Blog

October 22nd, 2010

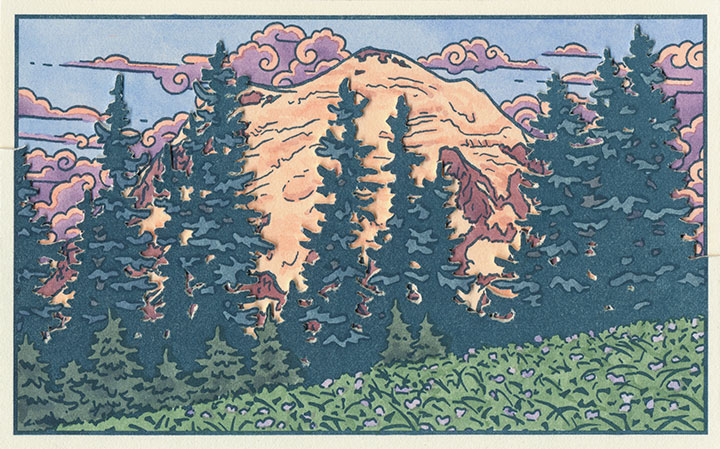

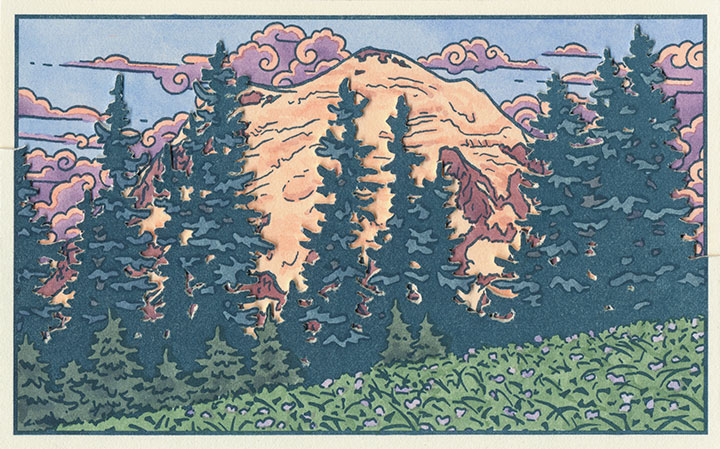

It’s getting harder and harder to keep the secret these days—the Rainier book is almost done, and I’m just dying to show you. But I don’t want to ruin the surprise for T-town, so I’m going to keep it under my hat for just a little longer. But after over two years of being under wraps, the book is gussying it up and stepping out for a solo exhibition. Here’s a brief description of what you’ll see:

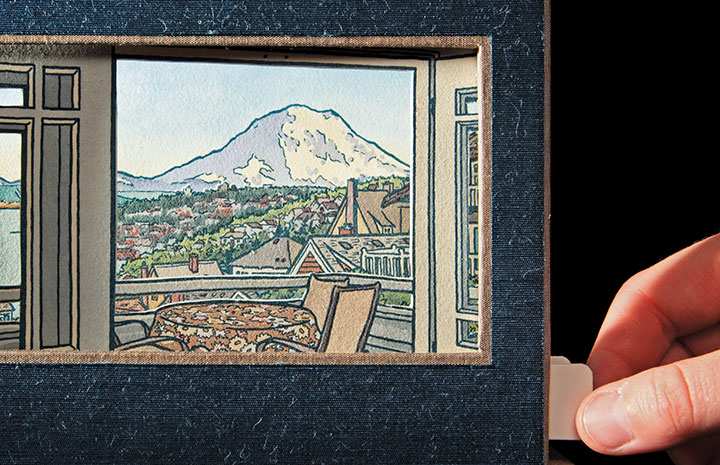

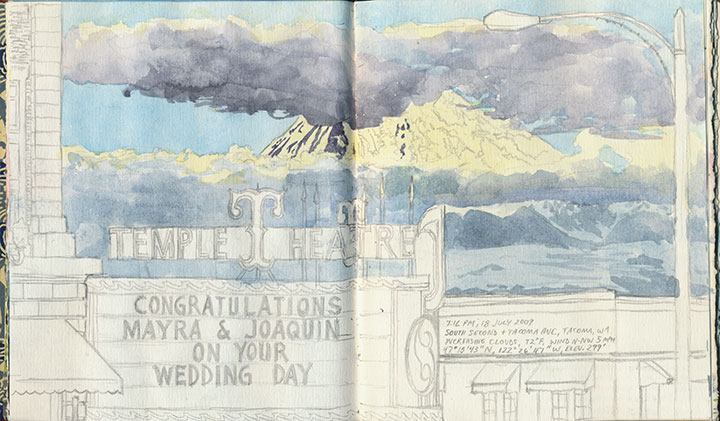

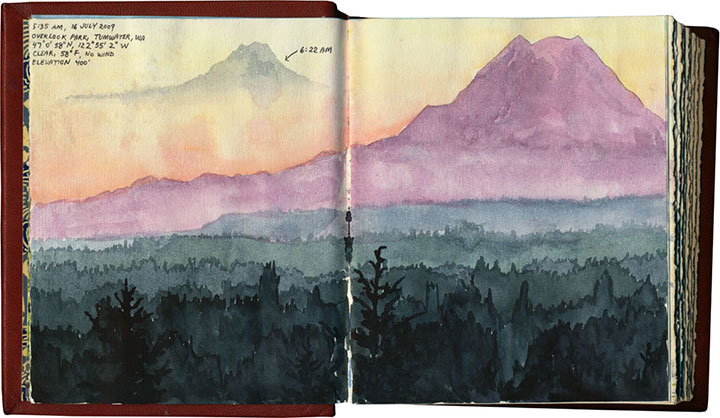

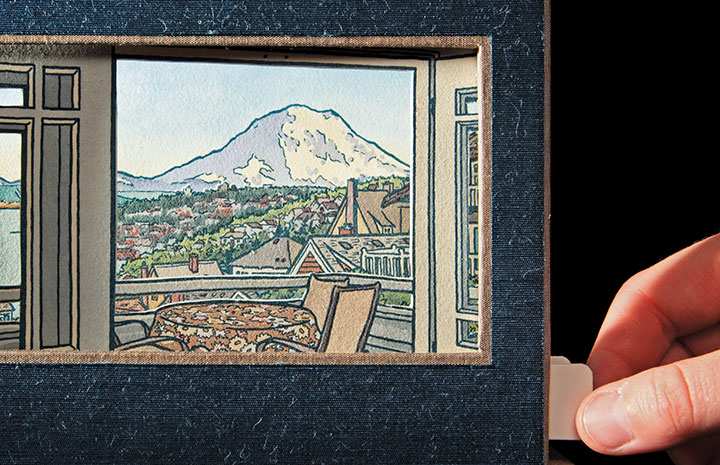

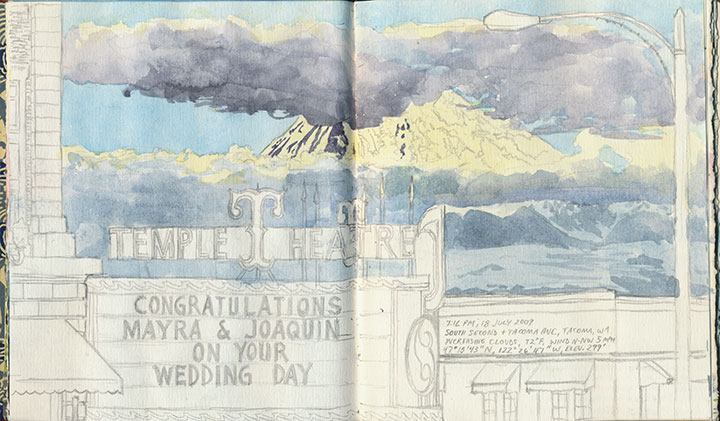

Local Conditions, an interactive artist book, captures the changing faces of Mt. Rainier. Explore the 100 Views—or create one of your own—to discover a mountain both immortal and impermanent.

The book contains 120 image flats and a viewing box; by combining and layering the flats, the reader can create literally millions of scenes. Images are illustrated and compiled from data collected in person, on location, over the course of two years. Letterpress printed, watercolored, and hand-bound in an edition of 26 books. Sponsored by the Tacoma Arts Commission.

Exhibit runs November 4 through January 21

Collins Memorial Library, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA

Opening reception: Thursday, November 4, 4:30 to 6:30 p.m.

Artist talk (sponsored by the Book Arts Guild): Thursday, November 11, 7 p.m., Room 020

Photo by Sarah Christianson

If you miss the exhibition opening, I’ll have some of the process materials from the book out for perusal at this year’s Studio Tour—as well as the brand new Dead Feminist broadside! (Look for it online in early November.) So be sure to stop by!

Saturday and Sunday, November 6 and 7

Open 10 am to 4 pm.

More information, maps, addresses and directions can be found here.

See you then!

September 15th, 2010

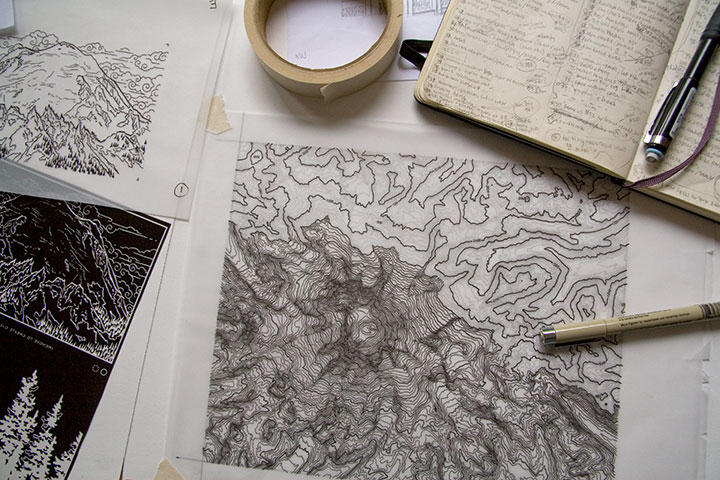

Lately I’ve spent nearly every waking minute of each day with my face an inch away from the drafting table.

Let’s step back, and stretch out a bit.

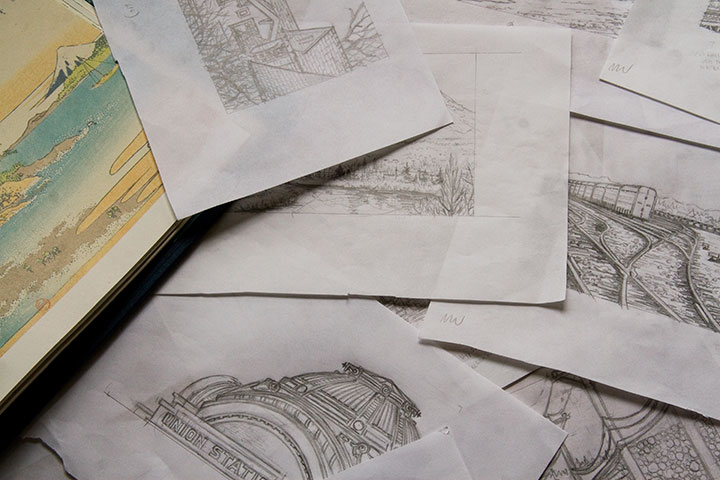

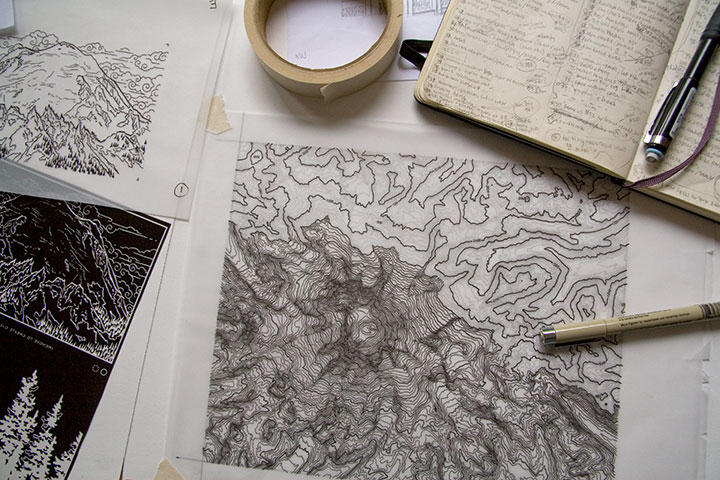

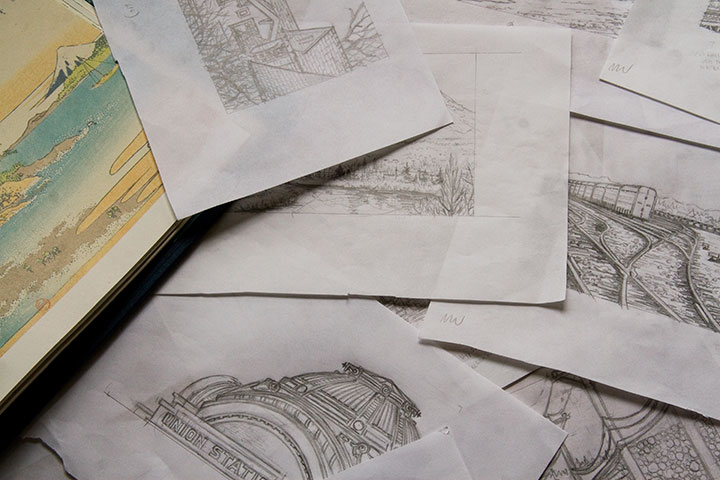

My studio is often a sea of papers—an occupational hazard—but these days the swells have consisted of pencil snapshots for my Mt. Rainier book. Dozens, and dozens, and dozens of them.

Time is ticking down, counting closer and closer to zero, and there are still many miles to cover before the clock strikes deadline. Yet suddenly, things are starting to come together. It won’t be long until I can share something that makes sense—something that looks more like a book, and less like a pile of drawings. I promise that you’ll be among the first to see it when I do.

But if I go missing for long stretches at a time—well, you know where to find me.

May 18th, 2010

I’ve had volcanoes on the brain for nearly two years. Littering my studio are volumes of sketches, nearly 6,000 photographs, reference books, stacks of maps, and a brand new, functional prototype of the artist book about Mt. Rainier I’m working on—all evidence of my attempts at capturing a series of fleeting moments and freezing them in time and on paper. (Rainier is hiding there in the clouds, at the bottom of the above photo—but what I love most is that the cone looks like an erupting volcano! And speaking of which…)

Photo by the U.S. Geological Survey

And then there’s the little corked bottle of volcanic ash on my desk, inscribed with the date of the last major eruption of Mount St. Helens: exactly thirty years ago today.

I’ve been staring at that bottle on and off, all day, reminded of why I’m doing all of this (and why I can’t wait until I have something to show you!).

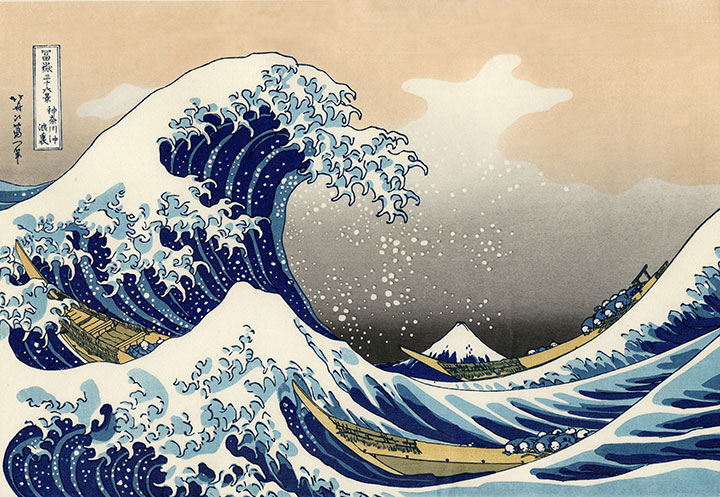

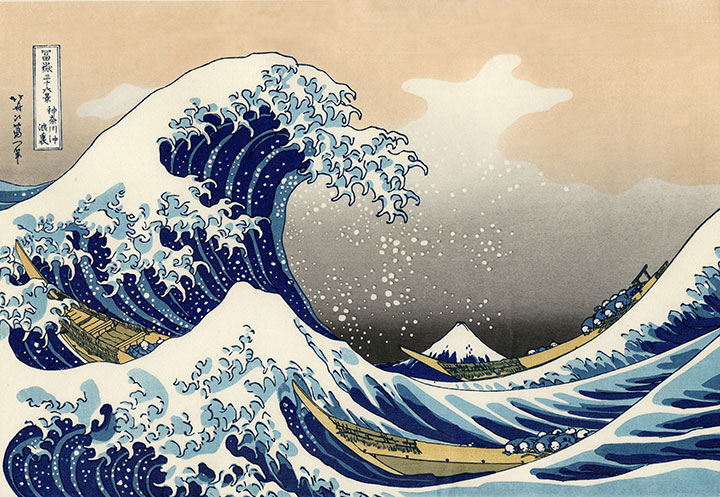

This project began as a tribute to Katsushika Hokusai, the Japanese printmaker and illustrator who created his famous Views of Mount Fuji woodblock series over 150 years ago.

Hokusai wanted to demonstrate the unchanging immortality of Fuji amidst the transient nature of everyday life. To him, Fuji was forever, an unshakable icon of Japan and one of the foundations of his culture.

The trouble is, Fuji is a volcano—just like Rainier and St. Helens—that by its very nature is constantly changing right along with the lives being lived in its shadow. That knowledge is where I found the root of my own project, and since then I’ve tried to document the fire mountain in my own back yard—to be there for every change and permutation.

Today’s date lit a bit of a fire under me, and prompted me to get on with the business of finishing this artist book. Because one day this is all going to happen again. Mount Saint Helens will be first, I’d wager; being the most active and youngest volcano in the Cascades, it may only be a matter of a few years. And some day, even if it’s a hundred or a thousand years from now, Rainier is going to have its turn, too.

For now, though, I’m just doing my best to pay attention to the present moment, because one day I may need help remembering how things used to be.

April 12th, 2010

The sun came out yesterday afternoon, and Mt. Rainier peeked out from behind the clouds. On a whim I tossed my camera into the car and bolted to Paradise, where I had been hoping for one more research shot for my book: Rainier in the snow.

Well, I certainly got my wish.

An hour and a half later I was standing in the cold, at the highest point on the southern park road, and the furthest one can go before the snow melts at the end of June and the rest of the park opens.

I looked over at one of the few cars around me, and was absurdly reminded of all those winters I spent in North Dakota (minus the mountains, of course).

It was nice to think that if I wanted snow, I could come and get it whenever I wanted—without having to shovel my way out of it.

December 10th, 2009

After nearly a year, image-gathering for my Mt. Rainier artist book is finally coming to an end, and I’m starting to make the final illustrations. I have a huge stack of sketches, scribbles and recorded data, and thousands upon thousands of photos to sift through. This month and next are scheduled for the all-important (and terrifying) process of Figuring Out How the Heck to Make It Work—physical mock-ups, final compositions, text-writing, etc. But before I could move on with a clear conscience, I had one last far-away location to cross off my research list: Portland. And for some reason, the stars just weren’t aligning for me.

My first attempt this summer was also my first-ever trip to the city, so I had to location-scout with a blank mental map—and when I finally found what I was looking for, it was too hazy to see anything anyway (hence the dotted line where Rainier should be). Since Portland is 140 miles away, I couldn’t just try again any old time I pleased. As the months went by, I became increasingly frustrated—the location I visited over the summer (Larch Mountain) is inaccessible in the winter, and although I had another spot in mind, my schedule and the weather (which was way harder to pin down than an open travel day!) just couldn’t find anything in common; the last few months have been typically Northwestern, with plenty of rain, fog and drear for a volcano to hide behind. Finally, last week, it seemed I had my chance. T-town was socked in with pea-soup fog, but since the previous day had started the same way and ended in sunshine, I decided to go for it. As I cleared the Puget lowlands and the fog lifted, I caught crystal-clear glimpses of Rainier to the east as I went, and my confidence rose. I wouldn’t know for sure until I got there, but the sunny weather seemed like it would hold. I made good time to Portland, wound my way up to Council Crest Park, jogged up to the viewpoint and faced north—

—and saw that Mt. Saint Helens didn’t get the memo. It had its own private weather system blocking Rainier from view.

It was a long drive home that night.

The last few days were torture. The weekend taunted me with sunny mornings and cloudy afternoons (good thing I didn’t take the bait), and the perfect weather went untested Monday and Tuesday while I taught class and kept appointments instead. By Tuesday night, I was sure I’d missed my last chance, and resigned myself to leaving Portland out of the book. But yesterday dawned cold and flawlessly clear, and I was astonished to find my calendar empty. I left the Tailor an incoherent voicemail at work (“I’m going right now! I’ll be back tonight!”) and jumped in the car. Exactly two hours and twenty-three minutes later, this is what I saw:

That’s St. Helens in front, with Rainier just peeking around her left shoulder.

And here’s the illustration that resulted from all this work:

And in case I had any doubts about one image being worth all this trouble, Portland offered me a little bonus—a compositional jewel that I could never have dreamed up on my own:

The City of Roses was still, impossibly, in bloom.

September 8th, 2009

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m currently in the process of researching Mt. Rainier for my next artist book. This involves drawing and photographing the Mountain over and over (and over and over) again, in as many different conditions and from as many different vantage points as possible. I’ll get into the whys and hows some other time, but for now, suffice to say this is a huge challenge. Not only do we have incredibly unpredictable weather here, but Rainier also tends to play by his own rules, appearing and disappearing regardless of any logical connection to the forecast (which, somewhat ironically, is the entire point of my book…).

I’ve done my best to even the odds by doing the bulk of my research during the summer and early fall—traditionally the dry season here. This summer, however, has proven to be about as nontraditional as possible, and has thrown a whole lot of monkey wrenches into the works. For weeks I had planned a long trip to various points east, where the landscape is drastically different than here in the west. But here’s the rub: not only did I require a flawlessly sunny day to view the Mountain from so far away, but the best time to view Rainier from the east is in the morning—I’d have to leave too early to see that day’s weather report. So I waited, and stalked the National Weather Service, and packed and unpacked my gear. During our ridiculous heatwave we had day after day of beautiful sun, but hot weather makes the atmosphere so hazy that even from here, just forty miles away, Rainier was just a faint silhouette. And then it was one excuse after another; either I had an appointment or deadline I couldn’t change, or it was raining, or it was hot and hazy east of the Cascades, or there was a forest fire blocking my path (no joke!). Over a month went by like this, and I could feel my window of opportunity shrinking—many of the roads included in my plans are closed from October through June.

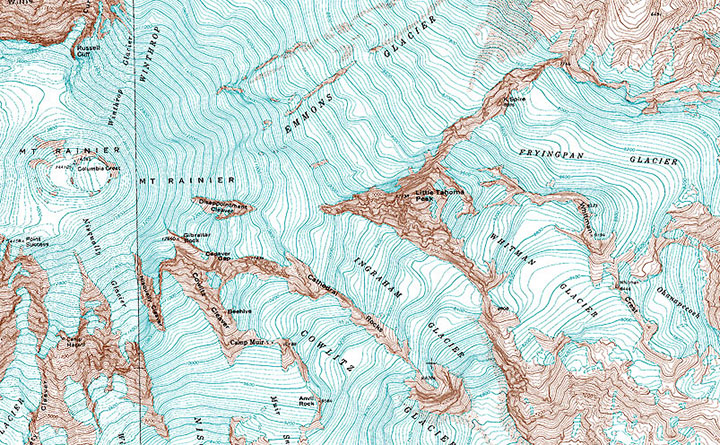

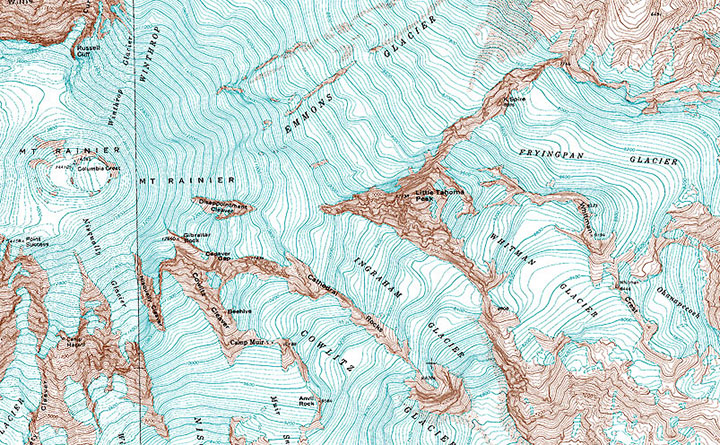

And then, a couple of weeks ago now, it seemed I’d finally get my chance. Every weather report promised dry, cool, sunny weather, for one lovely day, before the gloom closed in again. I packed my drawing paraphernalia, both cold and hot weather gear, a picnic lunch, a pile of atlases and topographic maps (you didn’t think I’d be using GPS, did you? When a letterpress printer marries a geologist, topo maps become a permanent fixture of both studio and science lab!), my camera, and plenty of music in the car, set the alarm for 3:15 am, and went to bed early with my fingers crossed.

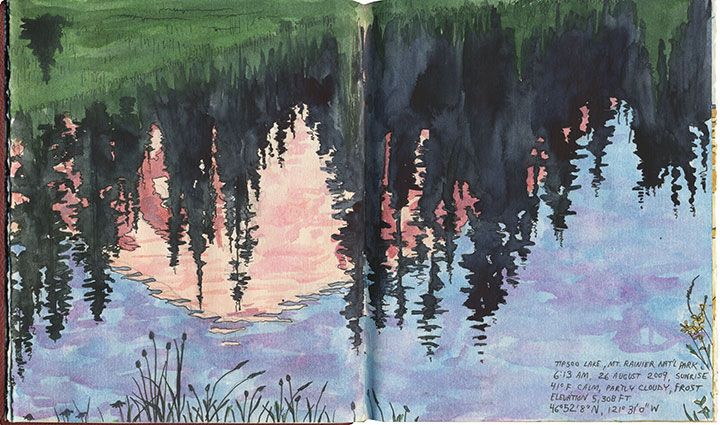

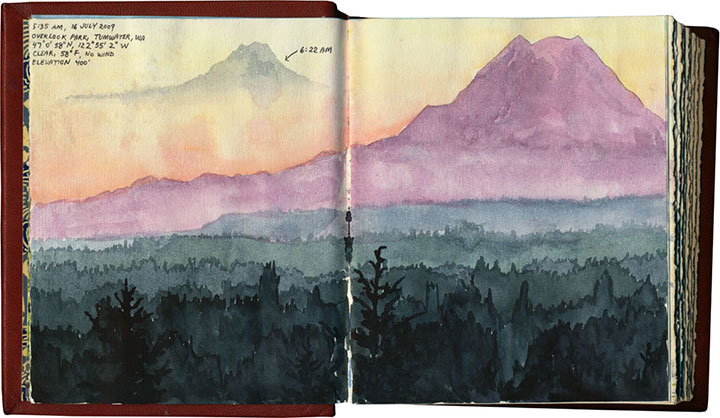

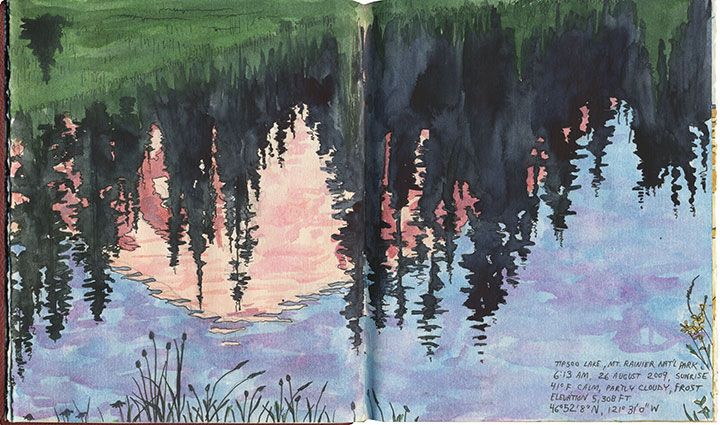

By 3:30 I was ready to go. I poked my head outdoors, saw stars overhead, and decided to make a break for it. Two hours later I arrived at my first stop: Tipsoo Lake, just off the road in an alpine meadow. To my immense surprise I wasn’t alone, even at that absurd pre-dawn, Wednesday hour, with the entire meadow blanketed with frost. A pair of photographers arrived just minutes after me and set up tripods nearby, and a friendly Slovak couple emerged from their tent to introduce themselves while we waited for the sun to rise. The biting cold made me question the sanity of this trip, but when the light finally spilled over the ridge to dye the Mountain pink, all my doubts disappeared.

I stayed just long enough to block in a composition and shoot a few reference photos before the light changed and I lost the moment (I was on a tight timetable all day, so I finished all of these sketches back in the studio). I checked my watch and hit the road again (and waved to the Slovaks as I passed them again, thirty miles later).

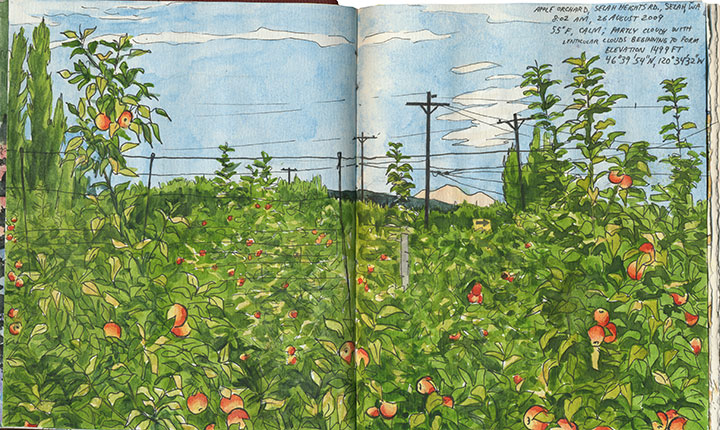

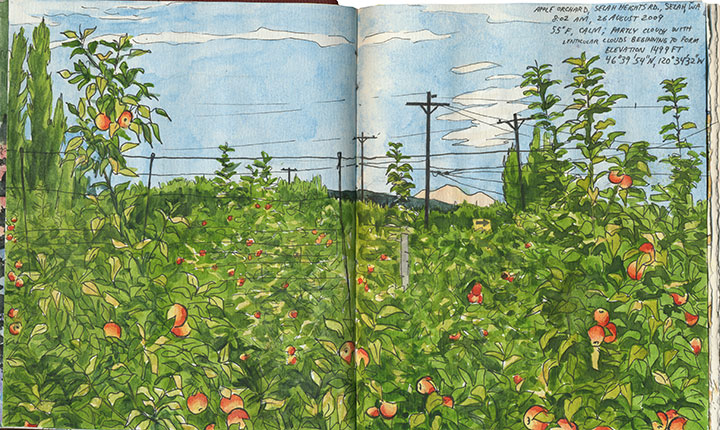

From here onward I had to work entirely on conjecture. Tipsoo Lake is a famous, oft-photographed spot, so I knew what sort of composition I wanted. But I had no photo reference for the rest of my guesses that day, only an idea of what I was looking for and a lot of half-memorized topographic maps. I was hoping to capture a scene of Rainier through the iconic apple orchards of Yakima, but I knew (from all the neck-craning I’ve done on previous drives through the region) that for the most part Rainier isn’t visible from the Yakima Valley, where most of the fruit trees are. According to my maps, though, there were some flat, gridded regions at the top of the bluffs overlooking Yakima—I hoped the grid meant farms, and that the extra 600 feet in elevation would be enough for a glimpse of the Mountain. So I made for Selah Heights Road—a hairline even on my most detailed map.

The road climbed past rows of poplars, trees laden with fruit and sweeping views of the valley; so far, so good.

And then I found it: just the tip of Mt. Rainier visible between the apple trees. I couldn’t believe my luck. And just as I finished roughing out my drawing (I still had a lot of miles to cover before my next destination, so I worked fast and loose), I glanced to my left and discovered another treat:

Mt. Adams, for a little extra credit.

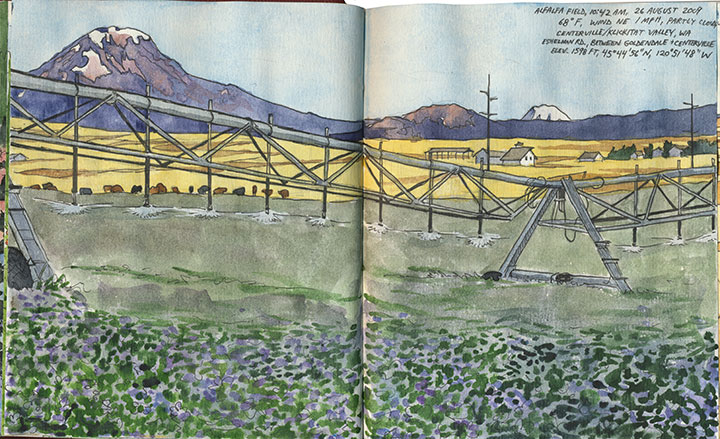

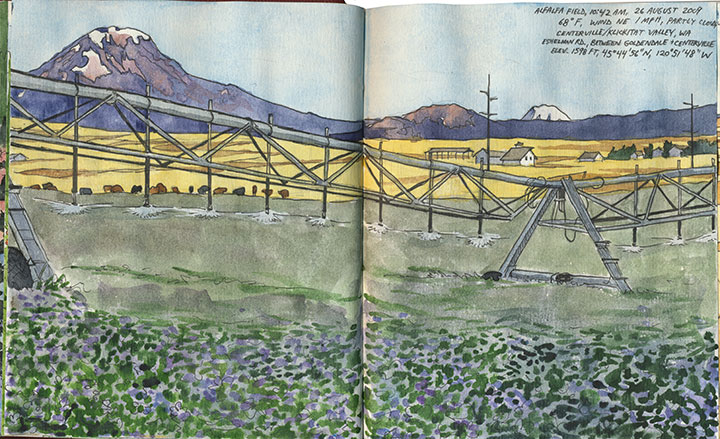

After a quick, desperate and delicious coffee in Yakima, I turned south. My next stop was a place I’d never been: the Centerville Valley, a high-plains agricultural area just beyond Goldendale.

I knew that Adams would be prominently visible from here, but I could only hope that Rainier was as well—it sure would make a pretty picture if it were, I thought.

Nope, still Adams—although from this angle it tends to fool people (and cows).

I looked behind me, and saw that the farmland sloped upward a bit, before giving way to the Columbia Hills. So I headed south along a dirt road for about a half mile, parked, and trudged a few yards into a field of wheat stubble.

Bingo.

The alfalfa blossoms were sheer luck, just like so many other things that day. And that irrigation rig was moving—so I was never more thankful for digital photo technology than that moment (as a die-hard darkroom enthusiast, I never though I’d say that!).

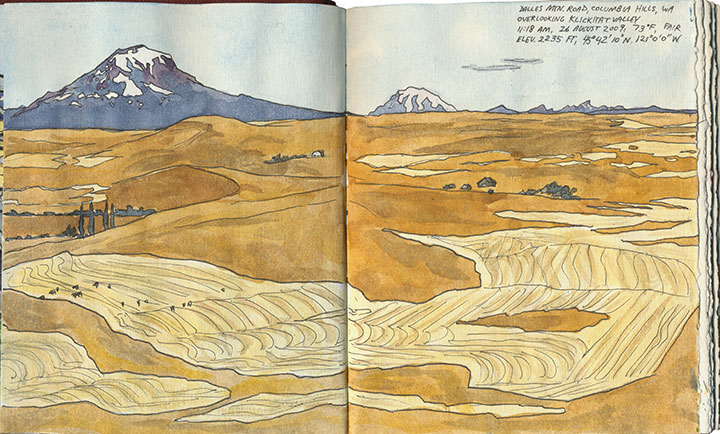

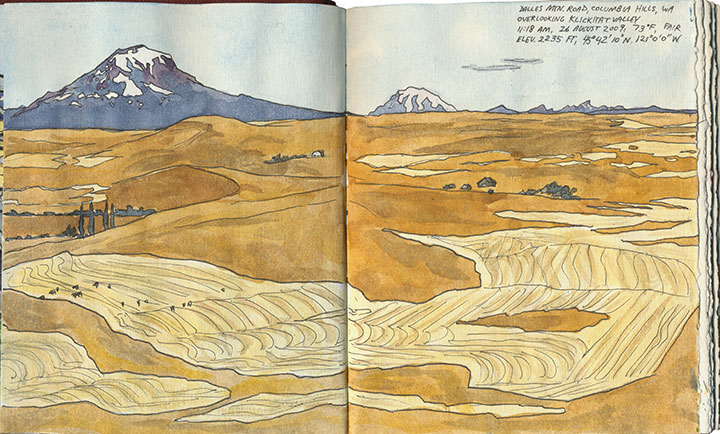

Only one item remained on the itinerary: a narrow, winding goat track called the Dalles Mountain Road.

The spectacular vista of Adams, Rainier and the valley was just the beginning.

The road snakes over the top of the Columbia Hills, providing views of five volcanoes (that’s Hood there)…

pockets of stunning wildflowers…

and plenty of road-side snacks.

On the southern slope of the Hills the landscape turns suddenly rocky,

and the mighty Columbia River bursts into view.

My research had gone off without a hitch, and right on schedule. It was only just noon: mission accomplished. So to celebrate I stopped for lunch at one of the most stunning picnic spots I’ve ever seen.

From that little patch of grass I could have chosen to go home the way I came, or finish the loop and return along the western side of the Cascades—it was almost perfectly equidistant. So as usual I chose the unknown road, and zipped home via the historic Columbia River Highway.

Fifteen hours, 515 miles roundtrip. And perfect conditions every step of the way. I think that after a summer of total frustration (remember the airplane incident?), maybe the universe decided to give me a break.

I’ll be sure to send a thank-you note.

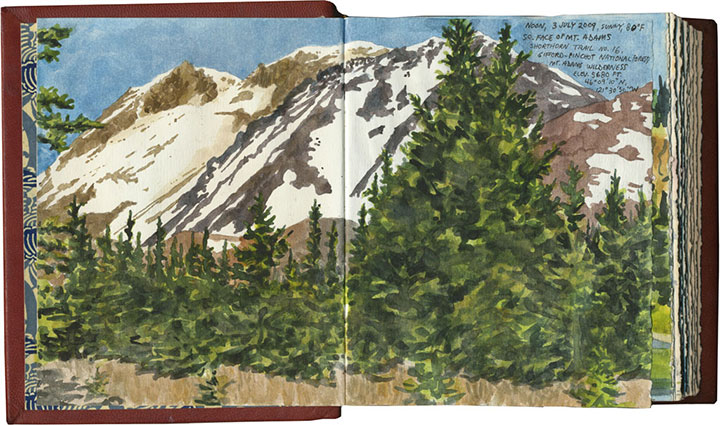

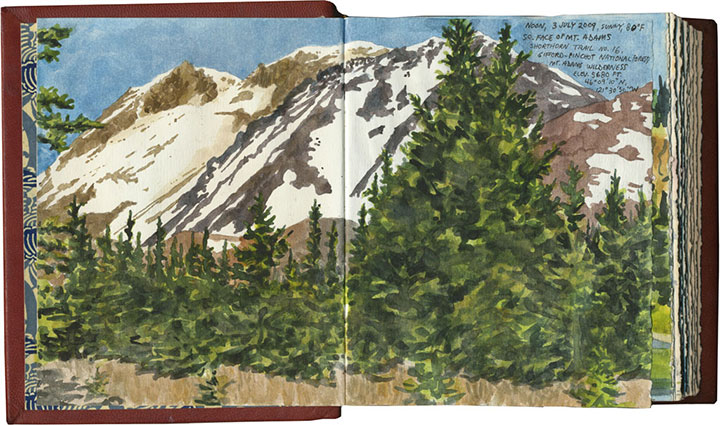

July 6th, 2009

In my (so far) limited experience, Washingtonians tend to be outdoor types—and with good reason. With so much beauty at our fingertips, it’s no wonder that with the first hint of a sunny day, we’re out in force. Add to that the near-clockwork arrival of the dry season by Independence Day, and the fact that huge swaths of the mountains are inaccessible for nine months out of the year—well, you can see where I’m going with this. Since the Fourth of July was kind enough to fall on a Saturday this year, the cities emptied and thousands headed Outward. And this year, though we’re normally Off-Season, Off-the-Beaten-Path types, the Tailor and I were no exception. Like zombies we staggered outdoors to pack our tiny Subaru sedan—must … go … camping!

We knew it was probably folly, but we had a goal in mind: find a beautiful, mountainous campsite away from the teeming hordes. We knew Mount Rainier would be out of the question, as were the Olympic Peninsula, Mount St. Helens, or any other popular tourist destinations—but even though we had a head start by leaving on Thursday afternoon, our hope faded as we saw the crush of fellow vacationers on the freeway. “Camper … camper … RV … canoe … RV … kayaks … cyclists … camper,” the Tailor droned, counting cars, “this was a dumb idea.” Yet as our route took us on smaller and smaller roads, the number of fellow travelers dwindled almost to none. It began to seem like our instincts were right after all.

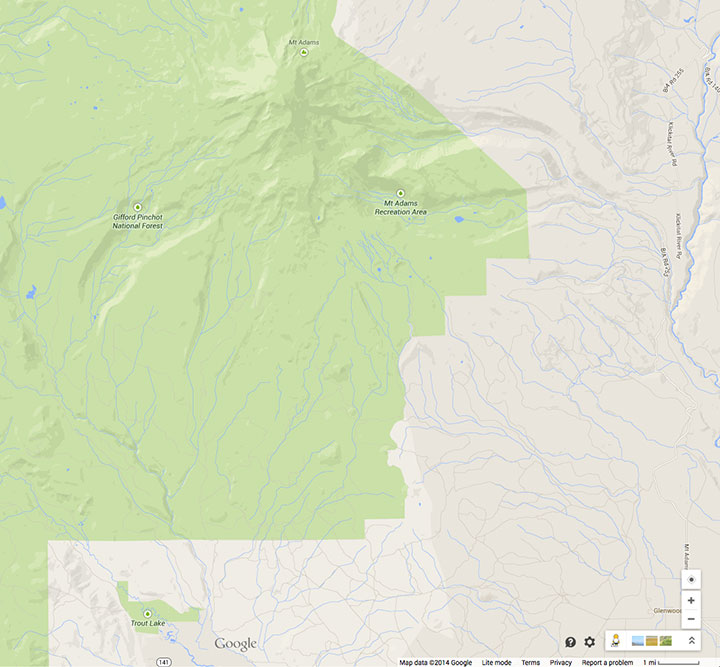

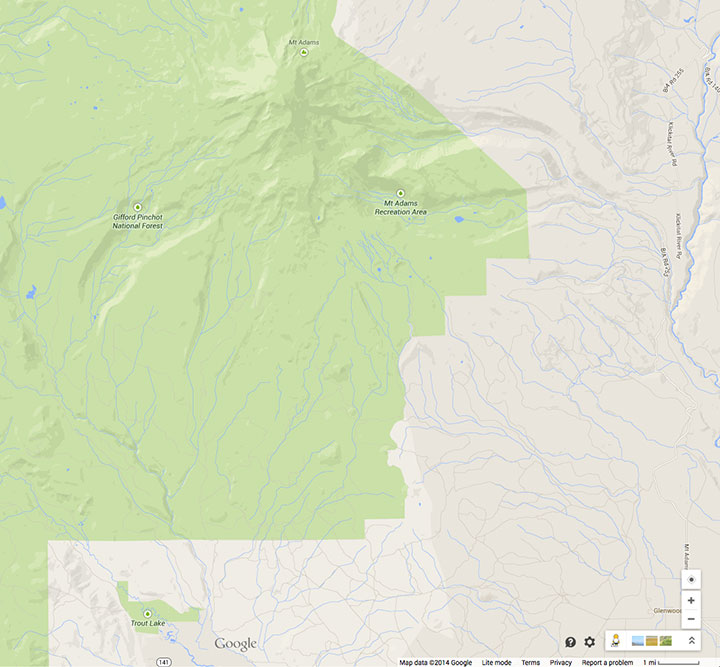

Our destination? The Morrison Creek Campground, located on the southern slope of Mount Adams, Rainier’s slightly-smaller, lesser-known brother.

While we were nervous of the possibility of any volcano attracting busloads of holiday tourists, our choice had a couple of points in our favor. For one thing, one can’t reserve a campsite in a national forest; all sites are taken on a first-come, first-served basis. For another, Morrison Creek is in the middle of freakin’ nowhere.

The only way to get there from the north is to use the system of Forest Service roads that wind through the Gifford-Pinchot National Forest. The paved sections are breathtakingly beautiful and super fun to drive (especially with a stick shift; I felt like I was filming a car commercial). The “unimproved” stretches, on the other hand, range from challenging to terrifying. Mindful of the consequences of puncturing an oil pan or snapping an axle on a holiday weekend in one of the most remote pockets of the state, I took my sweet time picking my way around the detritus of recent rock slides and dodging monstrous potholes.

When we pitched our tent just as the last light faded, however, we knew that it was absolutely worth the trip. Our campsite was in a lovely, secluded spot, adjacent to the Creek, just below the last traces of mountain snow, and surrounded by pockets of blooming beargrass. And to our immense surprise, we had Adams almost entirely to ourselves, for the whole weekend—funny, considering that the next campground, three miles up the road, was crawling with mountain climbers.

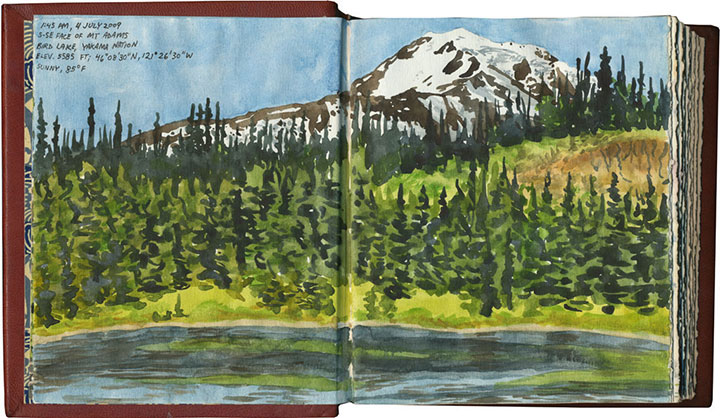

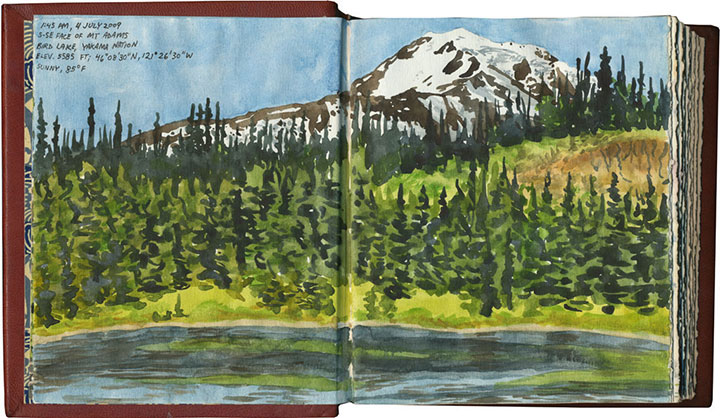

I was hoping our travels would afford us at least one view of Rainier in the distance—that way I’d have another sketch to add to my store of potential artist book imagery. FS Route 23, however, doesn’t afford such a vista, and any potential viewpoint reached by hiking trail was well out of range of our abilities. A two-mile hike from our tent did give us a spectacular, alpine-meadow view of Adams, though—and I realized that for my research purposes, I could use the peak as a sort of stunt double.

From certain angles, Adams is remarkably similar to Rainier (and people often mistake one for the another when viewed from a distance). All the more reason to use my time there for drawing. I was surprised to see, however, how drastically Adams’ appearance changed, depending on the vantage point. This is the view from Bird Lake, on Yakama Nation land, just a couple of miles (as the crow flies) east of Morrison Creek:

And though there was nowhere to sit to capture it in my sketchbook, a gap in the trees gave me the chance to glimpse another stand-in to the south: Mount Hood.

What an incredible weekend. As you can probably guess, Adams is on the short list for Best Camping Spots Ever, and I’m sure we’ll end up returning again and again. Next time, though, it might behoove us to reconsider our mode of transportation; it’s doable in a compact car (just barely), but I think I’d rather rent a pickup truck—or a mountain goat.

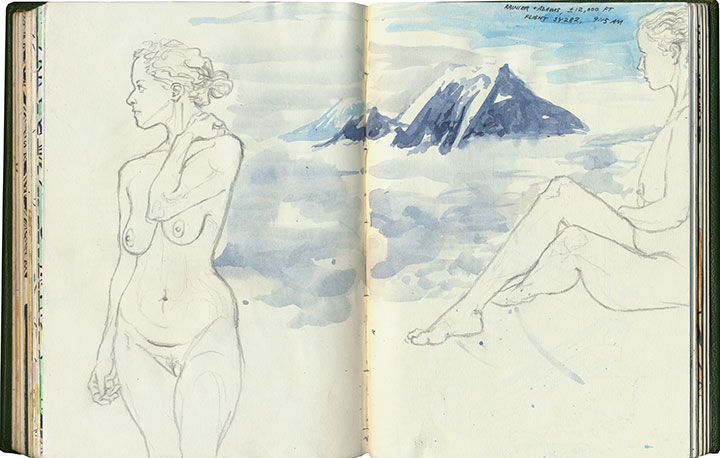

June 30th, 2009

A few months ago I was granted funding by the City of Tacoma Arts Commission to create my next artist book edition. Since this is the first of what will probably be a long string of posts over the next eighteen months, I’ll save the details for later. For now, I’ll just say that the book deals with the changing appearance (and intrinsic nature, since it’s an active volcano) of Mt. Rainier. At the moment I’m knee-deep in research, trying to capture the Mountain in as many different—well, attitudes, as Jane Austen would put it—as possible.

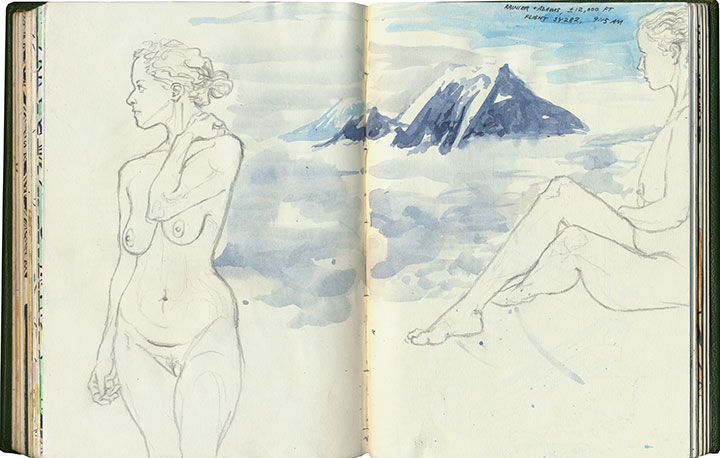

The Tailor and I spent last week visiting old friends and haunts in Minneapolis, and as luck would have it, I had the window seat on the south side of the plane on our flight out. I had my paints, brush, and film canister full of water ready as we taxied, so that when we cleared the cloud ceiling I had a solid two minutes or so for a sketchbook snapshot.

It occurred to me, though, that while a 120-second gesture painting (complete with frantic paint spatter) would be a nice addition to the sketchbook, it wouldn’t provide nearly enough reliable detail to serve as the basis for a future letterpress print. So on the way back, I requested another window seat (I think the fact that I’d sprained my ankle on our last day of the trip, and had to hobble to the counter, might have helped my case a bit) so as to document any Mountain sightings with the camera.

The counter attendant had been kind enough to place me on the correct side of the plane again. And the weather was crystal-clear, affording the passengers with stunning, morning-lit views of Rainier and the entire Cascade volcano chain. The cabin was filled with sounds of hushed awe and clicking shutters. There was only one snag in my research scheme—Row Nine, in which we were seated, seemed to use the term “window seat” loosely.

And the universe kept right on laughing.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)