Blog

September 8th, 2009

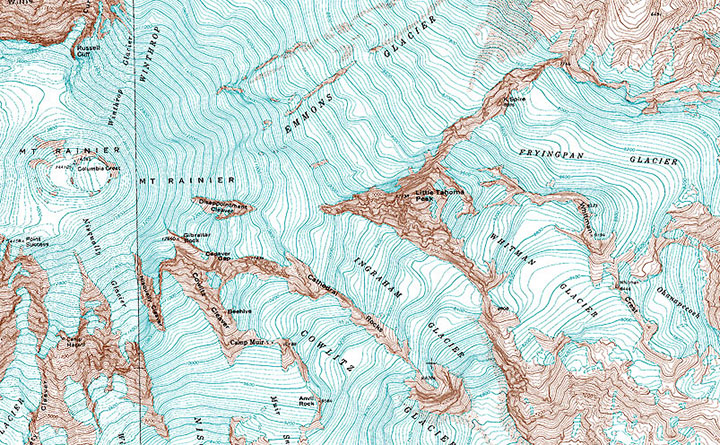

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m currently in the process of researching Mt. Rainier for my next artist book. This involves drawing and photographing the Mountain over and over (and over and over) again, in as many different conditions and from as many different vantage points as possible. I’ll get into the whys and hows some other time, but for now, suffice to say this is a huge challenge. Not only do we have incredibly unpredictable weather here, but Rainier also tends to play by his own rules, appearing and disappearing regardless of any logical connection to the forecast (which, somewhat ironically, is the entire point of my book…).

I’ve done my best to even the odds by doing the bulk of my research during the summer and early fall—traditionally the dry season here. This summer, however, has proven to be about as nontraditional as possible, and has thrown a whole lot of monkey wrenches into the works. For weeks I had planned a long trip to various points east, where the landscape is drastically different than here in the west. But here’s the rub: not only did I require a flawlessly sunny day to view the Mountain from so far away, but the best time to view Rainier from the east is in the morning—I’d have to leave too early to see that day’s weather report. So I waited, and stalked the National Weather Service, and packed and unpacked my gear. During our ridiculous heatwave we had day after day of beautiful sun, but hot weather makes the atmosphere so hazy that even from here, just forty miles away, Rainier was just a faint silhouette. And then it was one excuse after another; either I had an appointment or deadline I couldn’t change, or it was raining, or it was hot and hazy east of the Cascades, or there was a forest fire blocking my path (no joke!). Over a month went by like this, and I could feel my window of opportunity shrinking—many of the roads included in my plans are closed from October through June.

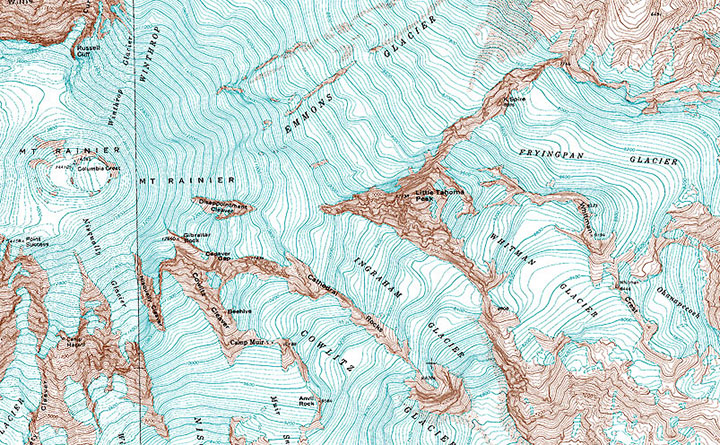

And then, a couple of weeks ago now, it seemed I’d finally get my chance. Every weather report promised dry, cool, sunny weather, for one lovely day, before the gloom closed in again. I packed my drawing paraphernalia, both cold and hot weather gear, a picnic lunch, a pile of atlases and topographic maps (you didn’t think I’d be using GPS, did you? When a letterpress printer marries a geologist, topo maps become a permanent fixture of both studio and science lab!), my camera, and plenty of music in the car, set the alarm for 3:15 am, and went to bed early with my fingers crossed.

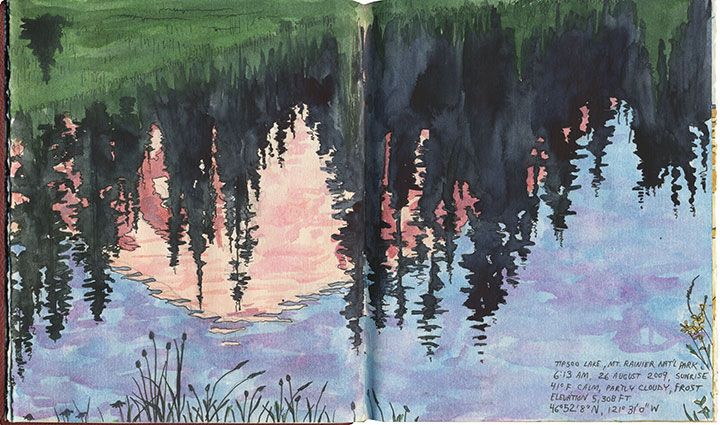

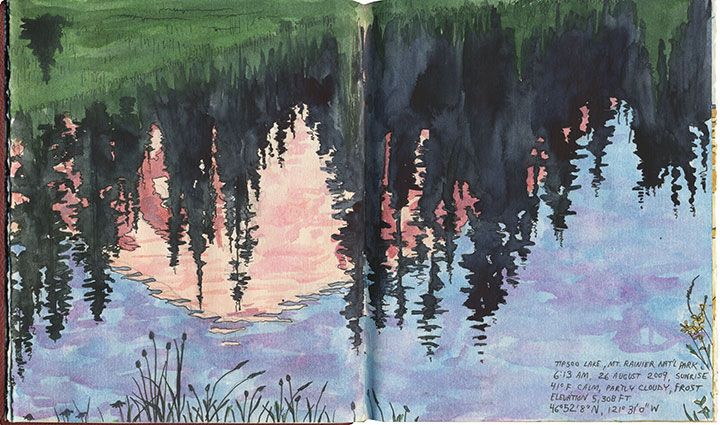

By 3:30 I was ready to go. I poked my head outdoors, saw stars overhead, and decided to make a break for it. Two hours later I arrived at my first stop: Tipsoo Lake, just off the road in an alpine meadow. To my immense surprise I wasn’t alone, even at that absurd pre-dawn, Wednesday hour, with the entire meadow blanketed with frost. A pair of photographers arrived just minutes after me and set up tripods nearby, and a friendly Slovak couple emerged from their tent to introduce themselves while we waited for the sun to rise. The biting cold made me question the sanity of this trip, but when the light finally spilled over the ridge to dye the Mountain pink, all my doubts disappeared.

I stayed just long enough to block in a composition and shoot a few reference photos before the light changed and I lost the moment (I was on a tight timetable all day, so I finished all of these sketches back in the studio). I checked my watch and hit the road again (and waved to the Slovaks as I passed them again, thirty miles later).

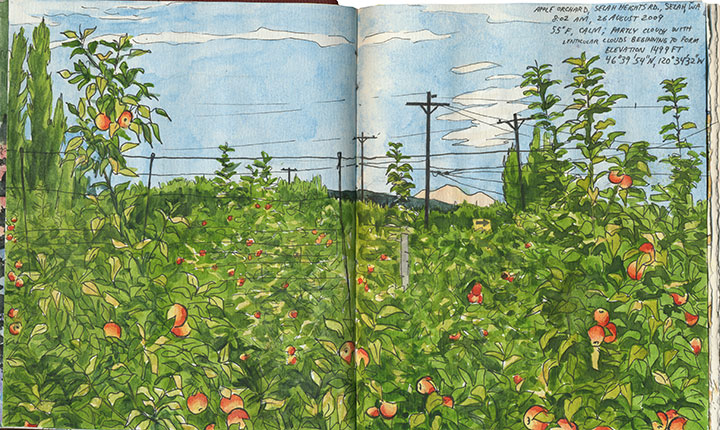

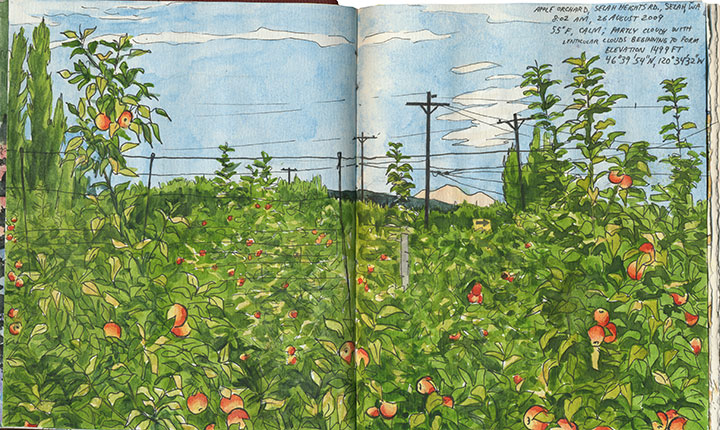

From here onward I had to work entirely on conjecture. Tipsoo Lake is a famous, oft-photographed spot, so I knew what sort of composition I wanted. But I had no photo reference for the rest of my guesses that day, only an idea of what I was looking for and a lot of half-memorized topographic maps. I was hoping to capture a scene of Rainier through the iconic apple orchards of Yakima, but I knew (from all the neck-craning I’ve done on previous drives through the region) that for the most part Rainier isn’t visible from the Yakima Valley, where most of the fruit trees are. According to my maps, though, there were some flat, gridded regions at the top of the bluffs overlooking Yakima—I hoped the grid meant farms, and that the extra 600 feet in elevation would be enough for a glimpse of the Mountain. So I made for Selah Heights Road—a hairline even on my most detailed map.

The road climbed past rows of poplars, trees laden with fruit and sweeping views of the valley; so far, so good.

And then I found it: just the tip of Mt. Rainier visible between the apple trees. I couldn’t believe my luck. And just as I finished roughing out my drawing (I still had a lot of miles to cover before my next destination, so I worked fast and loose), I glanced to my left and discovered another treat:

Mt. Adams, for a little extra credit.

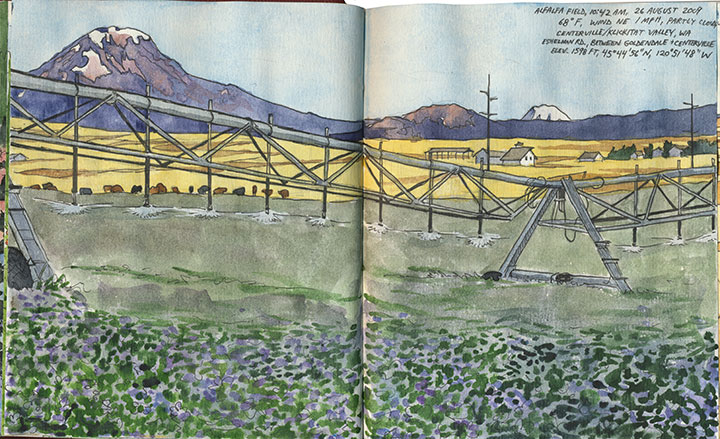

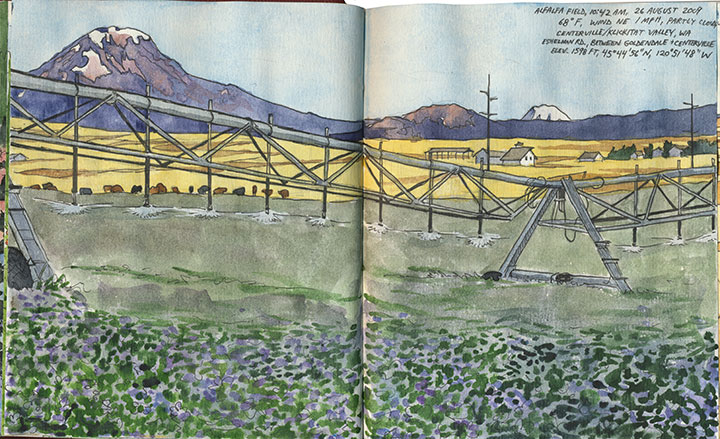

After a quick, desperate and delicious coffee in Yakima, I turned south. My next stop was a place I’d never been: the Centerville Valley, a high-plains agricultural area just beyond Goldendale.

I knew that Adams would be prominently visible from here, but I could only hope that Rainier was as well—it sure would make a pretty picture if it were, I thought.

Nope, still Adams—although from this angle it tends to fool people (and cows).

I looked behind me, and saw that the farmland sloped upward a bit, before giving way to the Columbia Hills. So I headed south along a dirt road for about a half mile, parked, and trudged a few yards into a field of wheat stubble.

Bingo.

The alfalfa blossoms were sheer luck, just like so many other things that day. And that irrigation rig was moving—so I was never more thankful for digital photo technology than that moment (as a die-hard darkroom enthusiast, I never though I’d say that!).

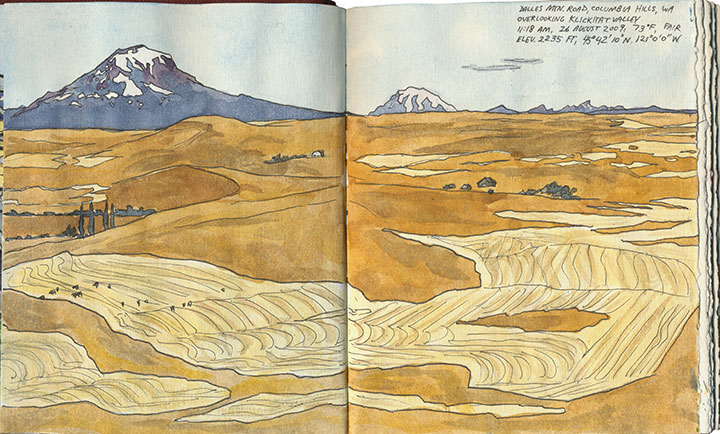

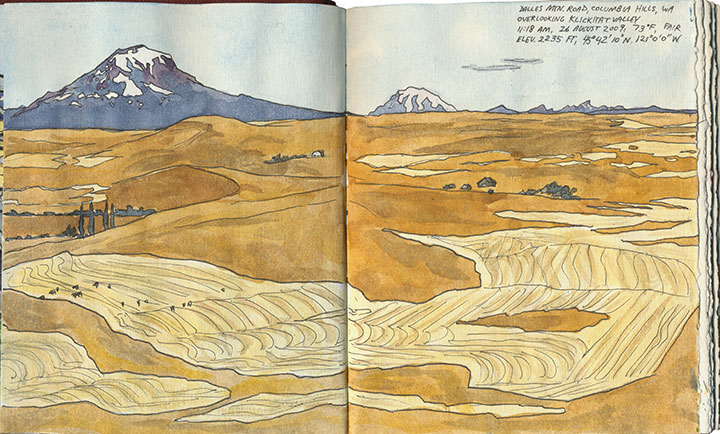

Only one item remained on the itinerary: a narrow, winding goat track called the Dalles Mountain Road.

The spectacular vista of Adams, Rainier and the valley was just the beginning.

The road snakes over the top of the Columbia Hills, providing views of five volcanoes (that’s Hood there)…

pockets of stunning wildflowers…

and plenty of road-side snacks.

On the southern slope of the Hills the landscape turns suddenly rocky,

and the mighty Columbia River bursts into view.

My research had gone off without a hitch, and right on schedule. It was only just noon: mission accomplished. So to celebrate I stopped for lunch at one of the most stunning picnic spots I’ve ever seen.

From that little patch of grass I could have chosen to go home the way I came, or finish the loop and return along the western side of the Cascades—it was almost perfectly equidistant. So as usual I chose the unknown road, and zipped home via the historic Columbia River Highway.

Fifteen hours, 515 miles roundtrip. And perfect conditions every step of the way. I think that after a summer of total frustration (remember the airplane incident?), maybe the universe decided to give me a break.

I’ll be sure to send a thank-you note.

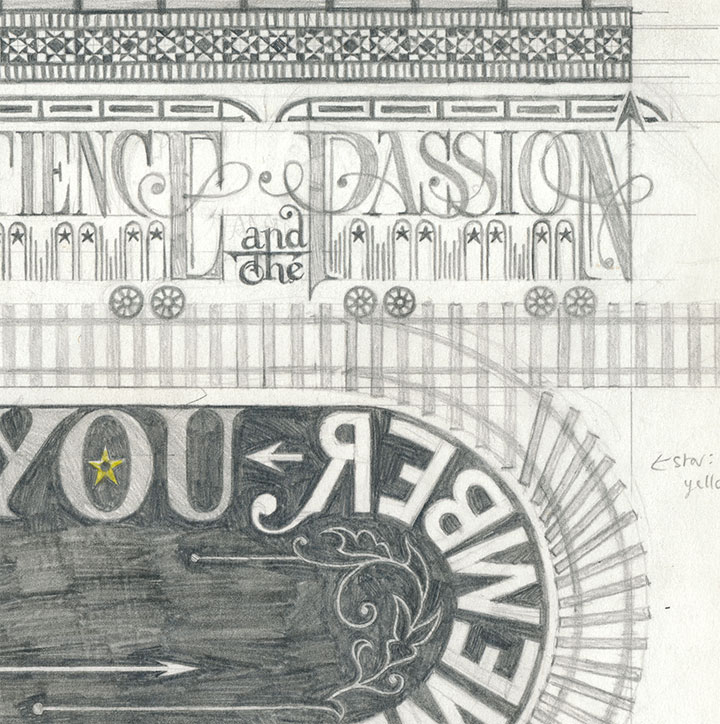

August 12th, 2009

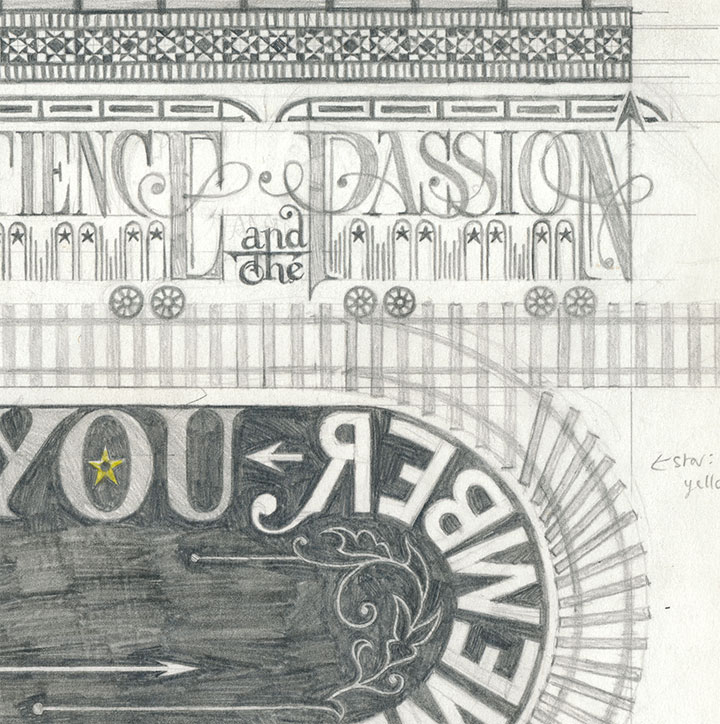

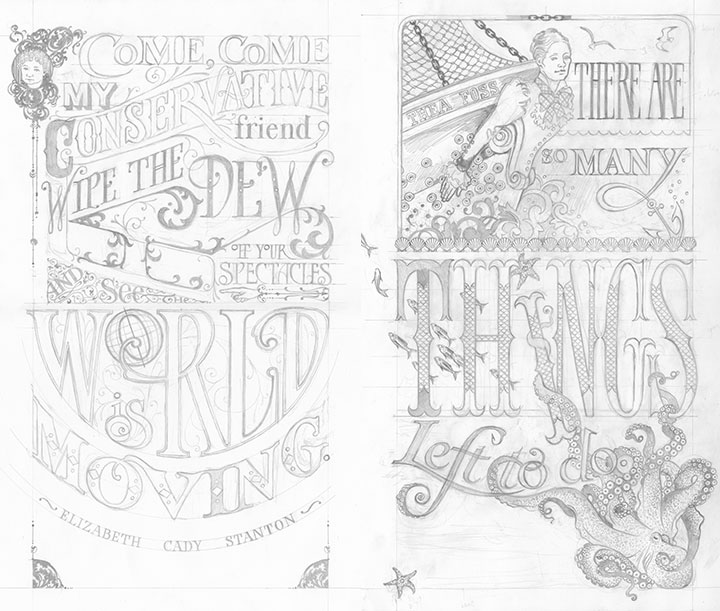

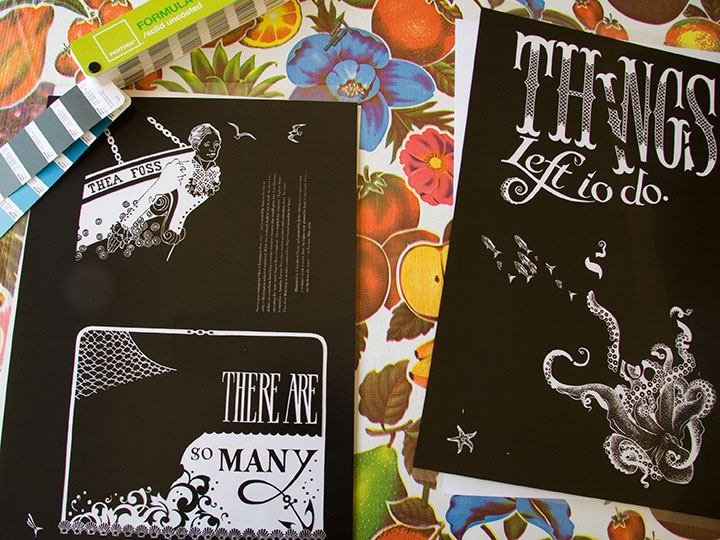

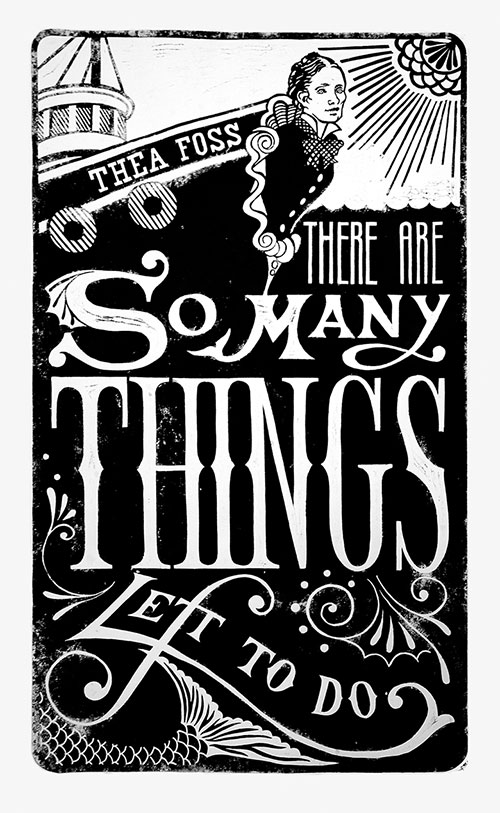

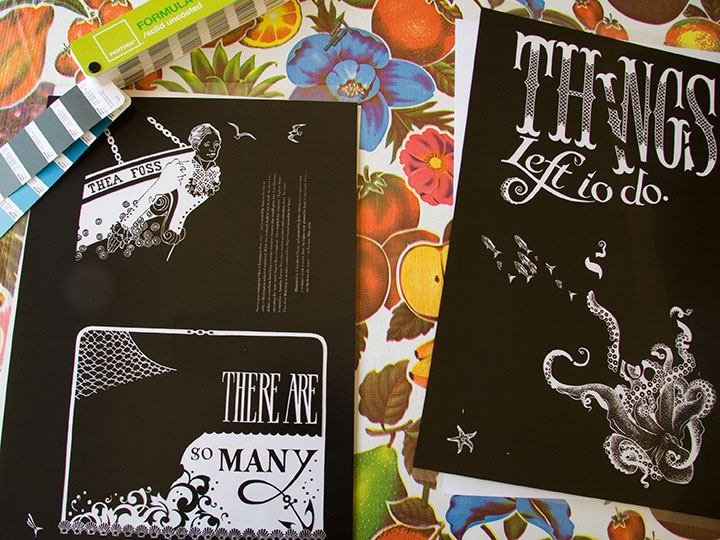

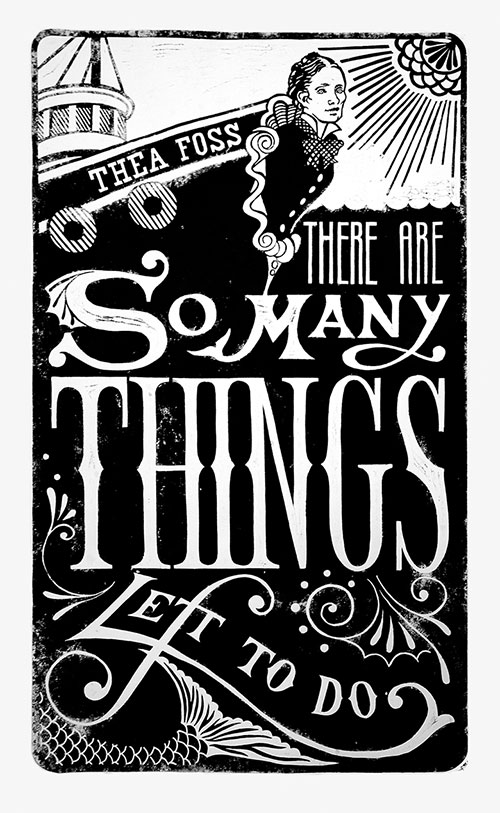

Jessica and I are almost ready to unveil the next Dead Feminist broadside! The ink is drying as I speak, so End of the Line will be available this Friday, August 14. For now, this is just a taste. Brush up on your mirror-reading skills, because this one is going to be a challenge. Stay tuned!

June 30th, 2009

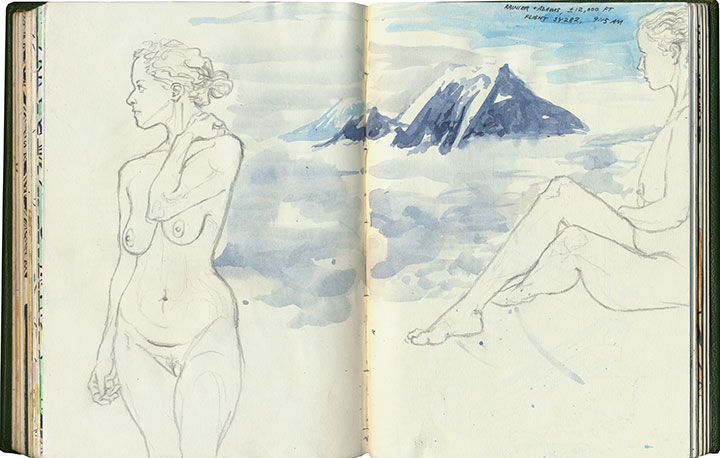

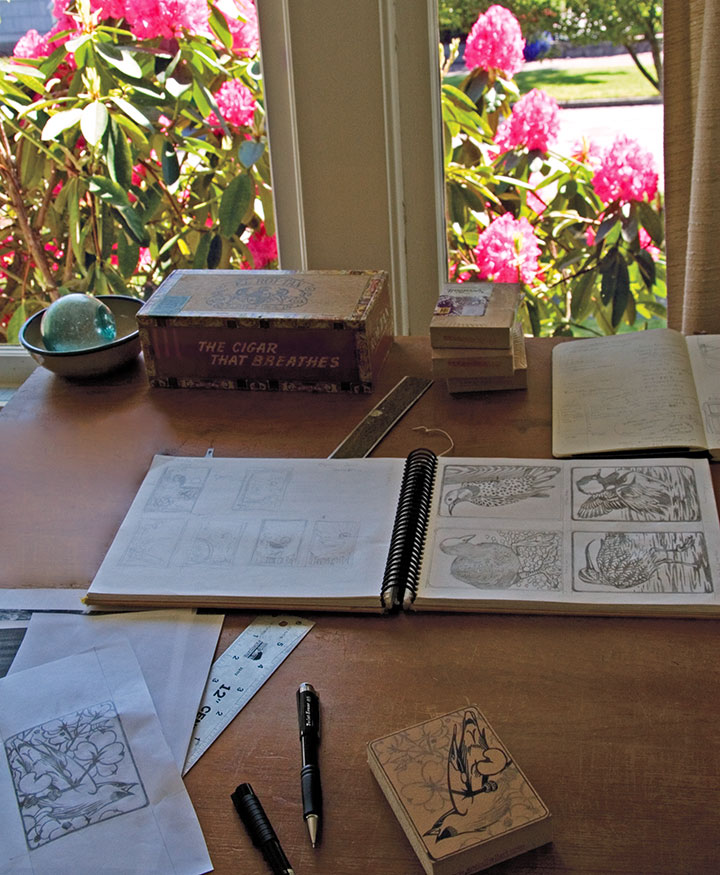

A few months ago I was granted funding by the City of Tacoma Arts Commission to create my next artist book edition. Since this is the first of what will probably be a long string of posts over the next eighteen months, I’ll save the details for later. For now, I’ll just say that the book deals with the changing appearance (and intrinsic nature, since it’s an active volcano) of Mt. Rainier. At the moment I’m knee-deep in research, trying to capture the Mountain in as many different—well, attitudes, as Jane Austen would put it—as possible.

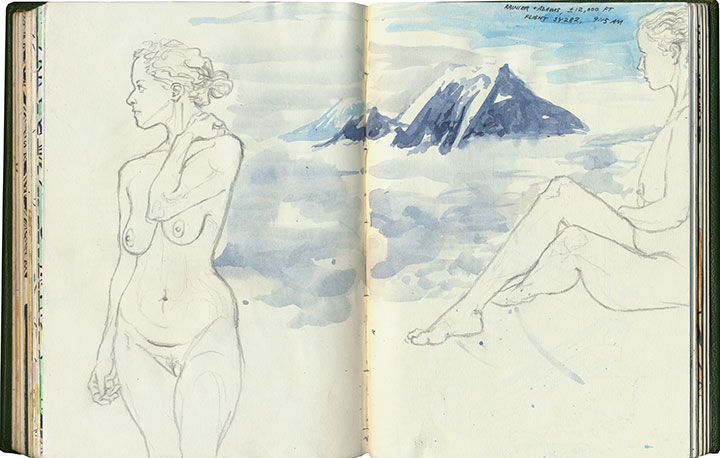

The Tailor and I spent last week visiting old friends and haunts in Minneapolis, and as luck would have it, I had the window seat on the south side of the plane on our flight out. I had my paints, brush, and film canister full of water ready as we taxied, so that when we cleared the cloud ceiling I had a solid two minutes or so for a sketchbook snapshot.

It occurred to me, though, that while a 120-second gesture painting (complete with frantic paint spatter) would be a nice addition to the sketchbook, it wouldn’t provide nearly enough reliable detail to serve as the basis for a future letterpress print. So on the way back, I requested another window seat (I think the fact that I’d sprained my ankle on our last day of the trip, and had to hobble to the counter, might have helped my case a bit) so as to document any Mountain sightings with the camera.

The counter attendant had been kind enough to place me on the correct side of the plane again. And the weather was crystal-clear, affording the passengers with stunning, morning-lit views of Rainier and the entire Cascade volcano chain. The cabin was filled with sounds of hushed awe and clicking shutters. There was only one snag in my research scheme—Row Nine, in which we were seated, seemed to use the term “window seat” loosely.

And the universe kept right on laughing.

June 21st, 2009

There’s some serious gear-shifting going on in the studio these days. Prop Cake and Tugboat Thea are sold out, and the Woolworth Windows murals are white walls again, ready for the next artist to transform the space. I’m preparing to teach a letterpress class at the School of Visual Concepts next month, and I’m working on a new artist book (more on that topic later). I feel like I’m in that tiny, transitional moment between exhale and inhale.

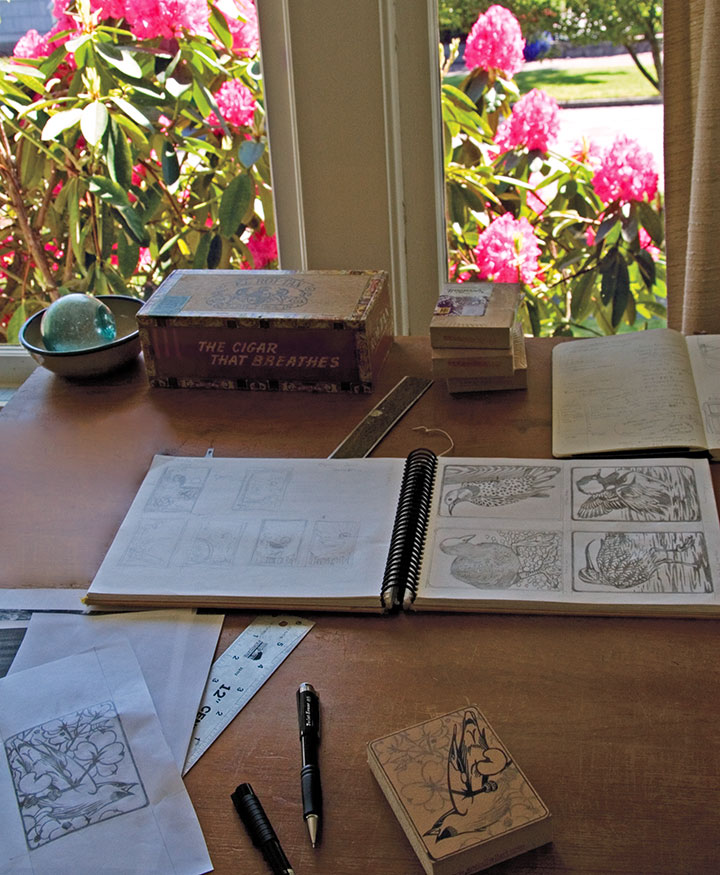

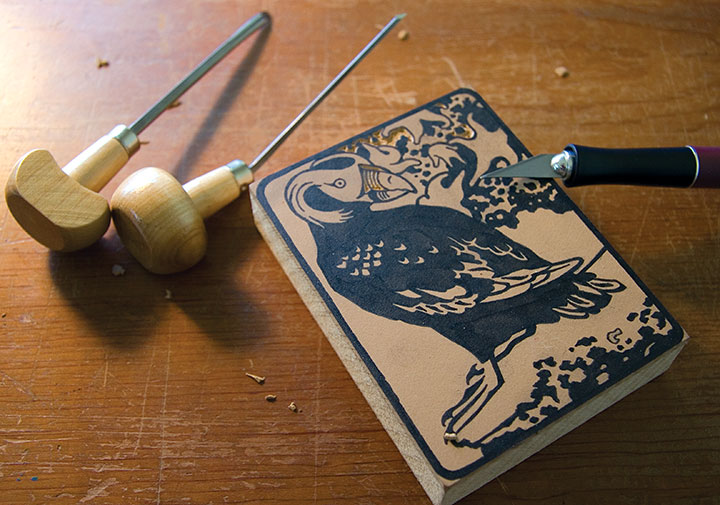

So what better way to use that breath of time than to slow down and do some carving?

In the free moments between my other projects, I’m also working on a new print series that’s got me all a-flutter.

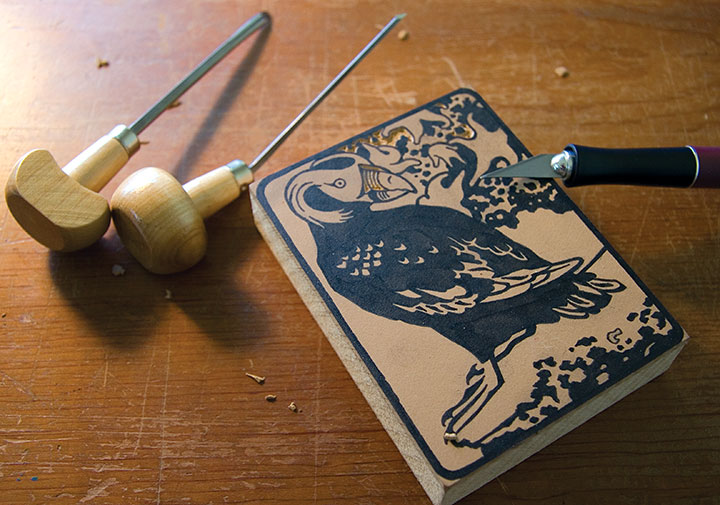

I love getting back to basics, and enjoying the simple mechanics of drawing, carving, and printing images. No fancy photopolymer plates this time—just ink, paper, watercolor, and good old-fashioned linoleum blocks.

What started as an excuse to get my little Kelsey tabletop press in working order—

—has turned into a budding interest in birding. There is a stunning array of avian wildlife in my state, and I’m only creating a tiny illustrated cross-section of what’s out there.

The suite tweet of prints is called Flock, and the first nine are currently on display at the Rosewood Café in Tacoma until July 31.

Here’s a closer look at ’em.

Each print is a hand-colored linocut, printed in an edition of 25. There will be 25 birds in all, and at the end of the series, there will be ten handmade boxed sets—each containing all 25 birds.

I’ll be printing the rest of the birds in the coming months, and the Flock box sets will be finished sometime next year—eight of the ten sets are spoken for already, but if you’re interested, feel free to drop me a line. I’ll just be here in the studio, happily chirping, cawing, quacking, and twittering away.

May 30th, 2009

Oh, I’m probably asking for it with this post title. (To anyone who might have found this post by Googling naughty things, I’m afraid you’re about to be disappointed.)

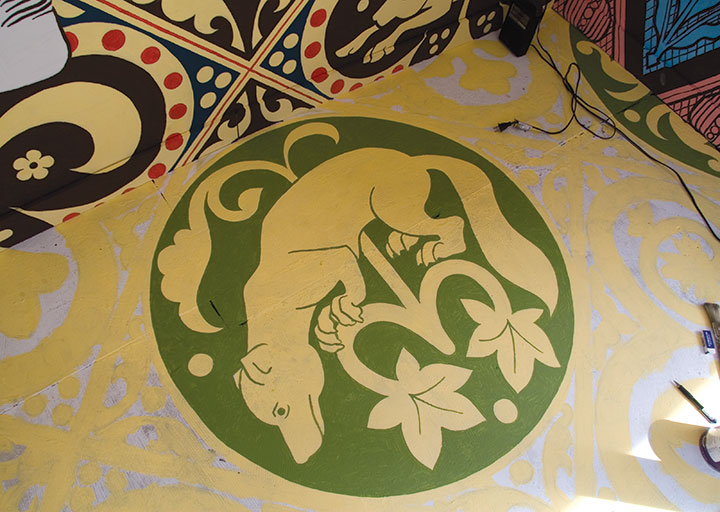

The window displays in the old Woolworth’s store downtown have been converted into a twenty-four-hour gallery, with artist exhibitions and installations rotating quarterly. Shortly after I moved to Tacoma, I found out that they were accepting applications for the 2009 gallery slots. I thought it might be a good opportunity to try out a crazy idea I’d been playing around with, so I decided to give it a go.

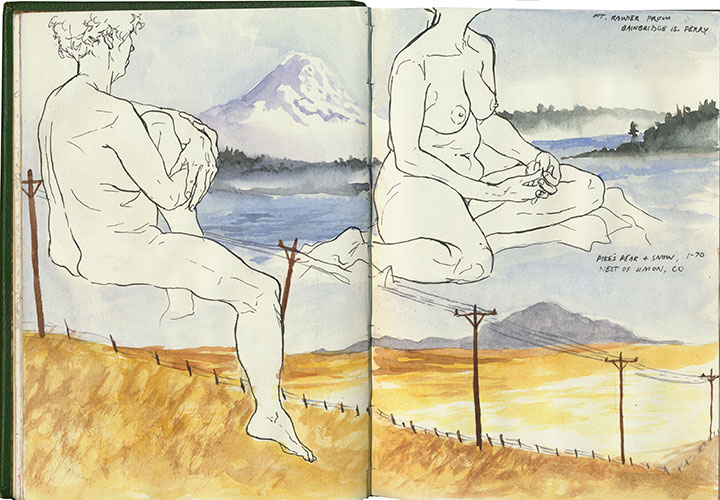

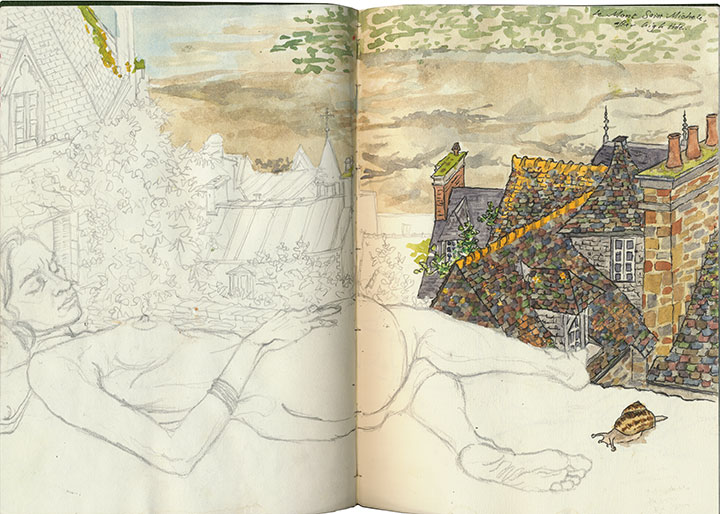

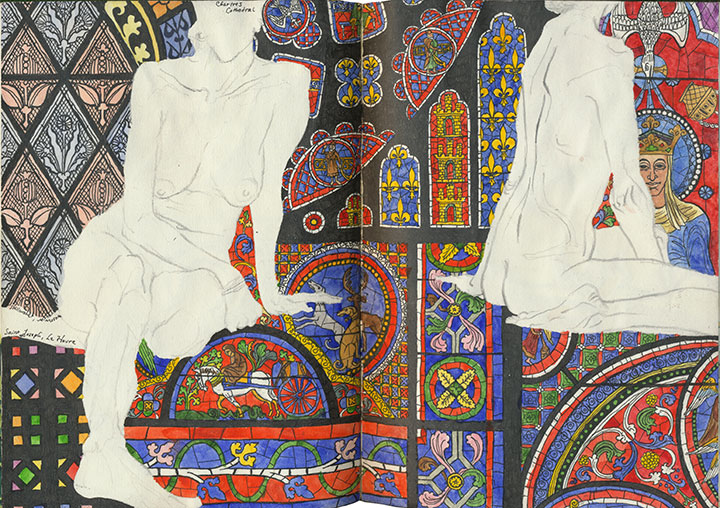

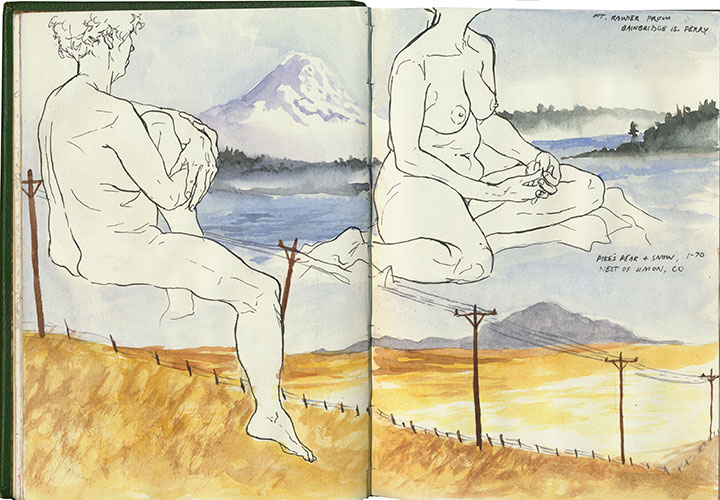

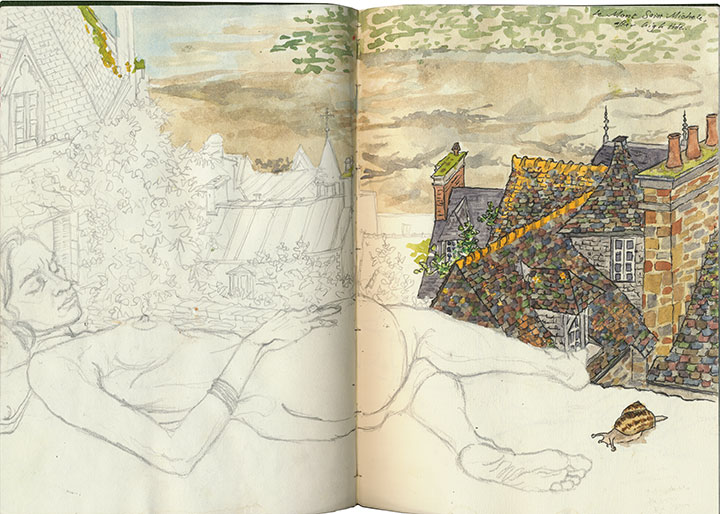

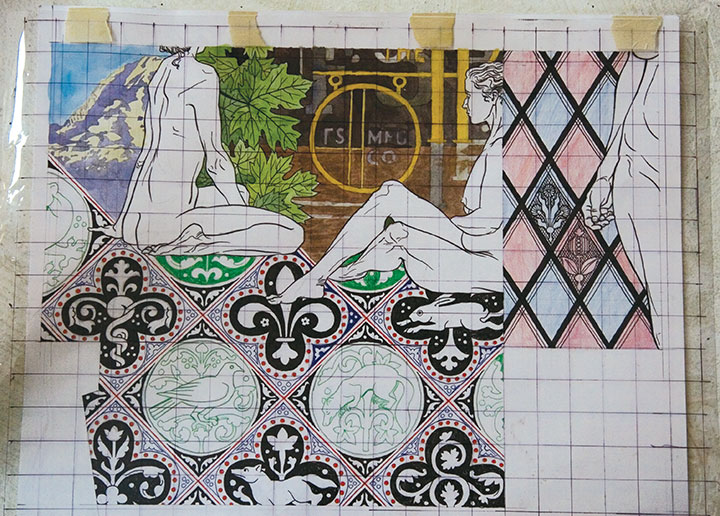

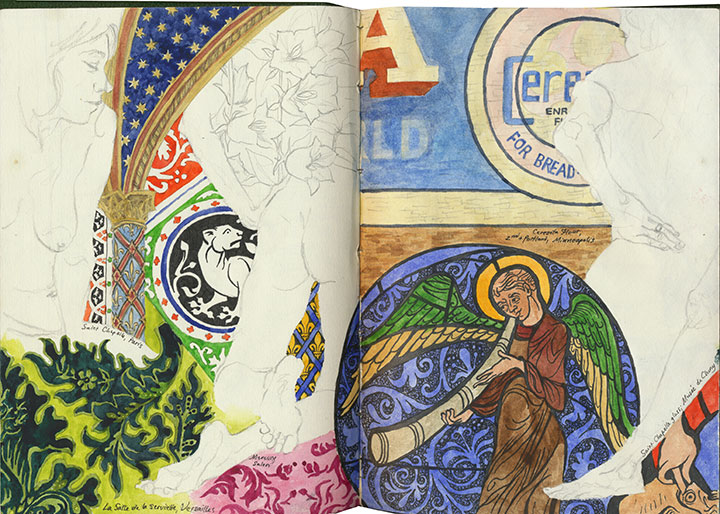

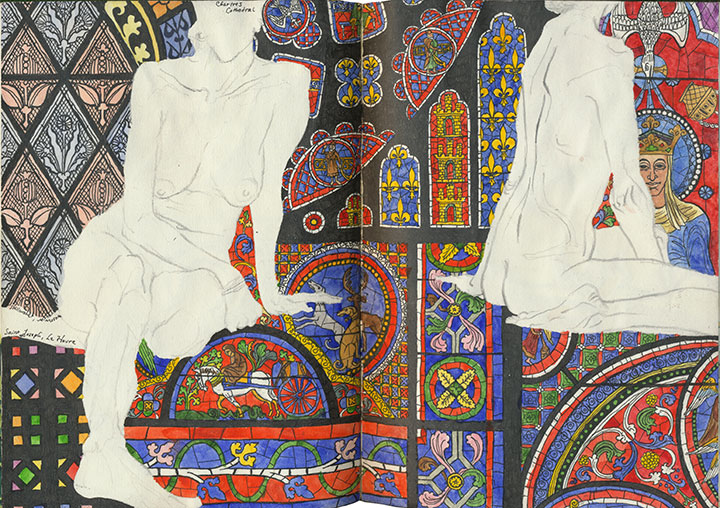

For many years I’ve carried a sketchbook everywhere I go, but for the last couple I’ve been experimenting with something a little different. One day I was in a hurry, and knew I wouldn’t have time to fill an entire spread with the watercolor sketch I wanted to make. So I chose a page that already had some figure drawings on it, and just painted within the negative space around the figures.

And from then on I couldn’t stop. Once the number of watercolor paintings began to catch up with my stock of line drawings, I started attending model sessions again. This time, though, I used the figure drawings to compose the page, with the expectation that eventually I’d go back in with another sketch later.

Several people told me they’d like to see these drawings on canvas or framed on a wall—and more than one suggested a wall mural version. Besides, the conceptual link between nude figure drawings and mannequins in a store windows was too tempting to resist. So I applied for a Woolworth Windows show, but I guess I never expected that my proposal would be accepted. I was talking about gigantic nudes on a busy street, after all. When the notification date came and went without a word, I assumed the project had been rejected and moved on. And then, three months later, I received an email that said, “Congratulations! By the way, your show begins next weekend.”

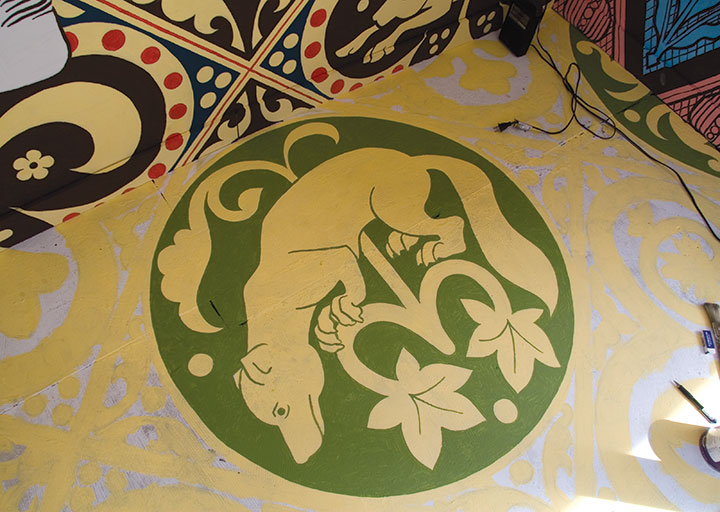

Now, I’m not normally an installation artist, but I do have six years of technical theatre and several large-scale murals under my belt. Still, there was something rather daunting about being thrown in the deep end of a double installation project, which involved attempting to paint proportionally accurate, ten-foot-tall nudes inside a narrow, very public glass box. A very monkey-cage-at-the-zoo glass box. To be fair, every mural I’ve ever painted has begun with a ripple of fear, and thoughts ranging from “Oh, right, I forgot how big walls are,” to “For the love of Pete, how did I ever convince these people that I was capable of painting something that actual humans would be able to see?” Depending on the scale of the project, of course—hey, if blank pages can be intimidating, blank walls (and tall ladders) are pretty terrifying. So this time, what with the many passers-by glancing in at me, I needed a few extra deep breaths. It’s funny that I still get that little moment of panic—because once I finally start in with either pencil or brush, I feel right at home, and even the ladder becomes an old friend. There’s just something so satisfying about slathering paint on a wall.

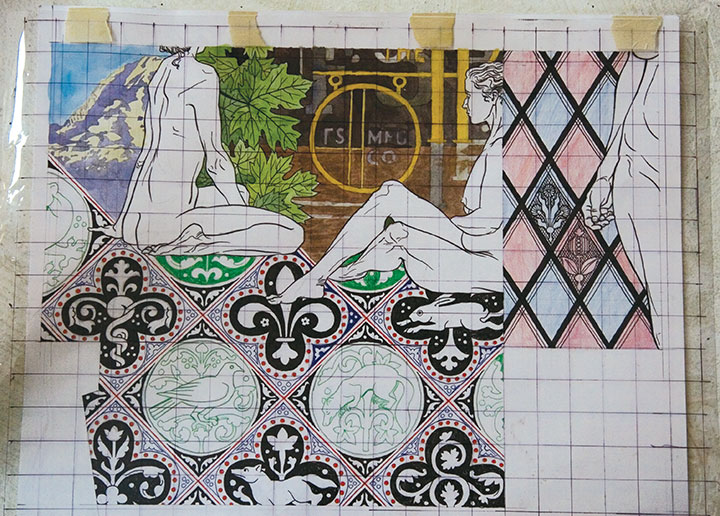

One of the challenges of the Woolworth Windows was getting my design up on the wall, at the correct size, without distorting anything. If I were painting a scenic flat for the theatre, I’d just photocopy my design onto a transparency, hook up a projector, and blow up the drawing to whatever size I needed. In a window display, however, there simply isn’t room to put a projecter far enough away from the wall. So I did it the old fashioned way: made my rendering to scale, laid a grid over it, and drew the same grid at the larger size on the wall.

You can see a little of the pencil grid in the top photo; in the left-hand window the pattern repeats did most of the work for me.

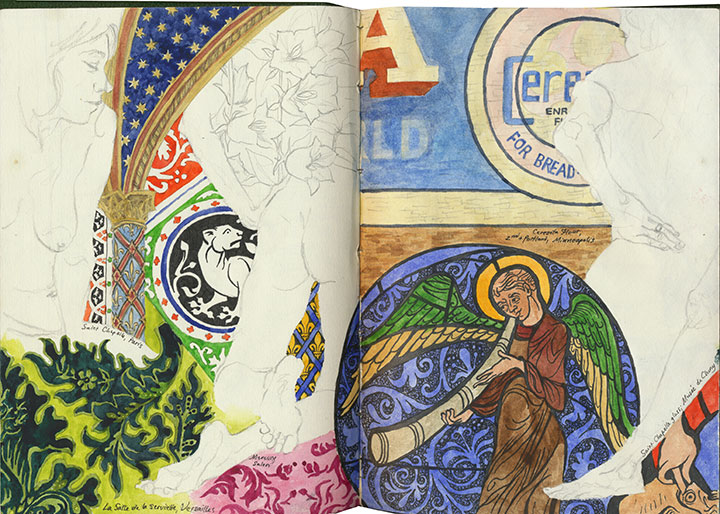

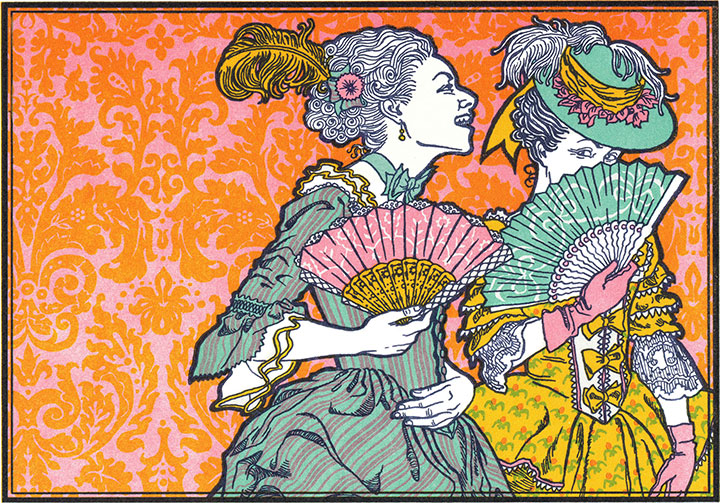

Like the drawings in my sketchbook, the inspiration came from a variety of sources. This pattern was an original design, but I was heavily influenced by the patterned brocades I saw at Versailles (see below).

Another element from this sketchbook page found their way into the design—my drawings of the inlaid floor of Saint Chapelle in Paris became the basis for the floor of the right-hand window.

The windows also contain elements found closer to home: bits of historic Tacoma signage,

and a stained-glass window in the home of my friend Christina, who lives in a former church.

Since I had a lot of equipment to stash in such a small space, I had to paint in a piecemeal fashion,

moving my supplies closer to the door as I painted myself into a corner.

Despite the challenges of the installation, this has been one of the most interesting and fun mural projects I’ve ever done. For one thing, I fulfilled a secret childhood wish to be “one of those people” who designed and created window displays (I was a big fan of Mannequin). For another, the best part about painting in public is that you get to meet all kinds of wonderful people. Everyone I’ve seen has been incredibly supportive, curious, and thoughtful. Mothers wheeled their strollers right up to the window so their toddlers could press up against the glass and watch. School kids on a field trip gathered around my rendering and recognized the Harmon sign immediately. Street-smart teenagers stopped to ask insightful and challenging questions about gender roles in art. Friends brought me coffee on a chilly day, or kept me company when I started to get tired. Business people flashed me a thumbs-up on their way to work, and neighborhood regulars shouted their encouragement through the glass. I guess I didn’t have to worry about the public reaction to a bunch of naked ladies after all.

There’s a catch to all of this, however: the installation is temporary. The last day of my show is June 13, and then I have to paint everything white once more. So stop by while you can—you’ll find these ladies on Broadway, close to the corner of South Eleventh Street (on the same block as the Thursday farmer’s market).

I guess that’s another thing all those years of theatre taught me: how to practice a little detachment when you have to dismantle what you built.

Even if it were only up for a day, though, it would have been worth it.

May 16th, 2009

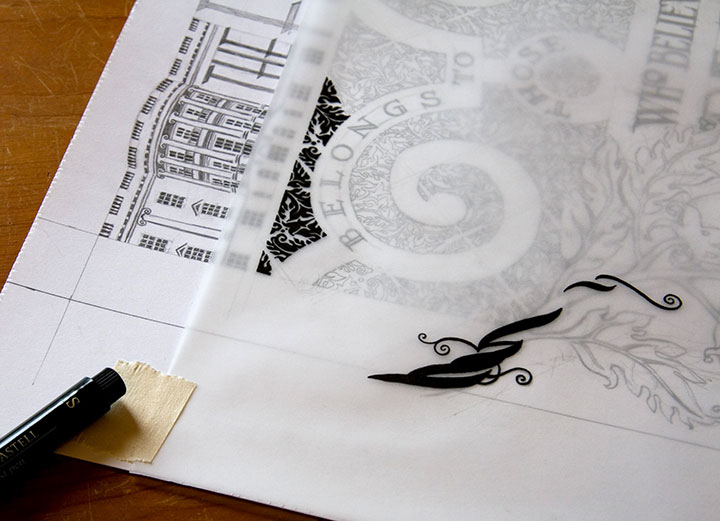

When it comes to letterpress printing, process is everything. And since that process is not always evident in the final product, I thought I’d share the technical aspects of the Dead Feminists series. Now, as I said in the last post, letterpress printing is traditionally done using metal or wooden type—or in the case of the photo above, relief images cut into type-high (.918 inches in the US and UK, in case you wondered) blocks. What Jessica and I have been doing, however, ain’t your grandpa’s letterpress. Thanks to a fairly new technology called photopolymer, we’re able to create our own relief plates right in the studio, without having to carve a block by hand or etch a plate with nasty chemicals. Photopolymer has also created a bridge between the traditional print shop and the modern digital world—as you’ll see in a moment. As far as the Dead Feminists go, Jessica and I still have both feet firmly planted in the traditional world—we just dip a toe into the digital realm now and again. Here, let me explain.

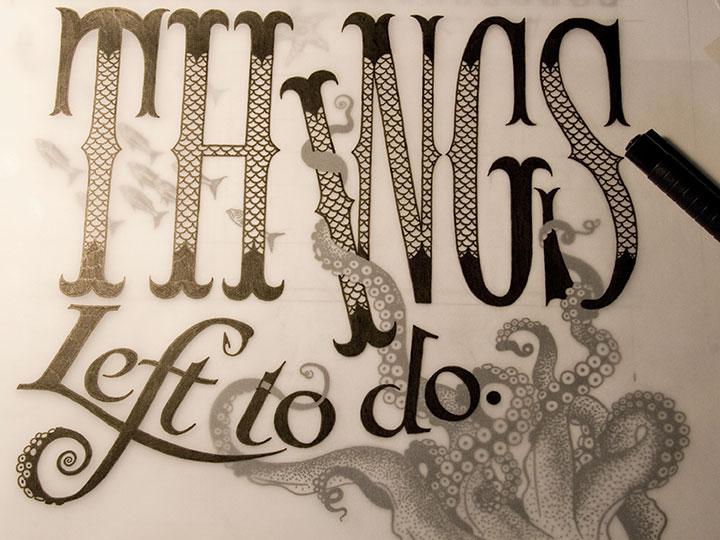

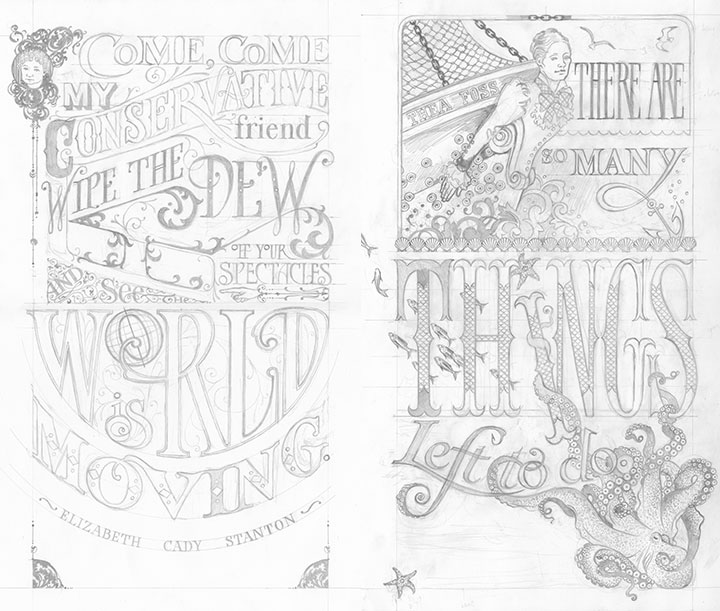

This is how it begins for each print: a pencil drawing, at full size. This is the stage where I not only design and illustrate the piece, but also start thinking about color choices: what the colors will be, what element will be which color, where the colors will overlap, how to make things work logistically. Now, this pencil layout isn’t enough to make a plate; for the photopolymer process to work properly, I have to translate the sketch into a solid black-and-white ink drawing.

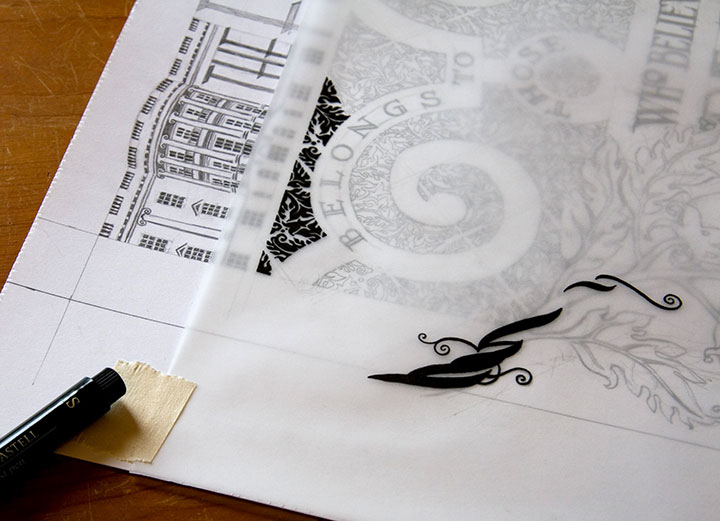

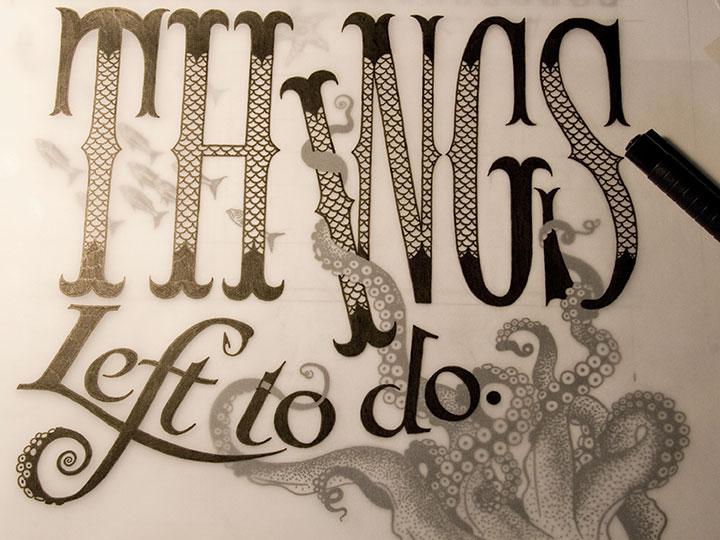

After everything is pencilled in, I lay a sheet of vellum over the drawing and trace everything in ink.

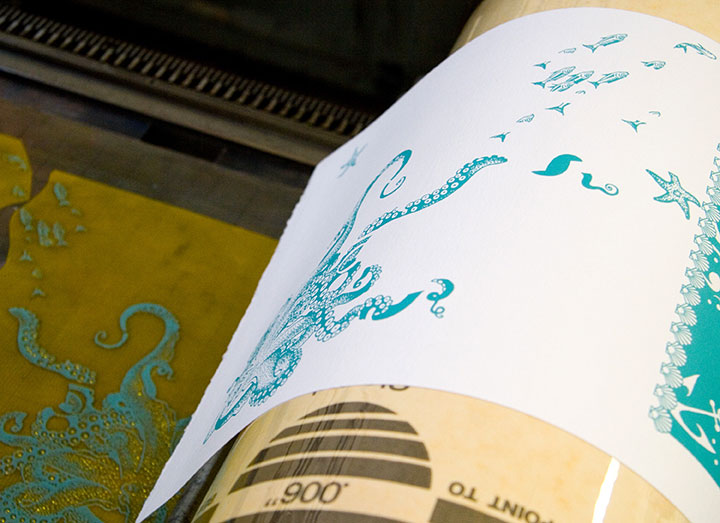

Since each broadside is printed in two colors, each color means a separate run through the press. So as a result, I had to trace each color separately—being careful to stay as true as possible to the original drawing, since the colors had to line up exactly on press. If you were to line these two color separations up, on top of one another, you’d see how the colors will interact in the final piece.

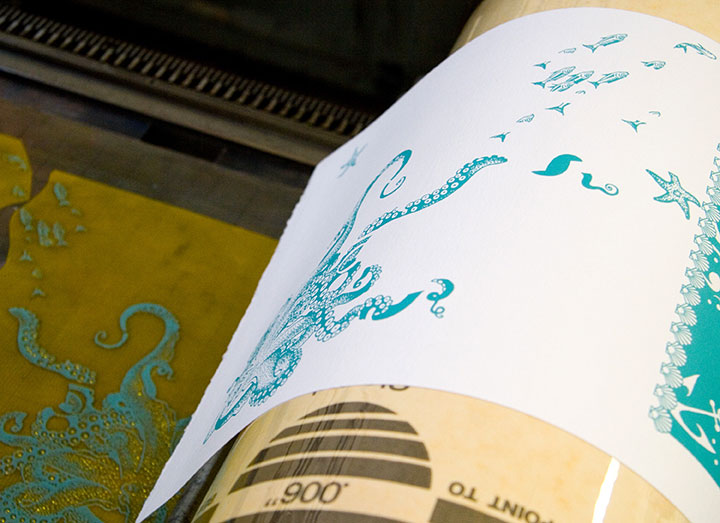

Here’s what I mean. You can see the separation that will become the grey color in Tugboat Thea here, laid directly over the inked octopus below. This is definitely the old-fashioned way of doing things; there are plenty of digital methods of color separation. I guess I just prefer the physical connection between the pen and the hand—even despite the greater risk of screw-ups (as you can see if you look closely at the word “to” above).

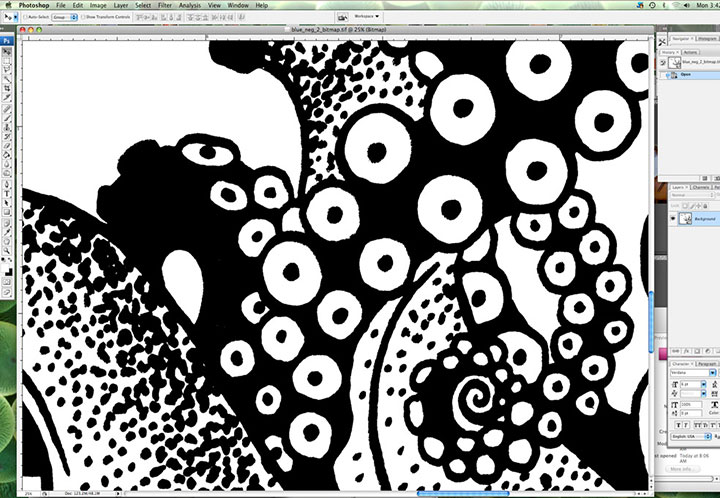

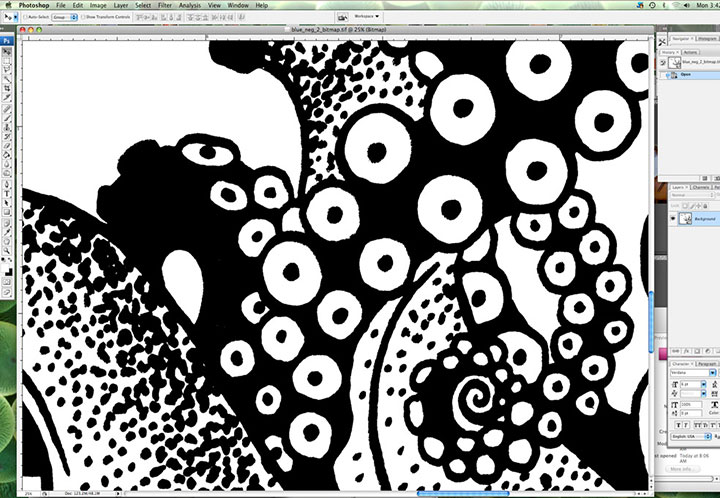

Here’s where I dip that toe into digital waters. Once I’m finished inking, I scan the finished line drawings at a super-high resolution and load them into Photoshop. This is where I clean up any mistakes (ahem) and convert the drawings into bitmap (pure black and white, with no grey) files. Jessica sends me her written colophon, and I set the text digitally. Then I export everything to the proper file type, and send the files to a local service bureau to have film negatives made. So now we’ve gone from analog to digital and back again.

Here are the negatives for Tugboat Thea; grey separation on the top half of each one, teal on the bottom. As you can see, there aren’t any right angles in the bottom half (octopus) of the teal separation, so if you look closely you can see the little tick marks I added (above and to the right of the starfish) to aid with color registration. Those marks line up with a grid etched on the metal base we use to lock up the plates on press; once we had the plates exactly where we wanted them, I simply shaved those little tick marks off with an Xacto knife, so they’d no longer print. Real slick.

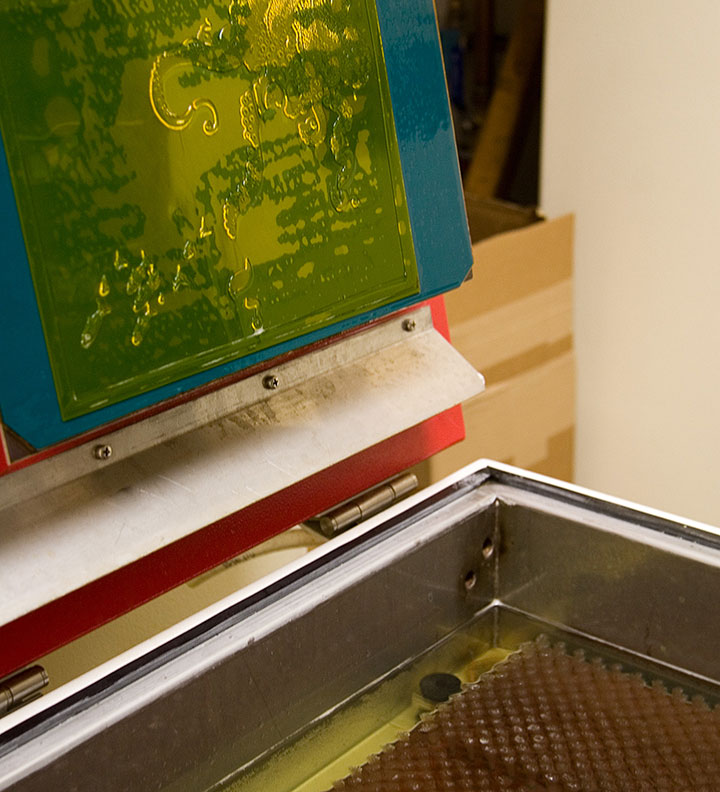

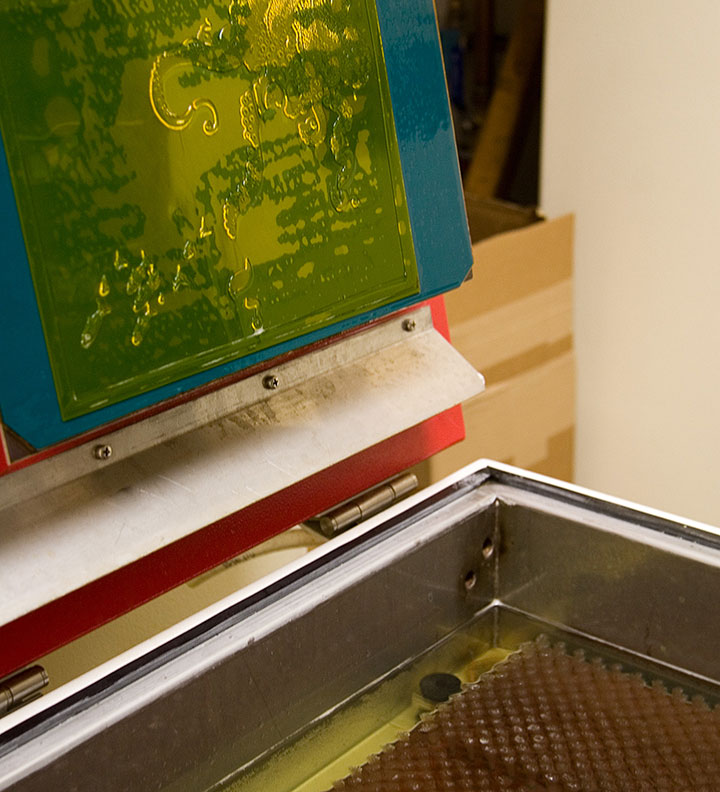

Anyway, photopolymer is a light-sensitive plastic that works just like making a contact exposure in a darkroom does. First I take a negative, place it face-down on an unexposed plate, and load both pieces onto the exposure tray of Jessica’s platemaker (which looks remarkably like an Easy-Bake Oven).

The negative is held flush with the plate by a layer of plastic and a vacuum system; the plate is exposed with UV light (some DIY enthusiasts also accomplish this using glass and a bright, sunny day, but photopolymer is awfully expensive to use in sketchy experiments in the cloudy Northwest).

Next I place the exposed plate in the wash-out unit, where it is scrubbed gently with soft bristle brushes in a tank of cool water. Everything that is exposed is hardened enough to resist scrubbing, while everything else dissolves away. (And turns the water a sickly shade of yellow. Mmmm….plastic byproducts. Still, it’s less toxic than many other printmaking techniques.)

What we’re left with is a raised plate ideal for relief printing. The real benefit of photopolymer is that it can reproduce nearly any image, and can hold an incredible amount of detail. I can transfer my drawings directly to the plate, without adding the laborious step of carving the image into wood or linoleum (backwards!), or etching copper with acid, for example. It’s not exactly an economical option for letterpress printing, but the results can be exquisite, and the possibilities are nearly endless.

Here’s our new octopus plate on press, all inked up and ready to print—it’s stuck to that gridded base with removable adhesive. The thickness of the plate and base together add up to exactly .918 inches. Ah, precision feels good.

And here’s how it looks on paper.

Here you can see the registration between the colors. This is the hard part—I’m sure that despite my best separation efforts and useful tick marks, Jessica is ready to tear her hair out whenever she sees what insane registration issues I’ve thrown at her this time. She’s not a master printer for nothing, though—tiny, 9-point colophon type? No problem! Large, solid color blocks? Bring ’em on! Exacting registration with no margin of error? Sigh. Just get those plates locked up, will you?

Actually printing these broadsides is where all our careful planning and preparation goes right out the window. We can sketch and plot as much as we like, but many of our artistic decisions end up being made on the fly, right on press. Here Jessica is mixing ink for Prop Cake, according to some choices I suggested in our handy-dandy color recipe book.

You can see our original draw-down (color test) in the upper left corner. So far, so good.

The orange turned out exactly as we’d hoped, but when we started printing the pink separation, we hated the result. What looked so good in the draw-down lost all its contrast in the print. It was awful, trust me.

So Jessica changed the color right on press, until we were happy with it.

Here’s the finished product, all lined up in the drying rack.

If lining up the color areas is the hardest part of printing, keeping an eye on the ink consistency was probably the most fiddly. We’re using a very unusual paper for the series—one made from recycled clothing—that is extremely “thirsty.” Not only are there inconsistencies in the paper that can throw off the overall quality of color; but we had to add ink to the press after every fourth or fifth print. As you can see, this is a pretty organic process—lots of variables, small corrections and compromises along the way. (And a whole lot of cursing and starting over.)

All of this is par for the course for a letterpress project—it’s an exacting, sometimes frustrating process, but that’s what I love about it. And the finished product … well, it’s like nothing else. Ah, letterpress, how I love thee.

Now if only it didn’t require several metric tons worth of equipment…

May 14th, 2009

Holy cannoli, everyone! I’ve only just now come up for air—I’ve been buried under invoices, subscription forms, kraft mailers, and email print-outs, and Thea’s face is repeated all around me as reserved copies are spread all over the studio. Since I posted her here on Tuesday night the orders have just poured in, and over three-quarters of the edition is spoken for already. And Prop Cake is disappearing fast, too; we’re down to our last handful. Wow—just…wow. Thank you all so, so much.

Since Thea and her fellow Dead Feminists have left T-Town to be shipped all over the country (and to lovely Canada, France, Switzerland and the UK, too!), I thought it appropriate to share some of the things Jessica and I talked about at TAM the other day with a wider audience. Now, normally my paralyzing fear slight nervousness while speaking to a crowd manifests itself by wiping my memory clean immediately after I give a talk. It’s a very annoying thing, not being able to remember what you just said, but it happens all the time. I guess I’m fortunate that my phobias don’t show up as a quavering voice or profuse sweating (so nobody ever believes me when I say I get stage fright), but selective amnesia isn’t much of a fair trade for fake confidence! But this time, weirdly, it didn’t happen—I remember almost everything, and I think it’s because I wasn’t alone. (Jessica, I reckon that means you’re doomed to be my speaking partner from now on!) So to make sure my memory stays put, I’m setting it down here for the record. (By the way, since there’s rather a lot to say on the subject, I’ve decided to break it into two posts.)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

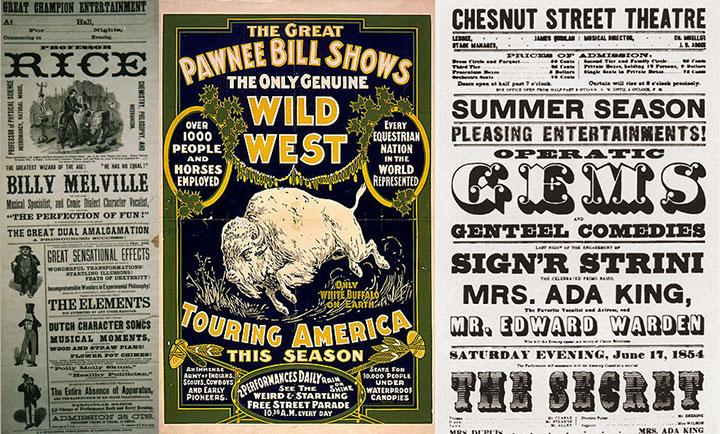

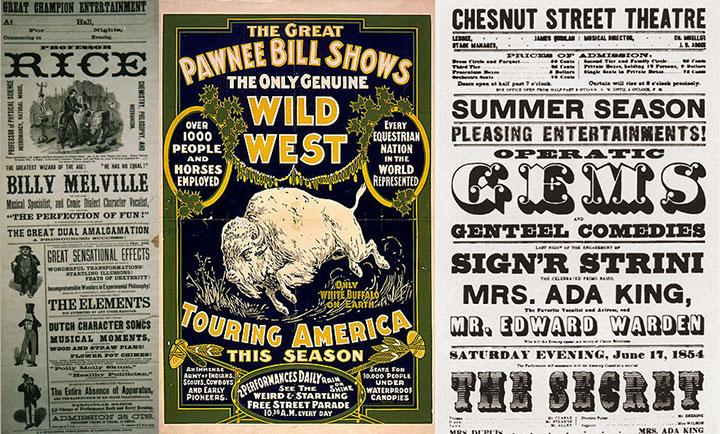

Before I get into the technical details behind our series, I should probably share a little background information on letterpress and the art of the broadside. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the process, letterpress printing refers to a type of relief printing, where pressure is applied to a piece of paper placed over a raised form that is covered with a thin layer of ink. This pressure transfers the inked image onto the paper, and can be repeated to create a batch, or edition, of prints. The form can be a carved block of wood or linoleum; a raised plate made of magnesium, photopolymer (plastic) or other materials; or as the term letterpress implies, movable type made from metal or wood.

The innovation of printing words from individual letter blocks that can be rearranged and reused was actually invented by the ancient Chinese (seriously, what wasn’t originally invented in China? We owe those folks a whole heap), but the process that evolved into modern letterpress was most famously perfected over 500 years ago by Johann Gutenberg, of Gutenberg Bible fame. By the first half of the twentieth century, when more modern commercial printing came along, it was still common for printers to perfect their layouts using movable type and relief-cut images on a proof press (such as Jessica’s Vandercook below). They’d then use the resulting print to make more sophisticated plates for their more efficient and advanced commercial presses.

Jessica printing “Prop Cake” on her Vandercook Universal One press

As commercial printing became more streamlined, the cylinder and platen proof presses (see photo above) fell out of vogue, and eventually were no longer manufactured. Artists quickly saw their potential, however, and have adopted letterpress printing as an art form—using, refurbishing and maintaining this antique equipment to create original works of art.

Hand-in-hand with letterpress printing, the art of the broadside has also survived and evolved into a modern format. The term broadside means any single sheet used to convey information, often of a political kind—the great-grandpappy of the modern poster. While today the words broadside and poster are sometimes used interchangeably, the broadside has remained a favorite of the letterpress community because of its emphasis on typography and content (hey, we need an excuse to use all that gorgeous metal type!).

Jessica and I had this history in mind when we began the Dead Feminists series. As I said before, we never dreamed of starting down the path we’re on now; we just wanted to make a political and artistic contribution to the election. And to pay homage to the history of the broadside and the era in which each of our feminists lived, I designed each piece with historic broadsides and posters in mind. And to keep the series consistent, Jessica and I came up with a few rules of engagement:

1. Each poster has to feature a quote by a feminist. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a woman, but there are already plenty of posters highlighting the words of dudes, so we figured that one was covered already.

2. Said feminist must be deceased. (Hence the name.) You’d be surprised how many challenges that’s created for us.

3. Each quote is tied into a current sociopolitical issue or event. This is usually Jessica’s job, as she’s got a particular knack for finding relevant quotes.

4. The whole piece (except the colophon at the bottom, of course) is hand-drawn.

5. We try to stay away from well-worn tropes like “women can do anything men can do!” in favor of broader topics and concepts.

Who knows how long people will be interested in these things, or how many broadsides there’ll be in the series—all we can say is that we’re grateful for the response people have had, and we’re having way too much fun to quit now. The fun of art-making and the joy of the public response aside, the best part of creating this series has been exploring the lives and work of so many inspirational people. “Feminism” has become somewhat of a dirty word these days—mostly because of misconceptions. To us it’s a positive thing, and creating this series is our way of celebrating those who championed far more than just gender equality. Besides, we’d like to make our own contribution to our social history—and using the “power of the press” in the literal sense is the best way we know how.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Coming in part two: the nitty gritty details behind our process.

April 24th, 2009

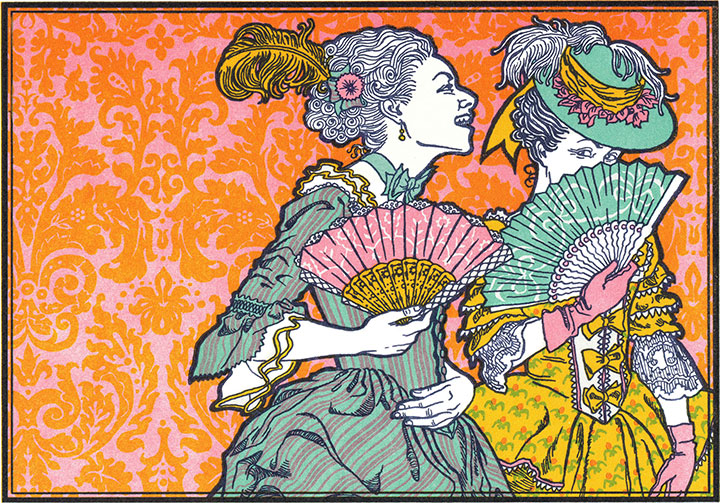

For the past eight months a stack of hand-printed postcards bearing my Versailles gals illustration has lived in the front pocket of my bag—sharing cramped quarters with my sketchbook and watercolors, ready whenever anyone asks for my business card. I’ll admit this sucker was originally designed as a promo postcard, but I kind of like the idea of a gargantuan, six-inch business card—even if you’d need a really big wallet to keep it in.

These days, the question I most often hear is “How can this be letterpress?” I’ve launched into so many long-winded explanations of the convoluted process behind this thing that sometimes I bring visual aids with me to art functions. Yes, I’m a nerd. I carry visual aids around.

Ahem. Anyway, soon I’ll be putting those visual aids to use in the classroom. If you happen to be a fellow Northwesterner, I’ll be teaching a letterpress class in Seattle next month that combines good old-fashioned line drawing with digital typography, and old-school hand printing with snazzy graphic design software.

Johann Gutenberg is probably rolling in his grave right this minute.

Hmm … well, before I get my cosmic comeuppance from the ghosts of my professional ancestors (I also know how to hand-set type, I promise!), here are the details:

Digital Design Meets Letterpress Printing

Six Mondays, May 4 – June 15, 2009, 12 – 5 p.m.

School of Visual Concepts, Seattle, WA

The class is already almost full, so hurry and claim your spot! Let’s give old Herr Gutenberg something to spin about.

April 18th, 2009

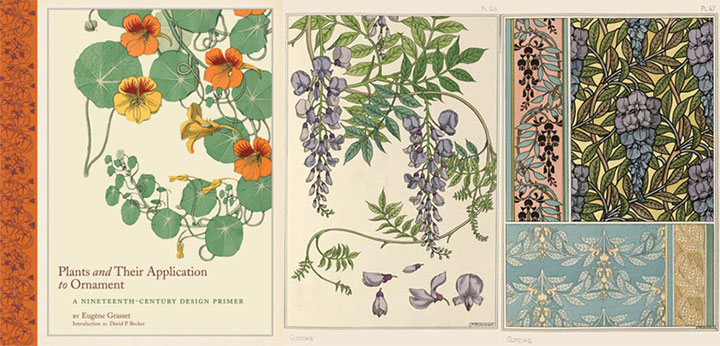

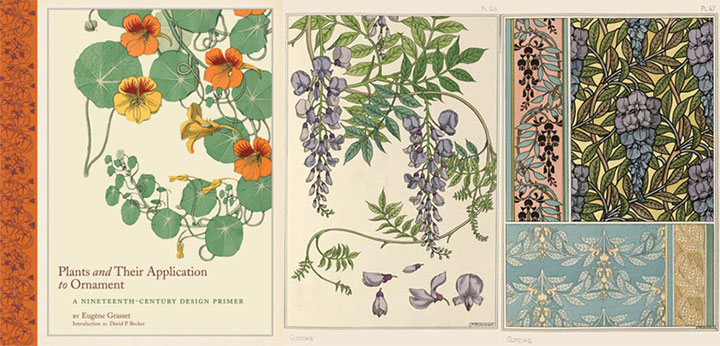

My work tends to deal heavily in flowery typography and ornamental Victorian doodads, so this book has become a constant companion. It’s a reprint of an 1897 design primer, and displays a series of increasingly abstracted renderings of various flora, from realistic illustration to graphic pattern. Most of the patterns in the book aren’t really my cup of tea, but they get the wheels turning and make me think in terms of filtering my sketches and observations into graphic elements. And since I’m in need of some new reference material, both for upcoming letterpress projects and for the new artist book I’m working on (more on that another time), I thought I’d see what spring in the Northwest had to offer. So on Thursday my friend Nicole and I took a little field trip to the Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle and strolled along Azalea Way, cameras in hand.

And boy howdy, those cherry trees weren’t kidding.

Everywhere I turn I hear complaints about how pokey spring has been ’round these parts, but I have to say—if this is late, I can’t even imagine what “early” means. It’s been a long, long time since I’ve lived anywhere that had blossoming trees by early April. We had a late spring in Minneapolis last year, the last spring I lived there—which meant that it was Memorial Day before the blooms had anything to say about it (I know, because I was fretting about the bare trees right up until my wedding that weekend). So I’ll take this Northwestern spring, and be very, very glad.

The sun decided to join us, illuminating every perfect bloom in turn.

A few magnolia varieties were ready for their close-up;

while the saucer magnolias thought they’d sit this one out. But those branches! Each tree looked exactly like a candelabra.

Not to be outdone by the trees, the shrubs and perennials had their say as well.

Even the greenery was super-saturated (no need for Photoshop today!).

I came away with a head full of ideas, and my work cut out for me. Nicole and I weren’t the only artists out that day, either; Azalea Way was just crawling with oil painters, watercolorists and photographers—and other like-minded folk who seemed to have quit their day jobs to do what they love.

The ducks, however, were working overtime that day.

April 7th, 2009

Since my gallery talk on Sunday was limited to a local audience, I thought I’d highlight a few of the pieces in my To the Letter show. (Besides, in a blog post I don’t have to worry about any public-speaking nerves, or hear myself say “Uh” or “um” twenty-nine times a minute.)

The only wall piece in the exhibit is Tugboat Thea, a piece I did with Jessica. The print is an unofficial member of our Dead Feminists series because of its size, and let me tell you, that sucker is huge. (Four feet tall!)

And why is it so enormous? Why, it was printed with a steamroller, of course!

Yes, you read that right. The folks at King’s Books asked us to be a part of their fifth annual Wayzgoose* celebration on the first of March, and steamroller printing was the main event. Thanks to a grant from the Tacoma Arts Commission (seriously, thank you!), each artist or artist-team was given a four-foot slab of linoleum to carve as they saw fit. Jessica and I decided to pay tribute to Tacoma’s own Thea Foss—business pioneer, Waterway namesake, feminist extraordinaire, and inspiration for the Tugboat Annie stories and films.

The trouble was, our Feminist Broadside format relies on a quote by the subject, and we were having an awful time finding anything attributed to Thea herself. Luckily we discovered Finding Thea, the excellent documentary film by Nancy Bourne Haley and Lucy Ostrander—which, by the way, also provided great reference material for sketches.

This should give a rough idea of the scale we were working with. To transfer our image onto the linoleum (backwards, so it’ll print correctly), we photocopied my design drawing at 600% size, placed the copy face-down onto the linoleum, sprinkled it with mineral spirits, and ran a hot iron over the wet paper. The heated solvent transferred the copy toner onto the linoleum exactly the way we wanted it. Then we just had to spend a week carving it!

Here’s the finished block, all inked up and ready to print.

And here’s the print, hot off the press. Nancy, the director of the documentary, even jumped in to help!

Despite weather that absolutely refused to cooperate and ink turned soupy by the rain, the Wayzgoose was a huge success. We had over 500 people in attendance, and every steamroller artist knocked out at least a few prints.

Since the prints are so unwieldy, and since we can only print a handful of them at an event like Wayzgoose, we’ve decided to retool the design of Tugboat Thea. We’ll print a (smaller!) letterpress edition as the next in the Dead Feminists series. Look for it here soon!

I have to say, though, I’m grateful we were able to find a genuine Thea quote—it was either that or this nugget from the old Tugboat Annie stories:

“O.K., ye ol’ gafoozler,” she replied quietly and stood up.

Alright, I admit it: anything using the word “gafoozler” is going to be a major temptation.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

* Wayzgoose (origin obscure): a celebration given by a master printer to his workmen each year to mark the traditional end of summer and usher in the season of working by candlelight. Generally held as an annual celebration of letterpress and the book arts today.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)