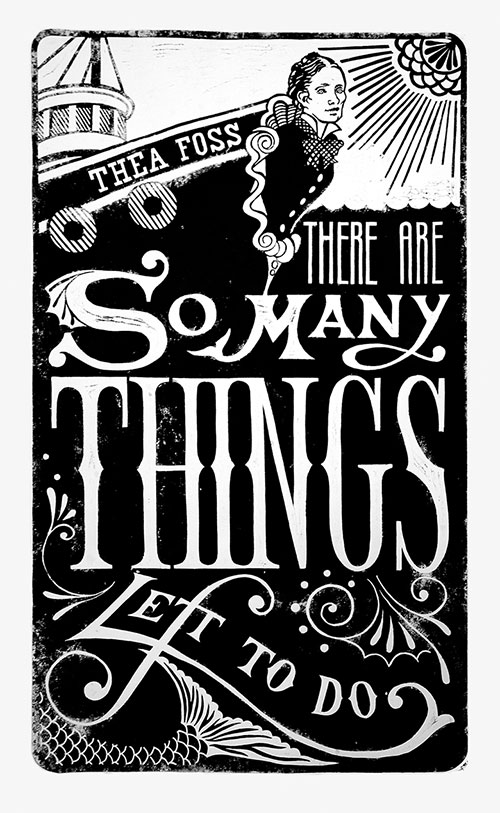

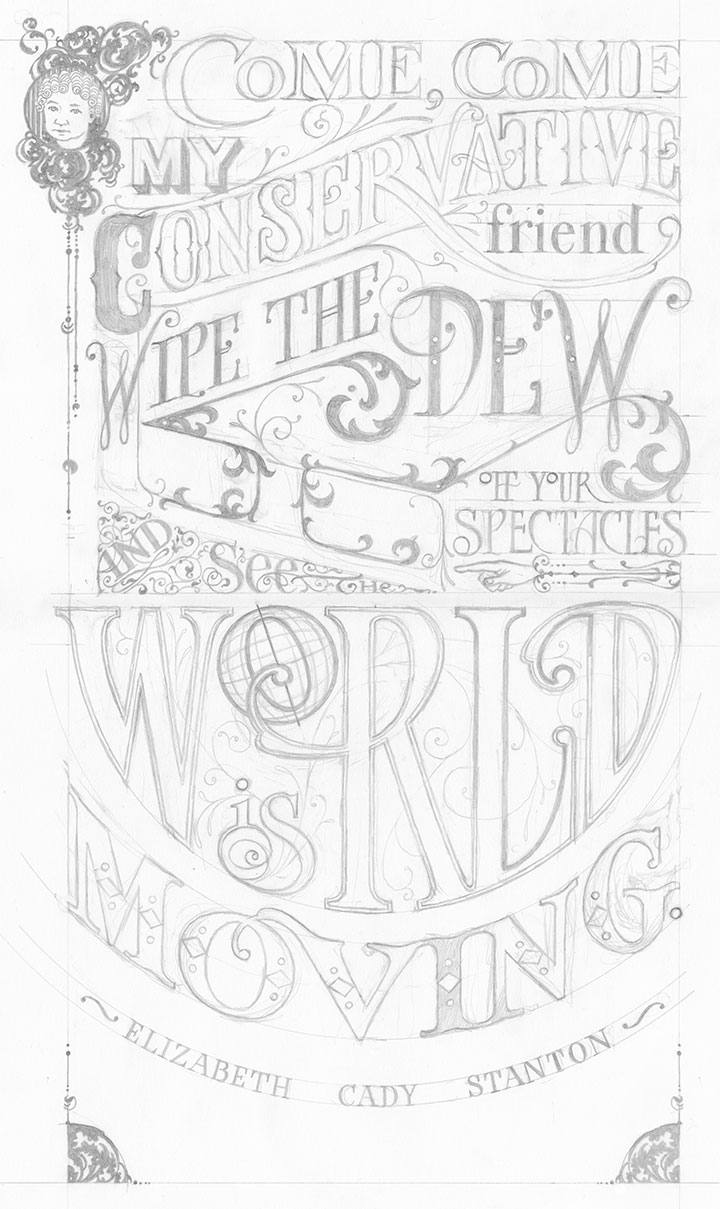

This is how it begins for each print: a pencil drawing, at full size. This is the stage where I not only design and illustrate the piece, but also start thinking about color choices: what the colors will be, what element will be which color, where the colors will overlap, how to make things work logistically. Now, this pencil layout isn’t enough to make a plate; for the photopolymer process to work properly, I have to translate the sketch into a solid black-and-white ink drawing.

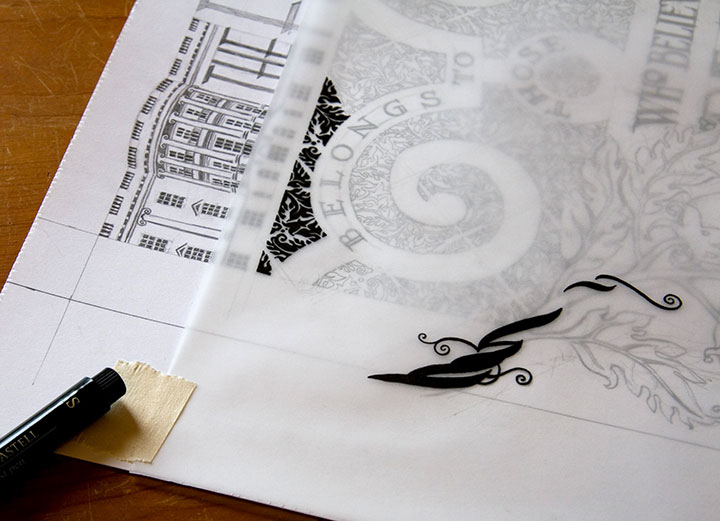

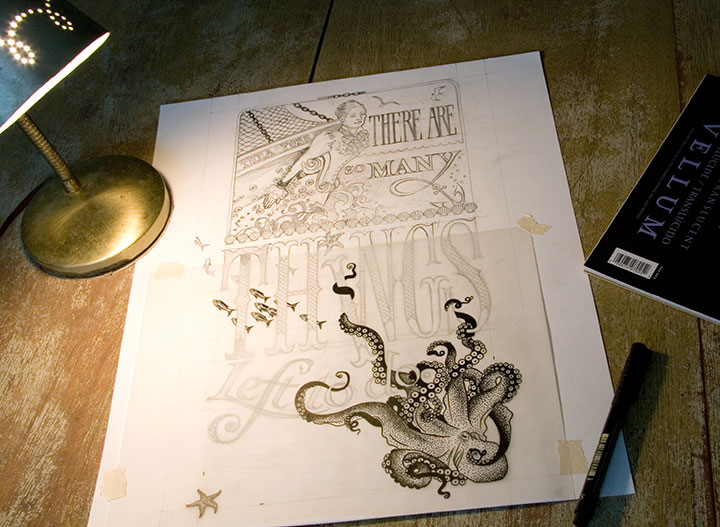

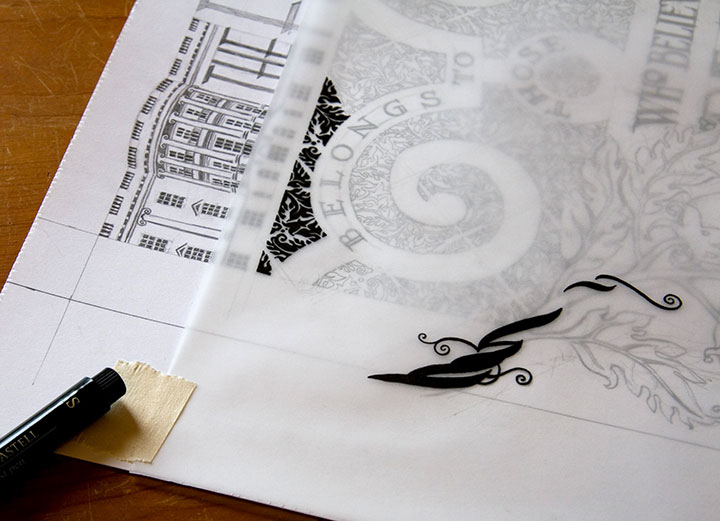

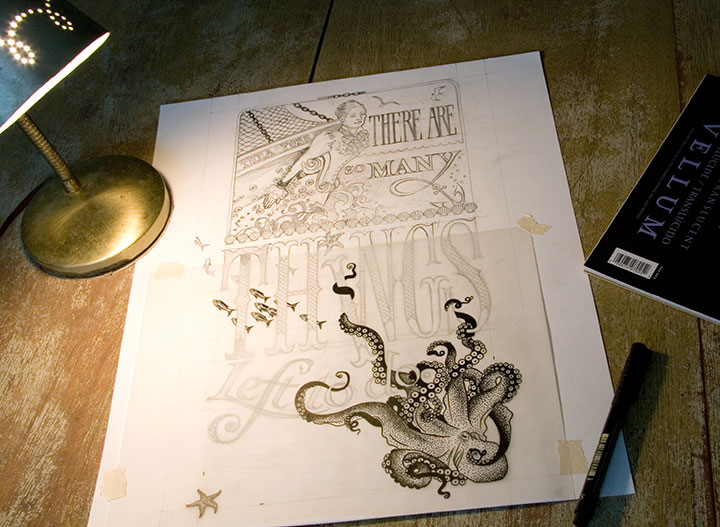

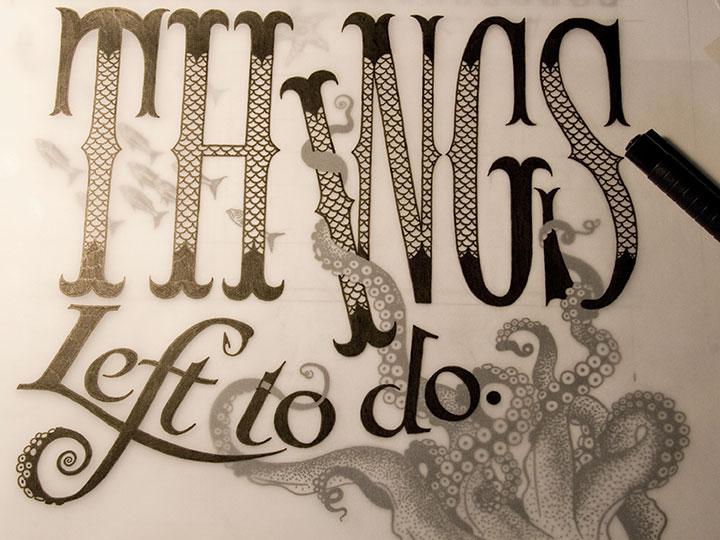

After everything is pencilled in, I lay a sheet of vellum over the drawing and trace everything in ink.

Since each broadside is printed in two colors, each color means a separate run through the press. So as a result, I had to trace each color separately—being careful to stay as true as possible to the original drawing, since the colors had to line up exactly on press. If you were to line these two color separations up, on top of one another, you’d see how the colors will interact in the final piece.

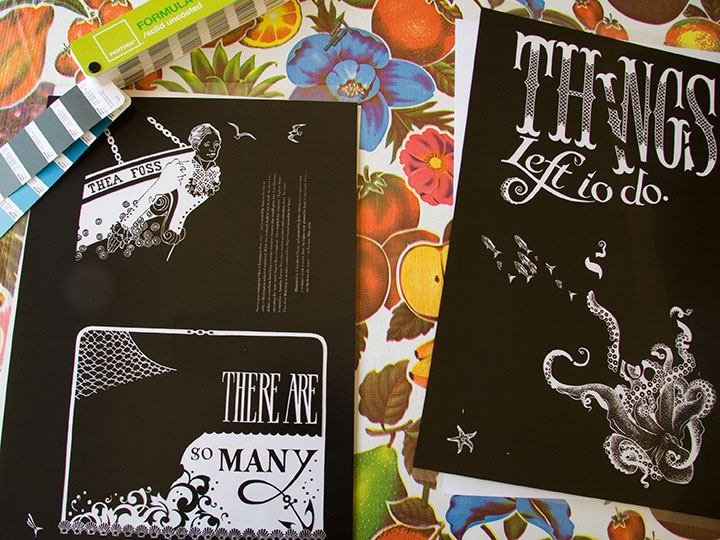

Here’s what I mean. You can see the separation that will become the grey color in Tugboat Thea here, laid directly over the inked octopus below. This is definitely the old-fashioned way of doing things; there are plenty of digital methods of color separation. I guess I just prefer the physical connection between the pen and the hand—even despite the greater risk of screw-ups (as you can see if you look closely at the word “to” above).

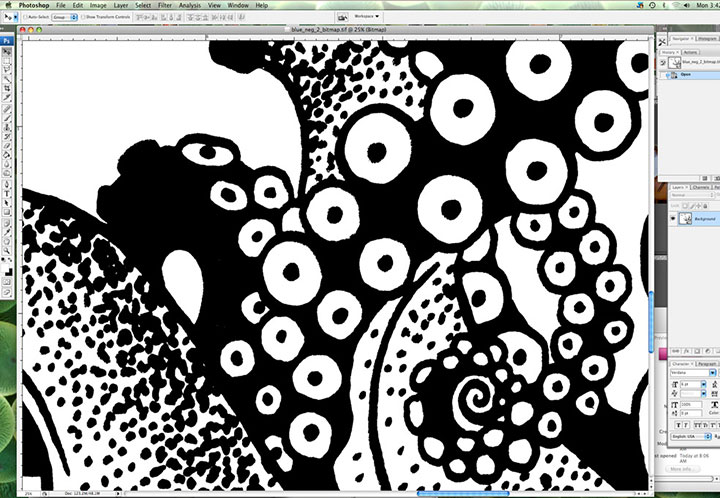

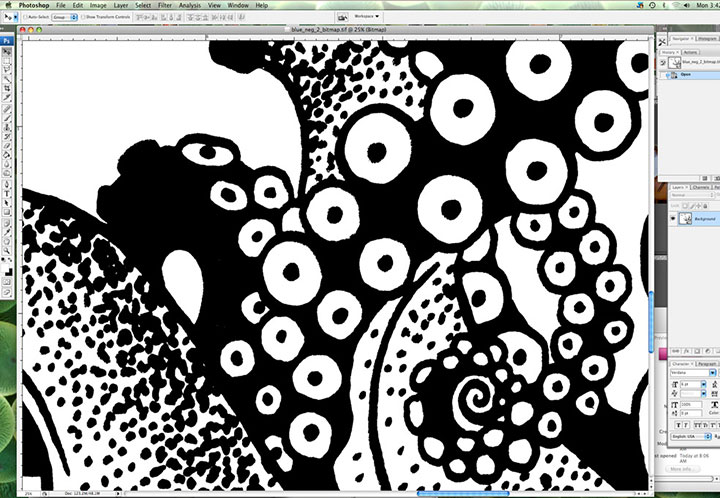

Here’s where I dip that toe into digital waters. Once I’m finished inking, I scan the finished line drawings at a super-high resolution and load them into Photoshop. This is where I clean up any mistakes (ahem) and convert the drawings into bitmap (pure black and white, with no grey) files. Jessica sends me her written colophon, and I set the text digitally. Then I export everything to the proper file type, and send the files to a local service bureau to have film negatives made. So now we’ve gone from analog to digital and back again.

Here are the negatives for Tugboat Thea; grey separation on the top half of each one, teal on the bottom. As you can see, there aren’t any right angles in the bottom half (octopus) of the teal separation, so if you look closely you can see the little tick marks I added (above and to the right of the starfish) to aid with color registration. Those marks line up with a grid etched on the metal base we use to lock up the plates on press; once we had the plates exactly where we wanted them, I simply shaved those little tick marks off with an Xacto knife, so they’d no longer print. Real slick.

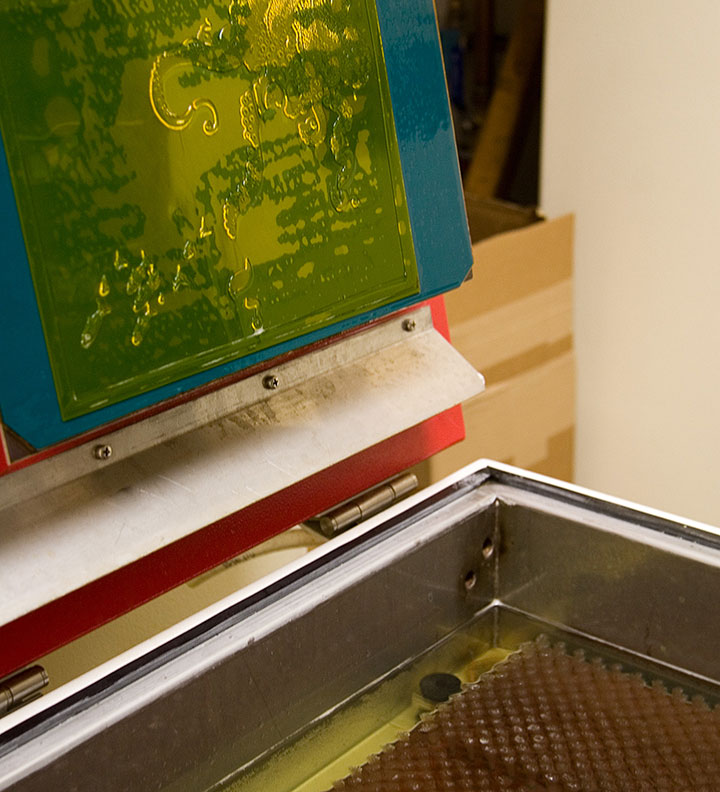

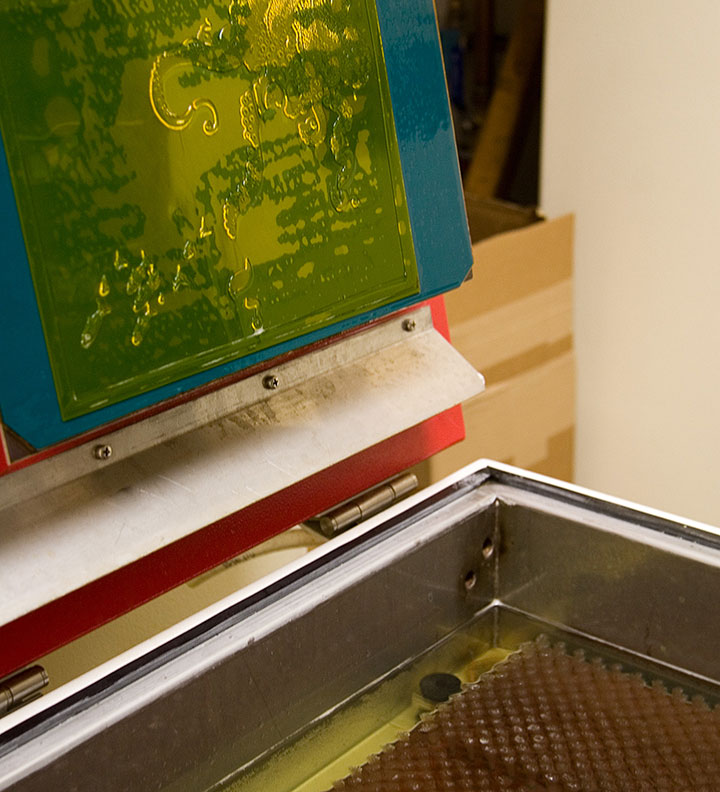

Anyway, photopolymer is a light-sensitive plastic that works just like making a contact exposure in a darkroom does. First I take a negative, place it face-down on an unexposed plate, and load both pieces onto the exposure tray of Jessica’s platemaker (which looks remarkably like an Easy-Bake Oven).

The negative is held flush with the plate by a layer of plastic and a vacuum system; the plate is exposed with UV light (some DIY enthusiasts also accomplish this using glass and a bright, sunny day, but photopolymer is awfully expensive to use in sketchy experiments in the cloudy Northwest).

Next I place the exposed plate in the wash-out unit, where it is scrubbed gently with soft bristle brushes in a tank of cool water. Everything that is exposed is hardened enough to resist scrubbing, while everything else dissolves away. (And turns the water a sickly shade of yellow. Mmmm….plastic byproducts. Still, it’s less toxic than many other printmaking techniques.)

What we’re left with is a raised plate ideal for relief printing. The real benefit of photopolymer is that it can reproduce nearly any image, and can hold an incredible amount of detail. I can transfer my drawings directly to the plate, without adding the laborious step of carving the image into wood or linoleum (backwards!), or etching copper with acid, for example. It’s not exactly an economical option for letterpress printing, but the results can be exquisite, and the possibilities are nearly endless.

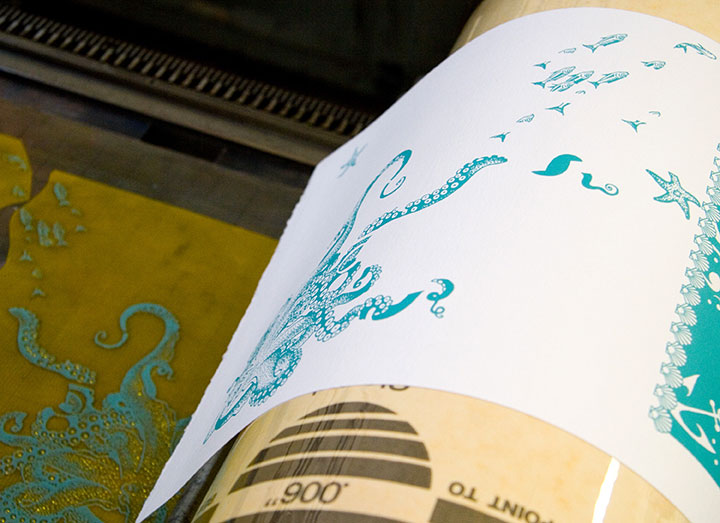

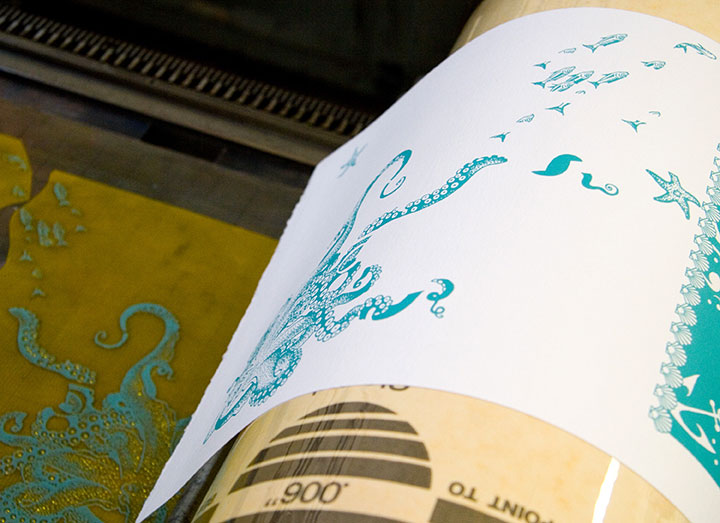

Here’s our new octopus plate on press, all inked up and ready to print—it’s stuck to that gridded base with removable adhesive. The thickness of the plate and base together add up to exactly .918 inches. Ah, precision feels good.

And here’s how it looks on paper.

Here you can see the registration between the colors. This is the hard part—I’m sure that despite my best separation efforts and useful tick marks, Jessica is ready to tear her hair out whenever she sees what insane registration issues I’ve thrown at her this time. She’s not a master printer for nothing, though—tiny, 9-point colophon type? No problem! Large, solid color blocks? Bring ’em on! Exacting registration with no margin of error? Sigh. Just get those plates locked up, will you?

Actually printing these broadsides is where all our careful planning and preparation goes right out the window. We can sketch and plot as much as we like, but many of our artistic decisions end up being made on the fly, right on press. Here Jessica is mixing ink for Prop Cake, according to some choices I suggested in our handy-dandy color recipe book.

You can see our original draw-down (color test) in the upper left corner. So far, so good.

The orange turned out exactly as we’d hoped, but when we started printing the pink separation, we hated the result. What looked so good in the draw-down lost all its contrast in the print. It was awful, trust me.

So Jessica changed the color right on press, until we were happy with it.

Here’s the finished product, all lined up in the drying rack.

If lining up the color areas is the hardest part of printing, keeping an eye on the ink consistency was probably the most fiddly. We’re using a very unusual paper for the series—one made from recycled clothing—that is extremely “thirsty.” Not only are there inconsistencies in the paper that can throw off the overall quality of color; but we had to add ink to the press after every fourth or fifth print. As you can see, this is a pretty organic process—lots of variables, small corrections and compromises along the way. (And a whole lot of cursing and starting over.)

All of this is par for the course for a letterpress project—it’s an exacting, sometimes frustrating process, but that’s what I love about it. And the finished product … well, it’s like nothing else. Ah, letterpress, how I love thee.

Now if only it didn’t require several metric tons worth of equipment…

May 14th, 2009

Holy cannoli, everyone! I’ve only just now come up for air—I’ve been buried under invoices, subscription forms, kraft mailers, and email print-outs, and Thea’s face is repeated all around me as reserved copies are spread all over the studio. Since I posted her here on Tuesday night the orders have just poured in, and over three-quarters of the edition is spoken for already. And Prop Cake is disappearing fast, too; we’re down to our last handful. Wow—just…wow. Thank you all so, so much.

Since Thea and her fellow Dead Feminists have left T-Town to be shipped all over the country (and to lovely Canada, France, Switzerland and the UK, too!), I thought it appropriate to share some of the things Jessica and I talked about at TAM the other day with a wider audience. Now, normally my paralyzing fear slight nervousness while speaking to a crowd manifests itself by wiping my memory clean immediately after I give a talk. It’s a very annoying thing, not being able to remember what you just said, but it happens all the time. I guess I’m fortunate that my phobias don’t show up as a quavering voice or profuse sweating (so nobody ever believes me when I say I get stage fright), but selective amnesia isn’t much of a fair trade for fake confidence! But this time, weirdly, it didn’t happen—I remember almost everything, and I think it’s because I wasn’t alone. (Jessica, I reckon that means you’re doomed to be my speaking partner from now on!) So to make sure my memory stays put, I’m setting it down here for the record. (By the way, since there’s rather a lot to say on the subject, I’ve decided to break it into two posts.)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

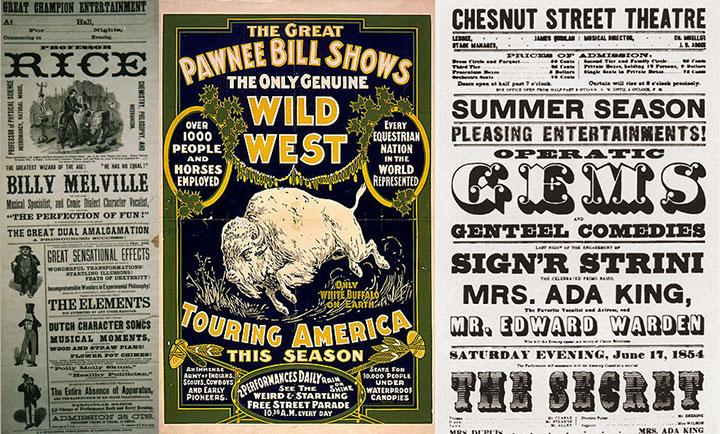

Before I get into the technical details behind our series, I should probably share a little background information on letterpress and the art of the broadside. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the process, letterpress printing refers to a type of relief printing, where pressure is applied to a piece of paper placed over a raised form that is covered with a thin layer of ink. This pressure transfers the inked image onto the paper, and can be repeated to create a batch, or edition, of prints. The form can be a carved block of wood or linoleum; a raised plate made of magnesium, photopolymer (plastic) or other materials; or as the term letterpress implies, movable type made from metal or wood.

The innovation of printing words from individual letter blocks that can be rearranged and reused was actually invented by the ancient Chinese (seriously, what wasn’t originally invented in China? We owe those folks a whole heap), but the process that evolved into modern letterpress was most famously perfected over 500 years ago by Johann Gutenberg, of Gutenberg Bible fame. By the first half of the twentieth century, when more modern commercial printing came along, it was still common for printers to perfect their layouts using movable type and relief-cut images on a proof press (such as Jessica’s Vandercook below). They’d then use the resulting print to make more sophisticated plates for their more efficient and advanced commercial presses.

Jessica printing “Prop Cake” on her Vandercook Universal One press

As commercial printing became more streamlined, the cylinder and platen proof presses (see photo above) fell out of vogue, and eventually were no longer manufactured. Artists quickly saw their potential, however, and have adopted letterpress printing as an art form—using, refurbishing and maintaining this antique equipment to create original works of art.

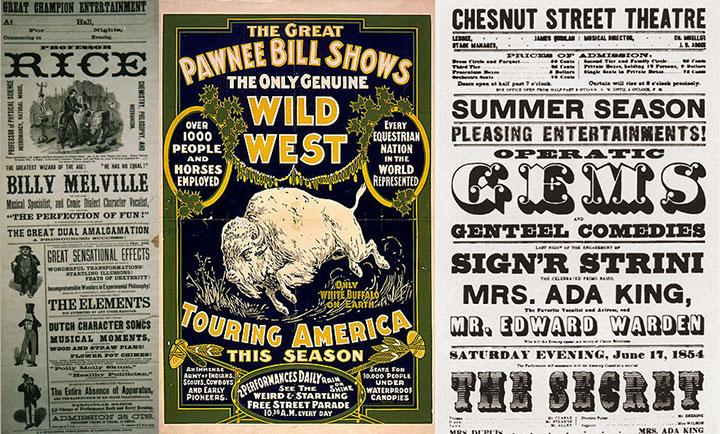

Hand-in-hand with letterpress printing, the art of the broadside has also survived and evolved into a modern format. The term broadside means any single sheet used to convey information, often of a political kind—the great-grandpappy of the modern poster. While today the words broadside and poster are sometimes used interchangeably, the broadside has remained a favorite of the letterpress community because of its emphasis on typography and content (hey, we need an excuse to use all that gorgeous metal type!).

Jessica and I had this history in mind when we began the Dead Feminists series. As I said before, we never dreamed of starting down the path we’re on now; we just wanted to make a political and artistic contribution to the election. And to pay homage to the history of the broadside and the era in which each of our feminists lived, I designed each piece with historic broadsides and posters in mind. And to keep the series consistent, Jessica and I came up with a few rules of engagement:

1. Each poster has to feature a quote by a feminist. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a woman, but there are already plenty of posters highlighting the words of dudes, so we figured that one was covered already.

2. Said feminist must be deceased. (Hence the name.) You’d be surprised how many challenges that’s created for us.

3. Each quote is tied into a current sociopolitical issue or event. This is usually Jessica’s job, as she’s got a particular knack for finding relevant quotes.

4. The whole piece (except the colophon at the bottom, of course) is hand-drawn.

5. We try to stay away from well-worn tropes like “women can do anything men can do!” in favor of broader topics and concepts.

Who knows how long people will be interested in these things, or how many broadsides there’ll be in the series—all we can say is that we’re grateful for the response people have had, and we’re having way too much fun to quit now. The fun of art-making and the joy of the public response aside, the best part of creating this series has been exploring the lives and work of so many inspirational people. “Feminism” has become somewhat of a dirty word these days—mostly because of misconceptions. To us it’s a positive thing, and creating this series is our way of celebrating those who championed far more than just gender equality. Besides, we’d like to make our own contribution to our social history—and using the “power of the press” in the literal sense is the best way we know how.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Coming in part two: the nitty gritty details behind our process.

May 12th, 2009

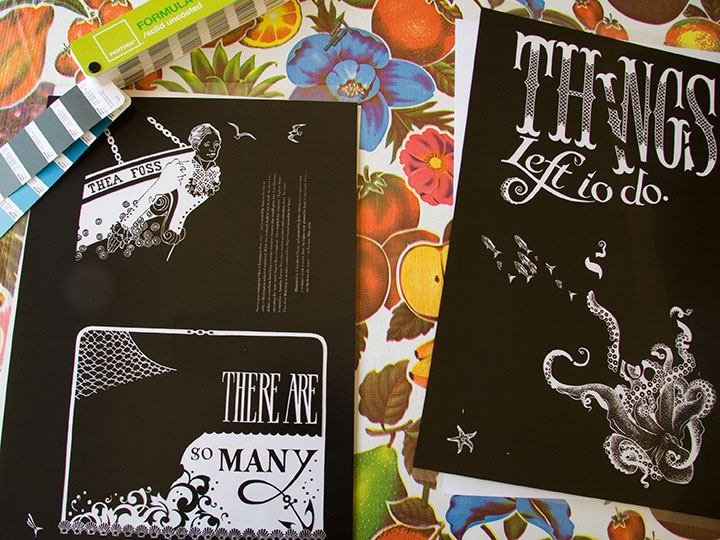

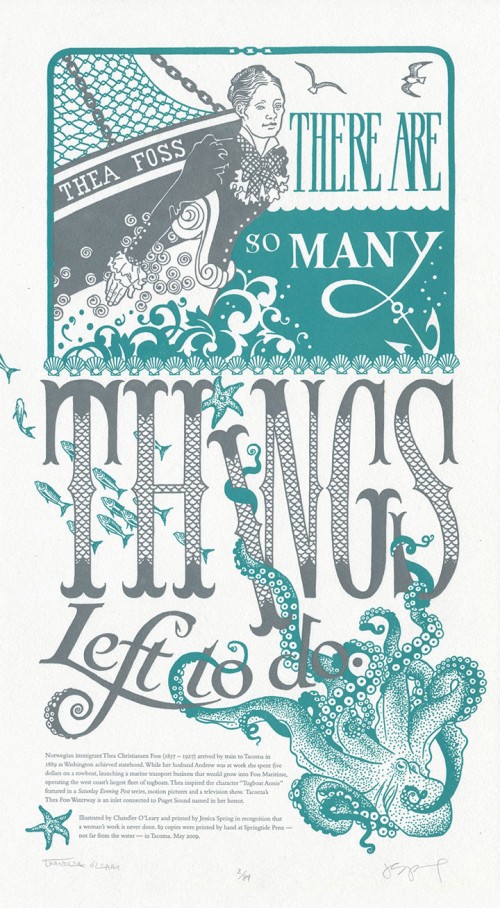

Well, here she be. (Or should I say, Thar she blows?)

At long last, Thea is here, barnacles and all. Jessica and I unveiled her at our Pressing Matters talk at the Tacoma Art Museum this morning. I have to say, I was nervous that with the weekday morning time slot, we’d be hoist on our own petard for the big debut. Since 10:30 on a Tuesday isn’t exactly an hour available to everybody, we were afraid we’d be lecturing a bunch of empty chairs. Boy were we wrong. Many thanks to all of you who skipped out on work, took a long (and very early) lunch, or otherwise carved out an hour of your day to spend with us—we raise our pirate flags to you. And to Allison Baer, TAM’s very own renaissance woman who made it all happen, you get the biggest Jolly Roger of them all. Thank you.

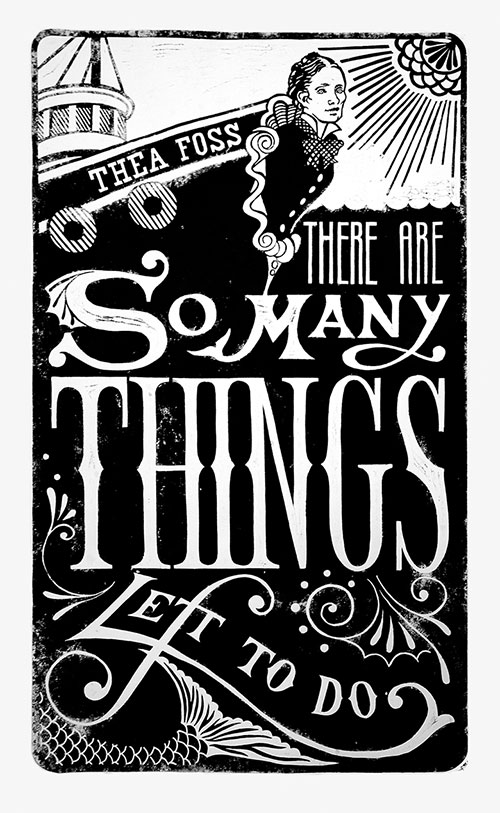

This week I’m going to post some of the things we talked about today at TAM, about the making of Tugboat Thea and our series. But for now, let’s just get down to brass tacks about the broadside. Here’s the quote that started it all:

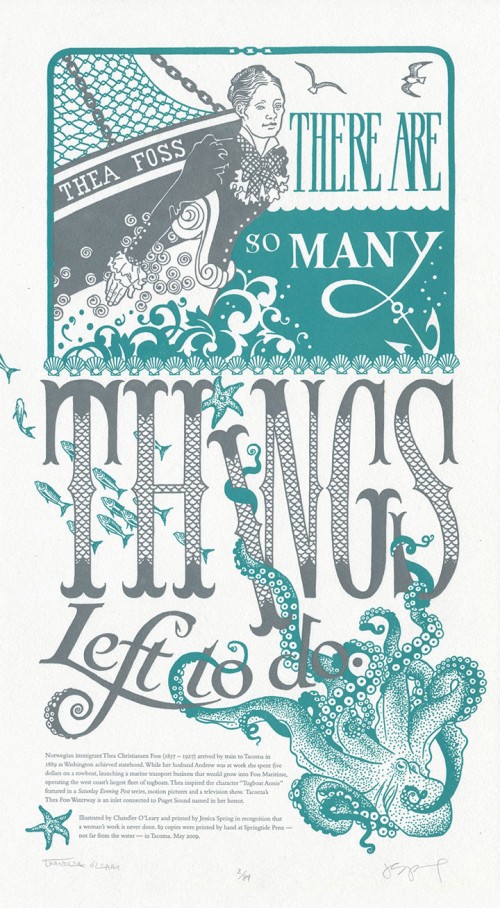

There are so many things left to do. — Thea Foss

In honor of enterprising women everywhere, the print features business pioneer and entrepreneur Thea Foss, who founded the Foss Tugboat company in Tacoma, WA—at a time in history when it was not only courageous, but nearly unheard of for a woman to do so. Here Thea is portrayed as the figurehead of her own tugboat, surrounded by crashing waves and sea life native to her home waters of Puget Sound.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Tugboat Thea: No. 4 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 89

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Norwegian immigrant Thea Christiansen Foss (1857 – 1927) arrived by train to Tacoma in 1889 as Washington achieved statehood. While her husband Andrew was at work she spent five dollars on a rowboat, launching a marine transport business that would grow into Foss Maritime, operating the west coast’s largest fleet of tugboats. Thea inspired the character “Tugboat Annie” featured in a Saturday Evening Post series, motion pictures and a television show. Tacoma’s Thea Foss Waterway is an inlet connected to Puget Sound named in her honor.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

May 7th, 2009

Thea’s back! This is just a sneak peek of the pencil sketch for now; Jessica and I are unveiling Ms. Foss’s new look on Tuesday, so we’re saving the surprise for then. In the meantime, though, we thought we’d offer up a few snippets.

The latest broadside in our Dead Feminists series has been a little bit of a different process, at least on my end. We had the chance to create a prototype of sorts when we were asked to make steamroller prints at the Wayzgoose this year. But while several hundred people were there to witness the steamroller in action, only eight huge Tugboat Thea prints exist—not exactly ideal in the supply-and-demand sense. By redesigning the piece, we we’d no longer be limited by what we could hand-carve out of a slab of linoleum. So we let the first Thea serve as a rough draft, and took another crack at it for the official series.

This time, though, there’s a bit of a twist. That’s all I’ll say for now.

As part of the unveiling of the new Tugboat Thea, Jessica and I will be speaking at TAM on Tuesday morning. If you’re in the area, and you can fit the weird time slot into your schedule (sorry about that), here are the details:

Pressing Matters:

Contemporary Collaborations Highlighting Women in History

Tuesday, May 12, 10:30 a.m.

Tacoma Art Museum, 1701 Pacific Ave.

Tugboat Thea will be available for sale at the event, too—look for it to appear here afterward!

April 7th, 2009

Since my gallery talk on Sunday was limited to a local audience, I thought I’d highlight a few of the pieces in my To the Letter show. (Besides, in a blog post I don’t have to worry about any public-speaking nerves, or hear myself say “Uh” or “um” twenty-nine times a minute.)

The only wall piece in the exhibit is Tugboat Thea, a piece I did with Jessica. The print is an unofficial member of our Dead Feminists series because of its size, and let me tell you, that sucker is huge. (Four feet tall!)

And why is it so enormous? Why, it was printed with a steamroller, of course!

Yes, you read that right. The folks at King’s Books asked us to be a part of their fifth annual Wayzgoose* celebration on the first of March, and steamroller printing was the main event. Thanks to a grant from the Tacoma Arts Commission (seriously, thank you!), each artist or artist-team was given a four-foot slab of linoleum to carve as they saw fit. Jessica and I decided to pay tribute to Tacoma’s own Thea Foss—business pioneer, Waterway namesake, feminist extraordinaire, and inspiration for the Tugboat Annie stories and films.

The trouble was, our Feminist Broadside format relies on a quote by the subject, and we were having an awful time finding anything attributed to Thea herself. Luckily we discovered Finding Thea, the excellent documentary film by Nancy Bourne Haley and Lucy Ostrander—which, by the way, also provided great reference material for sketches.

This should give a rough idea of the scale we were working with. To transfer our image onto the linoleum (backwards, so it’ll print correctly), we photocopied my design drawing at 600% size, placed the copy face-down onto the linoleum, sprinkled it with mineral spirits, and ran a hot iron over the wet paper. The heated solvent transferred the copy toner onto the linoleum exactly the way we wanted it. Then we just had to spend a week carving it!

Here’s the finished block, all inked up and ready to print.

And here’s the print, hot off the press. Nancy, the director of the documentary, even jumped in to help!

Despite weather that absolutely refused to cooperate and ink turned soupy by the rain, the Wayzgoose was a huge success. We had over 500 people in attendance, and every steamroller artist knocked out at least a few prints.

Since the prints are so unwieldy, and since we can only print a handful of them at an event like Wayzgoose, we’ve decided to retool the design of Tugboat Thea. We’ll print a (smaller!) letterpress edition as the next in the Dead Feminists series. Look for it here soon!

I have to say, though, I’m grateful we were able to find a genuine Thea quote—it was either that or this nugget from the old Tugboat Annie stories:

“O.K., ye ol’ gafoozler,” she replied quietly and stood up.

Alright, I admit it: anything using the word “gafoozler” is going to be a major temptation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

* Wayzgoose (origin obscure): a celebration given by a master printer to his workmen each year to mark the traditional end of summer and usher in the season of working by candlelight. Generally held as an annual celebration of letterpress and the book arts today.

April 4th, 2009

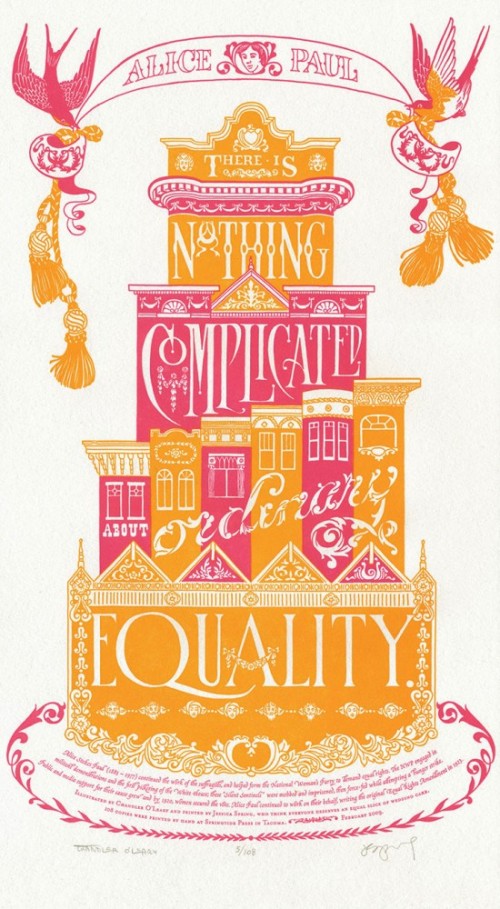

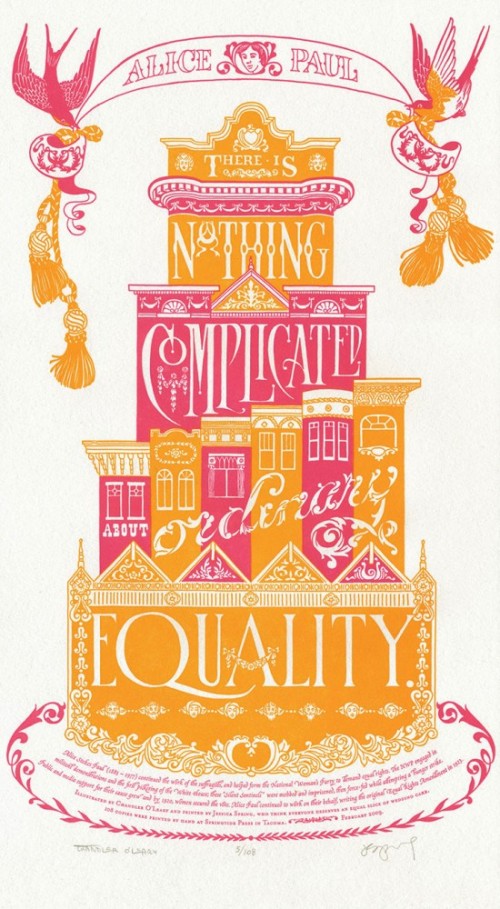

Jessica Spring and I have been having a high ol’ time with our Dead Feminists series thus far, celebrating positive changes happening around the country with the first two prints we created. At the same time, we were shocked and dismayed to learn that Proposition 8 had passed in California. Now, I know that people are extremely divided on this issue, so in the interest of respecting others I’ll try not to open any worm-cans here (this is an art blog, not a soap box). But we wanted to express our thoughts on the matter, so Prop Cake was born. The quote we chose made the issue seem like…well, a piece of cake:

There is nothing complicated about ordinary equality. —Alice Paul

The initial idea for this piece came almost immediately; Jessica looked over at me on a drive home from Seattle one day and said, “How about a big, pink wedding cake?” I grinned from ear to ear, and started sketching as soon as I got home. The design didn’t come together so easily, however. Everything I came up with looked more like an ad for Modern Bride than a political poster. Frustrated, I pushed my sketches aside and took a few days off to think.

And then I went to San Francisco.

It was my first trip there, and my first thought as I passed through the residential neighborhoods, with rows and rows of candy-colored stucco houses, was “Wow, these things look like big frosted cakes!” And the lightbulb turned on, at last. I spent three days walking, driving, and riding around the neighborhoods, camera and sketchbook in hand. I made pages and pages of notes on architectural detailing.

When I arrived home, I got right to work. This time, finally, it all came together.

Alice was right—it really was a piece of cake.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Prop Cake: No. 3 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 108

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Alice Stokes Paul (1885 – 1977) continued the work of the suffragists, and helped form the National Woman’s Party to demand equal rights. The NWP engaged in militant demonstrations and the first picketing of the White House; these “Silent Sentinels” were mobbed and imprisoned, then force-fed while attempting a hunger strike. Public and media support for their cause grew and by 1920, women secured the vote. Alice Paul continued to work on their behalf, writing the original Equal Rights Amendment in 1923.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

April 3rd, 2009

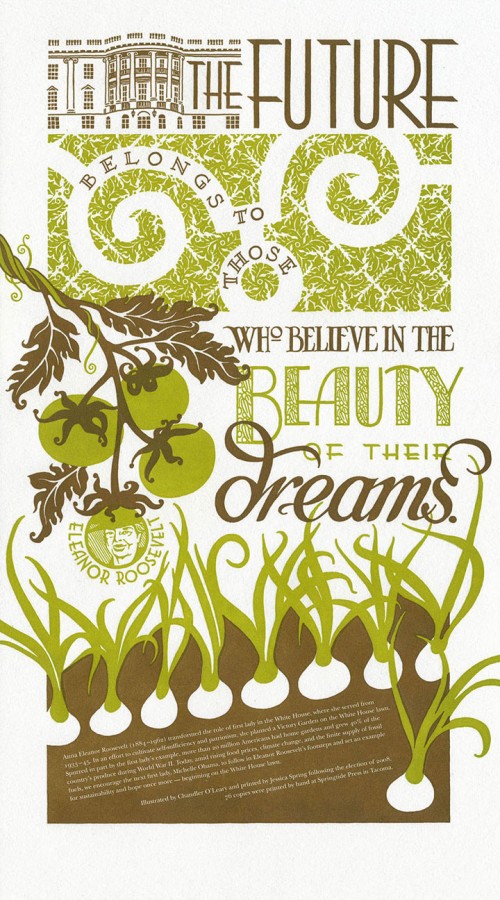

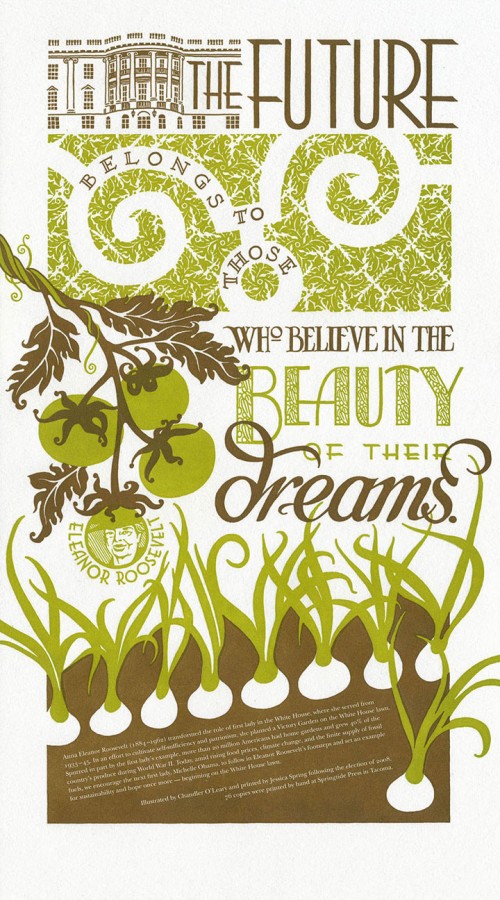

With the success of our first piece, Jessica and I wanted to continue our Dead Feminists series with something that upped the ante a bit. And to our complete shock, we were rewarded by our second broadside selling out in just 48 hours (thanks to the magic of the internets!). Our next subject was one that we both had been thinking about for some time: personal sustainability. As the Tailor and I are both hard-core seasonal foodies (more on this topic will probably come out eventually), and as Jessica is a member of a local crop share, we’d like to see a change in the American food system. So we turned to one of our favorite feminists: Eleanor Roosevelt.

The future belongs to those who believe in the beauty of their dreams.

While serving as First Lady, Roosevelt planted a White House victory garden during World War II; thanks to her inspiration and example, during the War home gardens accounted for 40% of the U.S. supply of vegetable produce. We thought, hey, if it could be done once, why not again? So the colophon at the bottom included a plea for the new First Lady, Michelle Obama, to carry on in Roosevelt’s footsteps.

My inspiration for the design of Victory Garden came from a variety of sources. For one thing, the typography is inspired by the Art Deco designs of Roosevelt’s era. For another, I thought back to my honeymoon in France last year.

I spent a day at Versailles on that trip, and at the time was struck by the meticulous aesthetic that unified every element of the place. Everything from the wallpaper to the upholstery to the grounds themselves worked together to form a cohesive overall design. An overly ornate and despicably ostentatious design, sure (and a bit ironic, considering Marie Antoinette’s consequences for going overboard with luxury in the face of a starving populace), but it was beautiful in its own right. I especially loved the sculpted hedges and lawns of the Versailles gardens; the patterns form a stunning, living brocade at one’s feet. And I wanted to turn that design sense into something that represented the greater good, rather than the wealth of the few. So I abstracted that idea into a two-dimensional White House lawn, made up with an original brocade pattern of spiraling leaves.

When we finally arrived at the finished product, we were happily surprised to learn that many others had had similar thoughts. We discovered Michael Pollan’s editorials; learned about the “Eat the View” movement; and found many other like-minded folk along the way—including one who purchased a copy of Victory Garden for her friend, a direct descendant of Eleanor Roosevelt herself. As the icing on the cake, one of our Chicago customers had a personal connection to the Obamas, and promised to deliver a copy of the broadside to the First Lady, with our compliments. We have no idea if it actually reached her in the end, but there’s always hope. And besides, we’re taking a bit of personal pride in being part of a larger movement, as well as the fact that the new White House garden is already happening.

Victory garden, indeed.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Victory Garden: No. 2 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 76

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (1884 – 1962) transformed the role of first lady in the White House, where she served from 1933-1945. In an effort to cultivate self-sufficiency and patriotism, she planted a Victory Garden on the White House lawn. Spurred in part by the first lady’s example, more than 20 million Americans had home gardens and grew 40% of the country’s produce during World War II. Today, amid rising food prices, climate change, and the finite supply of fossil fuels, we encourage the next first lady, Michelle Obama, to follow in Eleanor Roosevelt’s footsteps and set an example for sustainability and hope once more—beginning on the White House lawn.

Poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

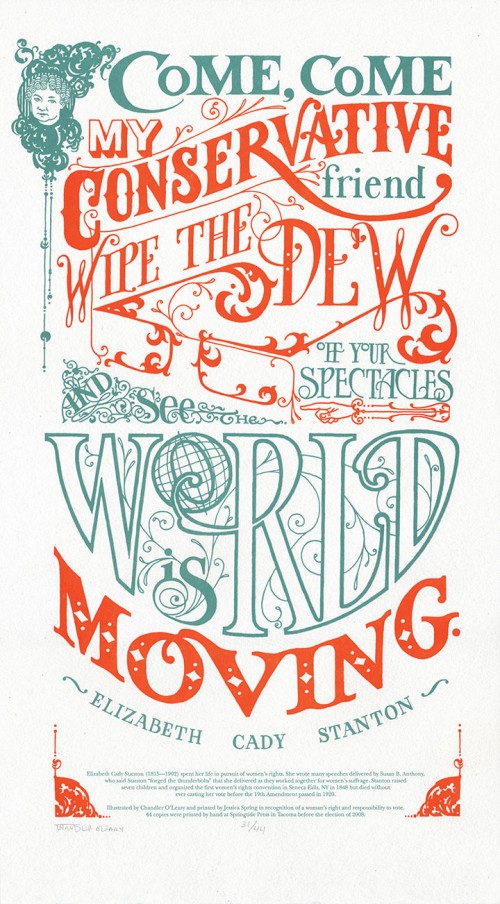

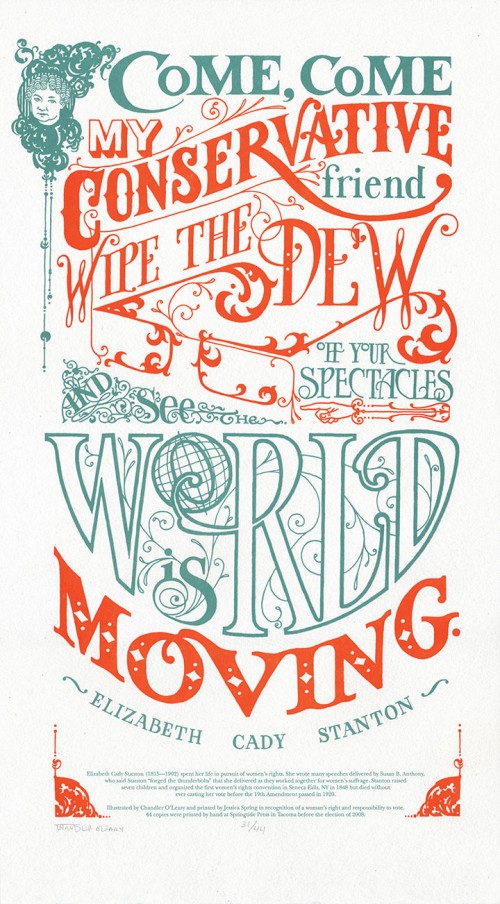

April 2nd, 2009

This blog might be brand new, but I should probably bring you up to speed on a project that isn’t. Starting last fall, right before the 2008 Presidential Election, my friend and fellow letterpress printer Jessica Spring asked me if I wanted to collaborate on a political broadside (basically, a letterpress version of a poster) together. We both felt like this was an important event, and a moment in history, and we wanted to make some sort of contribution to the artistic record. Jessica said she had a historical quote that would be fun to typeset, and asked if I could do a quick illustration of a pair of spectacles to go with it. She thought it’d be fun to make the glasses look like the famous eyewear of a certain Alaskan VP candidate (who can see Russia from her house!)—her plan was to use her impressive collection of wood and metal type to hand-set the quote into the design.

Well, she probably shouldn’t have left me alone with my pencils, because I got a little carried away, and drew not just the glasses, but the whole quote around them, too:

Come, come my conservative friend, wipe the dew off your spectacles and see the world is moving. — Elizabeth Cady Stanton

I did this because I wanted the piece to be something more than simply a jab at a political personality. I wanted it to be beautiful in its own right, something that might do justice to Stanton’s words, and that would be longer-lasting than a momentary visual pun. Besides, Stanton put up one of the most important fights in American history: women’s suffrage. In this country with with a voter turnout rate of less than two-thirds, I wanted to do my small part to get women everywhere, regardless of political stripe, to the polls. And then, as it always does, my fingers started itching to draw my own letterforms. After all, for as much as I love hand-setting type, one of the reasons I’m a letterer is because I’m continually frustrated by the finite number of typefaces available in wood and metal. Not that I’m happy with choosing among the thousands and thousands of digital font families out there, either. Let’s just say I’m picky. So I made up my mind to letter the whole thing by hand, and not to tell Jessica until the sketch was done.

Bless her heart, she went along with the idea. We scrapped the idea of setting vintage type and printed the image using a modern material called photopolymer plates (more on that another day). And then we put the broadside into our online shop, and sent out an email to our little mailing list to let them know we’d made something new.

Three days later, the entire edition of prints was sold out. We were floored! Neither of us had ever experienced this kind of clamoring for our work before—we’d both sold out editions before, but not this quickly. People started emailing us and asking if we were going to do more posters. After reading that, we kind of looked at each other and said, “Why not?”

And the Dead Feminists series was born.

(More on the series another day: first, let’s get to the details about the broadside itself:)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Come, Come: No. 1 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 44 prints

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815 – 1902) spent her life in pursuit of women’s rights. She wrote many speeches delivered by Susan B. Anthony, who said Stanton “forged the thunderbolts” that she delivered as they worked together for women’s suffrage. Stanton raised seven children and organized the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY in 1848 but died without ever casting her vote before the 19th Amendment passed in 1920.

Poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)