December 1st, 2010

You know what? It’s pretty dark here in the winter.

No, I mean really dark. Not just a sunrise-at-eight-pitch-black-by-five dark, but a kind of silver pall that sets up a permanent residence, even at midday, and makes you forget about the sun. It’s absolutely beautiful when you’re taking a walk in the fog, or curling up with your trusty Rosie mug and a hank of yarn. Not so great when you really need a lot of natural light, though—like, say, for shooting photographs…

…or mixing paint to fill in a huge stack of glorified coloring book pages.

So between the short daylight hours and a desperate need to reserve a little personal time, work on the book has slowed from a breakneck pace to a stately, clip-clopping trot. I still have so much to show you—so much to explain—but my head needs to catch up with my hands first (or is it the other way around?). I’m going, then, to break it up into a series of posts, and take a little extra time to gather my thoughts before I start. I don’t mean to string you along; because the process required working with a kind of tunnel vision for so long, I’m only just now seeing the “finished” product myself. So thanks for your patience—and for being interested enough to stick with me.

Thank you also for the huge outpouring of support you’ve shown since I posted this thing a couple of weeks ago. The comments, links, blog features, Tweets, emails, and amazing reviews are just overwhelming. I simply can’t find the words, except—thank you.

Part of what’s taking me so long is that at the same time, I’m working on a small series (like a baker’s dozen or so) of individual prints of images from the book (exhibit A above). There’s not a whole heap of rhyme or reason as to which illustrations I’ve chosen, except that these are some of my favorites. I’ll be posting them in the shop (believe me, they’ll be a lot more affordable than the book) as I finish them.

In the meantime, it’s time to light a few more lights, and keep the dark at bay so I can see what I’m doing.

Which reminds me—Happy Hanukkah!

November 10th, 2010

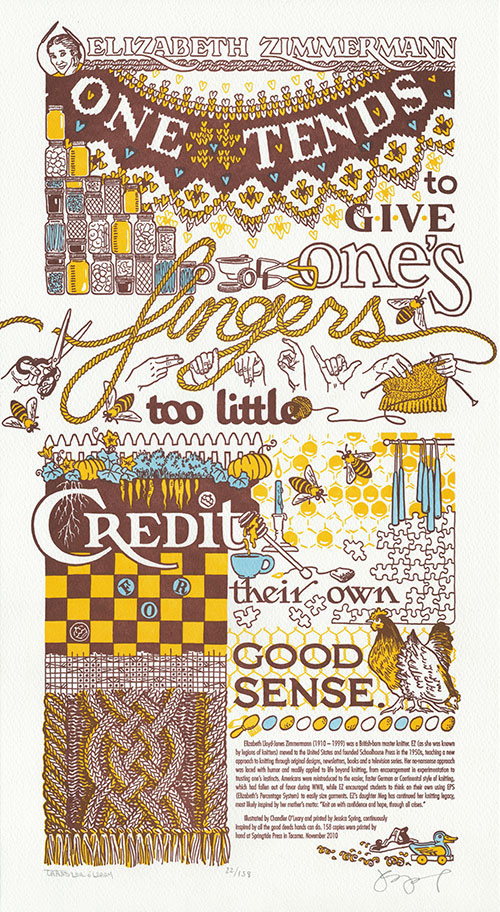

Maybe it’s the changing seasons. Or the fact that the farmers market runneth over with delicious autumn goodies. Or maybe we just wanted to talk about something that made us smile, for a change—because this time, for our tenth Dead Feminist broadside, Jessica and I have turned to a subject somewhat lighter of heart.

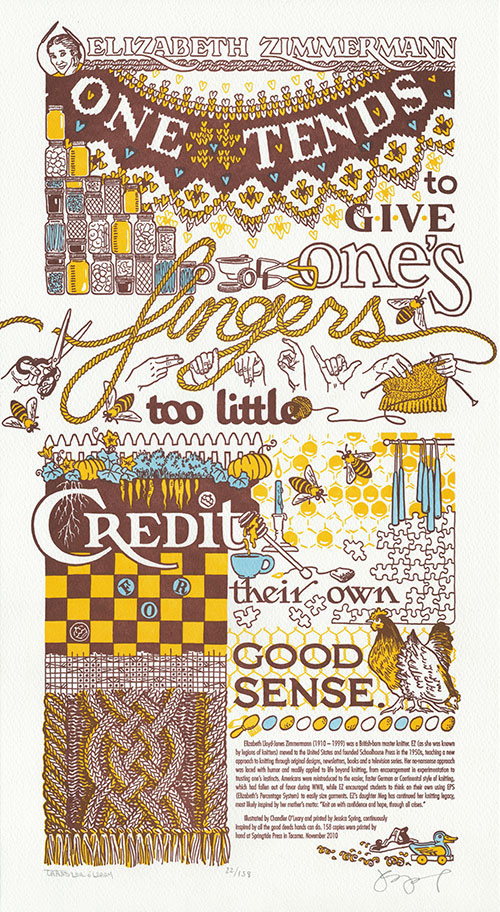

From the likes of urban homesteaders, artisans, D.I.Y.-ers, and hobbyists of all stripes, brilliant handiwork is all around us. We are in constant admiration of the power of one’s own two hands, and the good deeds they can do. And for the perfect symbol of a handmade life infused with joy and meaning, we’ve handed the microphone to Elizabeth Zimmermann:

One tends to give one’s fingers too little credit for their own good sense.

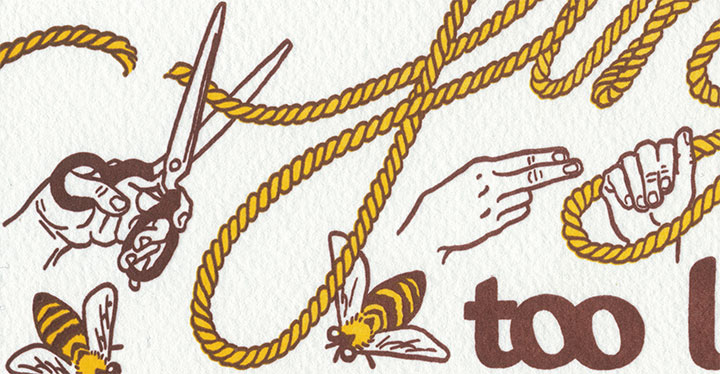

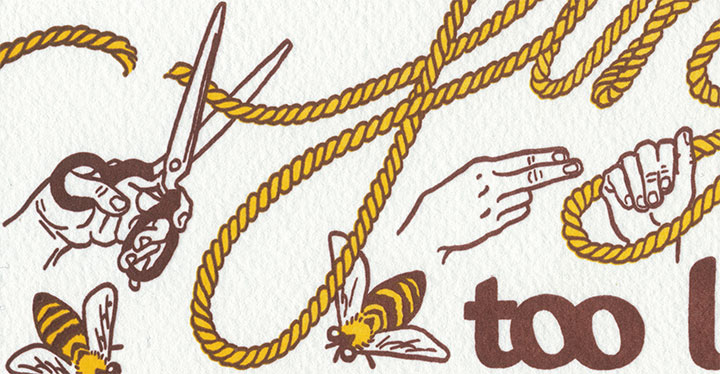

Now, as many of you probably know, Ms. Zimmermann was a knitter (that’s an understatement; I’d say more like All-Time Super-Queen Knitter of the Cosmos, Forever and Ever, Amen). But like every knitter, there is so, so much more to her than that. So rather than simply leaving it at yarn and wool, we discovered a cornucopia of the pursuits that fingers like to turn to when they’re not knitting. There are no idle hands here, to be sure.

Just in time for the fall harvest and in cozy preparation for the winter months ahead (or for our friends in the southern hemisphere, looking forward to a fruitful summer), Get Handy overflows with simple pleasures and home comforts. Elizabeth drafts a cable pattern and whips up a Fair Isle yoke. A little slow food takes root in the garden. Honeybees guard a new crop of candles. Fresh home-canned treats stock the shelves. Chickens scratch along a fence of golden (darning) eggs. Over a cup of tea, puzzles piece together and checkers crown kings. And when they’ve put down the yarn and scissors, the hands spell it out for you in American Sign Language.

Oh, and the Tailor’s blueberries and Jessica’s dilly beans make a cameo appearance. Yum.

A portion of the proceeds from Get Handy will be donated to the amazing healing hands of Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders, via Tricoteuses Sans Frontières / Knitters Without Borders, which organizes knitters to raise funds for MSF/DWB. MSF, winner of the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, is a medical relief organization dedicated to assisting people in distress around the world.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Get Handy: No. 10 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 158

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is hand-colored and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Elizabeth Lloyd-Jones Zimmermann (1910 – 1999) was a British-born master knitter. EZ (as she was known by legions of knitters) moved to the United States and founded Schoolhouse Press in the 1950s, teaching a new approach to knitting through original designs, newsletters, books and a television series. Her no-nonsense approach was laced with humor and readily applied to life beyond knitting, from encouragement in experimentation to trusting one’s own instincts. Americans were reintroduced to the easier, faster German or Continental style of knitting, which had fallen out of favor during WWII, while EZ encouraged students to think on their own using EPS (Elizabeth’s Percentage System) to easily size garments. EZ’s daughter Meg had continued her knitting legacy, most likely inspired by her mother’s motto: “Knit on with confidence and hope, through all crises.”

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

October 11th, 2010

While I’ve been hiding away, wrangling my 900-pound gorilla, Jessica has been cooking up something pretty great.

Thanks to her hard work and the wonderful Brian Hutcheson‘s invitation, we are pleased as punch to announce our first-ever dual exhibition!

Feminist Wiles: Jessica Spring and Chandler O’Leary

Now through November 5

Ted Sanford Gallery, Charles Wright Academy

7723 Chambers Creek Rd. W

Tacoma, Washington

Open 8 to 5, Monday through Friday

It seems weird that after more than two years of collaborating, giving lectures and printing in the street, we’ve never had an honest-to-goodness show together.

But when Brian offered us a cavernous space, his help with installation, and the chance to indoctrinate the innocent introduce our series to the kids at Charles Wright—well, we’d be nuts to pass that up.

For the first time, all nine (and-a-half) Dead Feminist broadsides to date, plus our two steamroller gals, are on display together.

We also have a little mini-exhibit about our process,

and lots of little goodies to introduce people to letterpress.

Jessica and I have rounded out the collection with solo work that complements the theme of the show. Jessica’s half consists of Do You Feel Beautiful?, a series of broadsides featuring famous aphorisms on beauty. Here’s the thing that blows my mind into tiny pieces every time I think of it: the quotes are letterpress printed on the pages of a Braille edition of Seventeen magazine. Whoa.

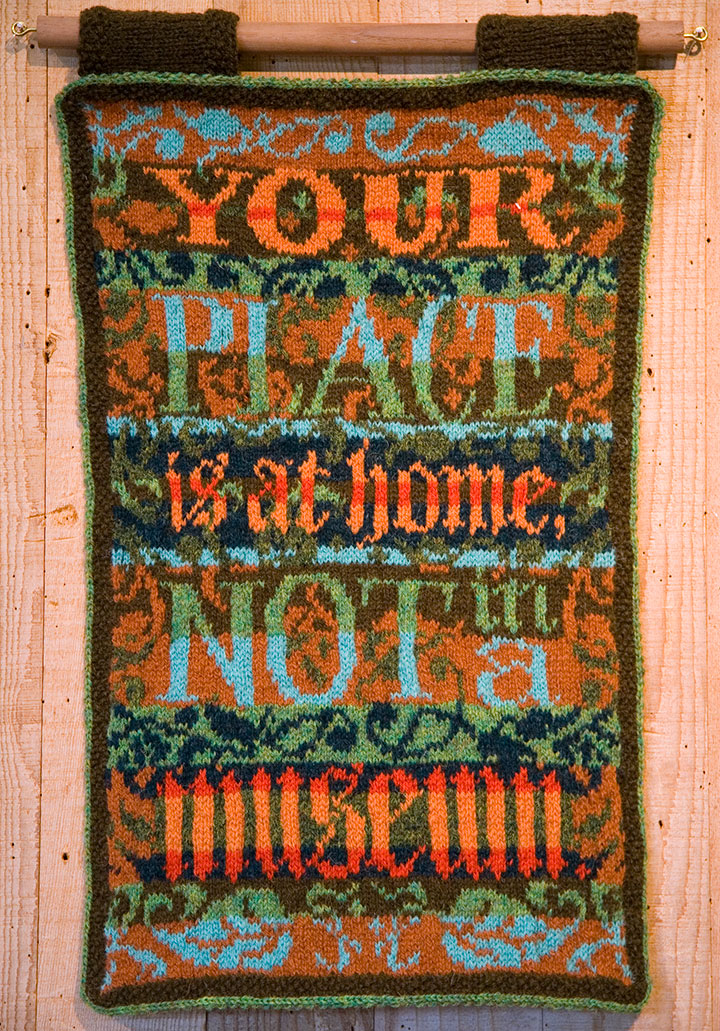

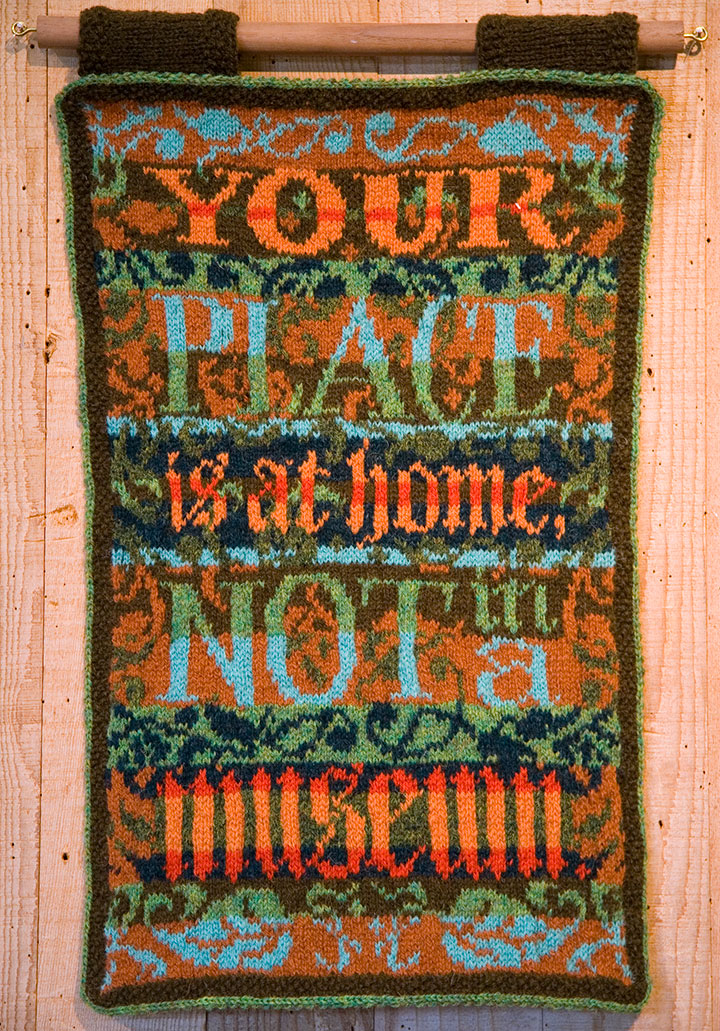

I contributed Women’s Work, an ongoing series of broadsides created in hand-sewn textiles rather than my usual letterpress.

Now, I get a ton of questions about these things whenever I show them, so I thought I’d outline the ideas and process behind them here.

The Tailor first sparked the idea for the series; as you know, he makes his own clothing (hence the nickname). This is a feat that never ceases to amaze me, and I’m not the only one—he gets a lot of comments, usually along the lines of “Wow, you made that?” He’s always a little surprised by these comments, because where he grew up, a lot of people (including his family) wore homemade clothing. That got me thinking, though. The people who do all that sewing in the Tailor’s hometown are women—mothers, grandmothers, sisters, daughters, wives. We’re all surrounded and preceded by generations of women who sew clothing, or knit sweaters, or draft patterns from scratch, without any rave reviews—or any comment at all. But every male knitter or quilter I’ve known, every rare and wonderful man who ever picked up a needle, is either looked at like he’s nuts, or treated with reverent awe. It strikes me as a little strange that depending on who made it, and who’s looking at it, a pair of pants can be a work of art—and an actual work of art can be completely ignored.

If you go further back, like, I dunno, throughout the entirety of human history—you’ll find that both men and women have been responsible for creating textile goods in nearly every culture on earth. Yet in almost every case, when men made textiles it was as part of some sort of guild craft or other professional setting. When women made textiles, it was as part of the home front. This is true in every part of the globe, in pretty much every era, going back to the advent of textile technology.

No matter who does the stitching, there’s an enormous amount of technical skill and design sensibility required to make a garment or textile object. So instead of creating divisions and pigeonholes—instead of separating into Art and Not Art, into Man-made and Woman-made, what if we started seeing the inherent worth in the objects themselves? And what happens when we take a handmade textile and stick it in a gallery? Does its perception change?

Based on what I’ve seen so far with these broadsides, I’d say it does. It’s been an interesting experiment, for sure.

So the Women’s Work series is a bit of an indictment of the double standard, and while the snark is aimed at a wider target, I wrote them as if I were speaking to a woman. Each one is completely made/knitted/sewn/pieced/embroidered/etc. by hand, from design to pattern to construction. The text reads in the voice of a disapproving female role model (or the insidious voice inside our own heads)—in the tone of the backhanded compliment, the cheerful put-down. Each is also designed in the style of a traditional letterpress broadside, to put the typography within the context of an art form centered around mass communication.

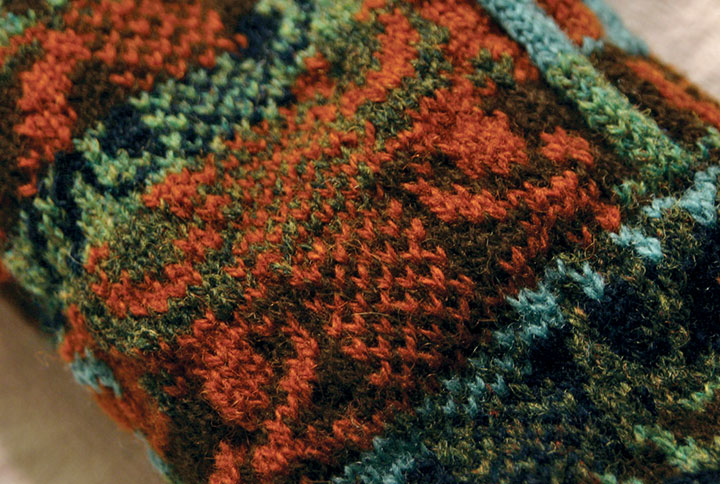

This guy requires a little more of an explanation for folks who aren’t already into wool.

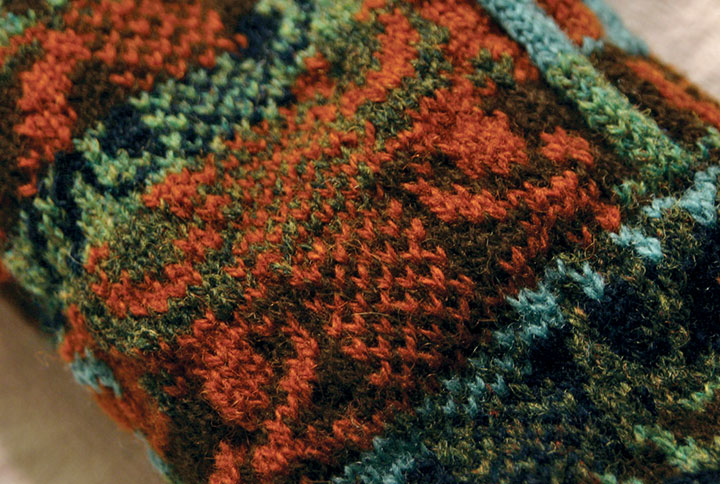

This piece, made almost three years ago now, is hand-knitted with Shetland wool, using the traditional Fair Isle knitting technique. Fair Isle—a method practiced since the nineteenth century on the tiny island of the same name, halfway between Scotland and Norway—is a tricky, rather ingenious thing. Traditional Fair Isle pieces are knit with two colors of yarn at the same time; the resulting fabric is durable, extremely warm, and great for any chilly, foggy, wet climate (like, hello, here). Beyond its über-practicality, Fair Isle knitting is simply gorgeous (take a gander at Google). By nature the double-thick fabric is dense and flat, making it an ideal ground for complex patterns and designs—it’s the perfect mix of function and fancy.

Here’s how it works: even though the piece is knitted with two different colors of yarn at once, only one strand at a time ever passes through the needles. The unused strand of yarn is carried loosely, or “floated,” behind the work—which creates a reversed-out image of the design on the back of the piece. It’s the floats that give structure to the fabric, and make it so cozy-warm.

If you were to create a plain ol’ piece of ordinary knitting, you’d proceed from one end to the other of a row, flip the piece over, and work back the other direction. Rinse and repeat. If you tried that with a piece of Fair Isle knitting, working the “wrong” side would be extremely difficult, since the floats would now be facing you and covering your stitches. Now comes the tricky, smarty-pants part. Flat Fair Isle pieces are first knitted up into a big round tube, and then cut to lie flat. When you knit in the round, you never encounter the wrong side of the work. You just spiral around and around on the right side, happily knitting away and floating the unused color behind you as you go.

So in this case, once I had drafted my design into a gridded stitch pattern, I just pretended I was knitting one really big sleeve (or a neck warmer for a giraffe) with really teeny needles.

Ah, but remember the operative words above: you have to cut the piece to finish it. I had never done this before, and let me tell you, there’s an awful, terrifying finality to the idea. Torn sweaters unravel. Snagged socks fall apart. Who in their right mind would cut a piece of knitting on purpose? And even if you could do it, what happens if you make a mistake? Once you make that cut, you’re done.

This is where the true brilliance of the technique hit me like a ton of bricks. The Scotswomen of Fair Isle are a breed apart—and so are their sheep. Shetland wool, the material traditionally used in Fair Isle knitting, has a magical property that makes this crazy notion work: each wool fiber is covered with microscopic scales that attach to one another. Because the wool sticks to itself, the stitches become slightly matted as you knit. So following the Fair Isle method, you work a little buffer zone called a steek (see the checkerboard strip above?) into your design, and then cut right down the center of the steek. If you use trusty Shetland wool, your stitches won’t unravel when you cut them.

At least, that was the theory. I didn’t quite believe it at the time. But I’d come this far—I didn’t want to lose faith. (If you’re looking to try Fair Isle knitting yourself, I find a glass of wine helps.) So I took a steadying swig, held my breath, and cut.

And then I exhaled. And blinked. I had a flat piece. Gingerly I tested the cut edge—and was amazed. Even with a fair bit of tugging, the stitches refused to unravel.

I will never question a Scotswoman again.

My favorite thing about all of this, beyond the magic of Fair Isle itself, is that knitting really lends itself well to letterforms. Even though the pattern is drafted out on a grid, the forgiving nature of knitted stitches turns every square on the grid into a slightly curved, irregular shape. So when you zoom out and look at the piece from a distance, those grid “pixels” turn into nice little serifs, curves and curlicues.

The rest of the broadsides in the series are made using other types of needlework (more on that in the next post), but the knitted piece is still my favorite. I think I need another dose of that Fair Isle magic in my life—maybe next year you’ll find me up to my knees in wool again.

(Read about the rest of the “Women’s Work” broadsides in part two.)

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)