Blog

August 25th, 2016

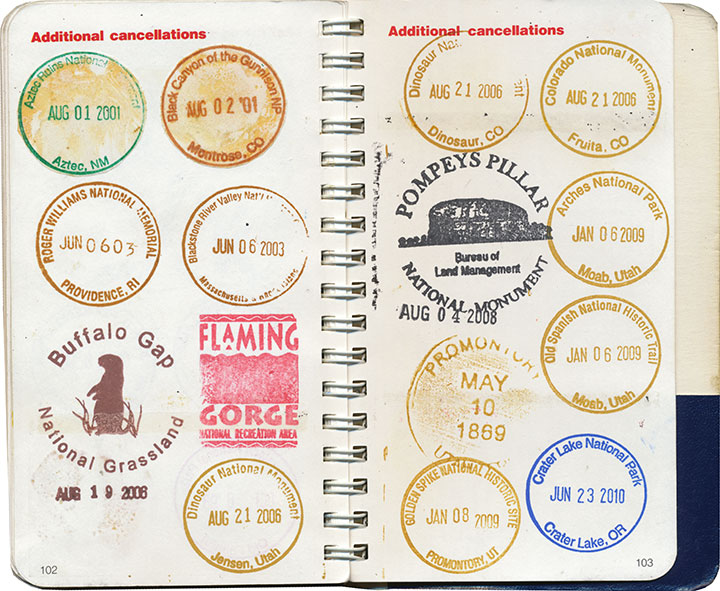

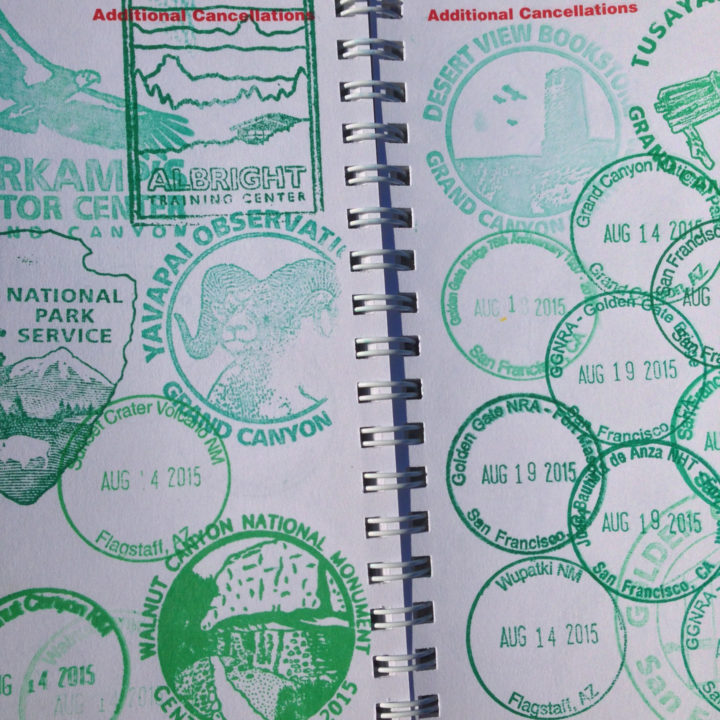

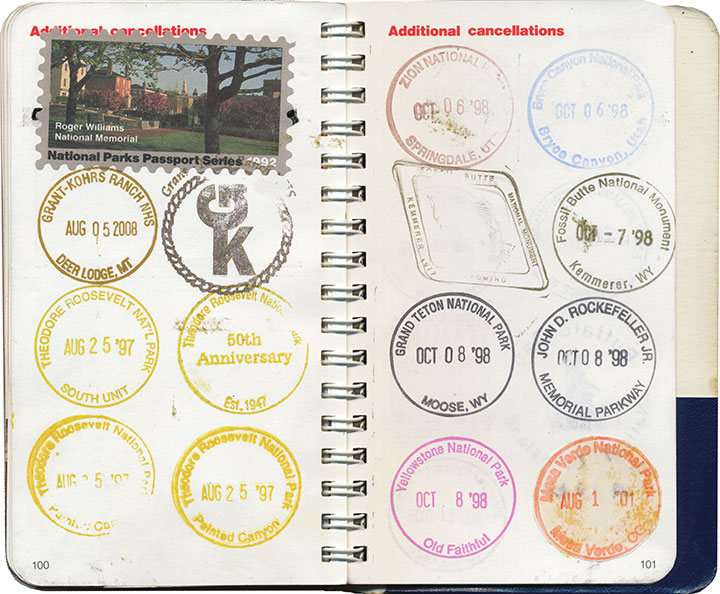

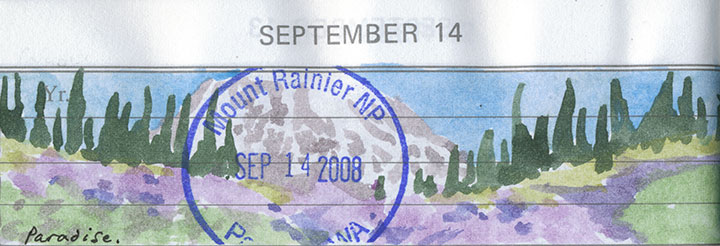

I don’t know about you, but on this, the National Park Service centennial, this millennial is paging through her big fat stack of stamped pages, proof of a lifetime of national parks love. Apparently I like to cram that ink into every nook and cranny of my passport—but that’s good, because I’m trying to leave room for many more to come. Happy 100th birthday, NPS—here’s to many more!

June 19th, 2011

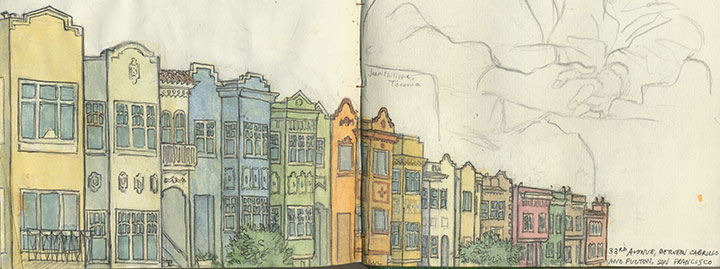

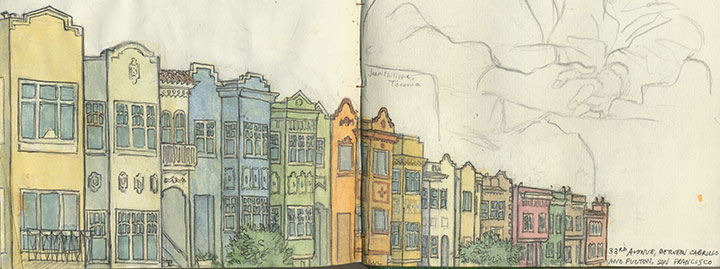

Even though my trip south originally brought me across the Bay, it seemed like San Francisco was the logical starting point for my long trek home along the coast.

So after a quick sketch (while humming that Journey song that popped into my head for the umpteenth time), I crossed the bridge and headed north.

It wasn’t long before I’d left civilization almost completely behind. My chosen route was the (in)famous Highway One, which winds a precarious path along the shore, with breathtaking views and treacherous challenges at every hairpin turn. In other words, it was perfect in nearly every way. Despite the environmental guilt of it all, I confess that I love driving—and hugging the curves of 300 miles of switchbacks in a stick-shift Subaru? Pure, unadulterated bliss. And while I missed the company of the Tailor, or any of my other traditional travel buddies, it was nice to be able to stop and take a picture every thirty seconds, without the risk of annoying anyone!

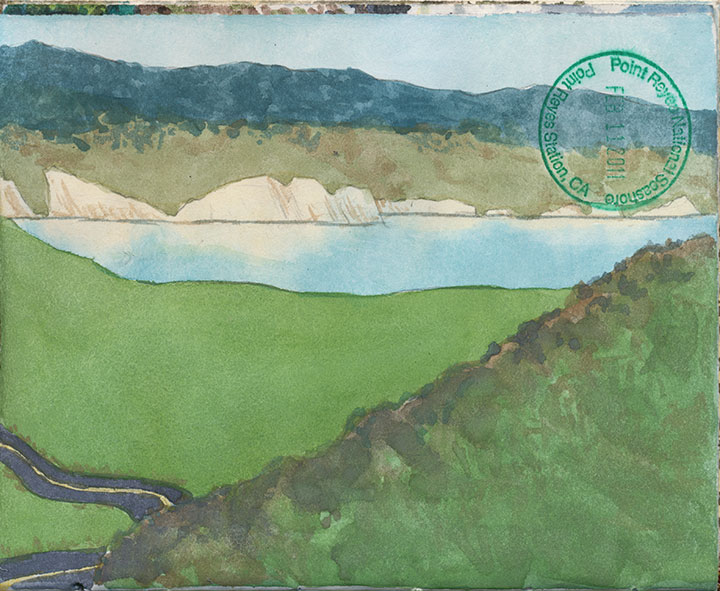

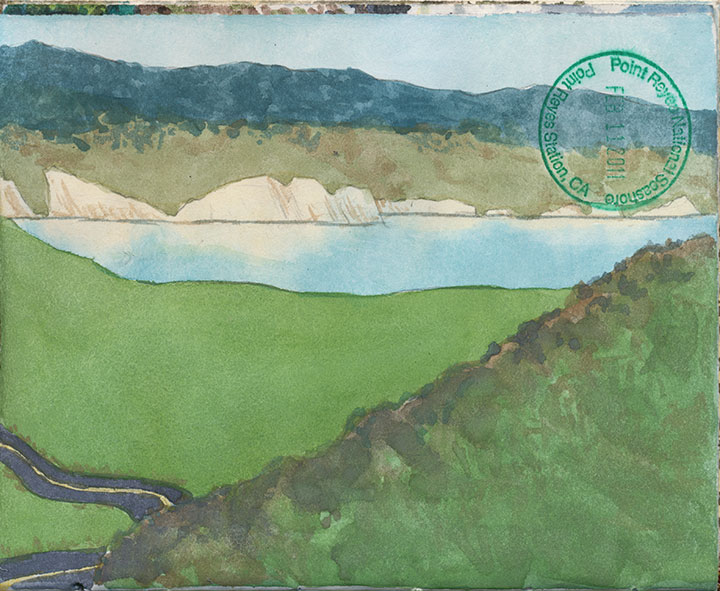

I knew that by traveling the Coast Highway on a weekday in February, I’d have the place pretty much to myself. But I was completely unprepared for the solitude that awaited me at my first stop along the way: Point Reyes National Seashore.

Point Reyes is a long, jagged cape with an equally long history. Sir Francis Drake reportedly landed there in 1579, and people have inhabited it, farmed it, settled it, and even wrecked their ships upon it for many, many generations. Since the 1850s much of the land has been parceled out into dairy farms, which are still in operation today, thanks to the protection of the National Park Service.

What first struck me about the place is the near total absence of trees. The place reminded me more of the Scottish highlands than anything I’d seen in California—and in fact, one of the few small towns located on the peninsula is called Inverness.

And I’m sure that at the height of summer, the place is crawling with tourists—but that day I was completely alone. For miles and miles and miles, it was just me and the cows.

I hadn’t intended to travel the whole length of the cape; I wasn’t on a fixed timetable or anything, but by that point it was already late morning. But I saw a sign indicating a lighthouse ahead, so I kept going. There was no mile count on the sign, and I didn’t bother to fish out the map. It couldn’t be far, right? Well, the road wound on and on and on, with no sign of a lighthouse, and no indication of where this would end. But then, a full twenty miles on, the track came to an abrupt end. I got out of the car, faced back north, and nearly had to pick my jaw up off the ground.

The lighthouse was just a short hike from there:

I could see why people were forever dashing their boats upon the rocks.

And that wasn’t the only thing I could see. I was staring into the bright teal surf when something surfaced and caught my eye:

A gray whale! It’s funny—I’ve lived on one coast or another for over eleven years of my life, and I’d never seen a whale in person before. If that wasn’t worth the forty-mile detour, I don’t know what is.

After the whale-watching and a 2-minute watercolor, I made the long trek back to the highway.

The remaining stretch of Highway One was almost equally deserted. It made the miles melt away quickly, and gave me the feeling that I had the whole Pacific to myself.

Before long, the rolling hills and eucalyptus trees tapered off,

and the landscape gave way to cypress stands and evergreen forests.

The road ended just as the day did. As the sun went down the path turned eastward, away from the shore, and plunged into the thick darkness of coastal forest. By the time I pulled into a hotel for the night, it was pitch black, and Highway One had been replaced by the other Pacific Highway: US 101. I was in completely unfamiliar territory, and would be until I came all the way north to Astoria several days later, but despite the darkness and lack of bearings, I knew what lay ahead. And I was almost too excited to sleep, because I knew that in the morning, the sun would reveal exactly where I was: in the heart of redwood country.

August 21st, 2010

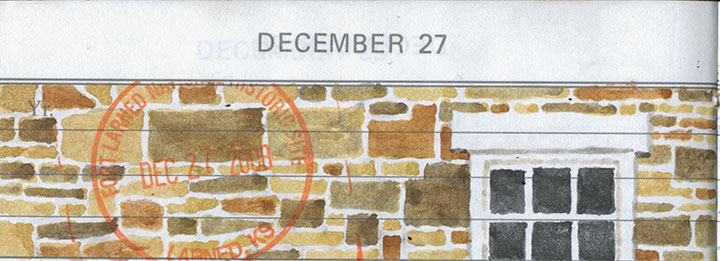

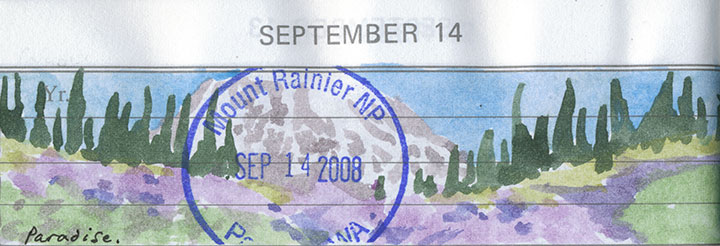

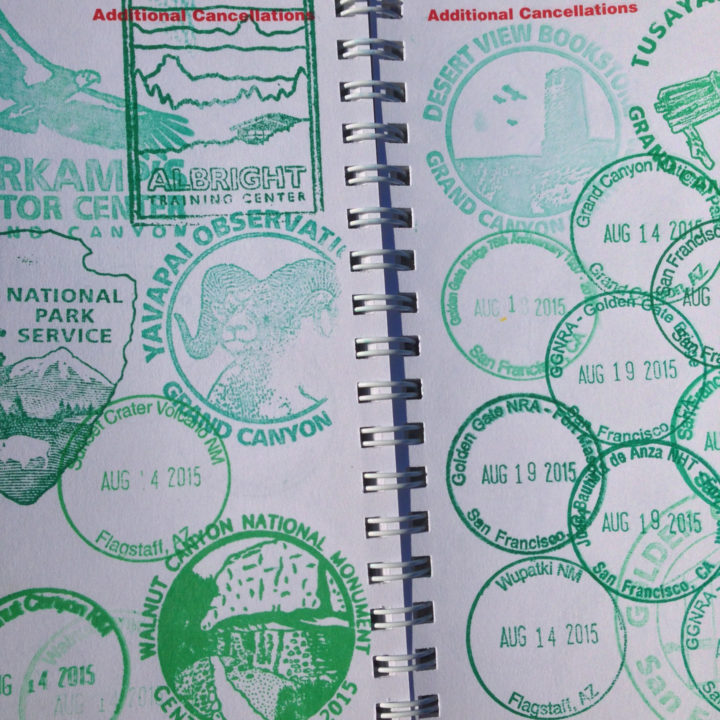

Since I posted this drawing and some others this summer, people have been asking me what’s with the stamps in my sketchbook. I guess the short answer is that each one is a little piece of personal tradition.

But you know I don’t really do short answers.

The long one, then.

I grew up in a nomadic family. Between the moves required by Dad’s job in the Air Force and a fierce wanderlust that runs in all the O’Leary veins, we had a lot of reasons to travel. Dad and I, especially, would spend hours poring over our dog-eared Rand McNally road atlas, plotting routes over the back-est of back roads (the squigglier the line on the map, the better) and stops at as many points of interests as we could cram into a journey from A to B.

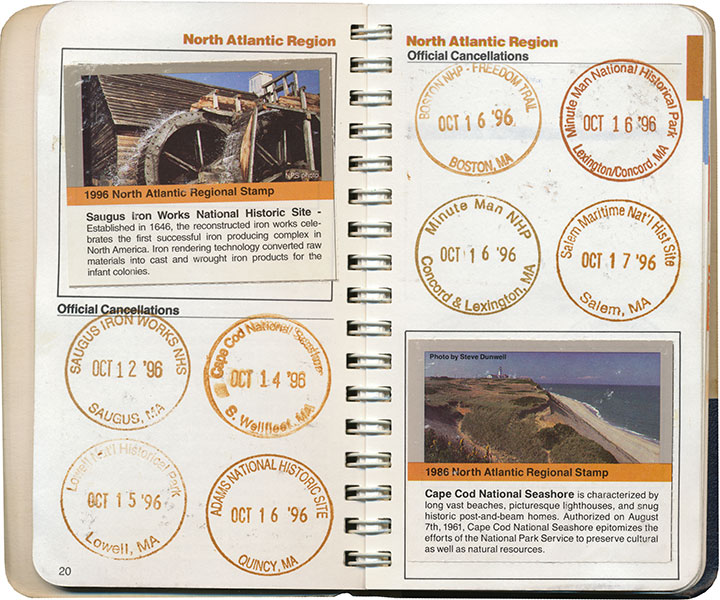

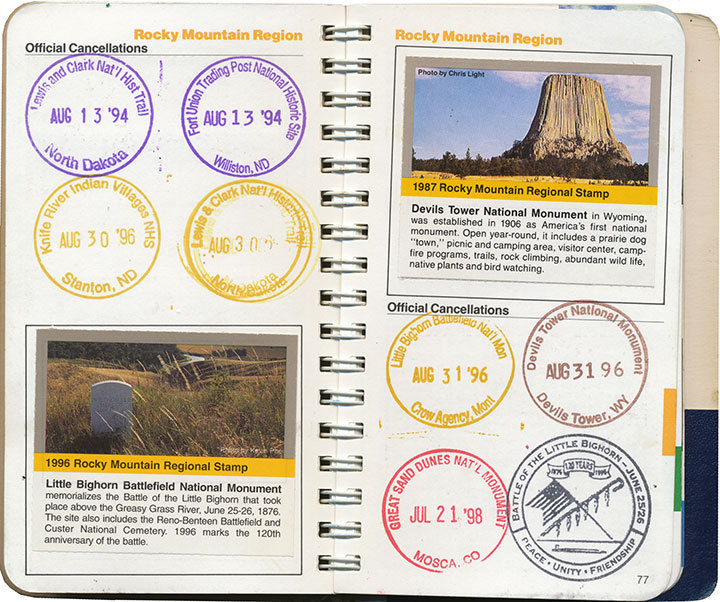

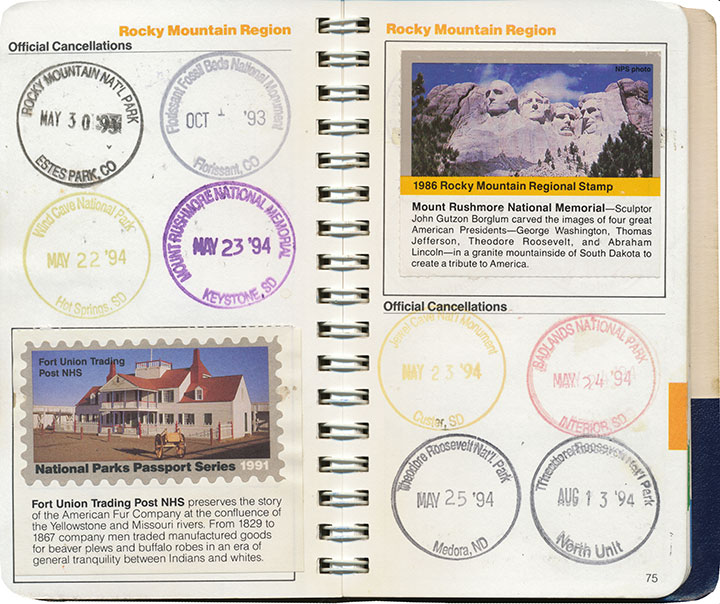

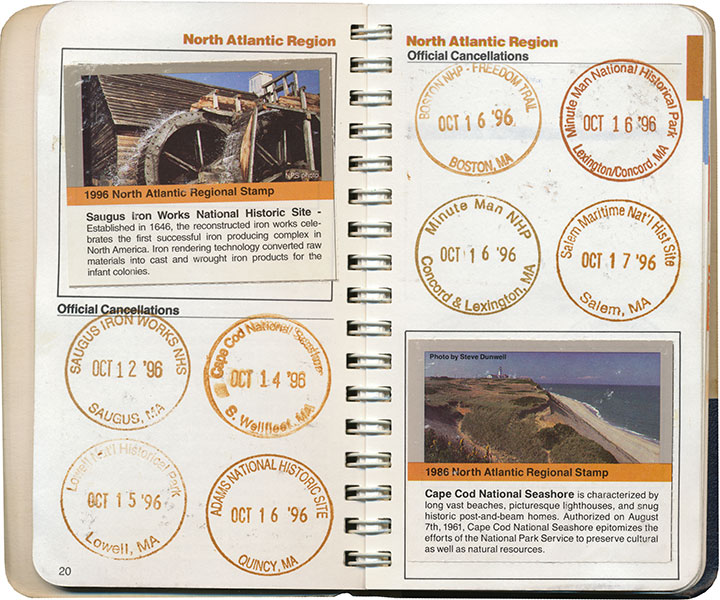

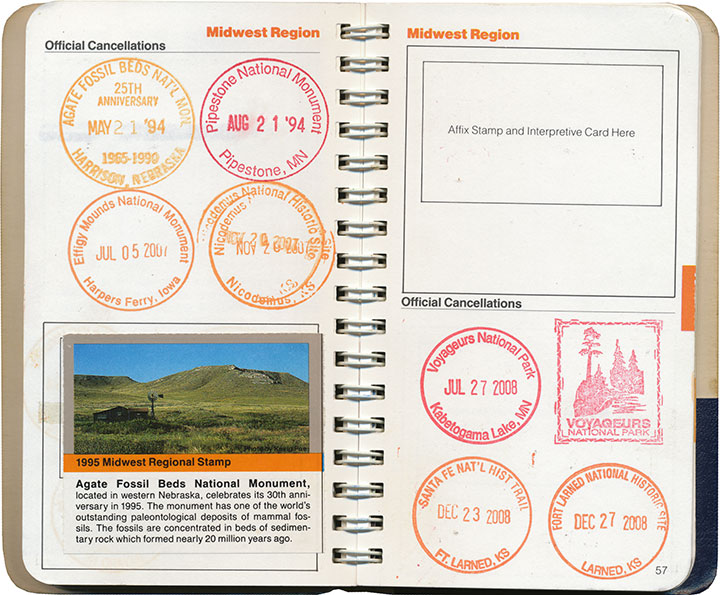

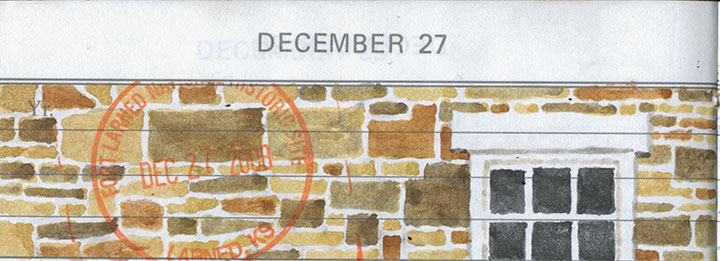

When I was ten, we made a circuit of our then-home state of Colorado, and devoted our time to exploring every national park and monument we could reach along the loop. At each park’s visitor center, we noticed a rubber stamp and ink pad stationed at the front desk. When we finally asked a ranger what they were for, she handed us a small blue notebook and proceeded to explain about the National Park Service’s Passport program.

A stamp to collect at every NPS property in the country, and a tidy little book to hold them all? I was hooked.

Dad and I found ways to sneak a national monument or two into every road trip and relocation—and even took impromptu vacations just to add a new park to the list. My favorite memory is when I was in high school, and Dad popped his head into my room:

“Have any plans this weekend?”

“Uh, no…”

“Wanna go to Montana?”

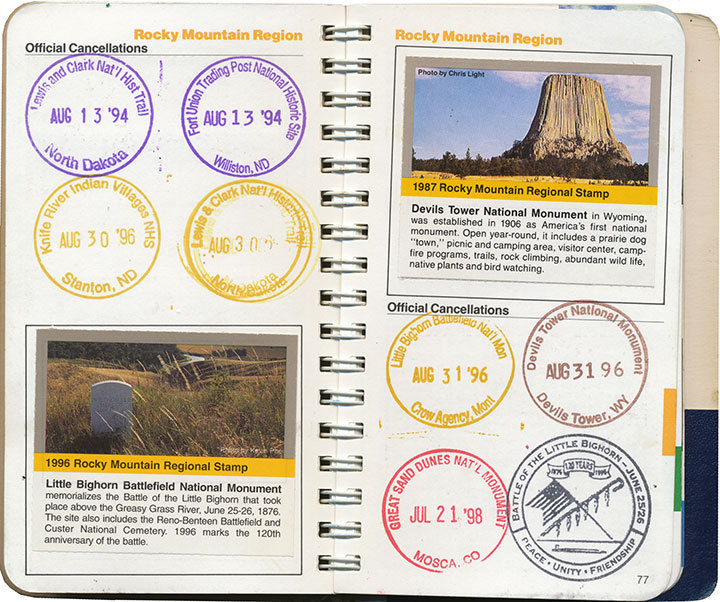

So we jumped in the car and drove 600 miles just to flip General Custer the bird at Little Bighorn (I had just read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, so he wasn’t exactly stirring me to patriotism). I mean, if you’re going to do it, you might as well go all out, after all. And we had the stamp to commemorate the moment.

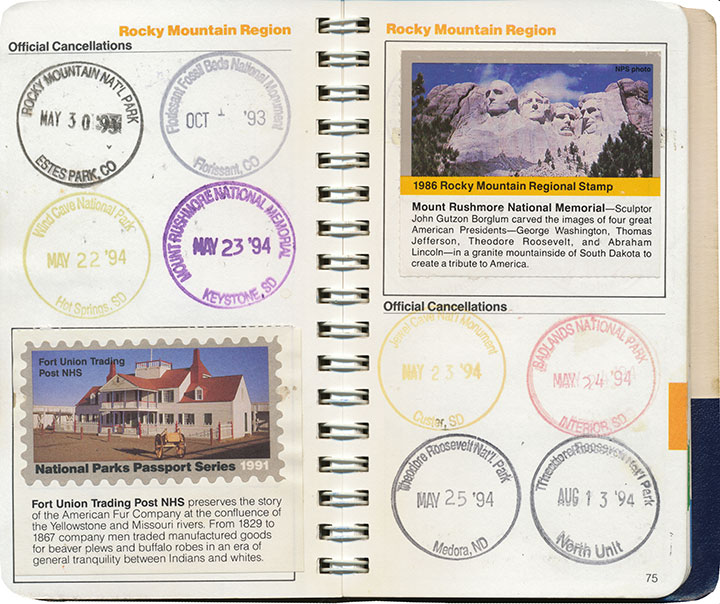

The Passport program also includes collectible paper stamps, which can be purchased from afar (as opposed to the ink cancellations, which are free but can only be obtained in person). I’m pretty lukewarm about these, though; by the time I jumped on the bandwagon they had already phased out the super-cool two-piece design pictured in the lower left corner above, in favor of the cheaper, lower-quality one-piece stamp in the upper right. Since those have been revamped yet again into a pressure-adhesive sticker—and who knows what heinously non-archival chemicals might be in the glue—I’m even less of a completist about them now.

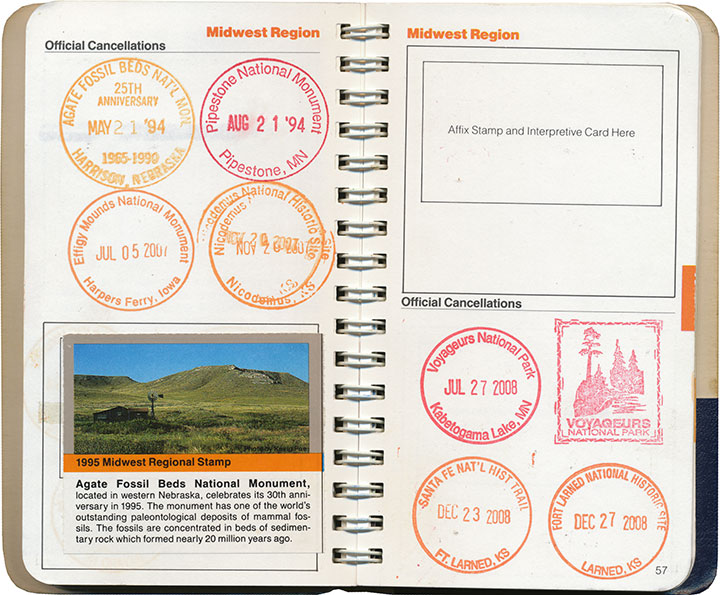

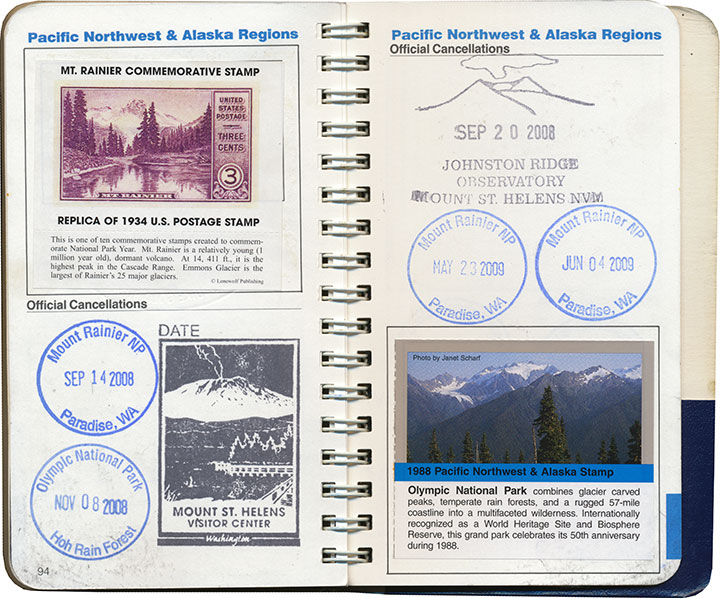

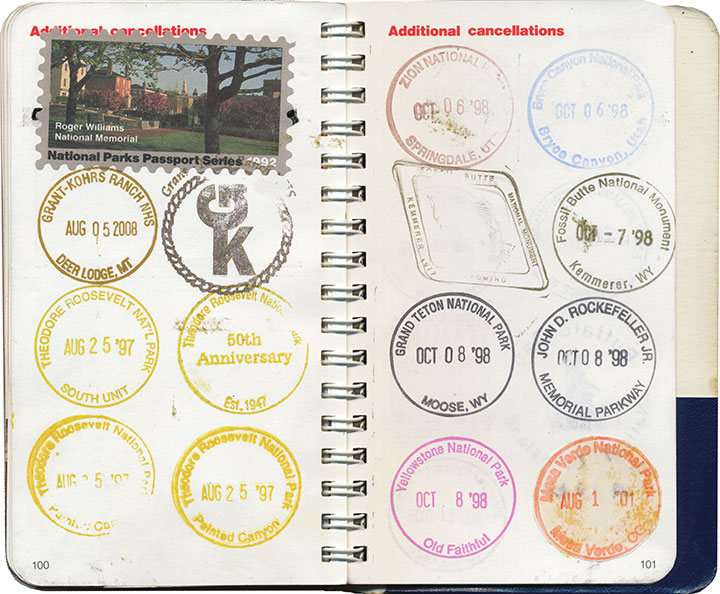

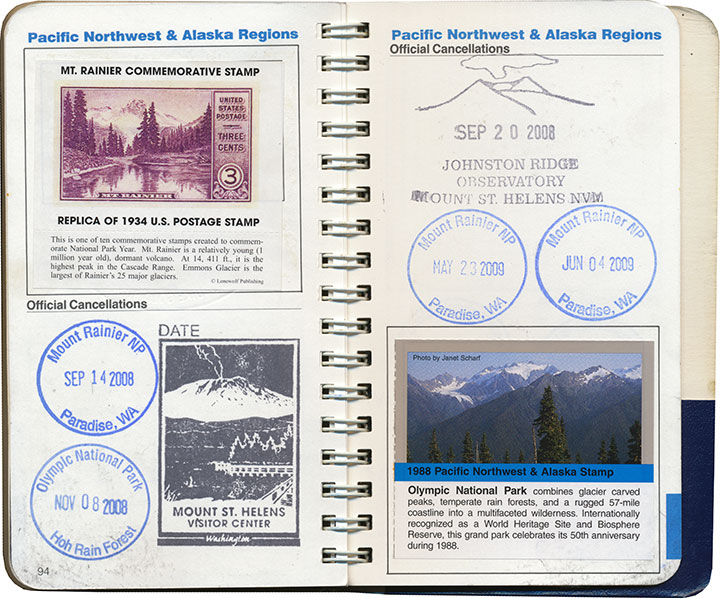

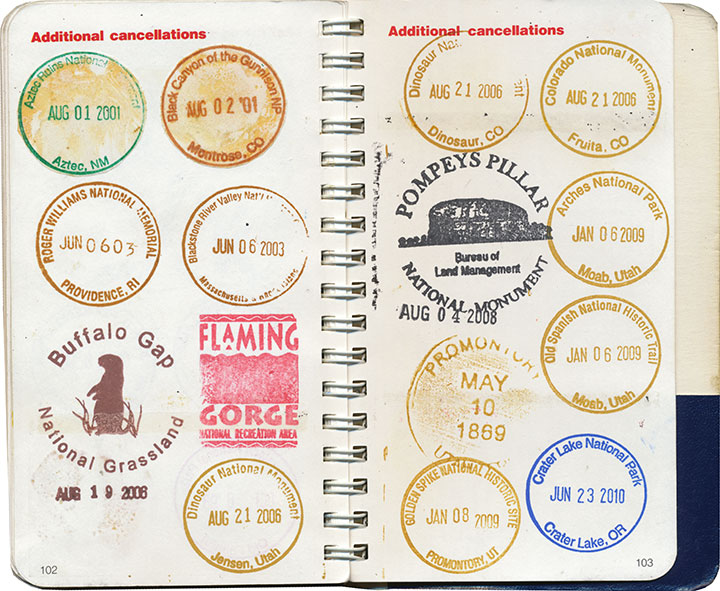

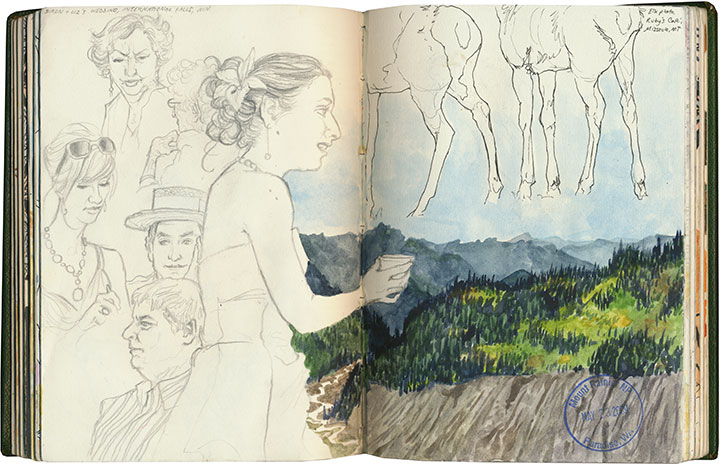

Anyway, I’ve burned through most of the regional sections in my Passport,

and every inch of overflow space.

So I’ve branched out a bit.

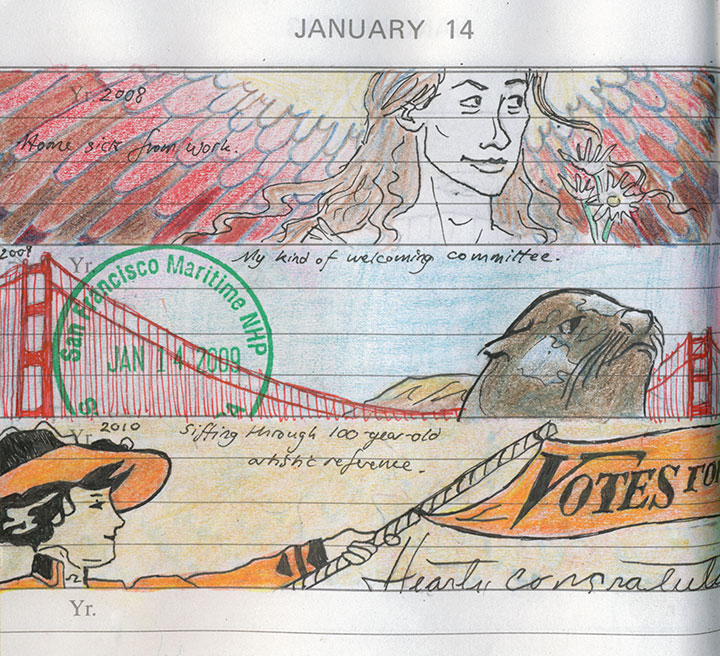

What I didn’t know as a kid was that my Passport helped me develop my interest in nearly everything I love most: traveling, design, archiving, printmaking, history, typography, bookmaking, and so on.

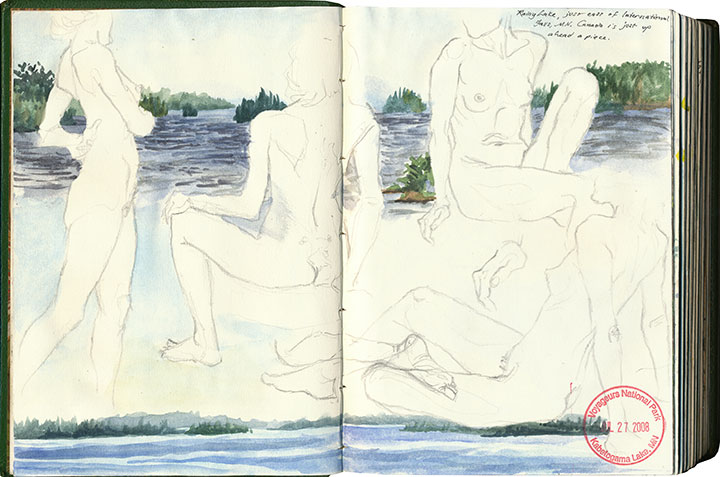

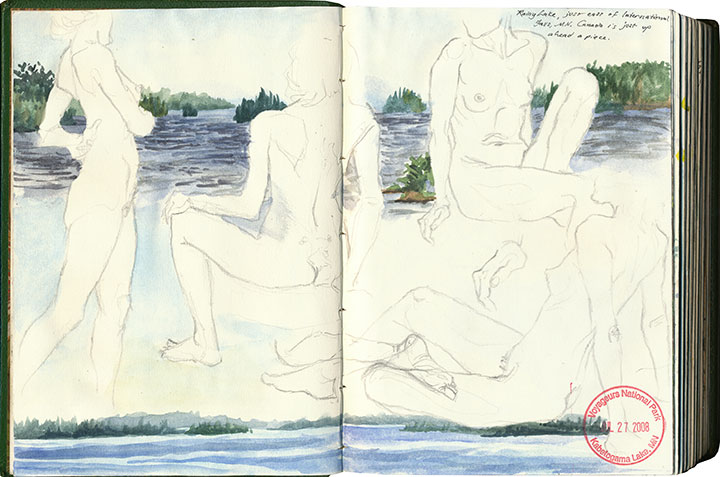

At some point along the way, I realized that what I really mattered to me (beyond the travel itself) was the act of adding to an ongoing work—and then looking back to see what I had accomplished. That what I had been doing all along, by compiling this little individual history, is creating some form of artist book. And that my frustrations over an imperfect format were really a desire to create my own.

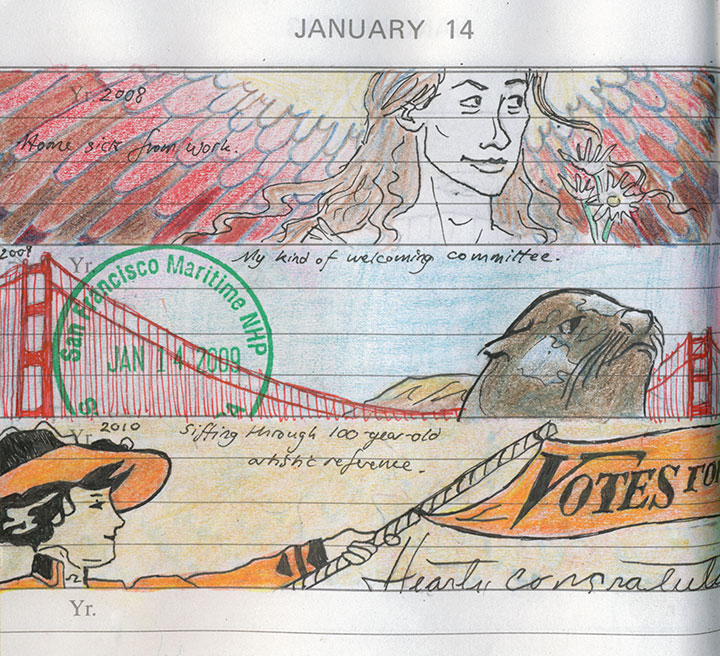

A page from my daily book—more on that here.

So now all of my sketchbooks are Passports, each custom-tailored—

each infinitely flexible, ready for whatever adventures wait to be documented.

Here it is, nearly twenty years later, and I’m as eager as ever. Moreover, it’s my goal to collect every last cancellation within the entire National Park System before I stamp the big passport book in the sky. I’m about a quarter of the way there.

And I’ll probably have to build a library for all the sketchbooks I’ll fill between now and then.

Save

July 17th, 2010

The second part of my little stolen holiday was a little more ambitious: a four-night camping trip with the Tailor in southern Oregon. It was just what the doctor ordered—the perfect prescription for recharging the soul.

We camped in the Rogue River National Forest, in a grove of hemlocks and blooming dogwoods, just downstream from this:

The Rogue is so beautiful that we could have spent the whole trip exploring its banks. Well, if we hadn’t had another destination in mind, that is:

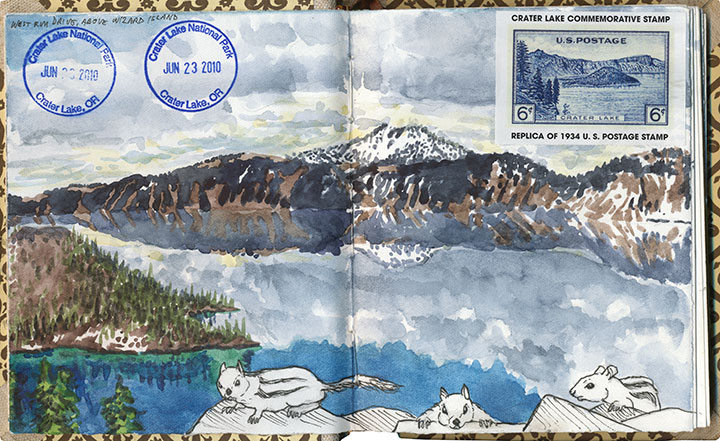

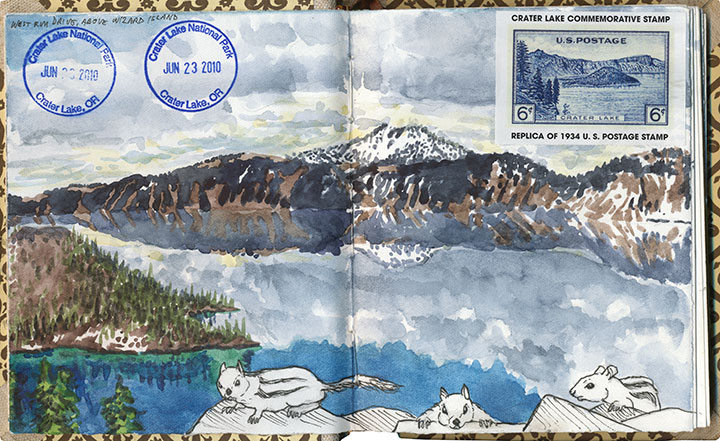

Crater Lake National Park. One of the deepest, clearest lakes in the world, Crater Lake was formed 7,700 years ago by the collapse of Mt. Mazama, after an explosion more than forty times the size of the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens.

When a group of prospectors stumbled upon it in 1853, and thus became the first white folks to lay eyes on it, they named it Deep Blue Lake. Heh. You can tell they worked hard to come up with that one. Well, at least it’s descriptive.

And accurate. The lake is so impossibly blue because of its depth; when the sun’s rays refract upon hitting the water, red and green light are absorbed in the depths, while only the blue light (which has a shorter wavelength) reflects back to the surface. So the lake is blue even on a cloudy day—as you can see.

We were a week too early for the boat tours to open for the season, but we hiked down to the water anyway. The rangers like to say that the trail is “one mile down, ten miles back up” (it’s funny because it’s true. Oy.), but the experience is well worth the huffing and puffing. Next time I’ll bring bug spray, though. Note to self.

Did I mention that it’s blue? And deep? Maybe those prospectors were onto something.

The photo above doesn’t come close to doing it justice (none of my photos do), but the sheer depth and clarity of Crater Lake was mind-boggling. It’s impossible to tell how deep the rocks in the upper left corner of the photo are, but according to the topo map in front of me, it’s quite a ways down. Because there are no streams in or out of Crater Lake, there’s nothing to muddy or disturb the water—objects are visible nearly 150 feet down. Deep Blue indeed.

The thing that really got to me was the fact that the lake was both a bottomless pit and a perfectly-flat mirror, depending on which way you looked at it. That’s probably why this is my favorite photo of the trip—somehow the camera managed to look at things both ways.

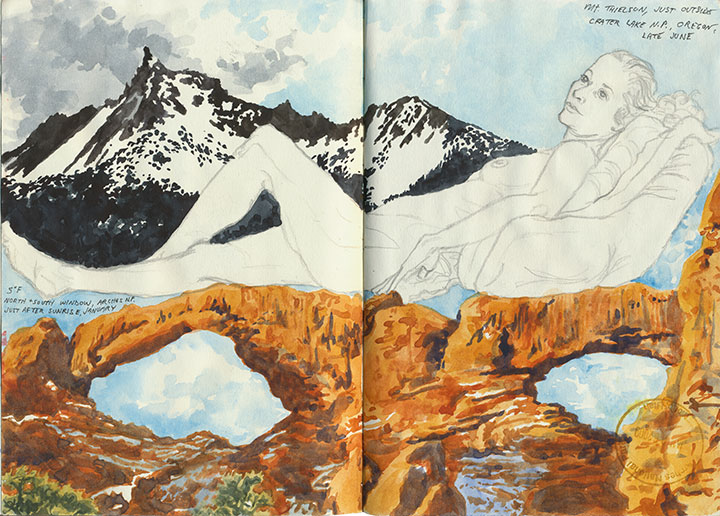

I think I must have been trying for the same kind of perspective with this drawing—and with far less success, I’m afraid. My brain broke when I tried to analyze the thing graphically. Ah, well. (The ground squirrels were fun, though.)

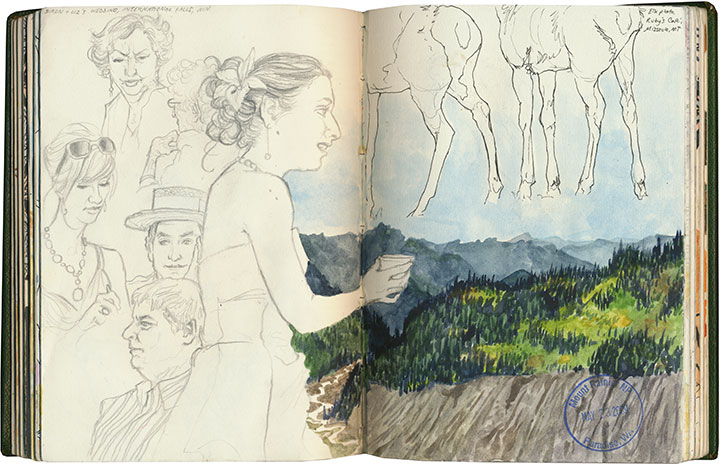

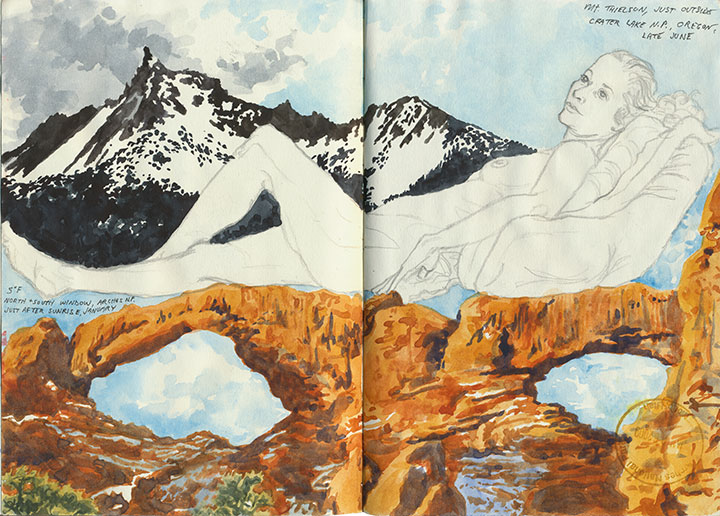

This one worked out a lot better—and it didn’t hurt that the figure and desert drawings were already there to help things along.

Speaking of deserts, we also saw a whole lot of barren landscapes to balance out all this snow and water. For one thing, we drove down and back on the eastern (the arid leeward) side of the Cascades. For another, there are places where all this ancient volcanic destruction still looks like it happened last year. This is the Pumice Desert, on the north side of the National Park.

And this is something else again. Now, I loved everything we’d seen at the Park, but my absolute favorite part of the trip was this place, which made for a side trip on the way home. This is just south of the Newberry Caldera, another collapsed volcano formed in precisely the same way as Crater Lake, but on a much smaller scale. A trail winds up and through the rock-pile hills—a landscape that seems plucked from the surface of the Moon.

If you step closer, however, you’ll see the light glinting off of each rock and pooling in every crevice. In full sunlight the entire hillside sparkles like a gigantic, blinding treasure hoard.

The rocks shine because they’re not rocks—they’re glass. This is obsidian, a natural glass formed when lava cools rapidly without crystallizing. Besides being gorgeous and just about the coolest thing ever, obsidian is extremely useful as a surgical tool. Obsidian scalpels can be sharpened to a near-microscopic edge (because of the not-forming-crystals thing), and the incisions they make produce narrower scars than steel scalpels do. Neat, huh? Anyway, obsidian flows of this size are quite rare, so if you get the chance to walk through one—take it.

I could have stayed all day with the obsidian (which, by the way, is called the Big Obsidian Flow, a name that gives Deep Blue Lake a run for its money), but we were still several hours from home (we figured we’d have to spend the first hour stepping carefully around all the ground squirrels that had appeared at our feet), and we still had one more stop to make:

Lava Butte, from which it was possible to see pretty much every darn volcano in Oregon, and even Mt. Adams in Washington. I won’t bore you with the 200 other photos I shot from up there, but let’s just say I was in suitable awe.

Oh, and for the record? All of these volcanoes are still active. How freaky is that? Or maybe it isn’t, and I just have volcanoes on the brain, but I think it’s freaky.

I lost count of all the volcanoes we spied, but the rest of the numbers were easy to tally:

Five glorious days.

Five breathtaking sunsets.

Five thousand smiles.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)