Blog

February 13th, 2010

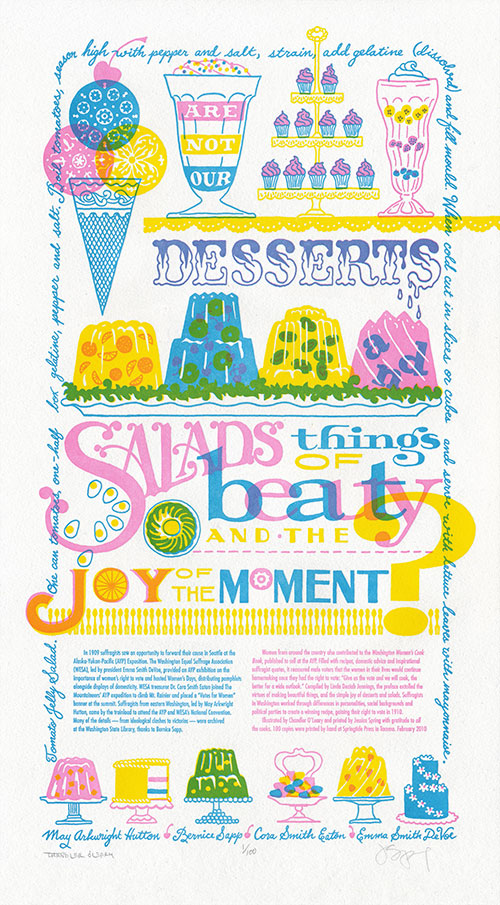

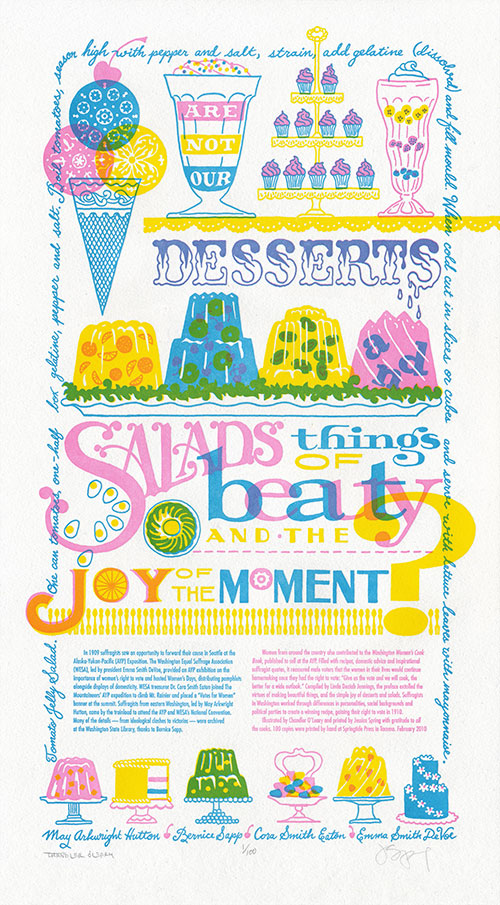

This year marks the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in Washington—a feat only made possible by the collaborative efforts of many dedicated people of every walk of life and political stripe. In this spirit, we present our seventh broadside in the Dead Feminists series, Just Desserts.

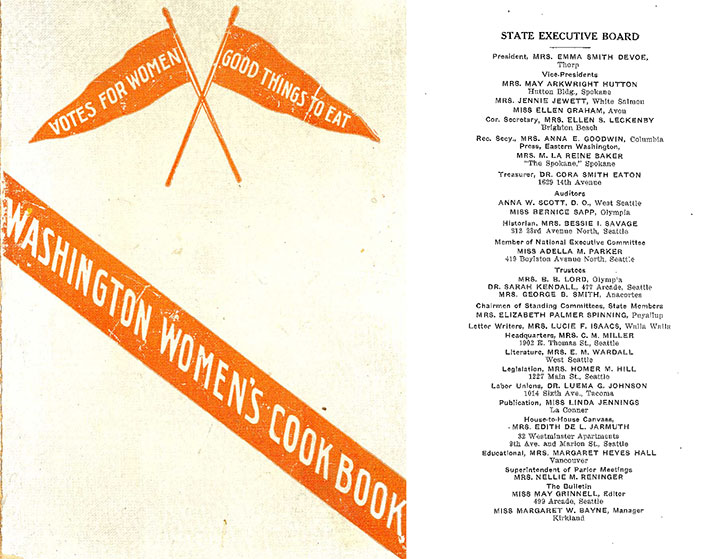

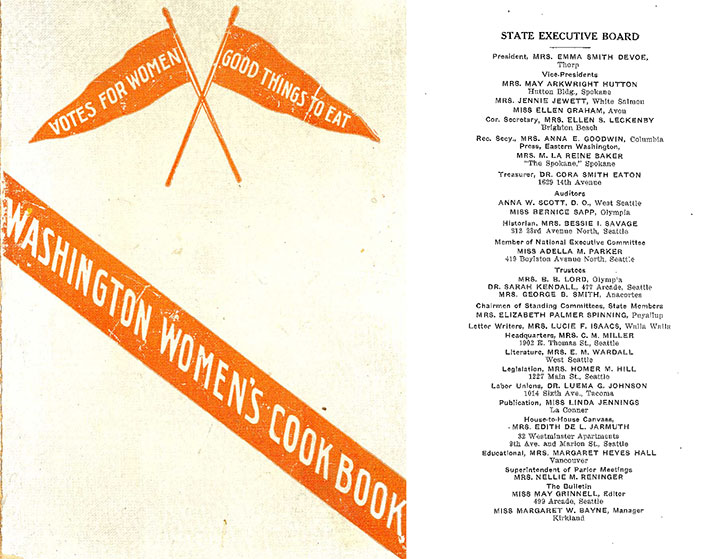

Through our research at the Washington State Library, we discovered that our state’s suffrage movement had many leaders, rather than one prominent figurehead. We also learned that there was so much head-butting, personality-clashing and partisan in-fighting going on within the organizations involved (Mesdames Hutton and DeVoe, I’m looking at you!) that it would be impossible to tell the whole story in one letterpress poster. So instead of quoting a single historical feminist, we cited a collaborative publication—the Washington Women’s Cook Book, published in 1908-1909 for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition—and featured four women symbolic of the movement: May Arkwright Hutton, Bernice Sapp, Cora Smith Eaton, and Emma Smith DeVoe. The quote:

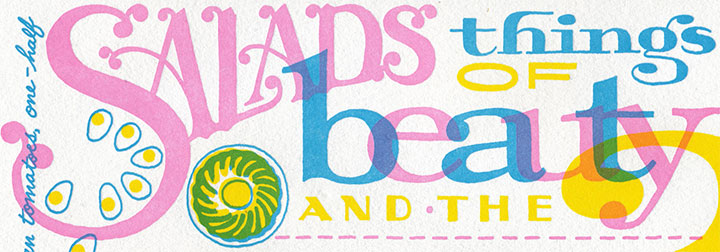

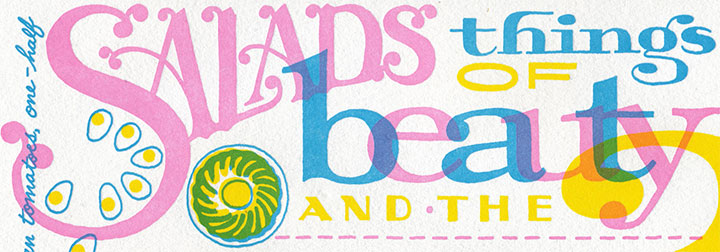

“Are not our desserts and salads things of beauty and the joy of the moment?”

The book was a clever piece of propaganda that operated on the principle that the way to a man’s heart—or vote—is through his stomach. All those jellied centerpieces and whimsical soufflés must have done the trick—the following year, women got the vote.

And for my part, the quote turned me into an almost-literal kid in a candy store; the design was just begging for elaborate confections and candy-coated typography. At first, though, I was turned off by the idea of having to draw salads (I wanted more ice cream!), until Jessica read off a litany of aspic salad and gelatin dessert recipes from the book. That’s when the light bulb turned on: Jell-o salad! The decade-plus I spent in the Midwest was about to serve me well.

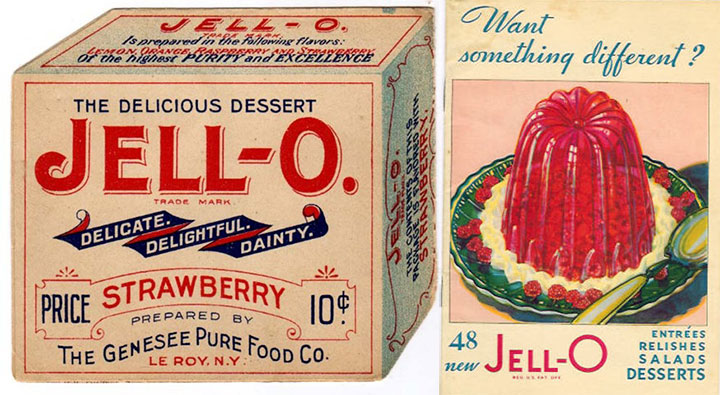

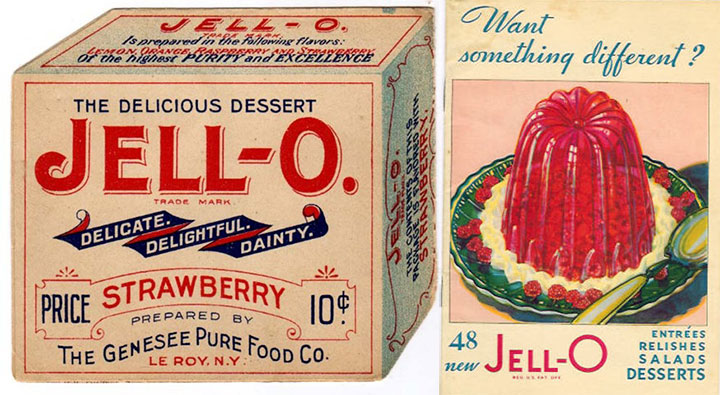

Turns out that Jell-o fit right into the turn-of-the-century theme: molded gelatin desserts were a Victorian favorite, and the name “Jell-o” was first coined in 1897 (and if you look carefully, the “J” from the original Jell-o box makes a cameo in the print). There seemed to be no end of antique recipes, advertisements and illustrations at my disposal.

I might be horrified by the idea of eating gelatin salads, but drawing them was the most fun I’ve had in a long, long time. Zooey and I each spent hours researching vintage Jell-o molds—probably more for the pure fascination than for the value of the reference material.

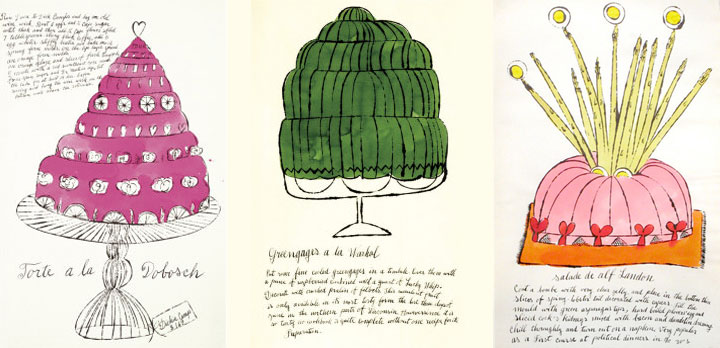

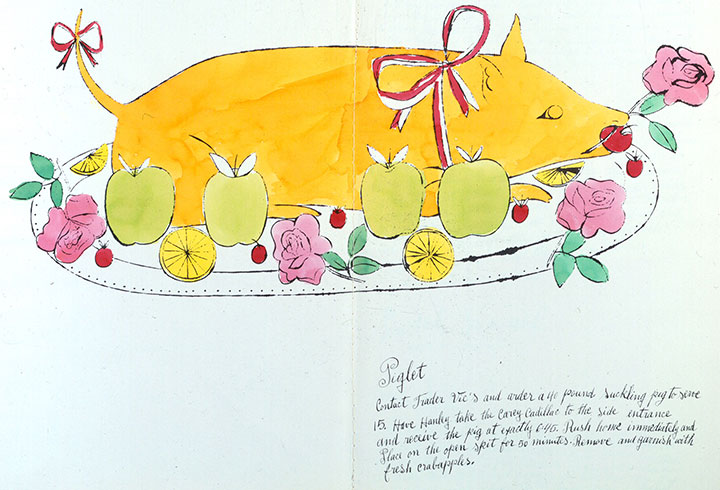

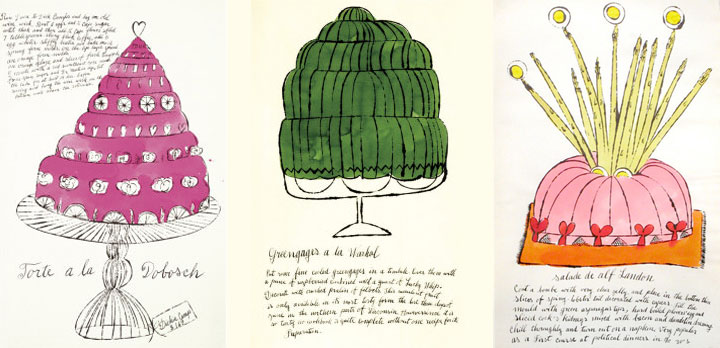

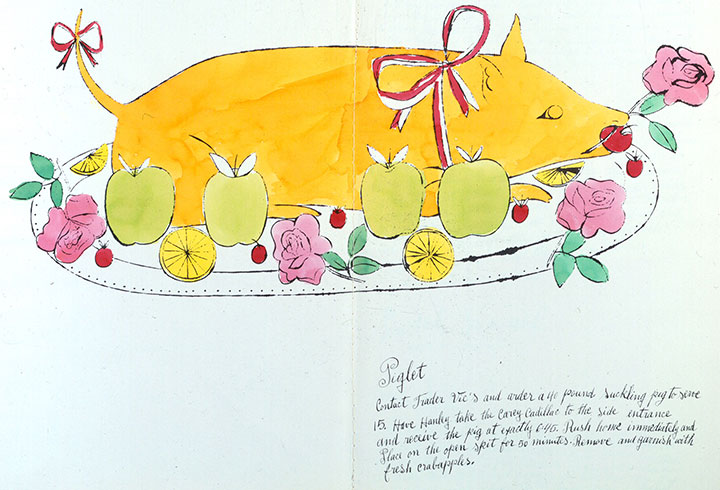

For the sweets portion of our little menu, I turned to an old favorite for inspiration: Andy Warhol.

Forget what you know about Campbell’s soup cans or Elvis portraits; Andy got his start as an illustrator specializing in fashion and food. In 1959 he illustrated a spoof cookbook called Wild Raspberries (it’s been on my shelf since high school, and I finally found a direct use for it!), filled with ridiculous “gourmet” recipes for things like “A&P Surprise” (those of you in New England will get that one) and “Seared Roebuck.”

The illustrations are fantastic (and the polar opposite of my style), but the thing that really drew me in was the lettering. Andy had his mother, Julia Warhola, write all of the text of his early illustrations in her shaky, school-girl script. Mrs. Warhola spoke little to no English, and simply copied her son’s notes letter-for-letter, so the text in Wild Raspberries has charming errors and misspellings throughout.

I loved the down-to-earth quality of Mrs. Warhola’s cursive, so I wrote a recipe from the Washington Women’s Cook Book along the border of the broadside in a similar hand (though to warn you, it’s a recipe I wouldn’t recommend trying!).

And of course, I couldn’t do without a little ice cream homage.

Like The Curie Cure, this piece is printed in three colors—although the three we chose let us create many more. Our color scheme allowed us to print in a similar fashion to commercial printing, where a minimum of colors (CMYK—cyan, magenta, yellow, black) are layered to create a full-color image. Our layering of translucent pink, blue and yellow ink allowed us to create a full rainbow and a convincing depiction of foreign objects floating in jelly.

Heaps of thanks to everyone who came to our talk at the State Library the other night, despite lousy weather and rush-hour traffic—we had a tremendous turnout, and a huge show of support for our state’s oldest cultural institution.

One more thing: three cheers for the incredible staff at the Washington State Library (many of whom are among those whose jobs have been cut and will end very soon) who made our talk and this very piece possible. Because we couldn’t have done it without them, we have donated a portion of our proceeds to support the State Library’s collections.

After all, it’s about preserving (in jelly?) that joy of the moment for everyone to share, right?

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Just Desserts: No. 7 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 100

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, each piece is printed on archival, 100% rag, recycled paper, and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

In 1909 suffragists saw an opportunity to forward their cause in Seattle at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (AYP) Exposition. The Washington Equal Suffrage Association (WESA), led by president Emma Smith DeVoe, provided an AYP exhibition on the importance of women’s right to vote and hosted Women’s Days, distributing pamphlets alongside displays of domesticity. WESA treasurer Dr. Cora Smith Eaton, joined The Mountaineers’ AYP expedition to climb Mt. Rainier and placed a “Votes for Women” banner at the summit. Suffragists from eastern Washington, led by May Arkwright Hutton, came by the trainload to attend the AYP and WESA’s National Convention. Many of the details—from ideological clashes to victories—were archived at the Washington State Library, thanks to Bernice Sapp.

Women from around the country also contributed to the Washington Women’s Cook Book, published to sell at the AYP. Filled with recipes, domestic advice and inspirational suffragist quotes, it reassured male voters that the women in their lives would continue homemaking once they had the right to vote: “Give us the vote and we will cook, the better for a wide outlook.” Compiled by Linda Deziah Jennings, the preface extolled the virtues of making beautiful things, and the simple joy of desserts and salads. Suffragists in Washington worked through differences in personalities, social backgrounds and political parties to create a winning recipe, gaining their right to vote in 1910.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring with gratitude to allthe cooks. 100 copies were printed by hand at Springtide Press in Tacoma. February 2010

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

January 30th, 2010

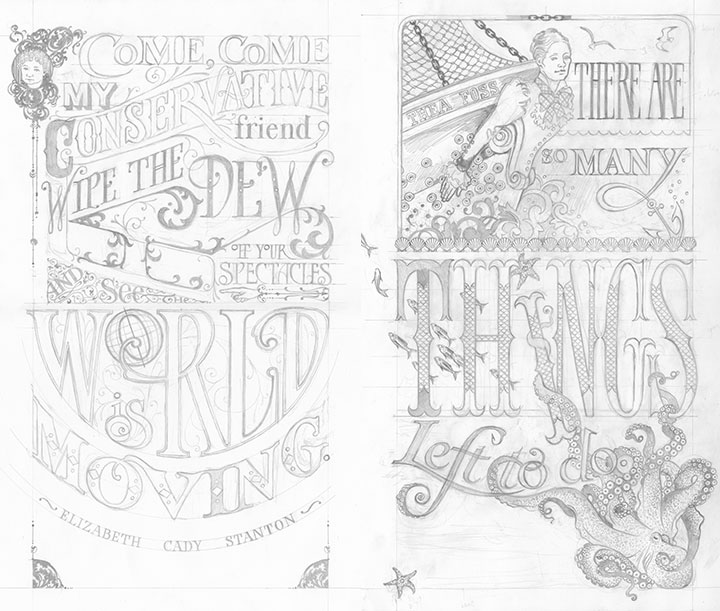

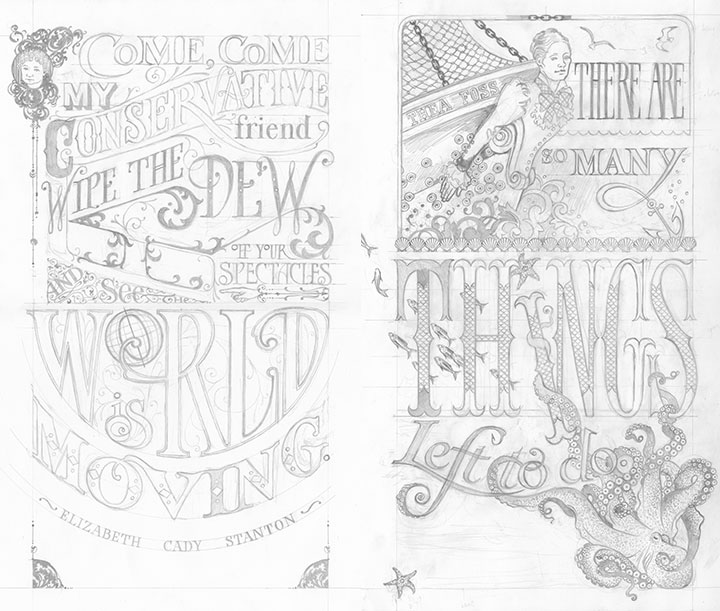

It’s just about that time again: Jessica and I are working hard on the next Dead Feminist broadside. She’s poring through texts and historical facts, and I’m pencilling as fast as my tendonitis will let me. This time we’ll be unveiling the new piece at the Washington State Library near Olympia; the staff invited us to give a lecture about the series next month.

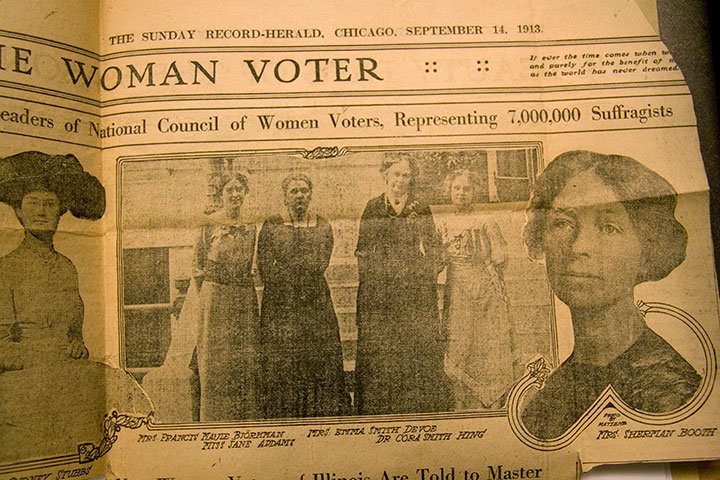

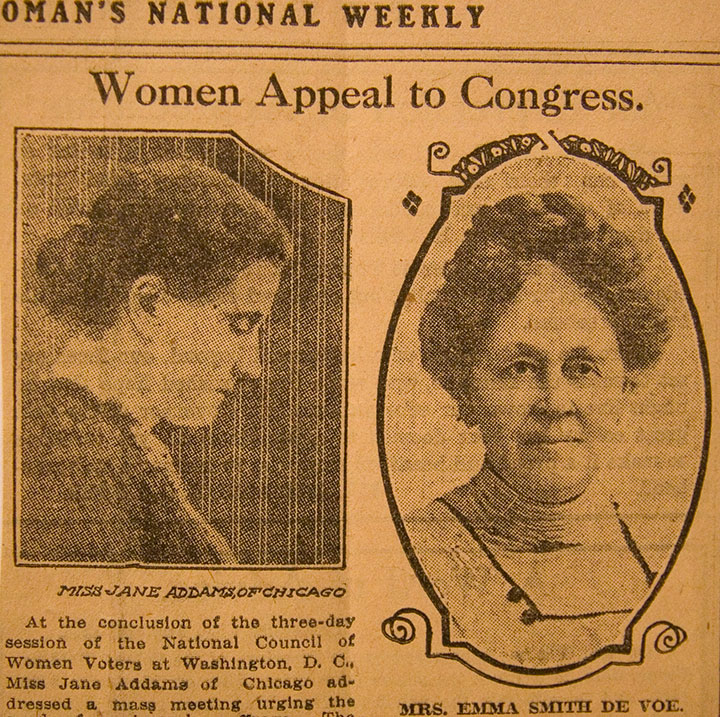

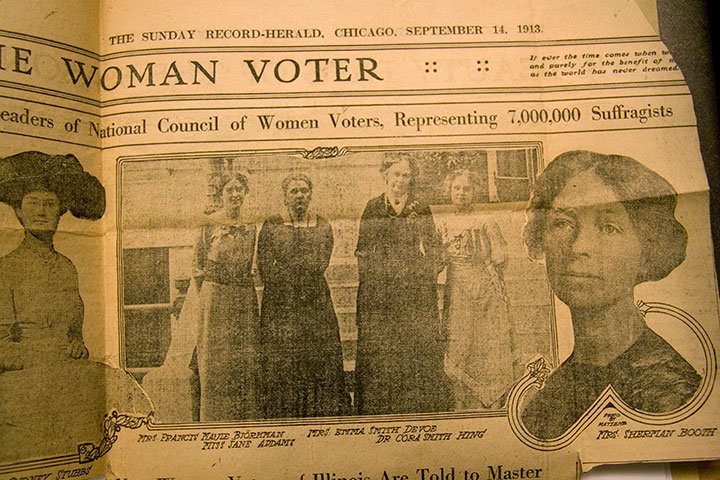

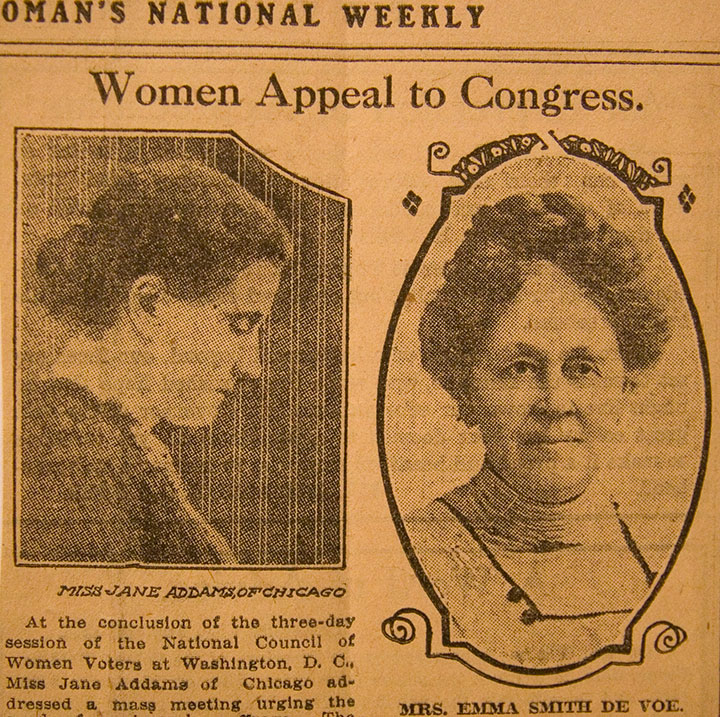

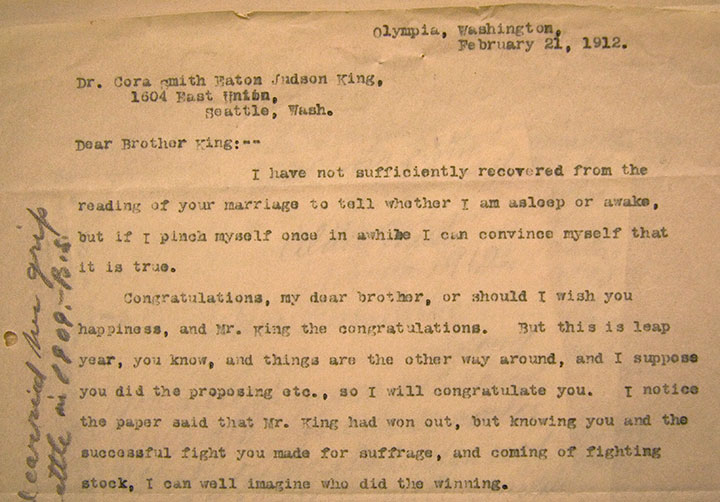

The library boasts the entire collection of letters and personal papers of Emma Smith DeVoe (pictured above, right), women’s rights activist and leader of the Washington suffragist movement. And since this year marks the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in Washington, we figured Emma would be a perfect fit for the new piece.

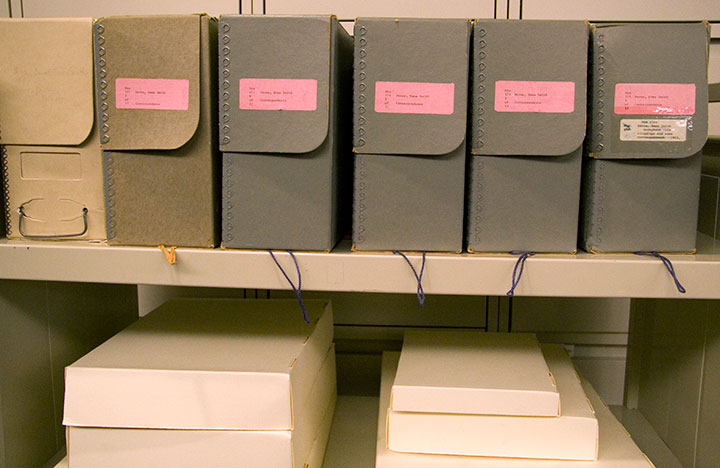

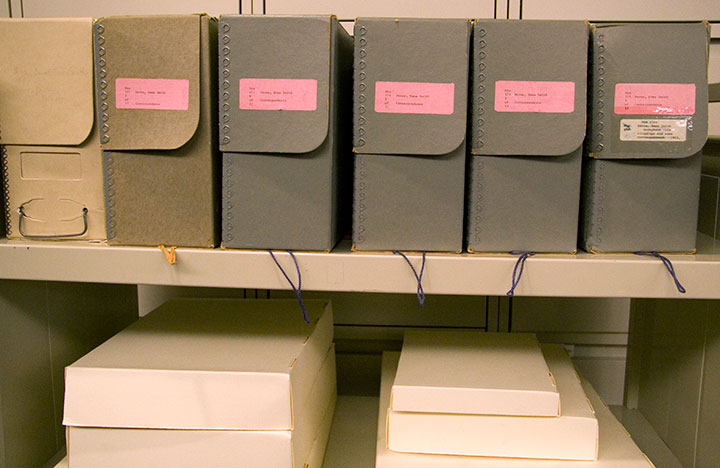

So a couple of weeks ago, Jessica, Zooey (R.I.P., J.D. Salinger) and I took a field trip to visit the archives and conduct a little research. When we arrived, we realized what they meant by “collection:” twelve enormous boxes packed full of letters, clippings and souvenirs. A “little” research obviously wasn’t going to happen.

Luckily, the incredibly knowledgeable and helpful library staff (thank you, Sean!) let us take as much time and as many photos as we needed. So we cozied up to a work station and dived in, one box at a time. Together we went through literally thousands of pieces of paper.

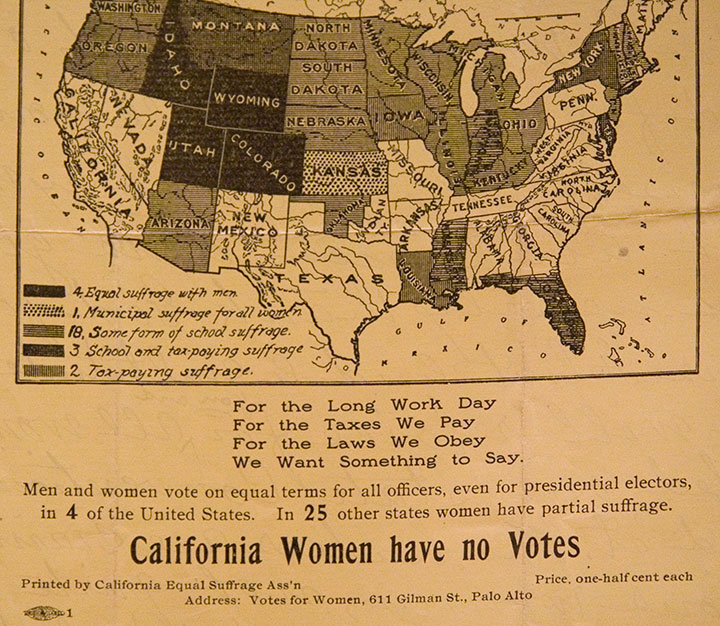

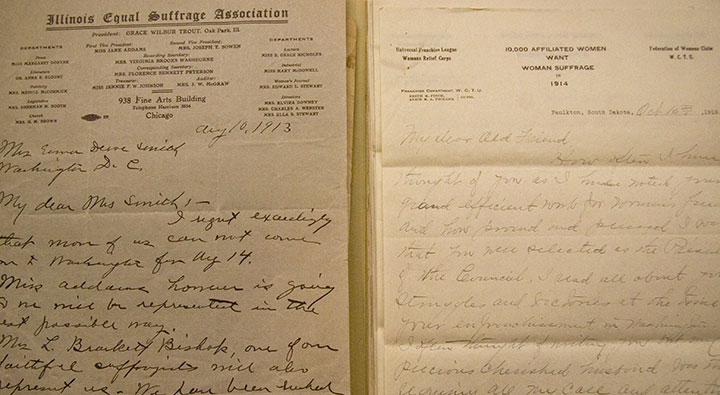

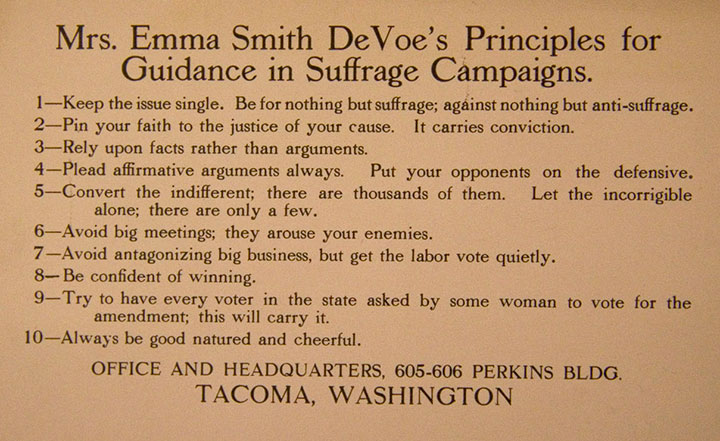

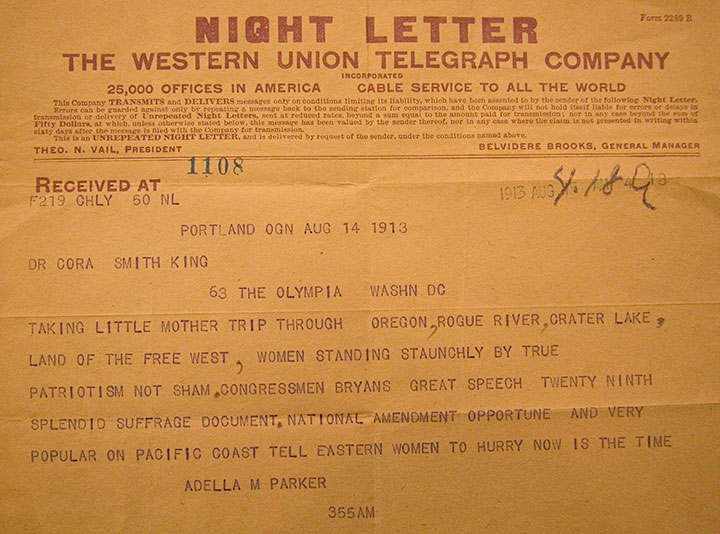

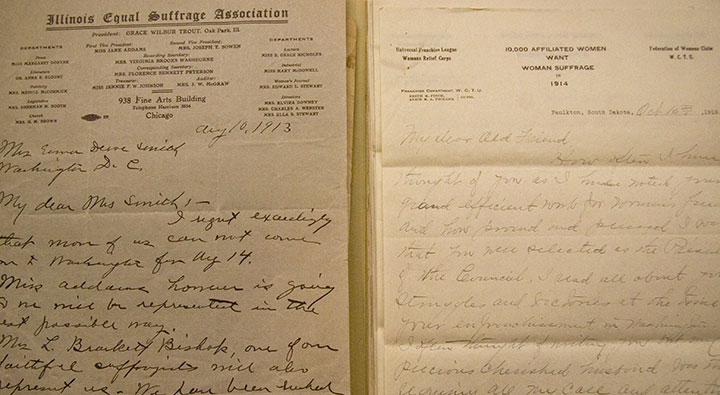

What we found was a fascinating collection of souvenirs, business cards, newspaper clippings,

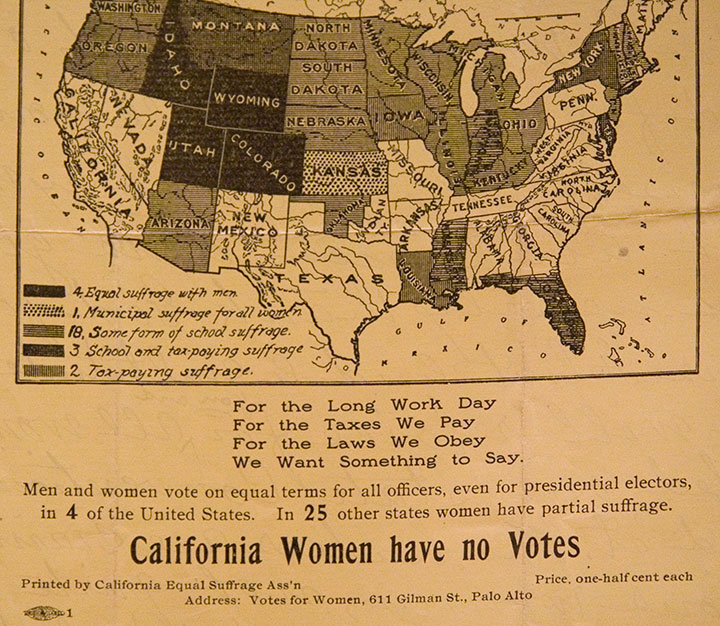

leaflets and other propaganda,

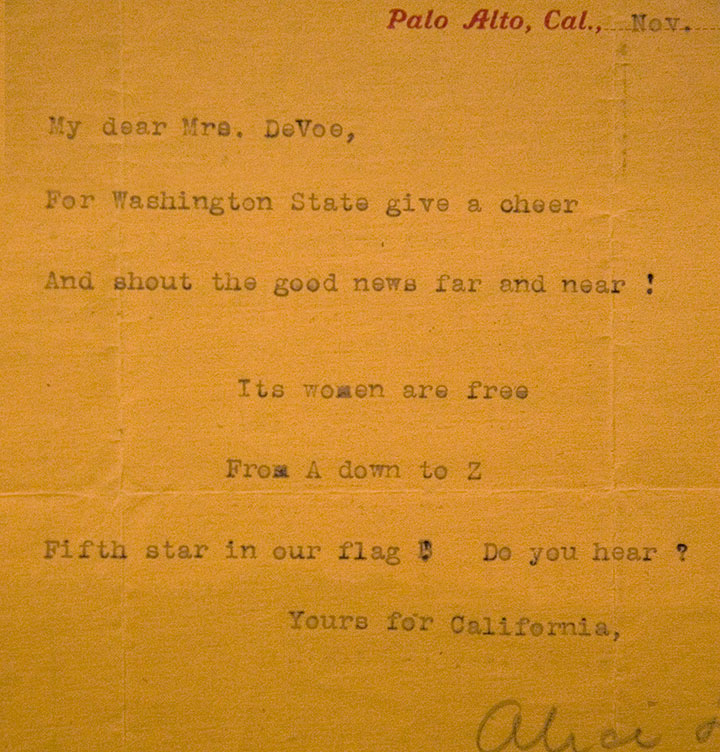

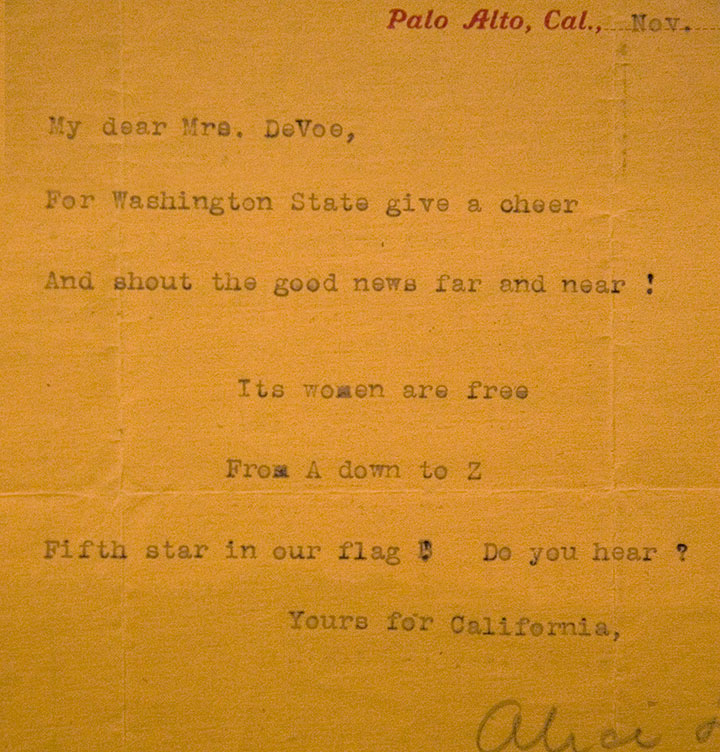

fan letters (Emma had an impressive array of admirers),

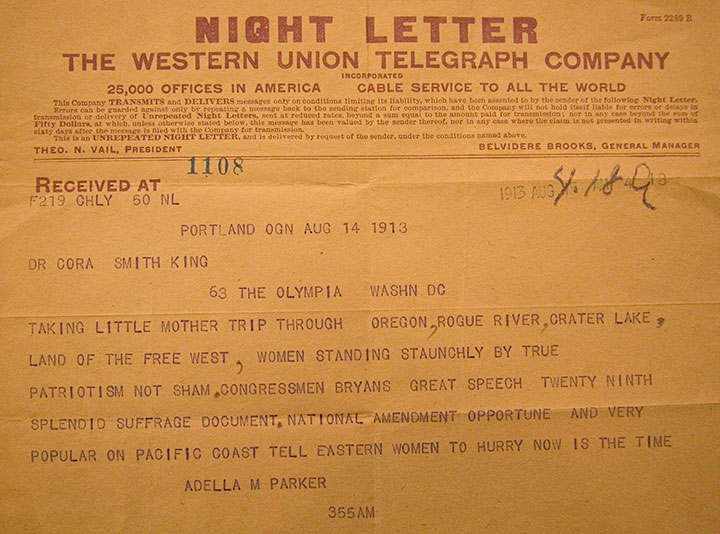

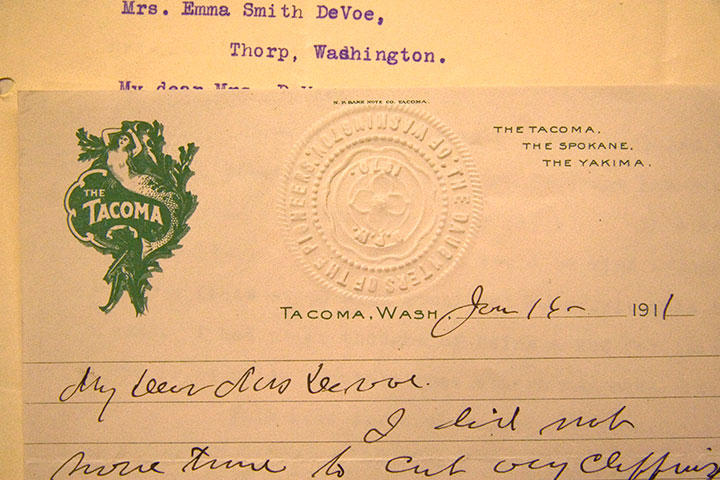

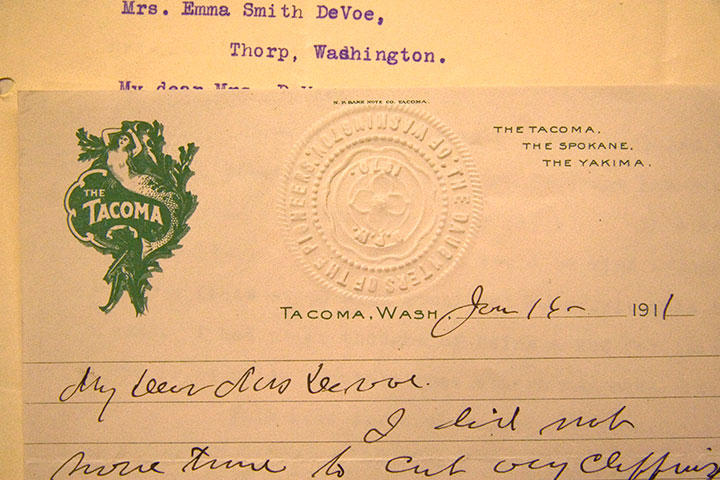

telegrams, notes from sitting U.S. senators and presidential aides, and reams and reams of correspondance between the members of the Washington suffragist movement.

The trouble was, most of these documents were utterly mundane—letter after letter simply acknowledged receipt of previous correspondance, or gave detailed instructions for planning events and delegating tasks. Worst of all, Emma rarely made carbon copies of her half of the correspondance, so there was very little in her own voice.

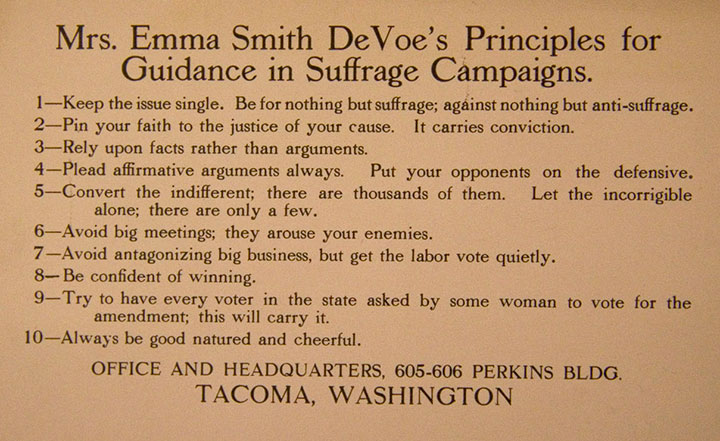

We spent nearly four hours poring over every folder and box, and the only potential Emma quotes we found were mined from this instructional card. Still, it didn’t feel like we had found our inspiration—just a few weeks from our talk, we had no quote and no social topic for the piece.

What we did have, however, was a much clearer picture of the women behind the fight for suffrage in our state (that’s May Arkwright Hutton above; she and Emma didn’t exactly get along), right down to addresses of homes and buildings still standing in Tacoma (the headquarters of the movement).

From the documents themselves to the individual script hands of each letter writer, we had an incredible window into political life from a hundred years ago.

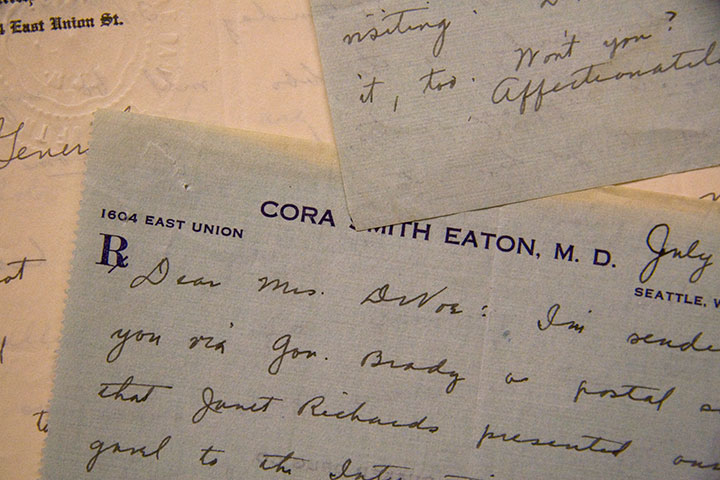

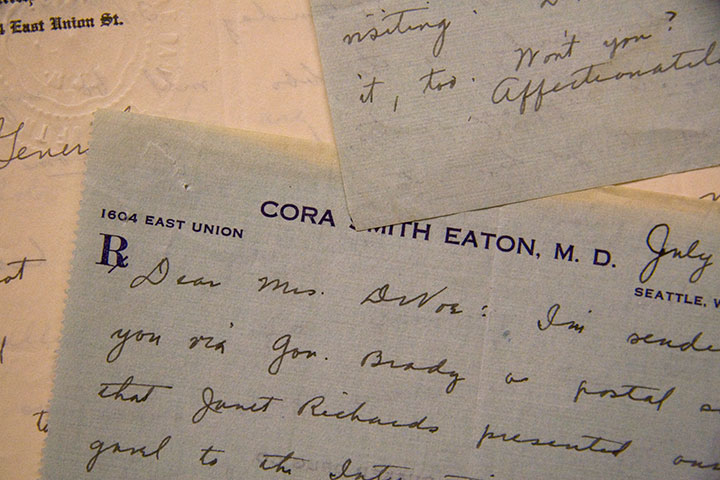

And we found a good lead. Just as interesting as Emma (and more forthcoming with their own voices) were Cora Smith Eaton King, M.D. (pictured above, right)—correspondent, fellow leader of the movement, and one of the first women to scale Mt. Rainier!—and Bernice Sapp—friend, activist, and the one who compiled this collection of documents and donated it to the library.

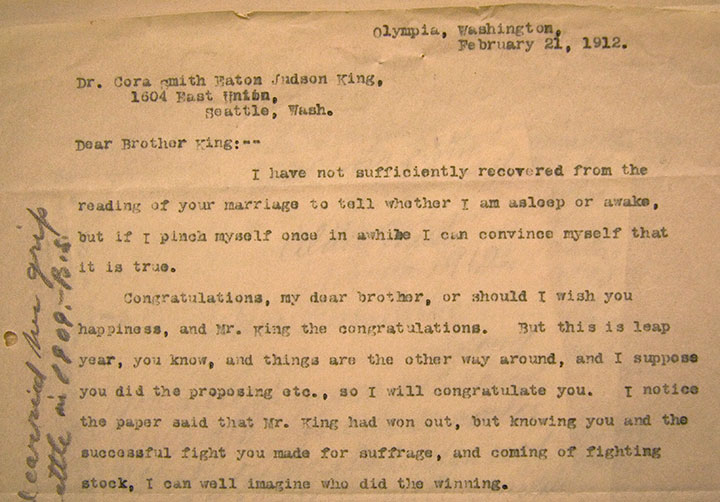

Bernice’s letters were full of quirky character and wit. We loved how she called Emma “the General,” and referred to herself and other suffragists by male titles: “Brother King,” “Mr. Hutton,” or simply “him.”

Cora, on the other hand, was a real firecracker. Her letters (often scribbled on scraps of paper, even her own prescription pad!) revealed an eloquent intelligence and a sizzling sense of humor. We fell head-over-heels for Cora, and began to doubt that Emma was the right voice for the broadside—still, though, we had no quote from any of these women.

A few days later, Jessica hit up the astounding Northwest Room at the Tacoma Public Library, and hit the jackpot. She discovered a document that linked all of these women together, which decided us on a slightly different approach to quoting historical feminists. That’s all I’ll say for now, except that the new broadside may or may not depict a certain quivering, questionable “food” substance:

If you want to be one of the first to see what the heck I’m talking about, I invite you to come check out our talk at the Washington State Library. Here are the details:

Pressing Matters: an evening with Chandler O’Leary and Jessica Spring

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

6:30 p.m. (doors open at 6:00), free!

Washington State Library

6880 Capitol Boulevard, Tumwater, WA

Libraries and archives face a tough reality in the current economy—especially here in Washington, where a regressive tax system has left the State Library with a 30% staff reduction and major cuts to its operating and acquisitions budgets. The 2003 earthquake damaged their building on the historic capital campus in Olympia, and forced them to relocate “temporarily” to a suburban office park a few miles south in Tumwater. Even when the economy recovers, it is unlikely the library’s funding will return to the levels it enjoyed in more prosperous eras, so the move to Tumwater is looking increasingly permanent. Despite these setbacks, the State Library continues to acquire new items (including our artwork!) for the collection and provide an essential service in preserving our state’s history. So please come and show your support for the library—a good turnout will help them provide more public events in the future, and might just go a long way toward saving them from another visit to the chopping block.

November 20th, 2009

People who stop by the house for the first time must really think I’m strange. Never mind our own personal farmers market residing in the attic and root cellar—these days the place looks like the the visual-art equivalent of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, with snips of paper, rows of identical bird portraits, bright watercolor cakes, brushes and pencils, boxes of envelopes, shipments waiting to go out, and stacks of prints covering every horizontal surface. It certainly gives new meaning to the term “cottage industry.” I guess that’s what happens when you decide to double your inventory right before the holidays.

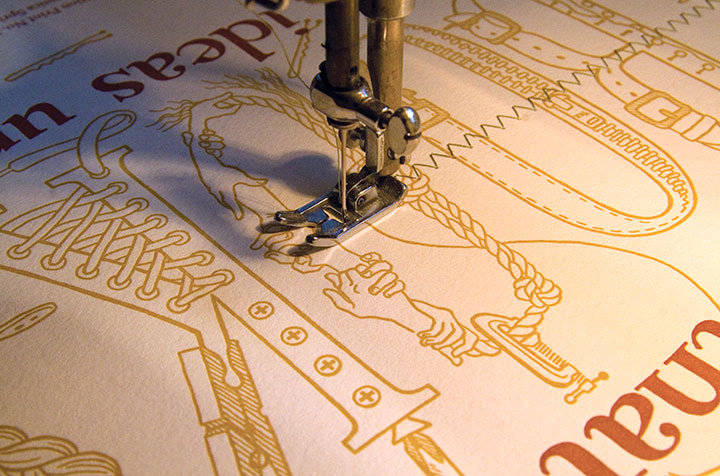

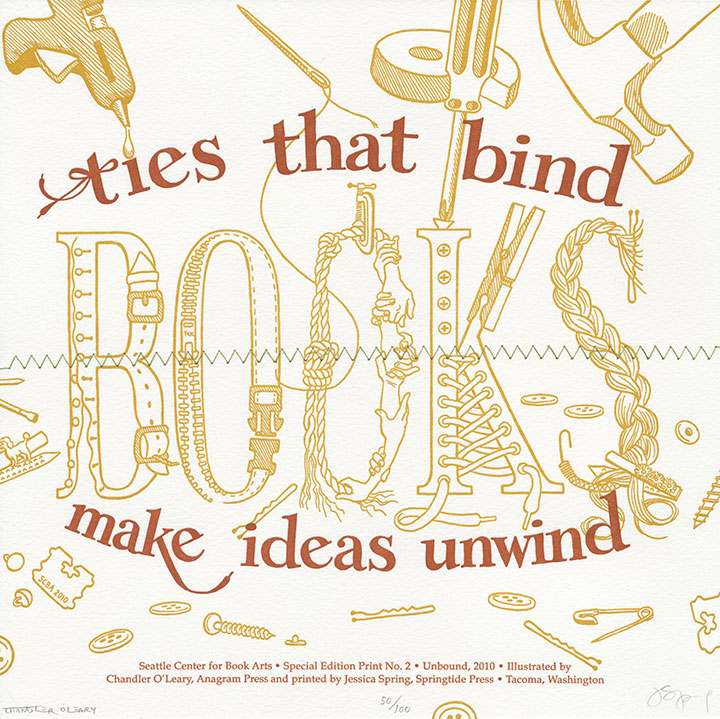

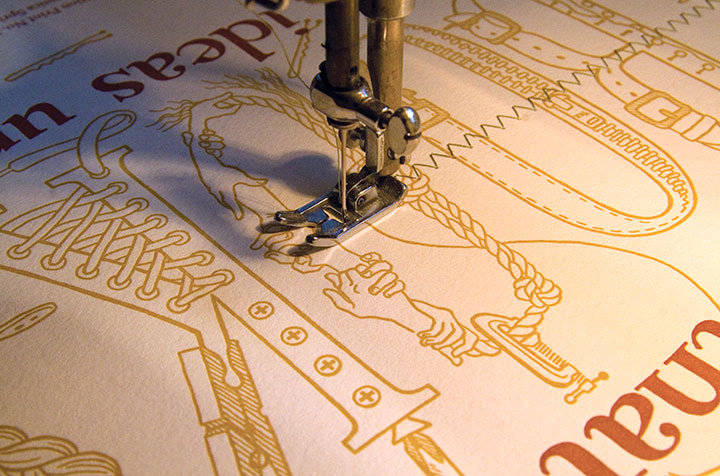

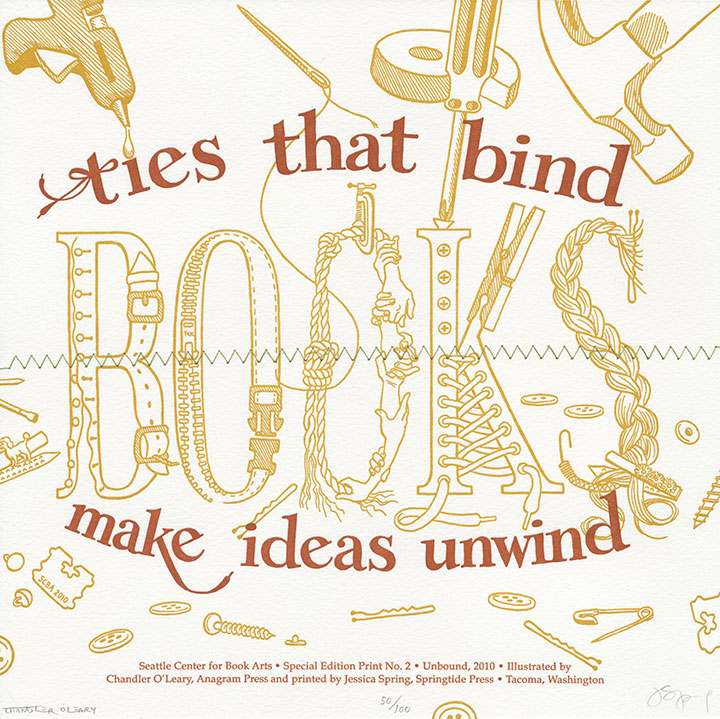

This week, though, there was a new element to the chaos: the drone of the sewing machine. And now that all the threads are tied off, Jessica and I are finally ready to unveil a little secret we’ve been sitting on for a few months. Seattle Center for Book Arts (SCBA) asked us to create their second-annual Special Edition Print, and I’m happy to report that they’re now available for sale.

Each year the Special Edition Print has the theme of “Unbound,” and the folks at SCBA challenged us to interpret it how we liked. So instead of our customary work with famous quotes, Jessica whipped up a little gem of her own. We started thinking about all the ways something (not just a book!) might be bound or unbound, which led us to visions of lacing, pinching, tying, zipping, braiding, taping, clamping, buttoning, stitching, buckling, hammering, gluing, clipping, lashing and pinning. Which then, of course, gave me free reign to make an absolute, giddy mess of things, and scatter fasteners and notions all over the page. My favorite additions to the drawing, though, are the bread tags. My grandmother had a whole drawer full of them in her kitchen (did she ever use them, or did I just discover the source of my pack-rat tendencies?), and I loved the way they rattled around in there. So Nana, this one is for you.

Everything is hand-drawn and lettered (as per usual), then letterpress printed in copper ink and an ochre color that is precisely the shade of those little Bit o’Honey candies (remember those?). This time, though, we’ve added a little extra goodie: a line of zig-zag stitching in cotton thread, in exactly the green of copper patina. SCBA is the only place to get these prints, so if you’d like to play a little game of Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button, you can get your copy here.

November 13th, 2009

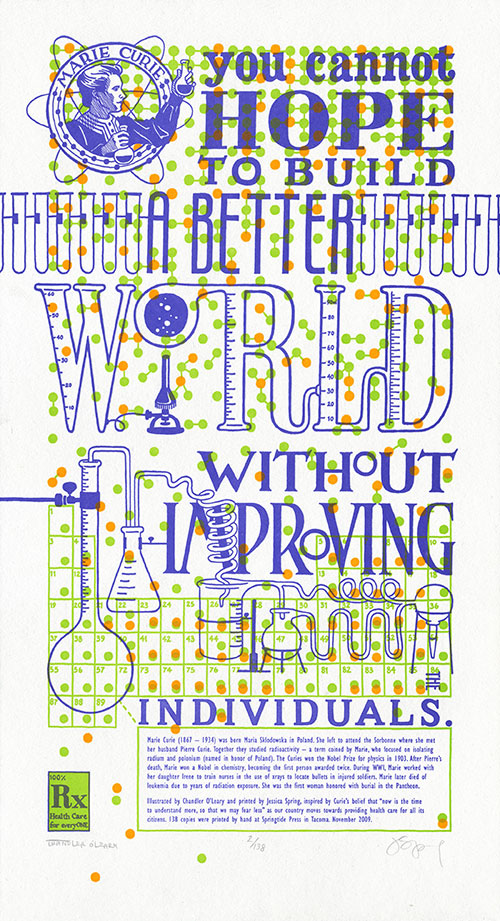

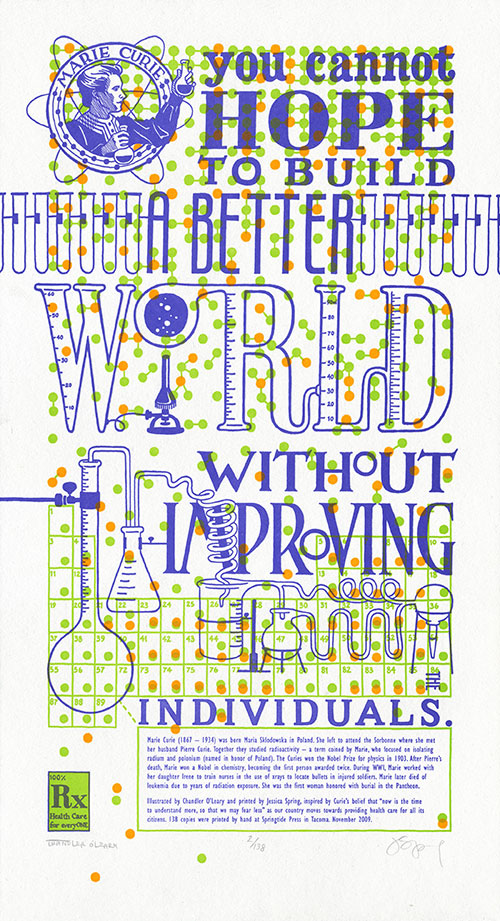

I guess it was inevitable that Jessica and I would veer back into controversial territory eventually—we’re a little ornery, after all (as if you hadn’t guessed). We’ve been sitting on this concept for several months now, and have put it off a couple of times in order to move Thea Foss and Harriet Tubman ahead in the queue. Now, though, the time feels right—or maybe we’re just so upset and keyed up by the issue at hand that we just couldn’t wait any longer. Either way, we’d like to offer our take on what a famous scientist might have had to say about health care:

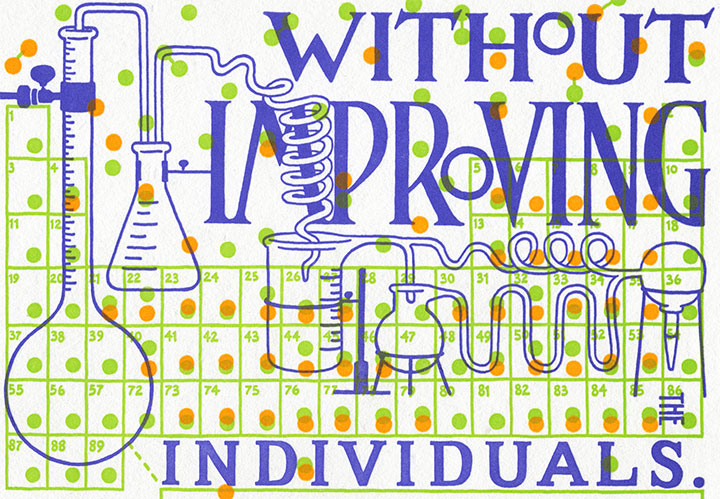

You cannot hope to build a better world without improving the individuals. —Marie Curie

I’ll spare you the ranting and raving that you can find in countless other pockets of the internet (or my house), except for one small, very personal anecdote about this topic. You see, I am self-employed, as a working artist and bona-fide small business owner. And it’s a mighty good thing that I happen to be married to someone with a full-time employer, because when I traded my graphic design day job to go full-time with my business, I also gave up access to health insurance that was anywhere near affordable. So I am on the Tailor’s health insurance, which costs us—wait for it—approximately $650 a month. That’s just to cover me, and I don’t have any “preexisting conditions” (why is it that I always want to say “preconceived notions?”) or other health problems. Since we absolutely refuse to be among the millions of uninsured, remaining able to pay for coverage is our top priority. Except that’s about to get a lot harder, because this coverage—which is provided by one of the two American “non-profit” insurance co-ops, by the way (remember the buzz about those?)—will be increasing by twenty percent come January. I don’t say this to garner attention or sympathy (don’t worry, we’re doing okay) or to ask for advice—merely to illustrate my first-hand experience of the unsustainability of the system. I won’t prolong this post by weighing in on my personal preferences for health care reform, but something, somehow, has to change.

Here’s where Marie Curie comes in. Despite being snubbed and rejected by her peers again and again, Curie devoted her life’s work (and ultimately her own health) to finding answers. And what she found not only changed our understanding of science forever, but also laid the foundation for many of the medical treatments we take for granted today.

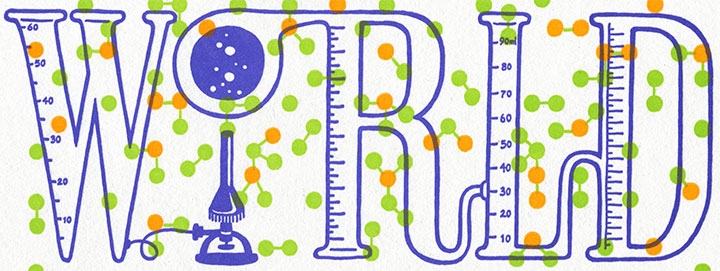

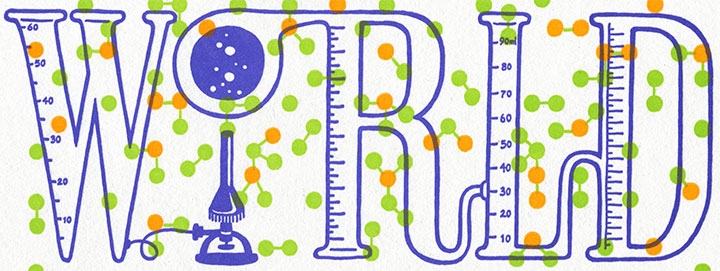

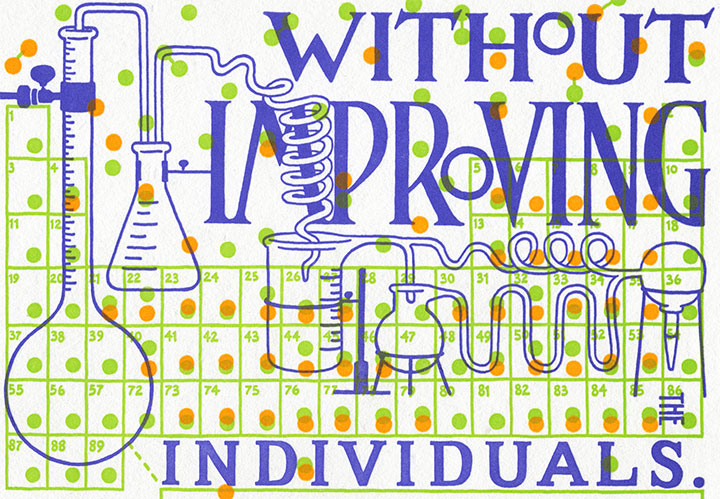

In tribute to her tireless efforts, The Curie Cure is a miasma of small details that slide in and out of focus as they compose the “bigger picture.” Each individual atom, printed in fluorescent ink, battles the text for attention—in vivid, radioactive color. The edition size is a nod to Curie’s discovery of new elements (the half life of polonium is 138 days), while the connected scientific equipment illustrates the trickle-down effect of any political action. Above all, the dominating pattern of molecule diagrams serves as a reminder that we’re all in this together.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The Curie Cure: No. 6 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 138

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, each piece is printed on archival, 100% rag, recycled paper, and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Marie Curie (1867–1934) was born Maria Sklodowska in Poland. She left to attend the Sorbonne where she met her husband Pierre Curie. Together they studied radioactivity — a term coined by Marie, who focused on isolating radium and polonium (named in honor of Poland). The Curies won the Nobel Prize for physics in 1903. After Pierre’s death, Marie won a Nobel in chemistry, becoming the first person awarded twice. During WWI, Marie, worked with her daughter Irene to train nurses in the use of xrays to locate bullets in injured soldiers. Marie later died of leukemia due to years of radiation exposure. She was the first woman honored with burial in the Pantheon.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, inspired by Curie’s belief that “now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less” as our country moves towards providing health care for all its citizens. 138 copies were printed by hand at Springtide Press in Tacoma. November 2009.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

November 5th, 2009

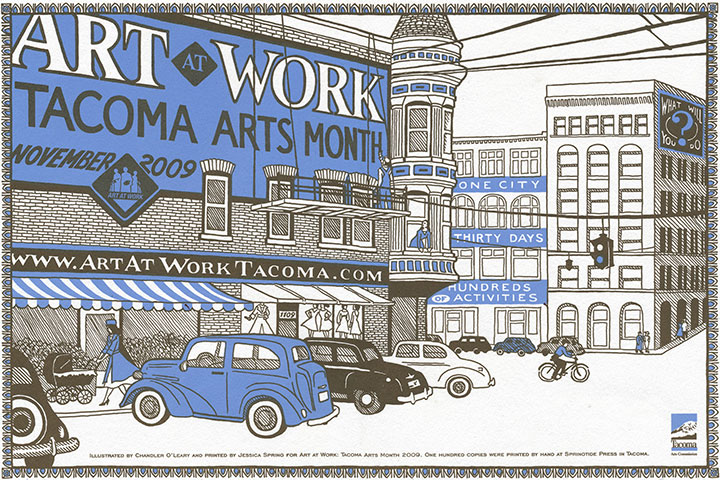

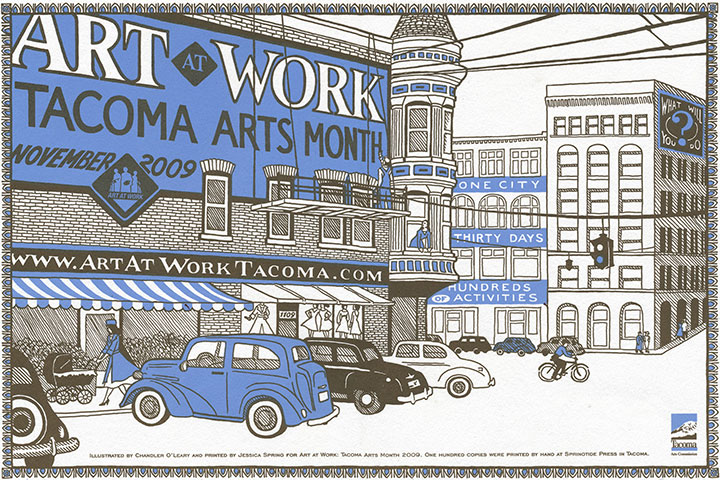

One of the biggest highlights of Tacoma’s annual Art At Work Month is the huge, city-wide Studio Tour circuit, when artists of all stripes (painters, sculptors, printers, photographers, dancers, weavers, jewelers, glassblowers, etc.) open their work spaces to the public and share their processes and products. This year (the eighth year of the event!) there are 39 stops on the tour, and yours truly is joining in on the fun.

I’ll be firing up the little Kelsey press, so stoppers-by can print their own keepsake and catch the letterpress bug (watch out, it’s contagious!),

and I’ll have lots of sketches, layouts, tools, and other process materials on display. This is the best part for me, since letterpress and artist books always bring up a lot of questions, and this time I’ll have plenty of visual aids at hand.

(Stuffed owlets by Mirka Hokkanen, another studio tour artist!)

And since the holidays are just around the corner (or already here, if you believe the Christmas muzak blaring at the grocery store; I proudly promise that Anagram Press will be a carol-free zone), there will be all kinds of goodies for sale, including a boatload of brand-new items. I’ll have copies of the Art At Work poster, a preview of nine (!) new bird prints and several holiday card designs to pre-order, and the unveiling of the newest Dead Feminist broadside. Jessica and I are featuring Marie Curie and the issue of health care this time—but that’s all we’ll share for now. Look for photos and details online next week, but if you want a head start and first pick, you’ll have to come to the tour!

Jessica will be on the tour circuit, too, at her magnificent studio Springtide Press—where she’ll be manning the Vandercook, churning out all kinds of surprises.

So grab an umbrella, ’cause it’s going to rain (are you surprised?), and take a walk around the neighborhood—Anagram Press and other participating studios will be open from 10 am to 4 pm, this Saturday and Sunday, November 7 and 8. And best of all, the event is free and open to everyone! This is my first time participating in the Studio Tours (Alec Clayton from the Weekly Volcano included me in his list of “must-see studios,” so now I’m officially nervous), so please bear with me while I work out the kinks of hosting a hundred or so guests in my little space—I’ll do my best not to run out of munchies or keepsakes. Come on by and say hello.

September 25th, 2009

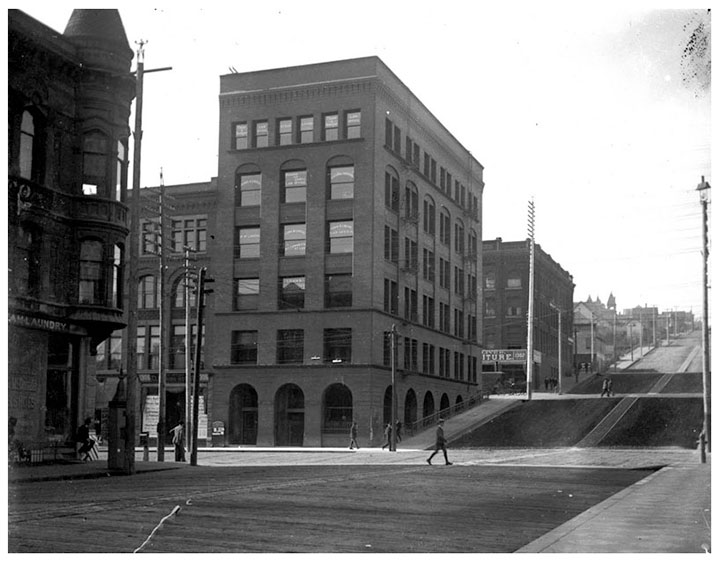

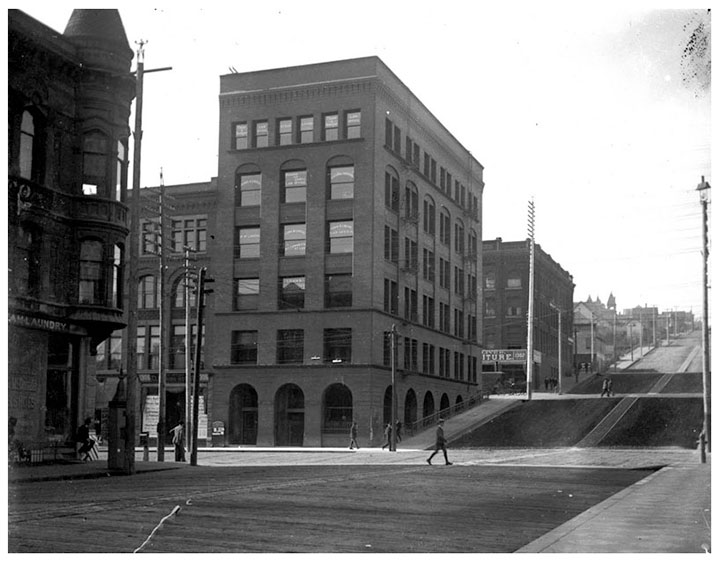

For the past several months, the buzz here in T-town has centered around the Luzon building on Pacific Avenue, a 119-year old structure that, depending on whom you ask, is either an architectural gem or a decaying eyesore. (As you can probably guess, I fall into the first category.) Above is an image of the Luzon in its infancy; this photo is printed from a turn-of-the-century glass plate negative found in Jessica Spring’s attic (and is part of her artist book, Parts Unknown). The thing about the Luzon that has made it such a sore spot around here is that it’s not just a living piece of history—at the time it was built, it was something of an engineering marvel. Co-designed by Daniel Burnham, who went on to design the Flatiron Building in New York and became one of the pioneers of modern multi-story structures, the Luzon was one of the first buildings in America to have steel columns. That makes it a direct ancestor—the great grandpappy, if you will—of the American skyscraper itself.

This is the sorry state of the Luzon today. Even though it is on the National Register of Historic Places, and is one of only two Burnham & Root buildings remaining on the West Coast, it has been allowed to decay, apparently beyond the point of no return. While each of many redevelopment schemes over several decades has fallen through, the building has become increasingly derelict. Now that the adjacent property—which provided structrual stability—is long gone, the Luzon is crumbling under its own weight. The City has even closed the surrounding streets in case of a collapse.

Oh, and there’s a tree growing out of it. I don’t think that was part of the original plan.

Well, whether it was a ploy to get around the Historic Register for a development scheme, or the powers that be just dragged their feet for too long (or some combination thereof), the detractors are finally getting their wish. The building is slated for demolition tomorrow morning. So now everyone (including me) has got the Luzon on the brain.

Last week the inimitable artist/cartoonist RR Anderson (who has a few choice words himself about the Luzon’s fate) challenged me to compete in his weekly sidewalk chalk contest, the Frost Park Chalk Challenge. I was looking for an outlet for my Luzon frustration, so I accepted. I grabbed a hunk of charcoal, a handful of communal Crayola chalk, and headed for a highly visible chunk of concrete wall to create a public altarpiece.

Photo by R.R. Anderson

My little Ascension doodle earned me a lot of comments from passers-by and the title of BEST ILLUSTRATOR IN THE UNIVERSE (OF TACOMA) for the week (thanks, guys!).

But sidewalk chalk isn’t exactly archival, and I wanted to make a somewhat more lasting statement. Here’s where letterpress comes in. Jessica and I were commissioned to design and print this year’s poster for Art At Work Month, hosted by the City. So since the theme for the overall Art At Work design this year is “ghost signs,” we decided the poster would be the perfect opportunity for a little cameo.

The original posters are letterpress printed in an edition of 100, and will be sold by the City in November, as part of the festivities. But a reproduction will also be inserted into every Art At Work brochure—over 10,000 of them. So come November Burnham’s gift to Tacoma will be long gone, but it’ll feel good to know that we did our part to make sure the Luzon is everywhere we turn—at least for a little while longer.

Edited to add: now that Art at Work month is over, you can now find the last few copies of the letterpress poster in the shop!

August 14th, 2009

For nearly a year now, the Dead Feminists series has given us an outlet for both our aspirations and frustrations. For every social and political victory, there follows a reminder of how divided we are as a culture. We were so proud to see Victory Garden become a part of a nation-wide movement toward sustainability—but a movement and a majority are not the same thing. We are delighted whenever a customer tells us that Prop Cake is meant for a wedding gift—but are heartbroken by the reminder that for many people, the gesture can only be symbolic. Yet through it all we remain optimistic that art can make a difference—that a bright future is out there, somewhere, and that we can help find the way to it.

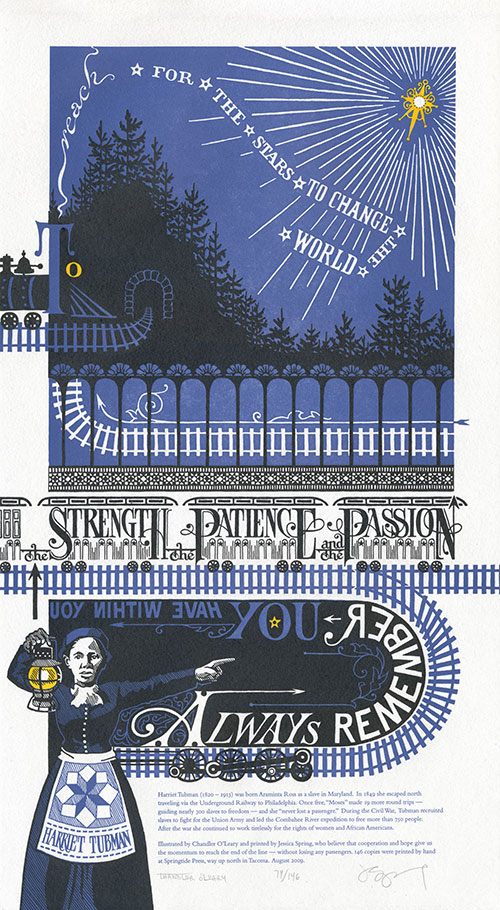

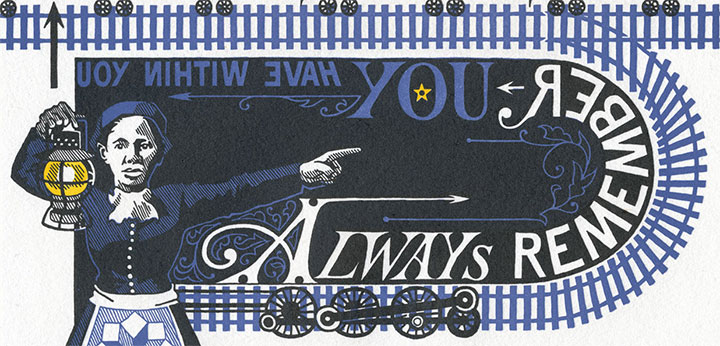

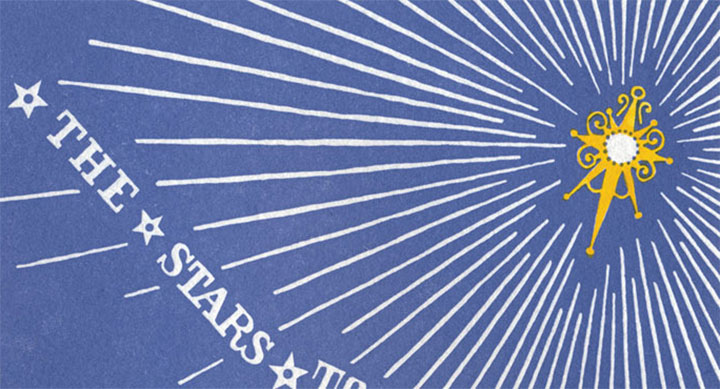

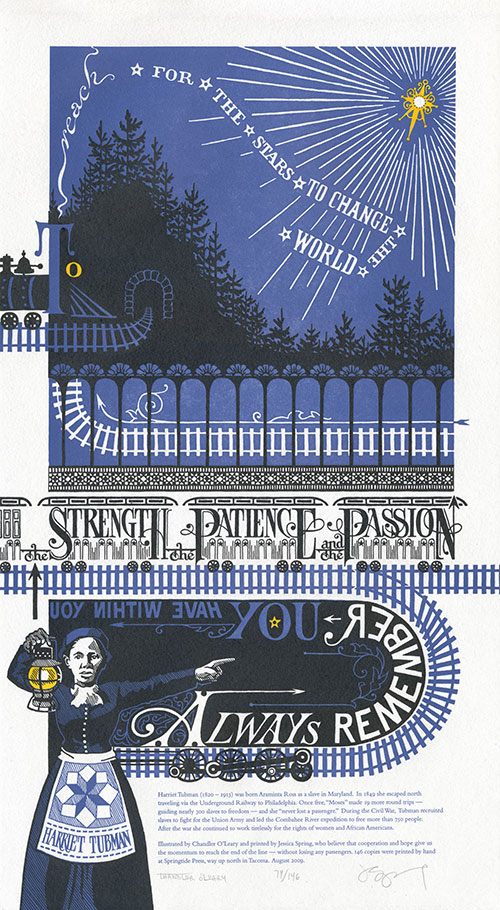

Always remember you have within you the strength, the patience and the passion to reach for the stars to change the world.

— Harriet Tubman

This is why we chose Harriet Tubman for our latest piece. There are so many pressing issues vying for our attention—war, the economy, healthcare, the environment, transit, equality, etc.—that we couldn’t choose just one. So we decided to focus on the journey itself. For all the ground we’ve gained in our country’s short history, we have a long, long way to go—and the only way we’ll get there is together. Harriet Tubman knew that when she fought for freedom and civil rights, and she devoted her entire life to the idea.

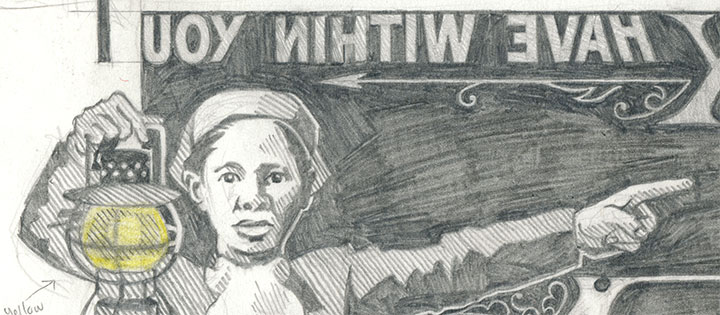

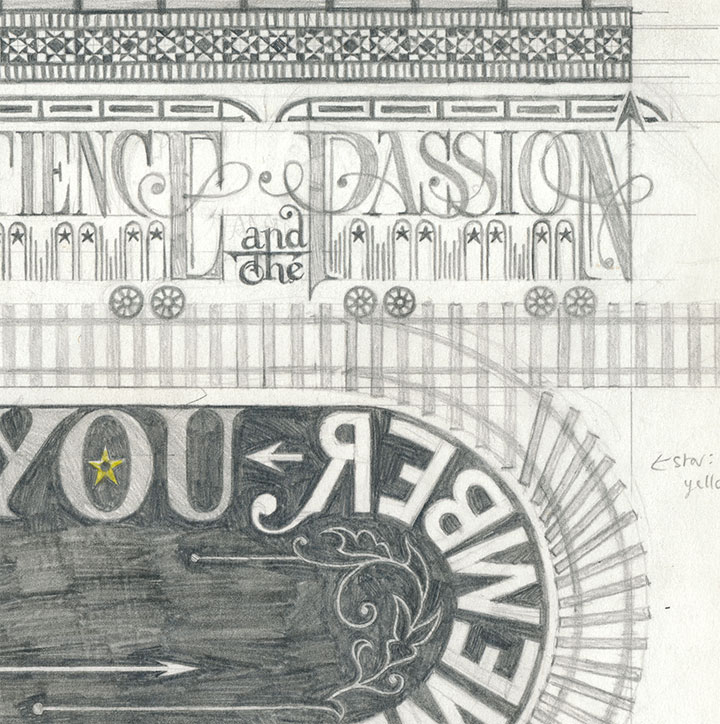

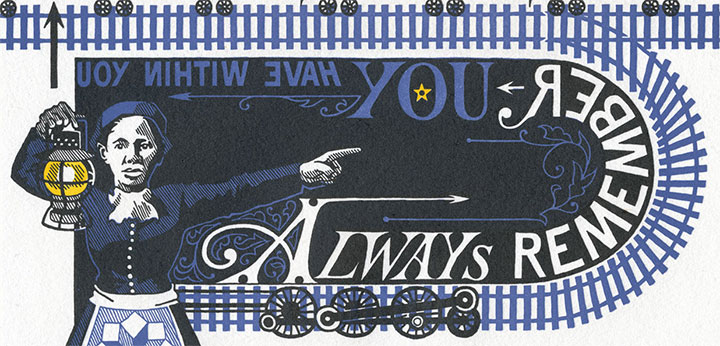

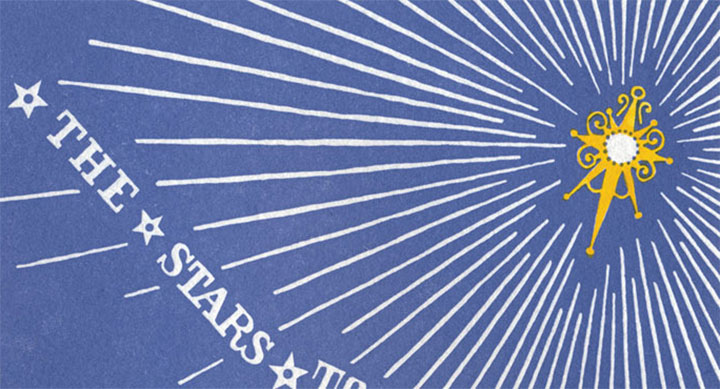

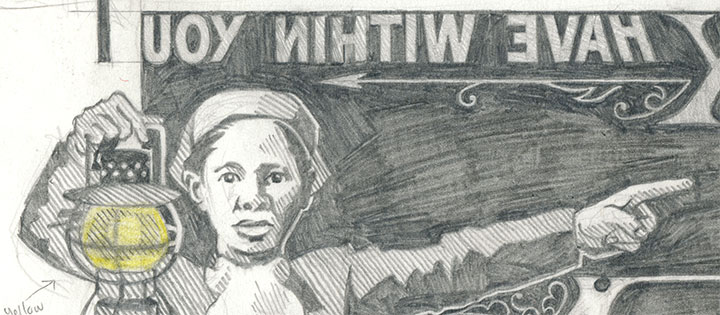

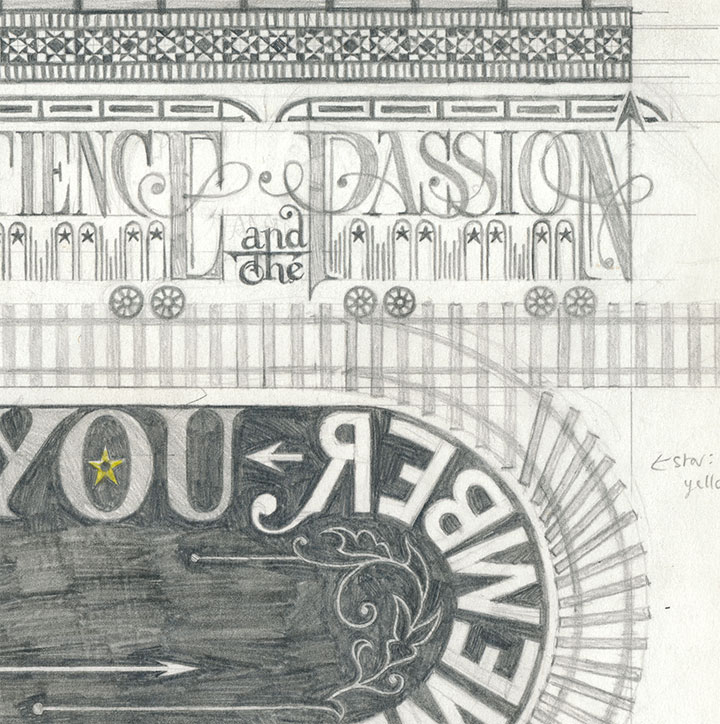

So here, submitted for your approval, is End of the Line. As always, everything—from the illustrated lettering to the letterpress printing—is done completely by hand. This time, though, we’re asking you to flex your reading muscles a bit: to symbolize the difficult journey faced by anyone with a great task, we made it somewhat of a challenge to read.

Don’t worry, though—Harriet is there to guide you. Just follow her lantern, and you’ll find the right path. If you lose your way, just look for the Drinkin’ Gourd.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

End of the Line: No. 5 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 146

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press and hand-colored with watercolor. Each piece is printed on archival, 100% rag, recycled paper, and signed by both artists.

Colophon:

Harriet Tubman (1820 – 1913) was born Araminta Ross as a slave in Maryland. In 1849 she escaped north traveling via the Underground Railway to Philadelphia. Once free, “Moses” made 19 more round trips—guiding nearly 300 slaves to freedom—and she “never lost a passenger.” During the Civil War, Tubman recruited slaves to fight for the Union Army and led the Combahee River expedition to free more than 750 people. After the war she continued to work tirelessly for the rights of women and African Americans.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, who believe that cooperation and hope give us the momentum to reach the end of the line—without losing any passengers.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

August 12th, 2009

Jessica and I are almost ready to unveil the next Dead Feminist broadside! The ink is drying as I speak, so End of the Line will be available this Friday, August 14. For now, this is just a taste. Brush up on your mirror-reading skills, because this one is going to be a challenge. Stay tuned!

May 16th, 2009

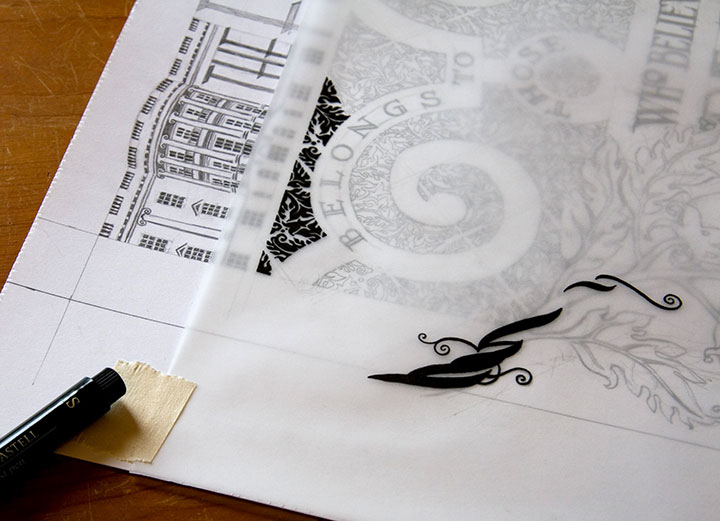

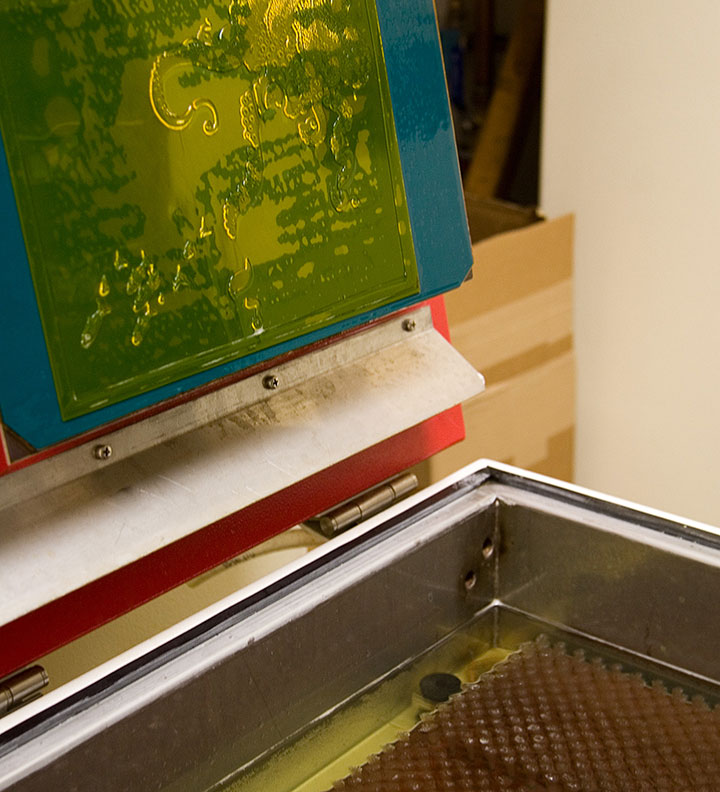

When it comes to letterpress printing, process is everything. And since that process is not always evident in the final product, I thought I’d share the technical aspects of the Dead Feminists series. Now, as I said in the last post, letterpress printing is traditionally done using metal or wooden type—or in the case of the photo above, relief images cut into type-high (.918 inches in the US and UK, in case you wondered) blocks. What Jessica and I have been doing, however, ain’t your grandpa’s letterpress. Thanks to a fairly new technology called photopolymer, we’re able to create our own relief plates right in the studio, without having to carve a block by hand or etch a plate with nasty chemicals. Photopolymer has also created a bridge between the traditional print shop and the modern digital world—as you’ll see in a moment. As far as the Dead Feminists go, Jessica and I still have both feet firmly planted in the traditional world—we just dip a toe into the digital realm now and again. Here, let me explain.

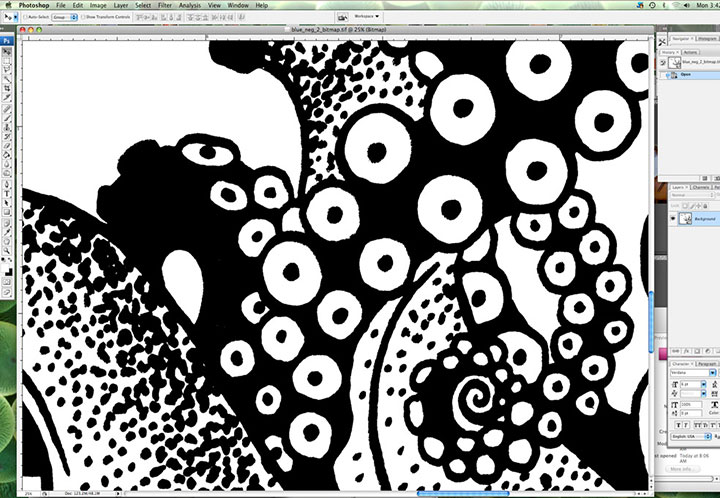

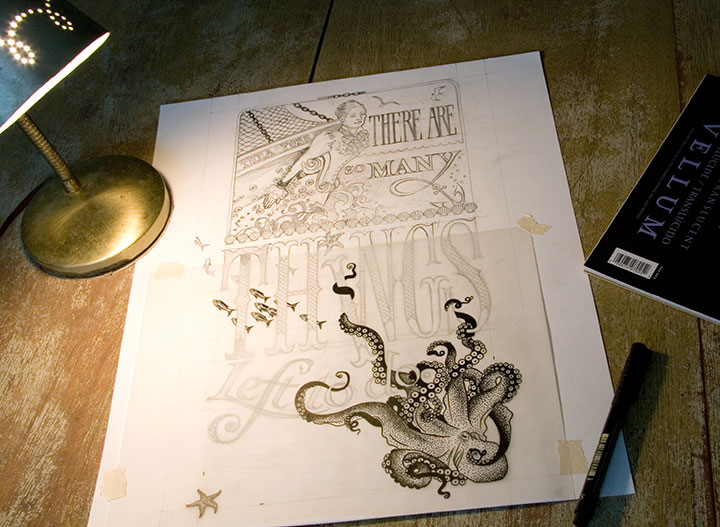

This is how it begins for each print: a pencil drawing, at full size. This is the stage where I not only design and illustrate the piece, but also start thinking about color choices: what the colors will be, what element will be which color, where the colors will overlap, how to make things work logistically. Now, this pencil layout isn’t enough to make a plate; for the photopolymer process to work properly, I have to translate the sketch into a solid black-and-white ink drawing.

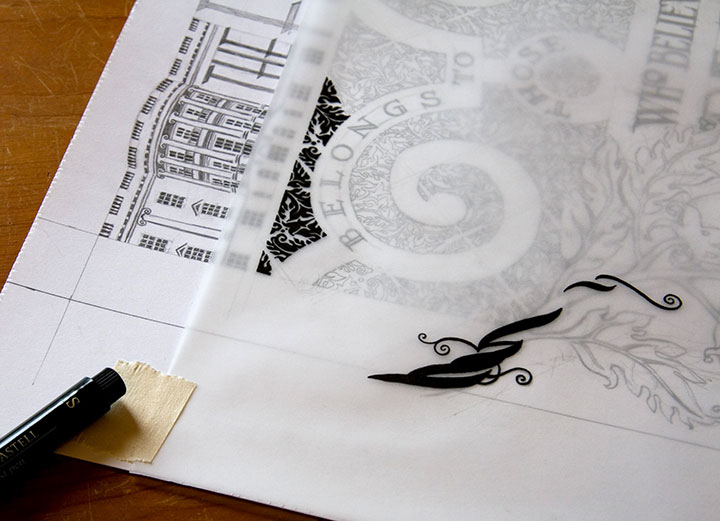

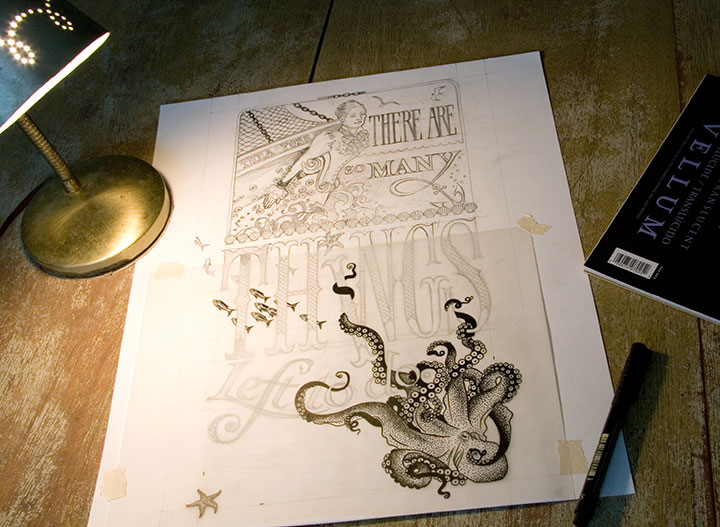

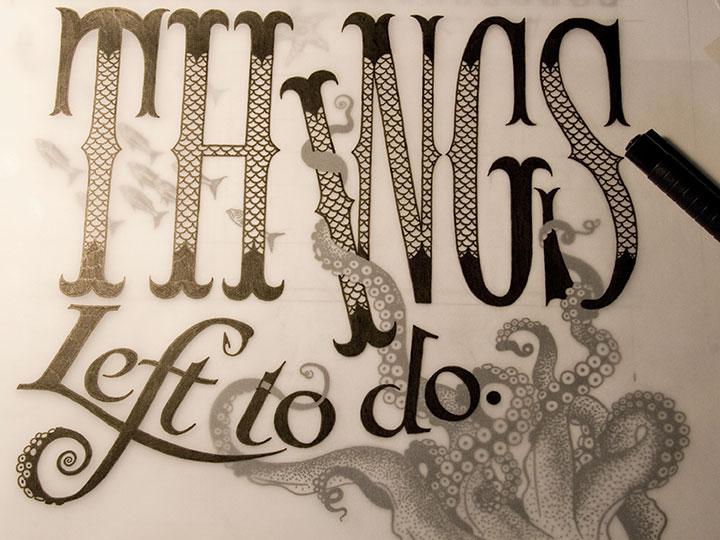

After everything is pencilled in, I lay a sheet of vellum over the drawing and trace everything in ink.

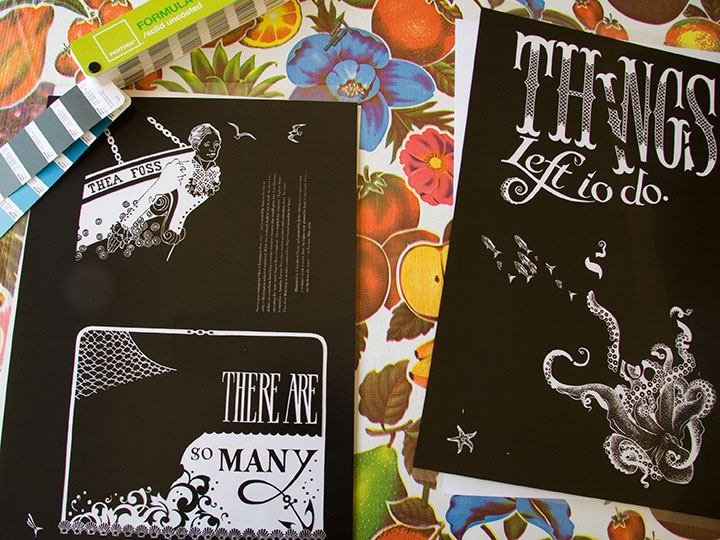

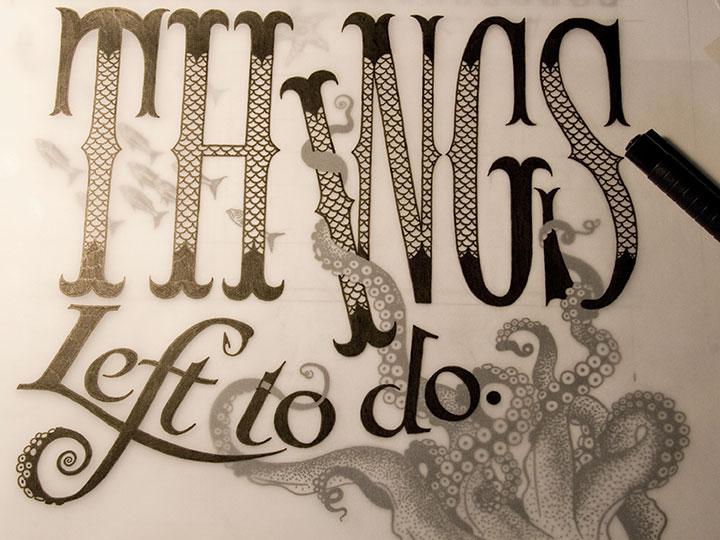

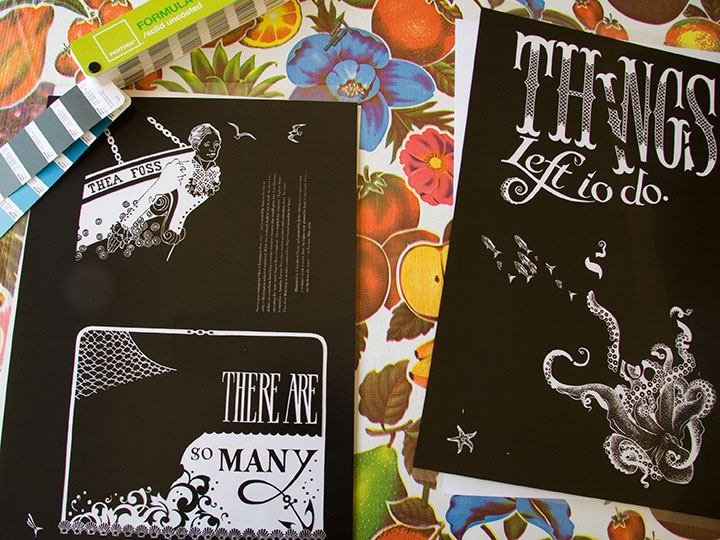

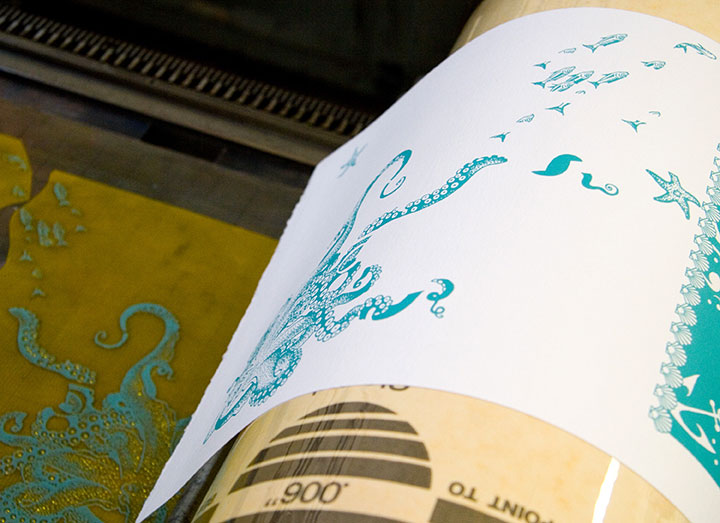

Since each broadside is printed in two colors, each color means a separate run through the press. So as a result, I had to trace each color separately—being careful to stay as true as possible to the original drawing, since the colors had to line up exactly on press. If you were to line these two color separations up, on top of one another, you’d see how the colors will interact in the final piece.

Here’s what I mean. You can see the separation that will become the grey color in Tugboat Thea here, laid directly over the inked octopus below. This is definitely the old-fashioned way of doing things; there are plenty of digital methods of color separation. I guess I just prefer the physical connection between the pen and the hand—even despite the greater risk of screw-ups (as you can see if you look closely at the word “to” above).

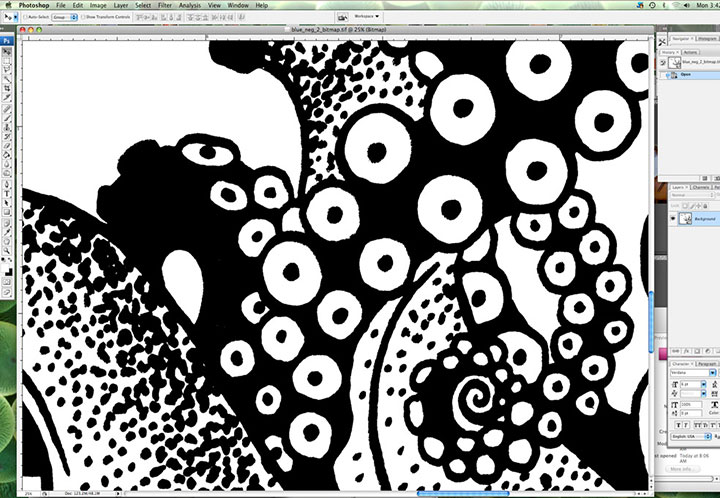

Here’s where I dip that toe into digital waters. Once I’m finished inking, I scan the finished line drawings at a super-high resolution and load them into Photoshop. This is where I clean up any mistakes (ahem) and convert the drawings into bitmap (pure black and white, with no grey) files. Jessica sends me her written colophon, and I set the text digitally. Then I export everything to the proper file type, and send the files to a local service bureau to have film negatives made. So now we’ve gone from analog to digital and back again.

Here are the negatives for Tugboat Thea; grey separation on the top half of each one, teal on the bottom. As you can see, there aren’t any right angles in the bottom half (octopus) of the teal separation, so if you look closely you can see the little tick marks I added (above and to the right of the starfish) to aid with color registration. Those marks line up with a grid etched on the metal base we use to lock up the plates on press; once we had the plates exactly where we wanted them, I simply shaved those little tick marks off with an Xacto knife, so they’d no longer print. Real slick.

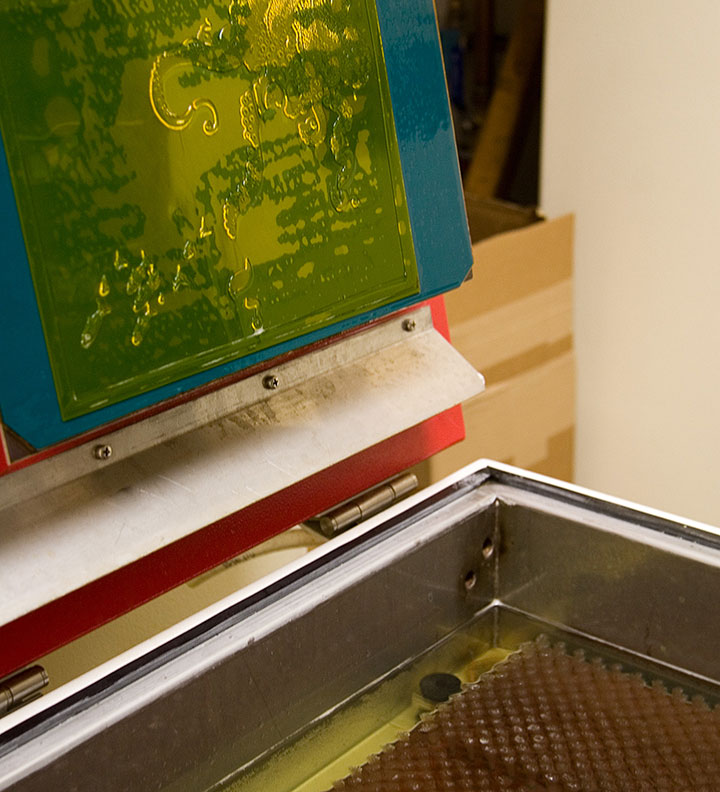

Anyway, photopolymer is a light-sensitive plastic that works just like making a contact exposure in a darkroom does. First I take a negative, place it face-down on an unexposed plate, and load both pieces onto the exposure tray of Jessica’s platemaker (which looks remarkably like an Easy-Bake Oven).

The negative is held flush with the plate by a layer of plastic and a vacuum system; the plate is exposed with UV light (some DIY enthusiasts also accomplish this using glass and a bright, sunny day, but photopolymer is awfully expensive to use in sketchy experiments in the cloudy Northwest).

Next I place the exposed plate in the wash-out unit, where it is scrubbed gently with soft bristle brushes in a tank of cool water. Everything that is exposed is hardened enough to resist scrubbing, while everything else dissolves away. (And turns the water a sickly shade of yellow. Mmmm….plastic byproducts. Still, it’s less toxic than many other printmaking techniques.)

What we’re left with is a raised plate ideal for relief printing. The real benefit of photopolymer is that it can reproduce nearly any image, and can hold an incredible amount of detail. I can transfer my drawings directly to the plate, without adding the laborious step of carving the image into wood or linoleum (backwards!), or etching copper with acid, for example. It’s not exactly an economical option for letterpress printing, but the results can be exquisite, and the possibilities are nearly endless.

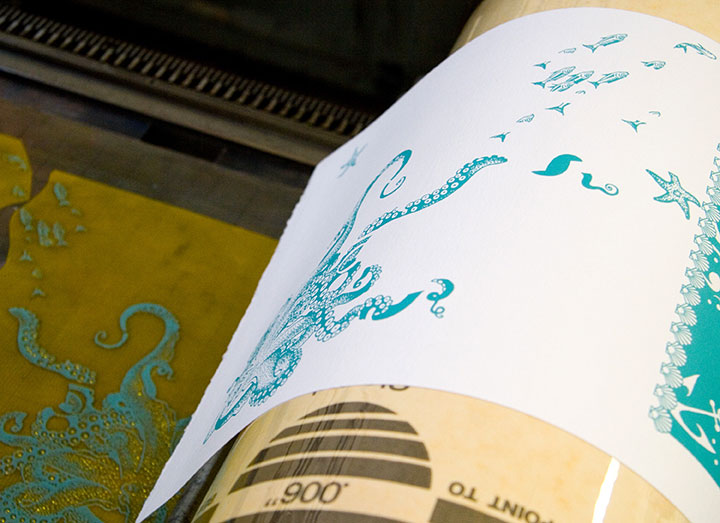

Here’s our new octopus plate on press, all inked up and ready to print—it’s stuck to that gridded base with removable adhesive. The thickness of the plate and base together add up to exactly .918 inches. Ah, precision feels good.

And here’s how it looks on paper.

Here you can see the registration between the colors. This is the hard part—I’m sure that despite my best separation efforts and useful tick marks, Jessica is ready to tear her hair out whenever she sees what insane registration issues I’ve thrown at her this time. She’s not a master printer for nothing, though—tiny, 9-point colophon type? No problem! Large, solid color blocks? Bring ’em on! Exacting registration with no margin of error? Sigh. Just get those plates locked up, will you?

Actually printing these broadsides is where all our careful planning and preparation goes right out the window. We can sketch and plot as much as we like, but many of our artistic decisions end up being made on the fly, right on press. Here Jessica is mixing ink for Prop Cake, according to some choices I suggested in our handy-dandy color recipe book.

You can see our original draw-down (color test) in the upper left corner. So far, so good.

The orange turned out exactly as we’d hoped, but when we started printing the pink separation, we hated the result. What looked so good in the draw-down lost all its contrast in the print. It was awful, trust me.

So Jessica changed the color right on press, until we were happy with it.

Here’s the finished product, all lined up in the drying rack.

If lining up the color areas is the hardest part of printing, keeping an eye on the ink consistency was probably the most fiddly. We’re using a very unusual paper for the series—one made from recycled clothing—that is extremely “thirsty.” Not only are there inconsistencies in the paper that can throw off the overall quality of color; but we had to add ink to the press after every fourth or fifth print. As you can see, this is a pretty organic process—lots of variables, small corrections and compromises along the way. (And a whole lot of cursing and starting over.)

All of this is par for the course for a letterpress project—it’s an exacting, sometimes frustrating process, but that’s what I love about it. And the finished product … well, it’s like nothing else. Ah, letterpress, how I love thee.

Now if only it didn’t require several metric tons worth of equipment…

May 14th, 2009

Holy cannoli, everyone! I’ve only just now come up for air—I’ve been buried under invoices, subscription forms, kraft mailers, and email print-outs, and Thea’s face is repeated all around me as reserved copies are spread all over the studio. Since I posted her here on Tuesday night the orders have just poured in, and over three-quarters of the edition is spoken for already. And Prop Cake is disappearing fast, too; we’re down to our last handful. Wow—just…wow. Thank you all so, so much.

Since Thea and her fellow Dead Feminists have left T-Town to be shipped all over the country (and to lovely Canada, France, Switzerland and the UK, too!), I thought it appropriate to share some of the things Jessica and I talked about at TAM the other day with a wider audience. Now, normally my paralyzing fear slight nervousness while speaking to a crowd manifests itself by wiping my memory clean immediately after I give a talk. It’s a very annoying thing, not being able to remember what you just said, but it happens all the time. I guess I’m fortunate that my phobias don’t show up as a quavering voice or profuse sweating (so nobody ever believes me when I say I get stage fright), but selective amnesia isn’t much of a fair trade for fake confidence! But this time, weirdly, it didn’t happen—I remember almost everything, and I think it’s because I wasn’t alone. (Jessica, I reckon that means you’re doomed to be my speaking partner from now on!) So to make sure my memory stays put, I’m setting it down here for the record. (By the way, since there’s rather a lot to say on the subject, I’ve decided to break it into two posts.)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

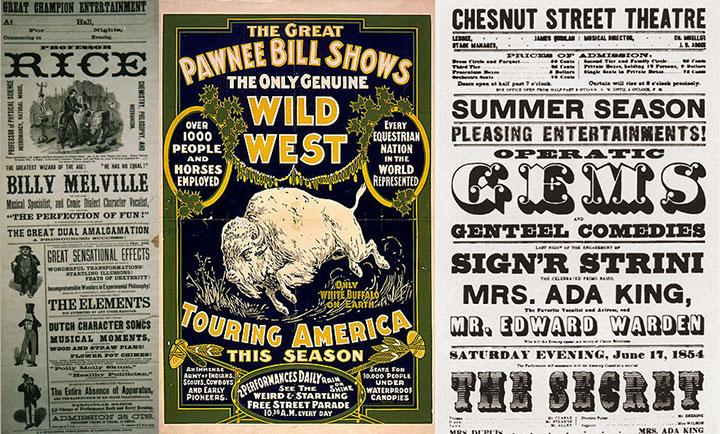

Before I get into the technical details behind our series, I should probably share a little background information on letterpress and the art of the broadside. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the process, letterpress printing refers to a type of relief printing, where pressure is applied to a piece of paper placed over a raised form that is covered with a thin layer of ink. This pressure transfers the inked image onto the paper, and can be repeated to create a batch, or edition, of prints. The form can be a carved block of wood or linoleum; a raised plate made of magnesium, photopolymer (plastic) or other materials; or as the term letterpress implies, movable type made from metal or wood.

The innovation of printing words from individual letter blocks that can be rearranged and reused was actually invented by the ancient Chinese (seriously, what wasn’t originally invented in China? We owe those folks a whole heap), but the process that evolved into modern letterpress was most famously perfected over 500 years ago by Johann Gutenberg, of Gutenberg Bible fame. By the first half of the twentieth century, when more modern commercial printing came along, it was still common for printers to perfect their layouts using movable type and relief-cut images on a proof press (such as Jessica’s Vandercook below). They’d then use the resulting print to make more sophisticated plates for their more efficient and advanced commercial presses.

Jessica printing “Prop Cake” on her Vandercook Universal One press

As commercial printing became more streamlined, the cylinder and platen proof presses (see photo above) fell out of vogue, and eventually were no longer manufactured. Artists quickly saw their potential, however, and have adopted letterpress printing as an art form—using, refurbishing and maintaining this antique equipment to create original works of art.

Hand-in-hand with letterpress printing, the art of the broadside has also survived and evolved into a modern format. The term broadside means any single sheet used to convey information, often of a political kind—the great-grandpappy of the modern poster. While today the words broadside and poster are sometimes used interchangeably, the broadside has remained a favorite of the letterpress community because of its emphasis on typography and content (hey, we need an excuse to use all that gorgeous metal type!).

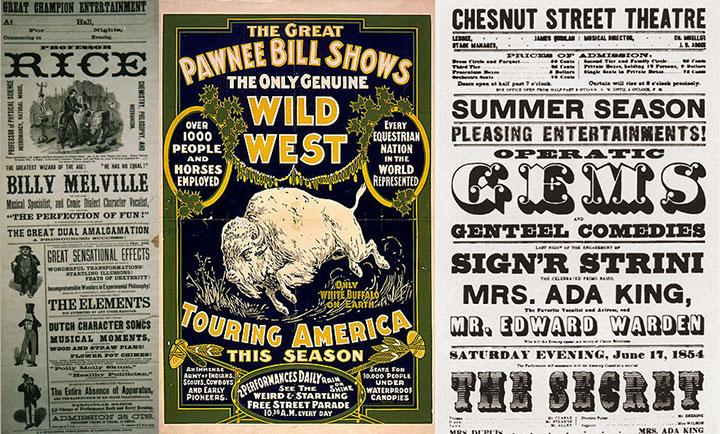

Jessica and I had this history in mind when we began the Dead Feminists series. As I said before, we never dreamed of starting down the path we’re on now; we just wanted to make a political and artistic contribution to the election. And to pay homage to the history of the broadside and the era in which each of our feminists lived, I designed each piece with historic broadsides and posters in mind. And to keep the series consistent, Jessica and I came up with a few rules of engagement:

1. Each poster has to feature a quote by a feminist. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a woman, but there are already plenty of posters highlighting the words of dudes, so we figured that one was covered already.

2. Said feminist must be deceased. (Hence the name.) You’d be surprised how many challenges that’s created for us.

3. Each quote is tied into a current sociopolitical issue or event. This is usually Jessica’s job, as she’s got a particular knack for finding relevant quotes.

4. The whole piece (except the colophon at the bottom, of course) is hand-drawn.

5. We try to stay away from well-worn tropes like “women can do anything men can do!” in favor of broader topics and concepts.

Who knows how long people will be interested in these things, or how many broadsides there’ll be in the series—all we can say is that we’re grateful for the response people have had, and we’re having way too much fun to quit now. The fun of art-making and the joy of the public response aside, the best part of creating this series has been exploring the lives and work of so many inspirational people. “Feminism” has become somewhat of a dirty word these days—mostly because of misconceptions. To us it’s a positive thing, and creating this series is our way of celebrating those who championed far more than just gender equality. Besides, we’d like to make our own contribution to our social history—and using the “power of the press” in the literal sense is the best way we know how.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Coming in part two: the nitty gritty details behind our process.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)