Blog

December 25th, 2010

I was afraid I wasn’t going to have any holiday photos to show you—when I was in Portland the other week, my camera took a nosedive after being bumped off my shoulder in a crowded room.

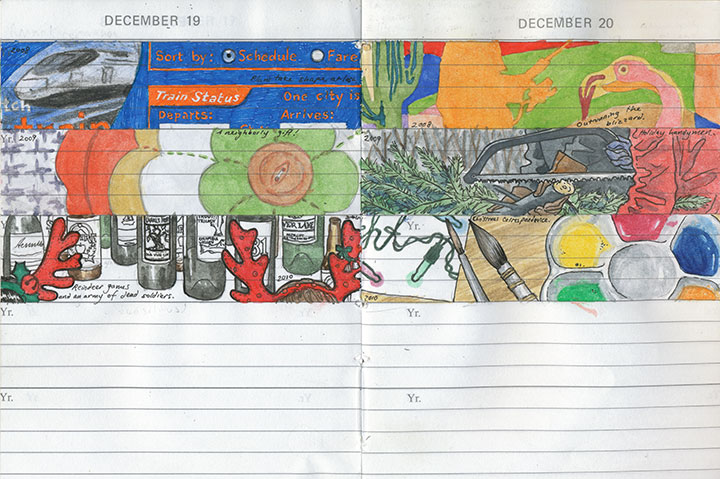

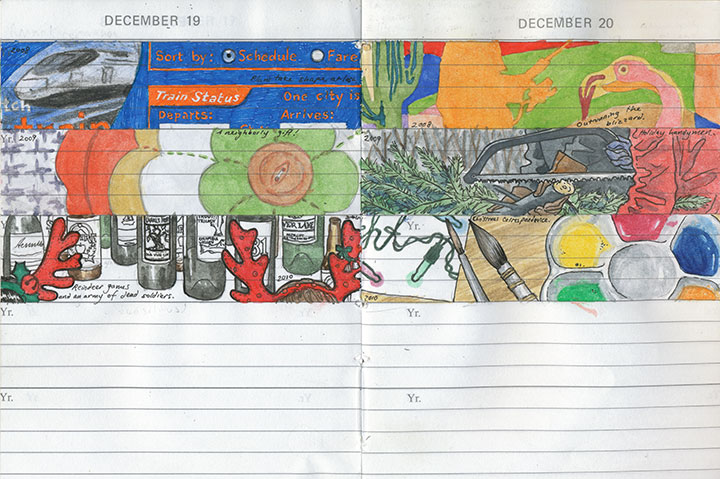

Snippets from my daily journal

So I shipped the lens off to the good folks at Canon for repair, and switched to paper for awhile.

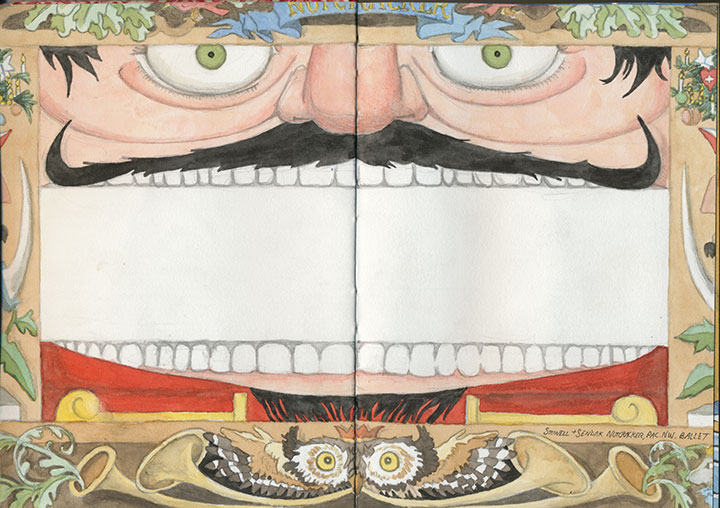

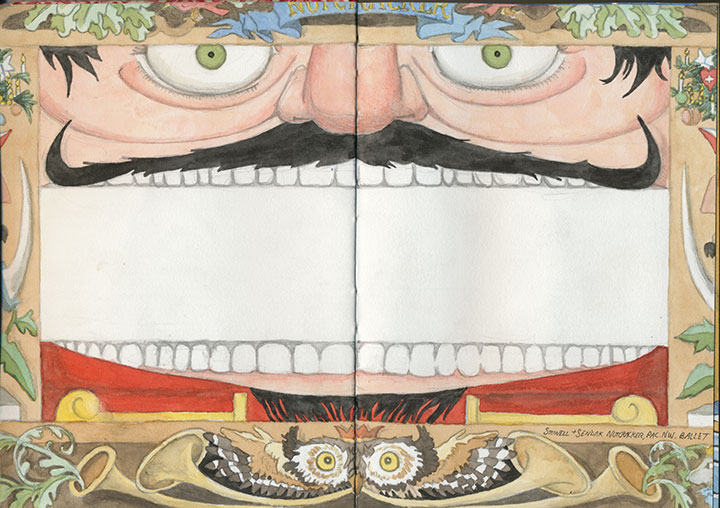

One of Maurice Sendak’s eye-candy stage sets for the Pacific NW Ballet’s Nutcracker

My favorite thing about sketchbooks is that I can take them anywhere—including places where cameras, functioning or not, are strictly verboten.

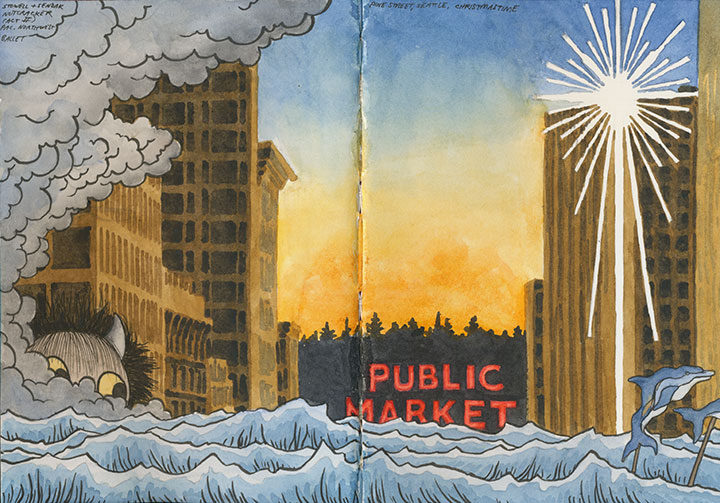

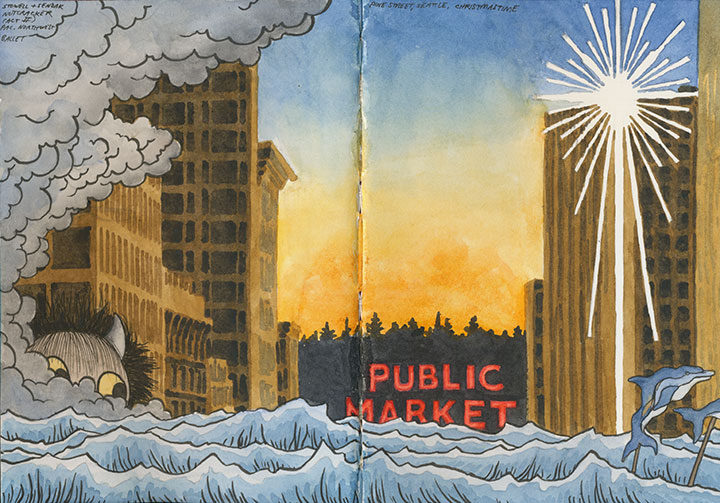

More Nutcracker scenery, plus Christmas on Pine Street in Seattle

The downside, though, is that it takes me a lot longer to draw a picture than to shoot one—so my output is always smaller than I’d like.

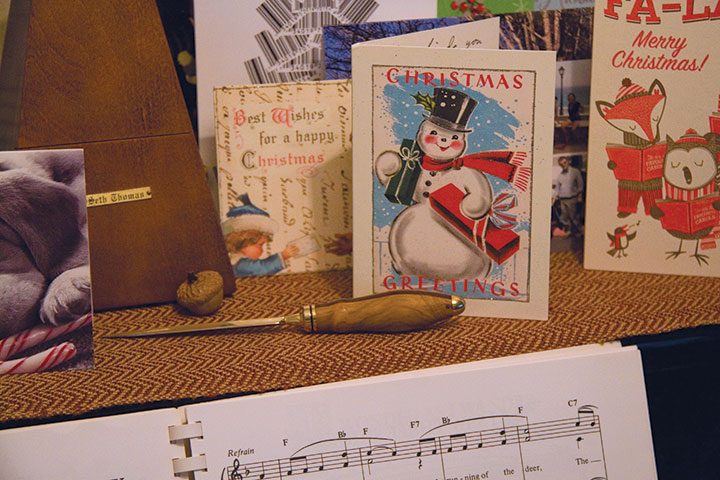

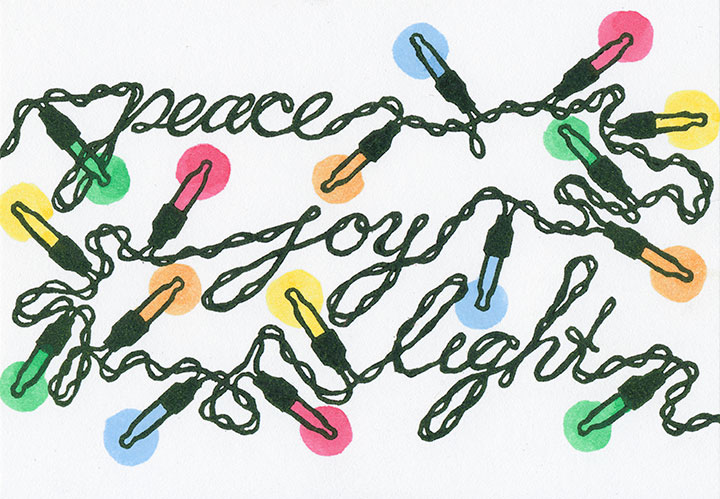

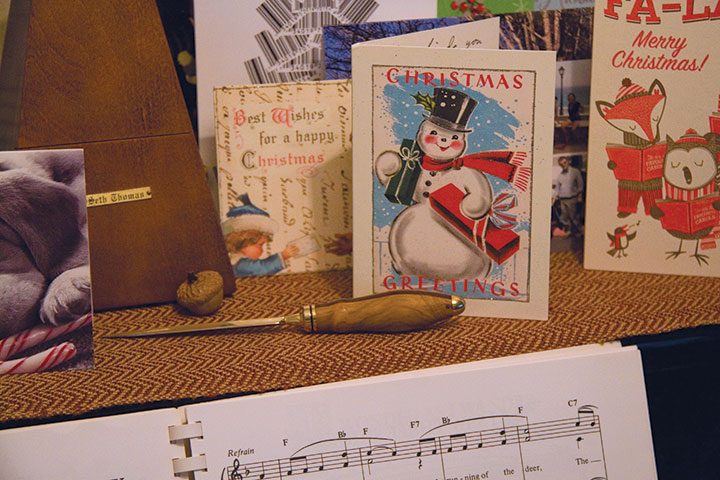

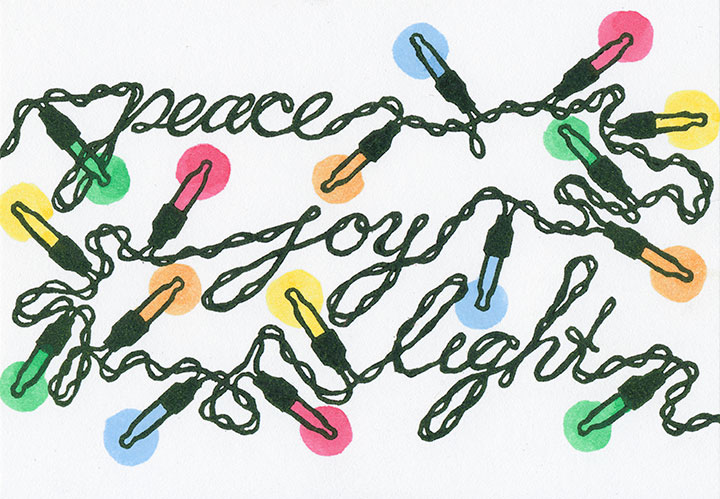

But then the Fedex guy showed up with my lens, good as new and just in time for Christmas.

I managed to refrain from hugging him, and then hopped around the house in manic glee, documenting the holiday the Tailor and I have spent all week creating.

(We finally broke down and bought twinkle lights for the tree; which provided the perfect inspiration for this year’s card!)

Wherever today finds you, have a warm, cozy, abundant, and very merry Christmas.

December 1st, 2010

You know what? It’s pretty dark here in the winter.

No, I mean really dark. Not just a sunrise-at-eight-pitch-black-by-five dark, but a kind of silver pall that sets up a permanent residence, even at midday, and makes you forget about the sun. It’s absolutely beautiful when you’re taking a walk in the fog, or curling up with your trusty Rosie mug and a hank of yarn. Not so great when you really need a lot of natural light, though—like, say, for shooting photographs…

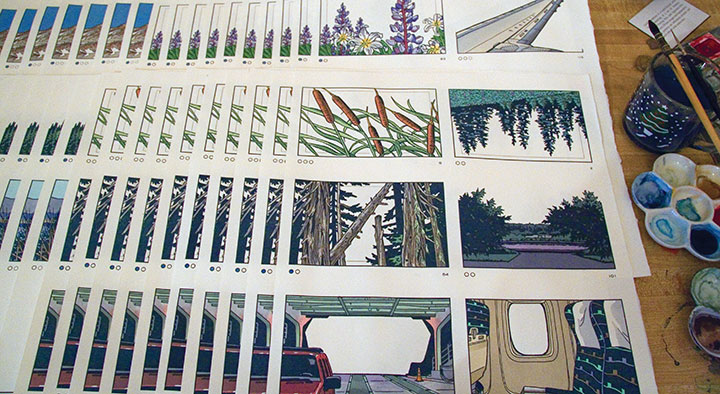

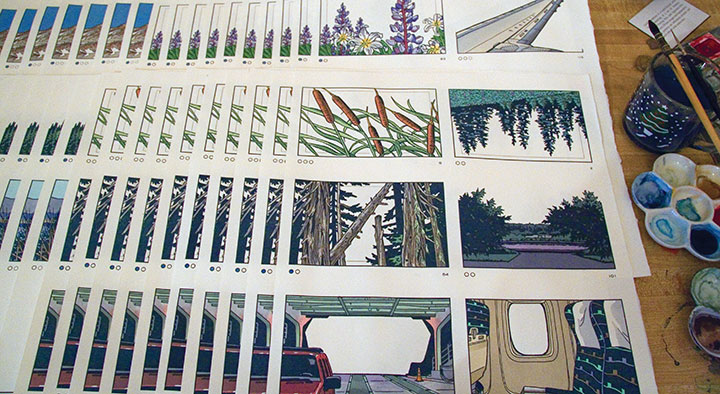

…or mixing paint to fill in a huge stack of glorified coloring book pages.

So between the short daylight hours and a desperate need to reserve a little personal time, work on the book has slowed from a breakneck pace to a stately, clip-clopping trot. I still have so much to show you—so much to explain—but my head needs to catch up with my hands first (or is it the other way around?). I’m going, then, to break it up into a series of posts, and take a little extra time to gather my thoughts before I start. I don’t mean to string you along; because the process required working with a kind of tunnel vision for so long, I’m only just now seeing the “finished” product myself. So thanks for your patience—and for being interested enough to stick with me.

Thank you also for the huge outpouring of support you’ve shown since I posted this thing a couple of weeks ago. The comments, links, blog features, Tweets, emails, and amazing reviews are just overwhelming. I simply can’t find the words, except—thank you.

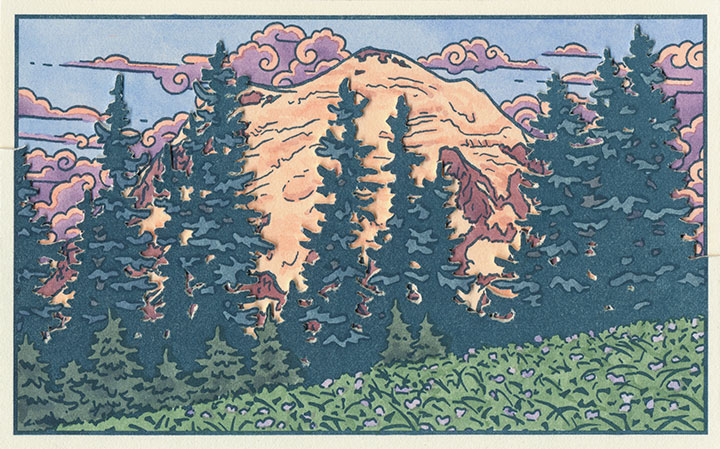

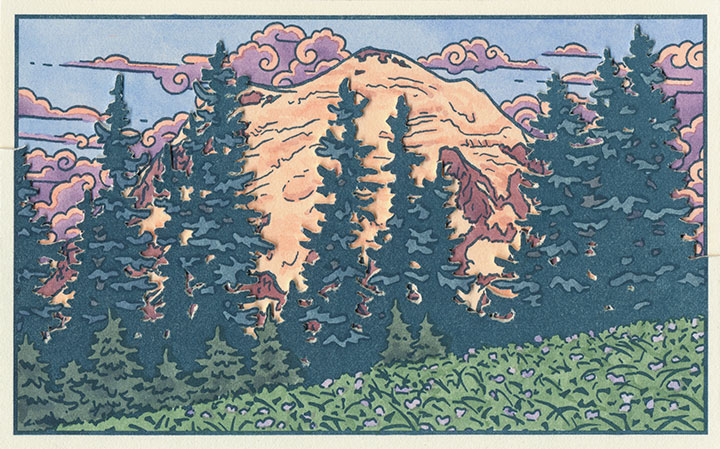

Part of what’s taking me so long is that at the same time, I’m working on a small series (like a baker’s dozen or so) of individual prints of images from the book (exhibit A above). There’s not a whole heap of rhyme or reason as to which illustrations I’ve chosen, except that these are some of my favorites. I’ll be posting them in the shop (believe me, they’ll be a lot more affordable than the book) as I finish them.

In the meantime, it’s time to light a few more lights, and keep the dark at bay so I can see what I’m doing.

Which reminds me—Happy Hanukkah!

November 17th, 2010

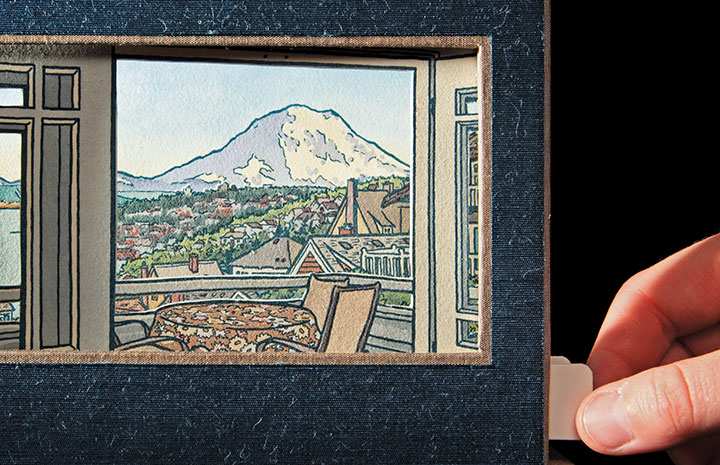

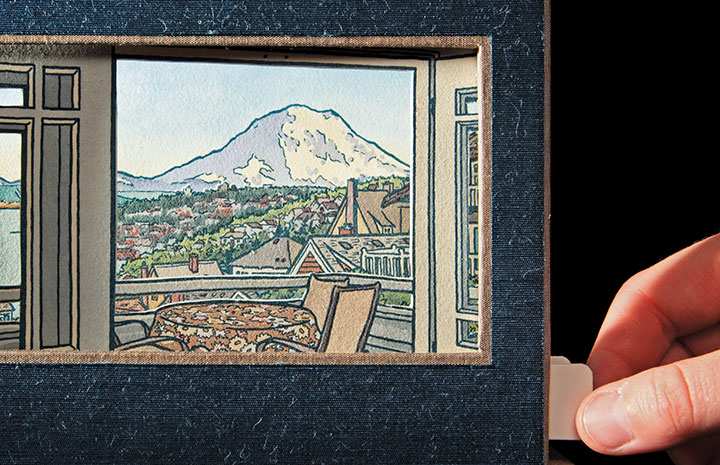

I’ve been hemming and hawing about how best to share this thing with you. Even with Sarah’s excellent photography, it’s just a lot more difficult to explain how it works when I can’t hold the book out into space and demonstrate in real time. It’s a problem with every artist book out there—an interactive sculpture, complete with moving parts, that also happens to tell a story is just dern hard to document.

So for now, I’m going to go through the mechanics of the thing, step by step, and go into the whys and wherefores in other posts. And for those of you who might not be familiar with the term artist book, you’re going to find out really quickly that this isn’t your basic hardcover book. The definition of “artist book” is way too broad to go into within this post (click the above link to go to what I wrote on my F.A.Q. about it), but I’m hoping that by the time you get to the bottom of this post, you’ll have an idea of just how broad the term can be—and what crazy things can happily fall into the category.

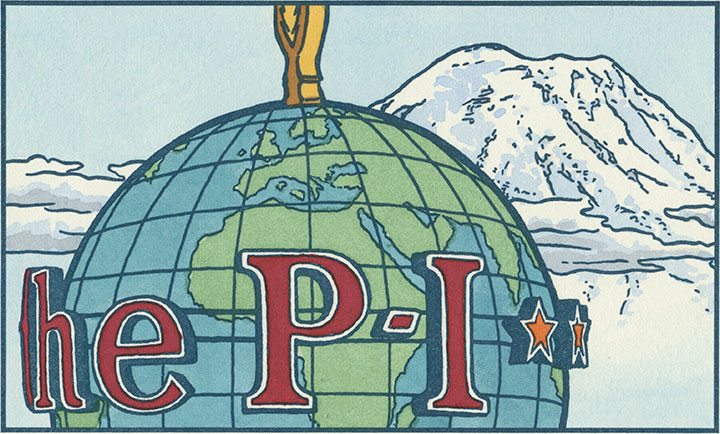

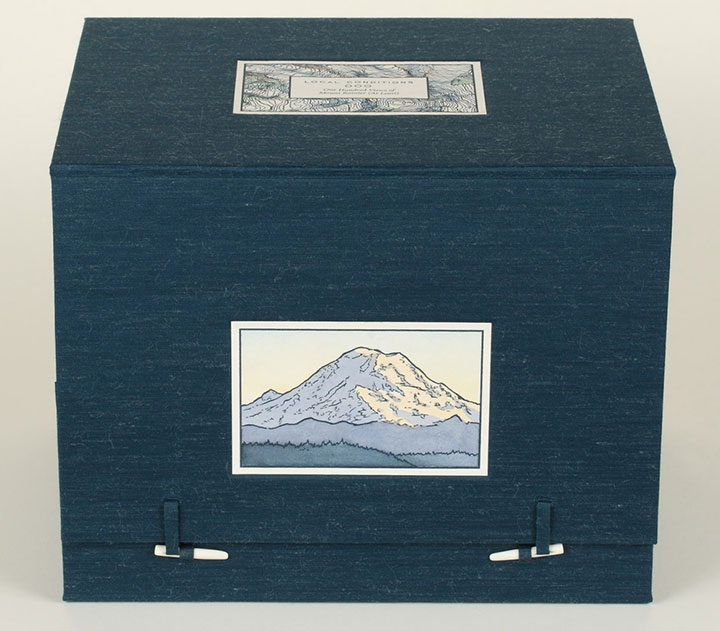

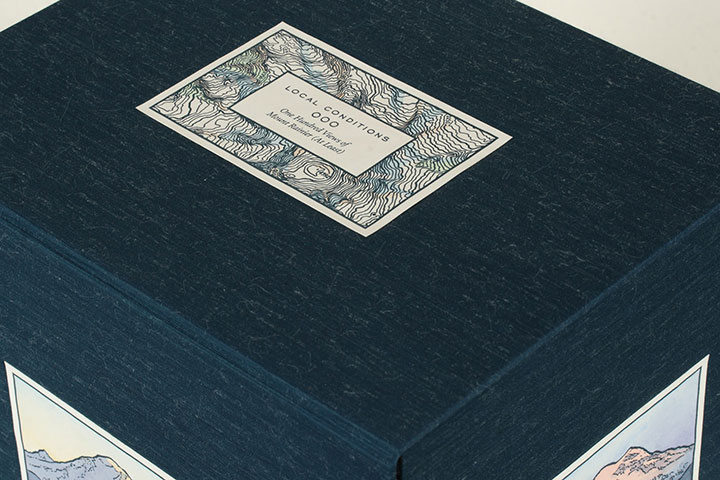

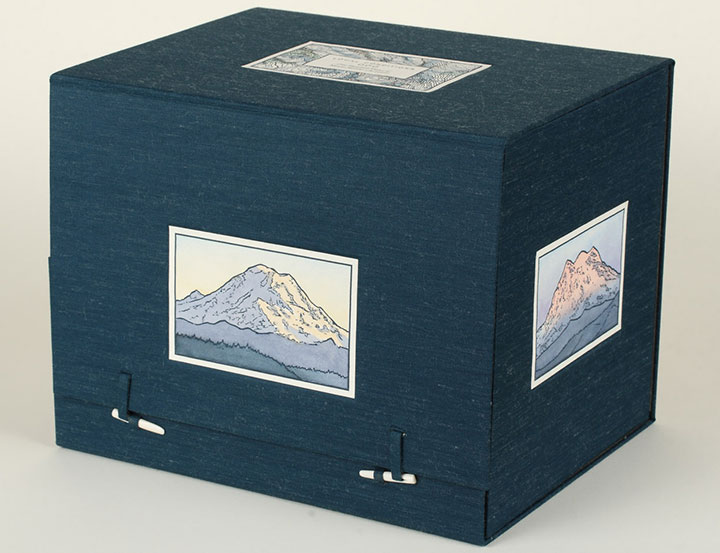

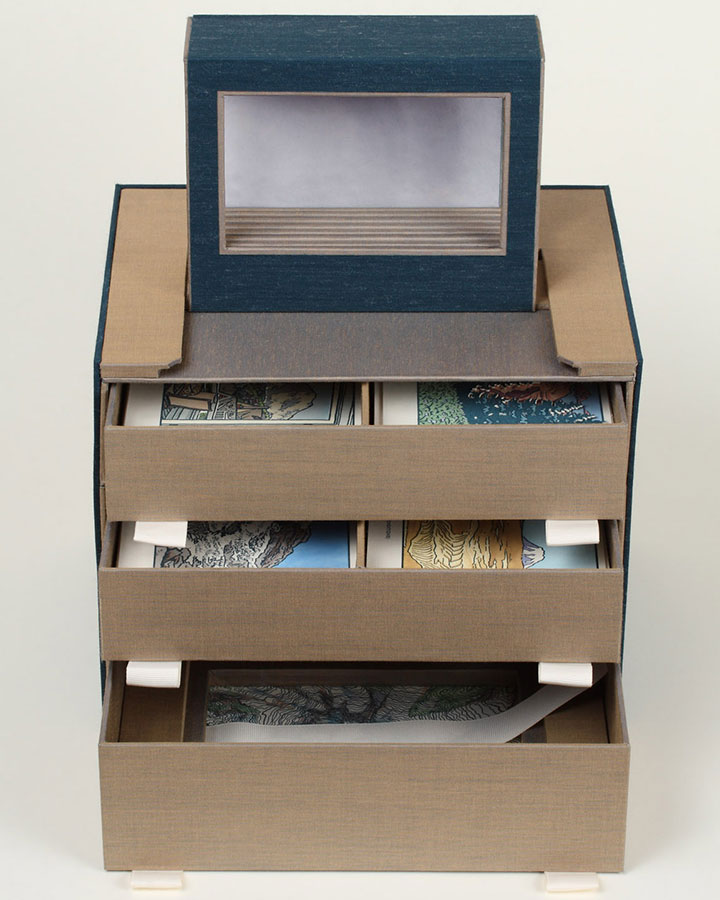

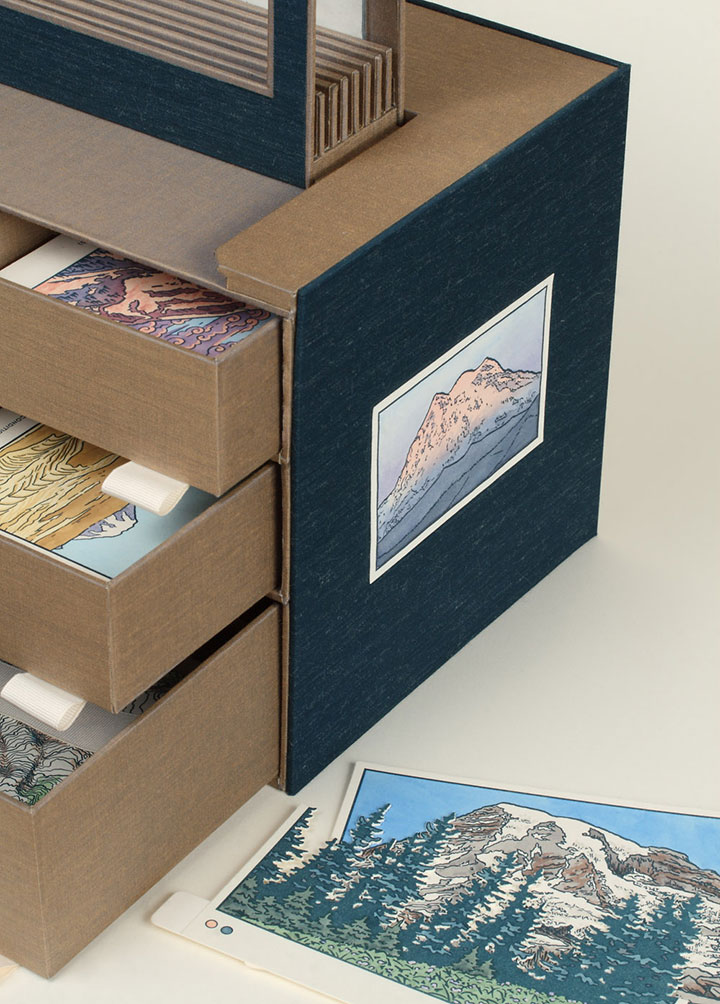

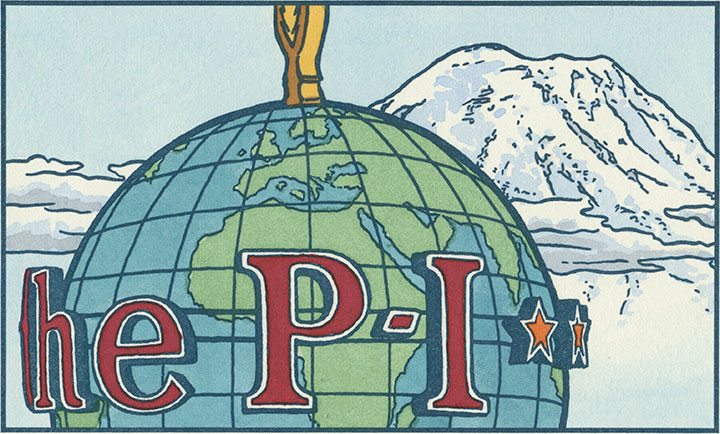

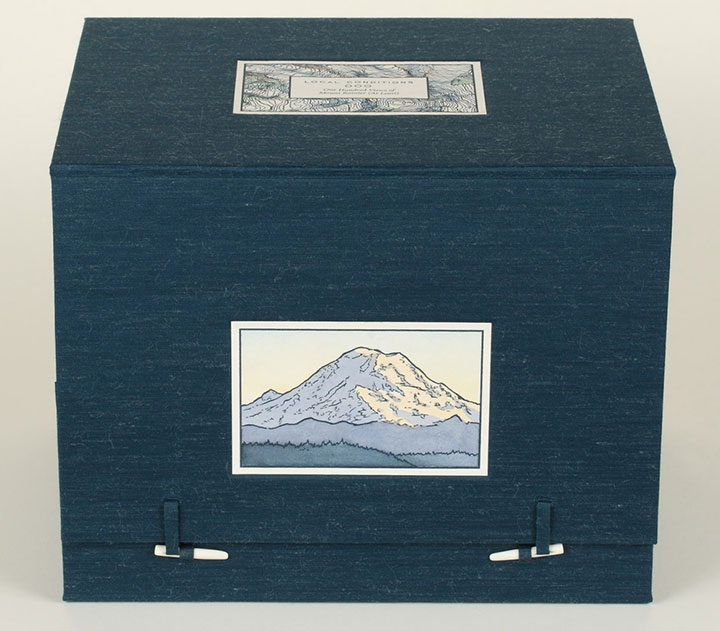

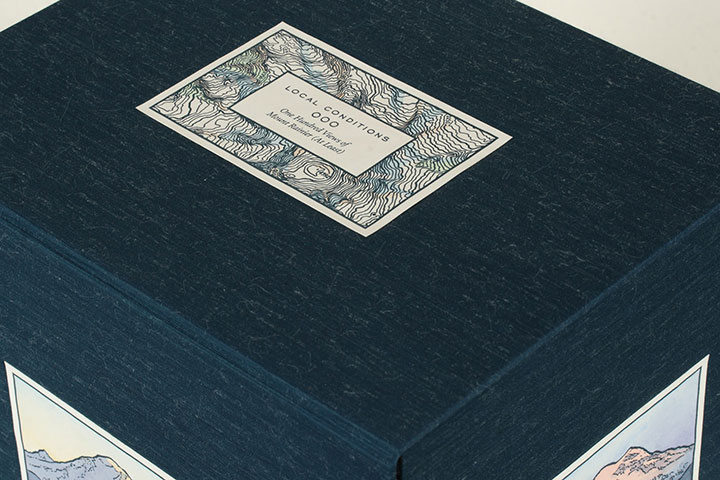

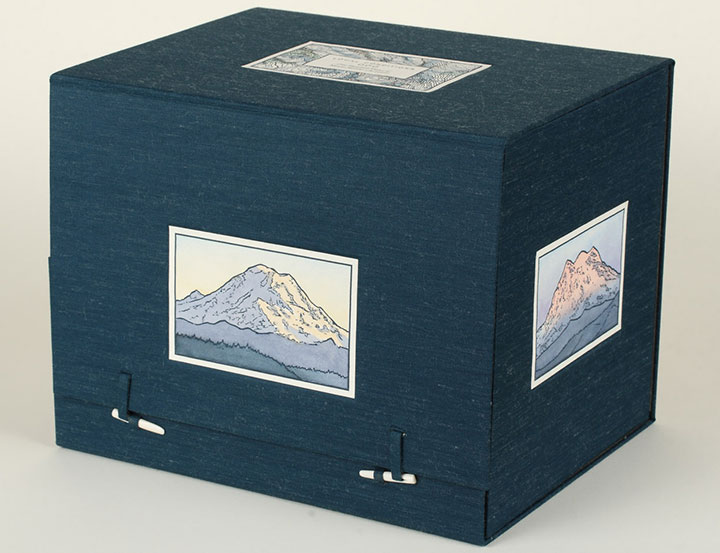

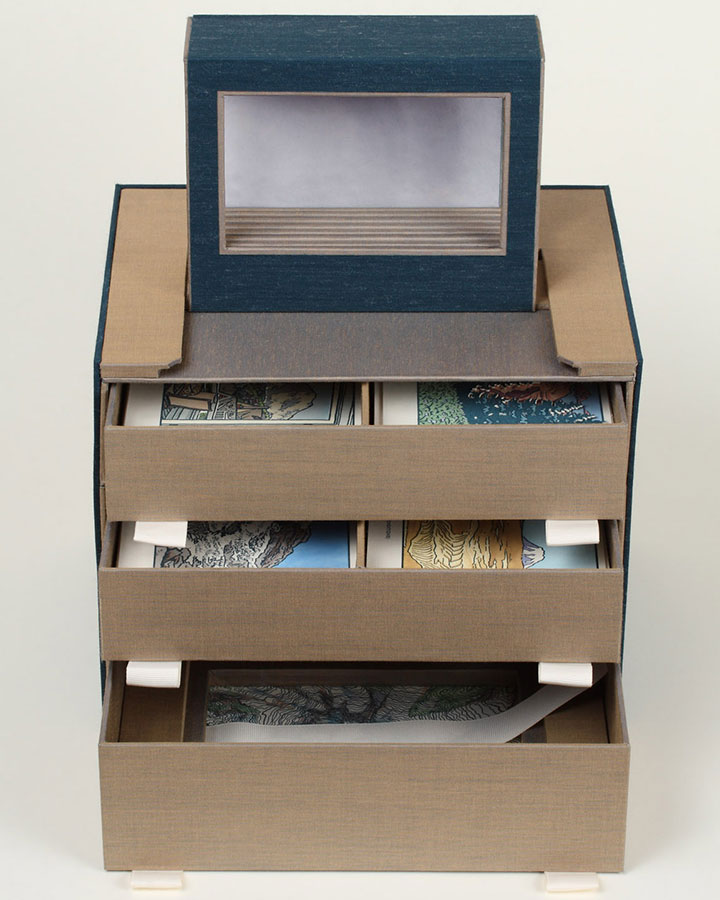

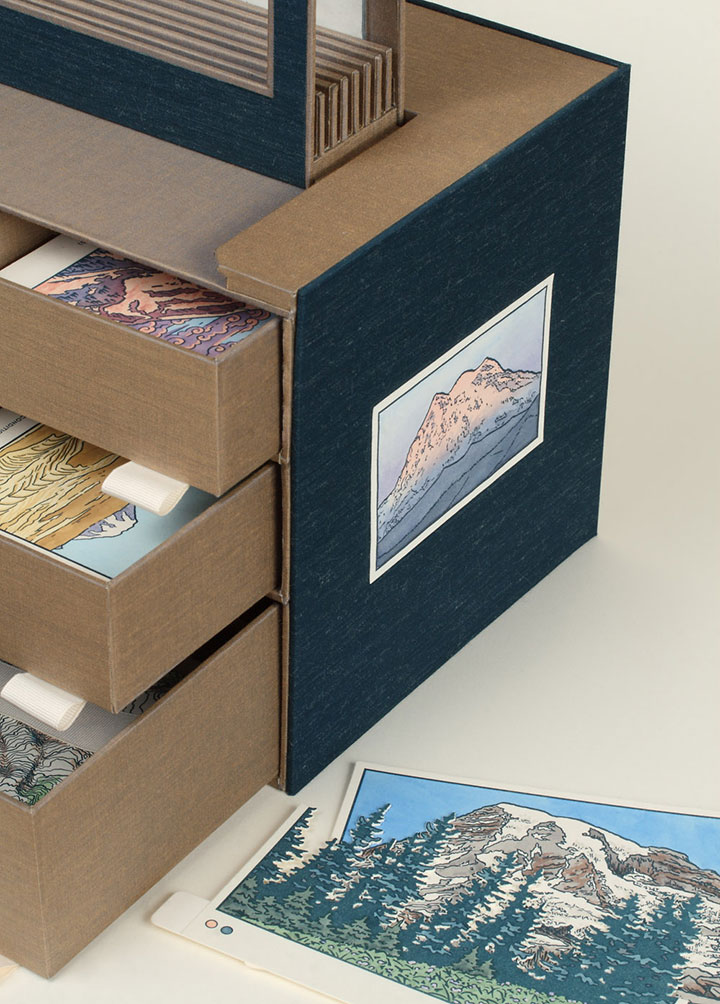

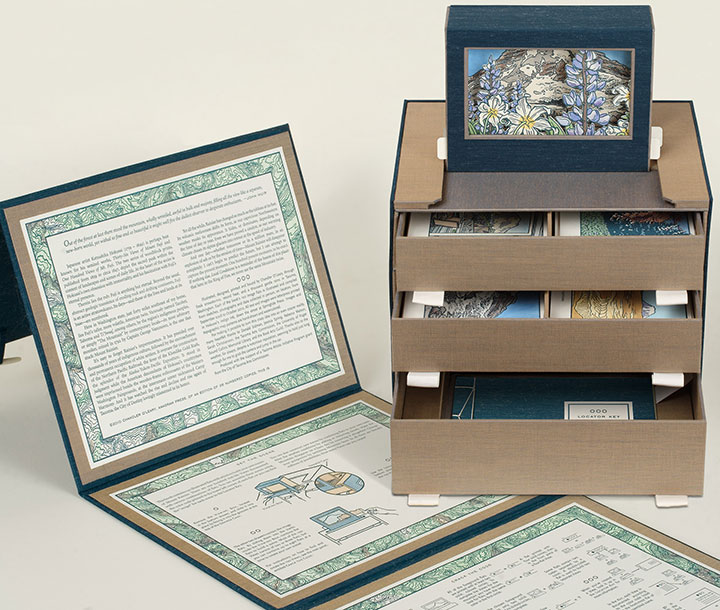

Okay, let’s start with the box. When it’s all closed up, Local Conditions is almost a cube (a 10-inch cube that’s heavy enough to be hiding a sack or two of flour inside). On the topmost face of the box is the frontispiece, containing the title and a topographic map illustration of the summit of Mt. Rainier.

The north, south, east and west sides of the box are faced with illustrations of the corresponding faces of Rainier, each depicting the mountain at sunset.

(That’s the eastern face on the left, and the north face beside it.)

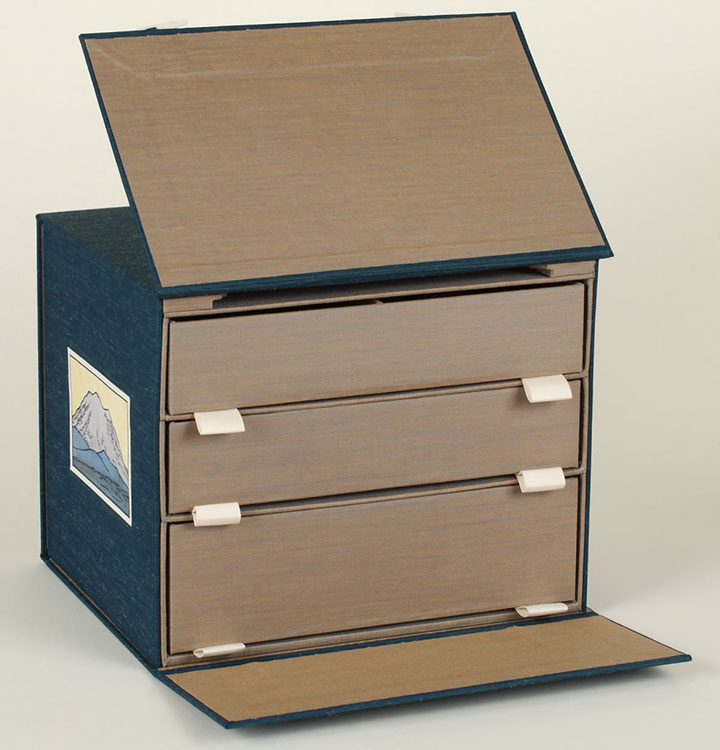

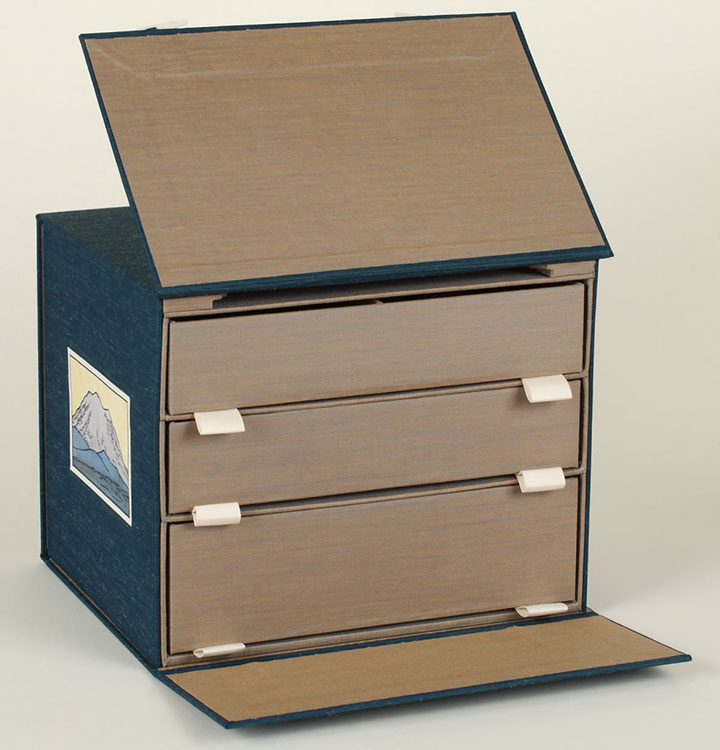

Now, those two little bone clasps hold the thing together, and when you flick them out of their loops,

the book opens up, revealing a chest of drawers. Keep pulling on the flap you just raised,

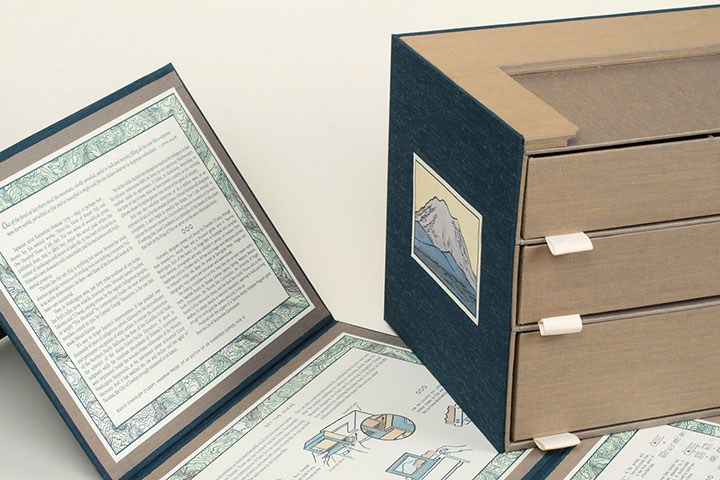

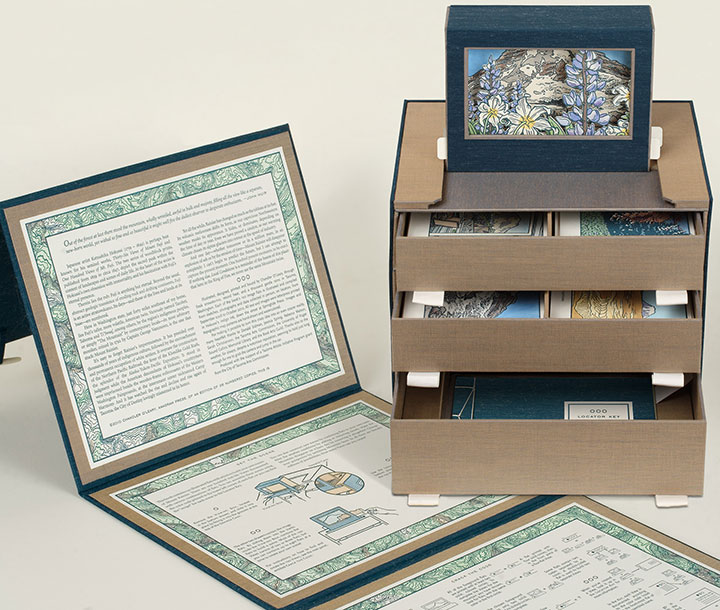

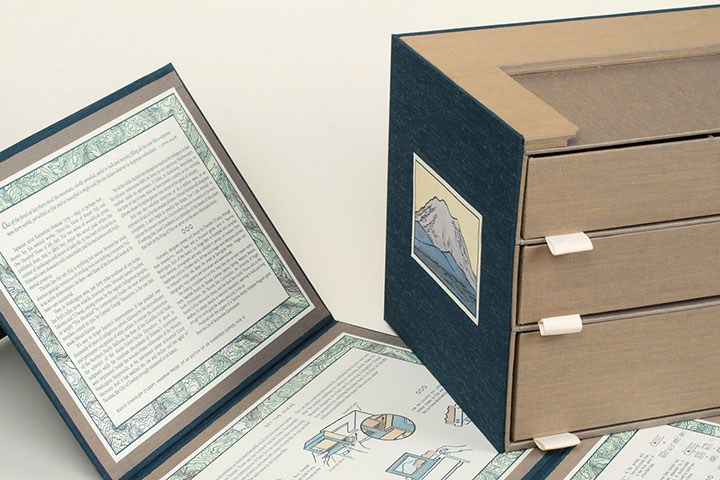

and you’ll find that you can take the whole outer wrapper off and read the colophon (see below) printed on the inside.

The other panels on the wrapper include detailed instructions on everything the book does.

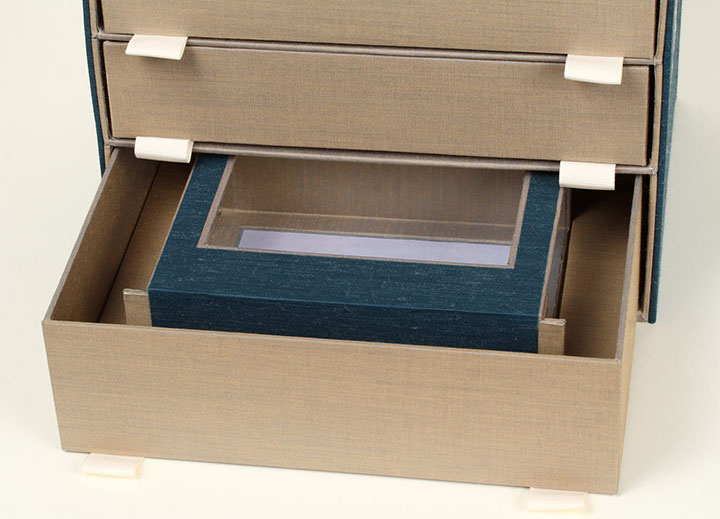

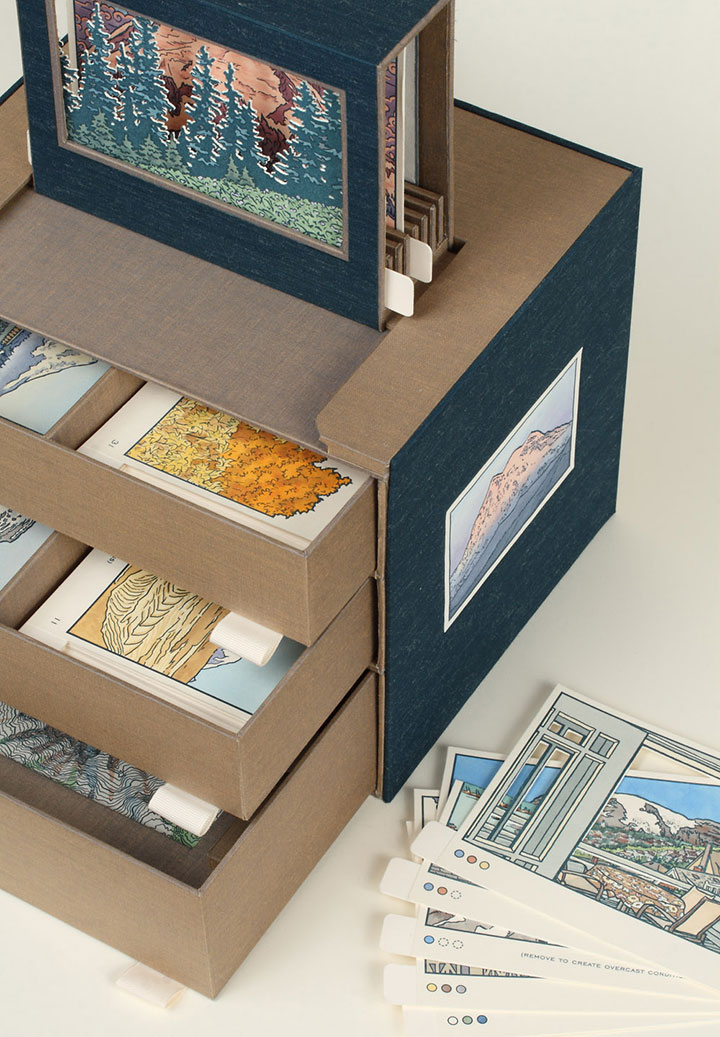

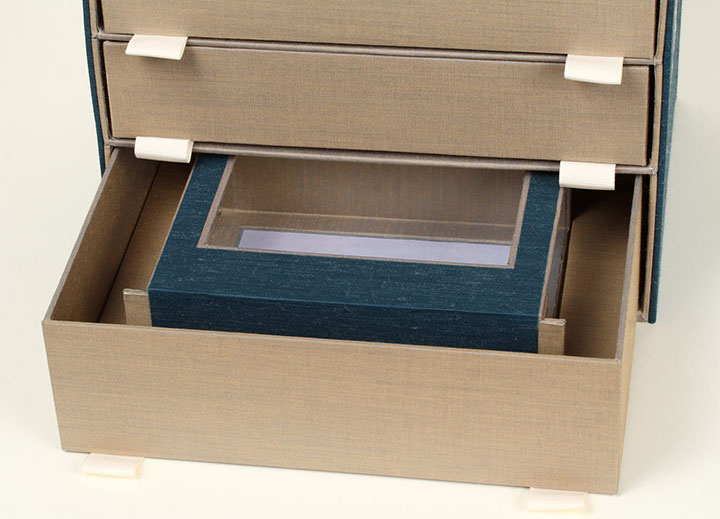

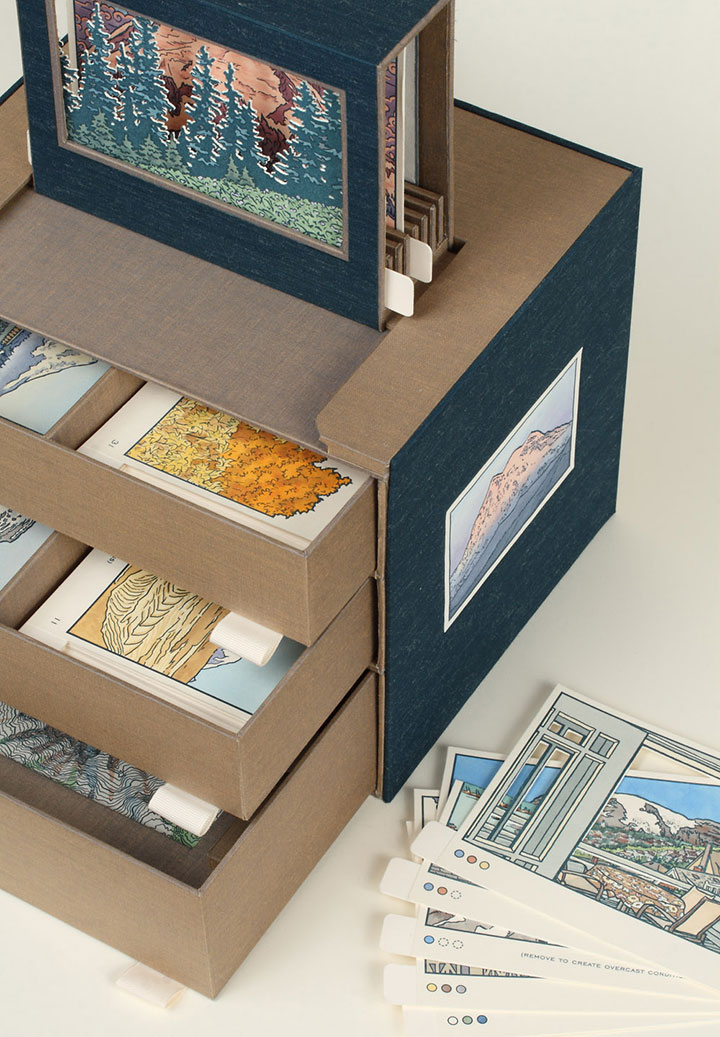

Next, let’s open the drawers—nested in the bottom one you’ll find a Viewing Box (yeah, I know … a box, within a box, within a box … sorry.) that consists of a window, a background panel, and two tabs that stick out from either side.

The tabs match up with the grooved unit at the top of the chest of drawers, and the Viewing Box slides into place.

So now the box is fully expanded, and the book is assembled for use. Now comes the fun part.

Take a closer look at the Viewing Box, and open the top two drawers.

Inside the drawers you’ll find a series of cut-out cards, each printed with a different image. These little image flats slide right into the slots of the Viewing Box,

and face out the window to form an instant picture—kind of like an old-fashioned stage set.

Now here’s the thing:

There are 120 flats to choose from. One hundred and twenty. Each one hand-printed, hand-painted, hand-cut.

By combining, layering and switching the flats in and out of the Viewing Box, you can create seemingly endless scenes of Mt Rainier. I came up with one hundred, and documented them as part of the book (again, I’ll elaborate later), but I’m more interested in how many you can dream up.

(Hint: a lot. Thousands. Millions. To be precise, 1.4 x 1015, or 1.4 quintillion, if you really wanted to push the envelope.)

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Local Conditions: One Hundred Views of Mt. Rainier (At Least)

Edition size: 26 numbered books and 5 roman-numeraled artist proofs

Book size: 10 x 8 x 8 inches when closed

Viewing window: 3 x 5 inches

Artist book consisting of viewing box and 120 image flats, illustrated and compiled from data collected in person, on location, over the course of two years. Housed in a set of drawers with nested stab-bound book and Japanese-style outer wrapper. Images and maps are hand-drawn, letterpress printed and individually hand-painted with watercolor. All image flats are hand-cut.

For price/purchase info, please contact me.

Edited to add (November 2011): As a supplement to the artist book, I also created a suite of 15 limited-edition letterpress prints, featuring some of my favorite scenes from the book. Just like the flats in the book, each print is letterpress printed and hand-painted with watercolor. You can find all 15 prints in the shop.

Colophon reads:

Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1759 – 1849) is perhaps best known for his seminal works, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji and One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. The two series of woodblock prints, published from 1829 to circa 1847, depict the sacred peak within the context of landscapes and scenes of daily life. At the heart of the series is Hokusai’s own obsession with immortality, and his fascination with Fuji’s eternal presence.

Therein lies the rub: Fuji is anything but eternal. Beyond the usual, abstract geologic transience of eroding rock and drifting continents, Fuji is an active stratovolcano. Its days—and those of the lives and lands at its base—are numbered.

Here in Washington state, just forty miles southeast of my home, lies Fuji’s taller, more volatile, American twin. Variously named Tacobet, Tahoma and Ti’Swaq’, among others, by the region’s indigenous peoples, or simply “The Mountain” by contemporary locals—its most arbitrary moniker, coined in 1792 by Captain George Vancouver, is the one that stuck: Mount Rainier.

It’s easy to forget Rainier’s impermanence. It has presided over thousands of years of indigenous culture, followed by the encroachment and permanent occupation of white settlers. It oversaw the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad, the fever of the Klondike Gold Rush, the splendor of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. It stood in judgment while the American descendants of Hokusai’s countrymen were imprisoned beside the wooden-frame rollercoaster of the Western Washington Fairgrounds, at the internment center nicknamed Camp Harmony. And it has watched the rise and decline and rise again of Tacoma, the City of Destiny lovingly misnamed in its honor.

Yet all the while, Rainier has changed as much as the tableau at its feet. Its volcanic restlessness shifts its form, as our capricious Northwestern weather masks its appearance. It hides, or dominates, depending on the time of day or year. Even we have proved a catalyst, as our warming climate chases its alpine glaciers into retreat at the speed of industry.

And one day—whether tomorrow or in a million years, in an explosion of ash or by the erosion of time—Mount Rainier will disappear completely. I can’t begin to predict the future, but I can attempt to capture the present moment. One hundred present moments, to be exact. If nothing else, Local Conditions is a reminder of the lesson of this place: that here in the Ring of Fire, we never see the same Mountain twice.

* * *

Illustrated, designed, printed and bound by Chandler O’Leary, through freak snowstorms, record heat, and a thousand gentle rains in Tacoma, Washington. Each of the book’s 120 image flats is illustrated and compiled from sketches, photographs and data collected in person, on location, from September 2008 to October 2010. All text and images were letterpress printed in Hokusai’s indigo ink, down the street at Springtide Press. Images and topographic map patterns are hand-drawn and watercolored.

For making it possible to turn this crazy idea into an even crazier reality, many heartfelt thanks to Jessica Spring, Sarah Christianson, the Tacoma Arts Commission, the University of Puget Sound Collins Memorial Library, and the Book Arts Guild. Thanks also to the weather, for always, despite a notorious reputation, seeming to hold just long enough for me to grab the camera and jump in the car.

Produced with the support of a Tacoma Artists Initiative Program grant from the City of Tacoma Arts Commission.

November 14th, 2010

I know I’ve made quite a fuss over my new artist book, but while all my energy has gone into putting that one out into the world, one of my older books is also getting some more time in the limelight.

Photo by Nathaniel Willson

This fall you can find The Faery Gardener on display in Seattle, along with many other contemporary artist books by Northwestern printmakers, designers, illustrators and binders.

Hand2Hand: The Book as Art

Exhibit runs through January 9

Columbia City Gallery

4864 Rainier Ave. South, Seattle

When I first started making artist books, you would have been hard-pressed to find a gallery show centered on the subject. Now this sort of exhibit is everywhere—I mean, I’m just one artist, and I’ve been in several this year alone! It seems like the book arts are just another, well-accepted part of the fine arts—and that’s what I’ve been hoping for, all along.

November 5th, 2010

Photos by Sarah Christianson

The show is all set up,

and the book is officially out in the world.

Many thanks to the enormous crowd of folks who descended upon the opening last night—and to my amazing friend Sarah Christianson for providing every kind of emotional and practical support I can think of.

October 22nd, 2010

It’s getting harder and harder to keep the secret these days—the Rainier book is almost done, and I’m just dying to show you. But I don’t want to ruin the surprise for T-town, so I’m going to keep it under my hat for just a little longer. But after over two years of being under wraps, the book is gussying it up and stepping out for a solo exhibition. Here’s a brief description of what you’ll see:

Local Conditions, an interactive artist book, captures the changing faces of Mt. Rainier. Explore the 100 Views—or create one of your own—to discover a mountain both immortal and impermanent.

The book contains 120 image flats and a viewing box; by combining and layering the flats, the reader can create literally millions of scenes. Images are illustrated and compiled from data collected in person, on location, over the course of two years. Letterpress printed, watercolored, and hand-bound in an edition of 26 books. Sponsored by the Tacoma Arts Commission.

Exhibit runs November 4 through January 21

Collins Memorial Library, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA

Opening reception: Thursday, November 4, 4:30 to 6:30 p.m.

Artist talk (sponsored by the Book Arts Guild): Thursday, November 11, 7 p.m., Room 020

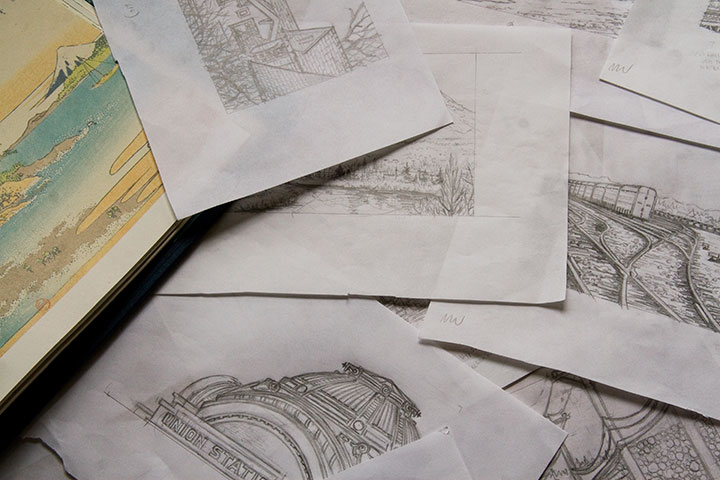

Photo by Sarah Christianson

If you miss the exhibition opening, I’ll have some of the process materials from the book out for perusal at this year’s Studio Tour—as well as the brand new Dead Feminist broadside! (Look for it online in early November.) So be sure to stop by!

Saturday and Sunday, November 6 and 7

Open 10 am to 4 pm.

More information, maps, addresses and directions can be found here.

See you then!

October 16th, 2010

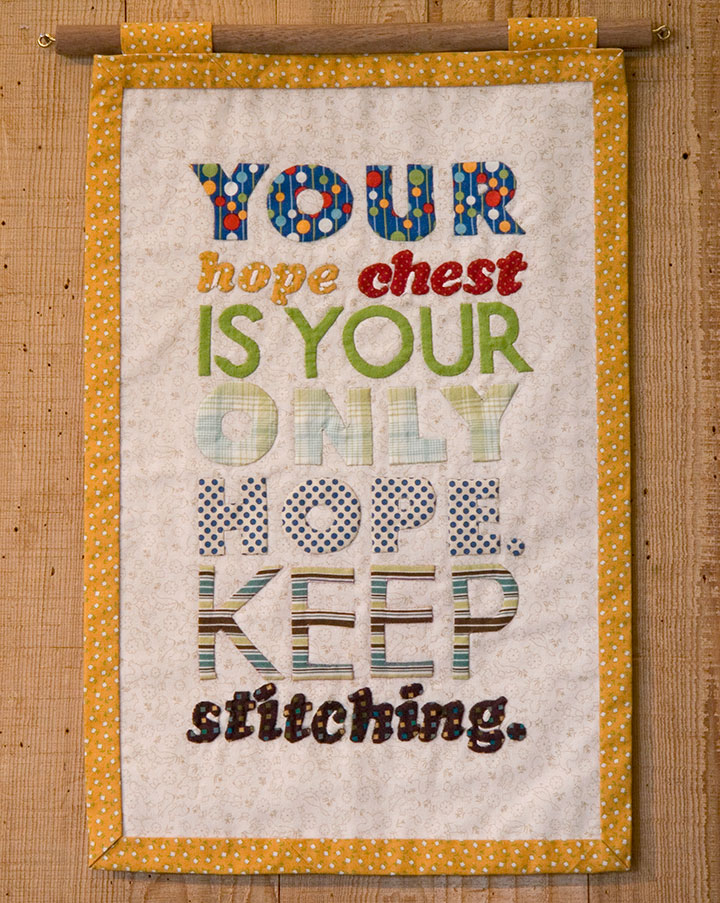

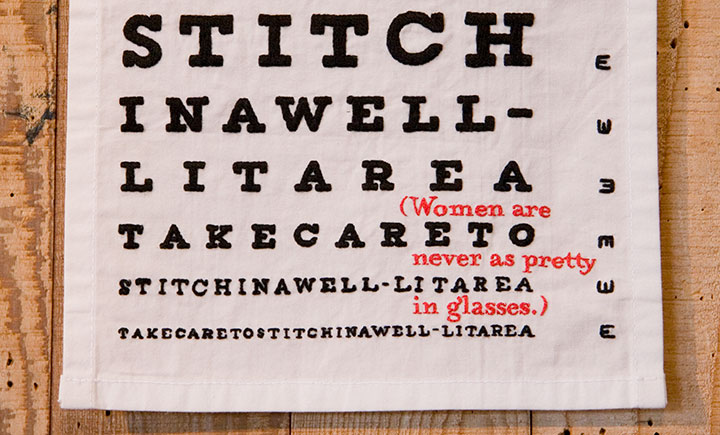

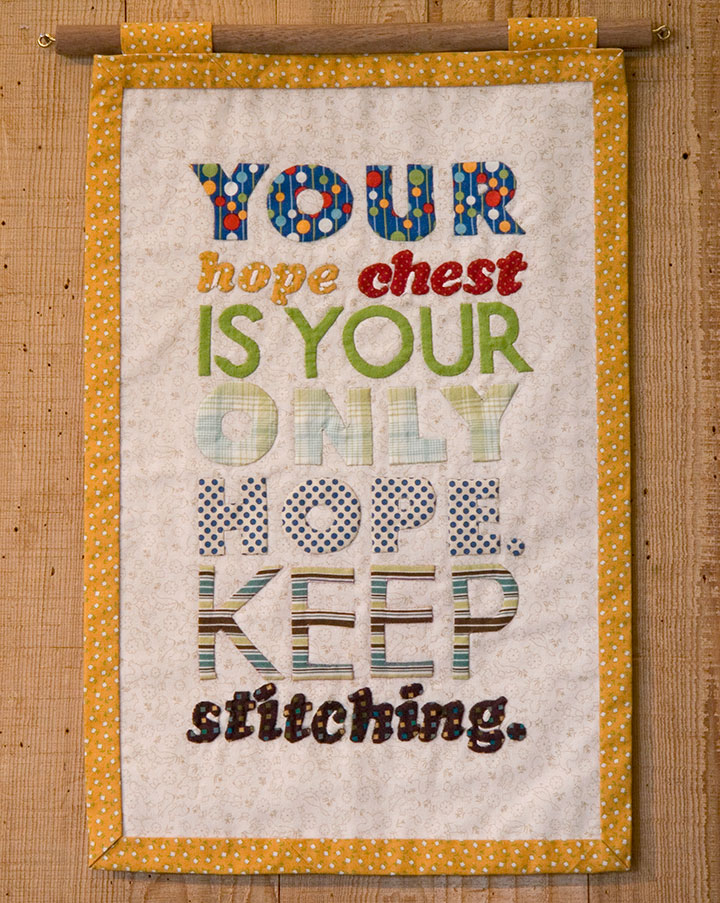

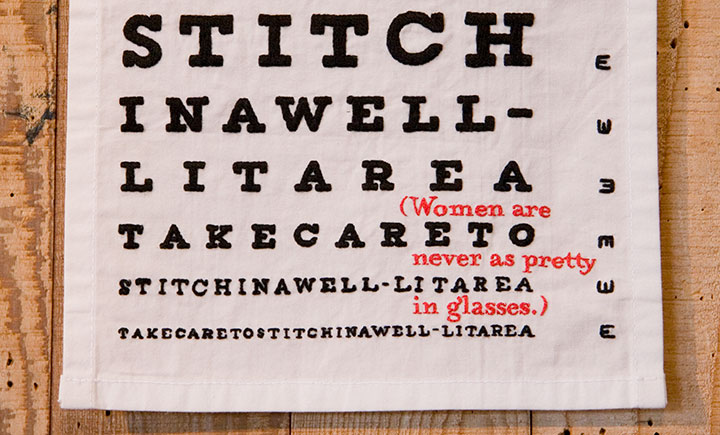

By now you’ve figured out that I have a thing for stitched lettering; and since I’ve already rambled on ad nauseum in the last post, I can keep this one a little shorter.

And anyway, I somehow neglected to take any process photos for two of these. Oops.

The knitted broadside was such a success that I decided to try branching out into other textile media. For Broadside No. 4, I took a shot at appliqué—something I’d never done before. Hand-sewing all those fiddly little pieces of fabric ended up being just as daunting as cutting a steek.

The hard work was oddly fitting for the concept: historically, a traditional wedding trousseau would have been sewn by a girl or young woman, in hopes of one day becoming a married woman with a home of her own. By the time she reached young adulthood, a woman would have spent years creating dozens of hand-sewn garments, household linens and other useful textiles, all gathered and stored in her “hope chest,” awaiting the day she would become a bride.

The thing is, back in the days when women couldn’t vote, or own property, or head a household, marriage was a woman’s only shot at independence or social status. (Hence the snark.)

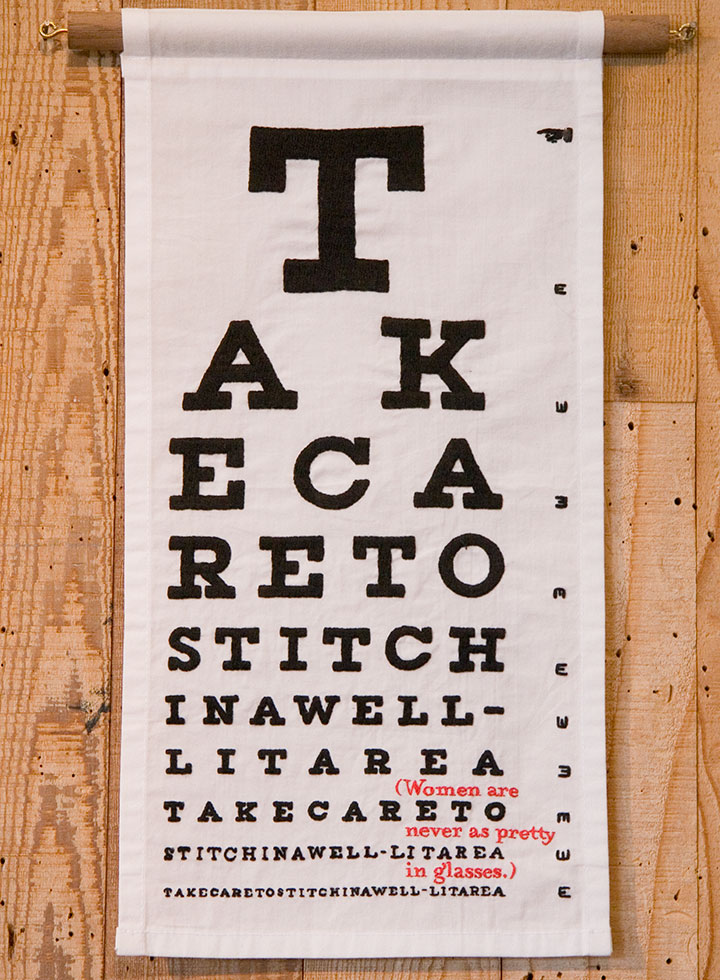

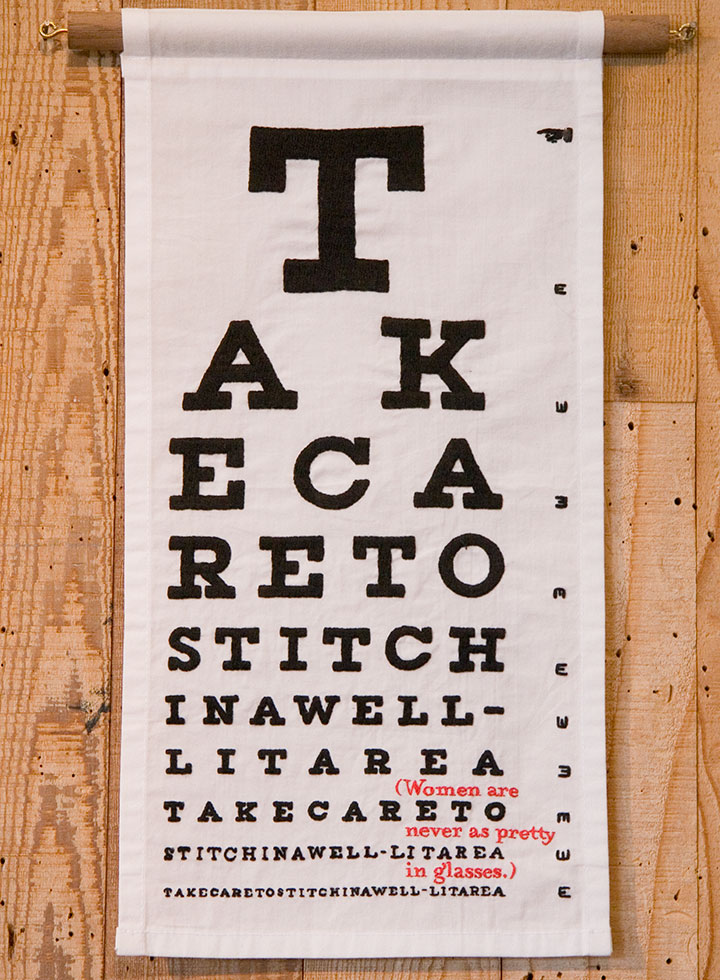

For the others, I turned to the original, old-school ancestor of fabric paint: embroidery. The method fit the madness this time, too, as I spent what seemed like a century hunched over and squinting, hand-stitching an eye chart…

…complete with something to read between the lines.

This one gets personal. As a glasses-wearing gal myself, I happen to disagree with the statement—but I’ve actually heard these very words spoken by a woman. She wasn’t wearing glasses.

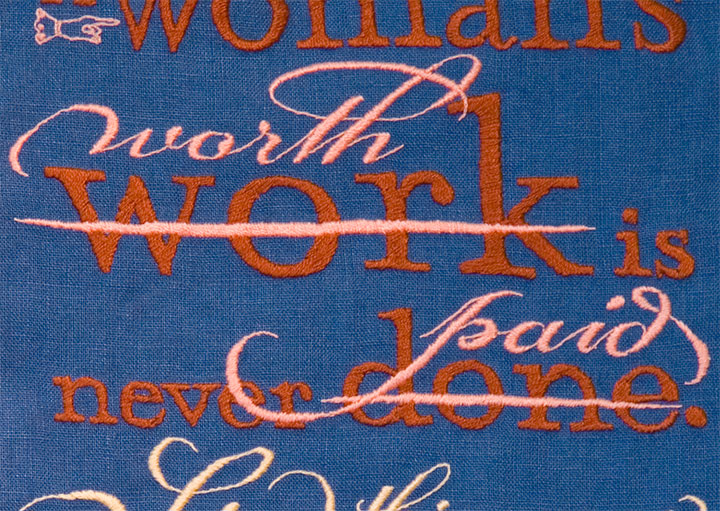

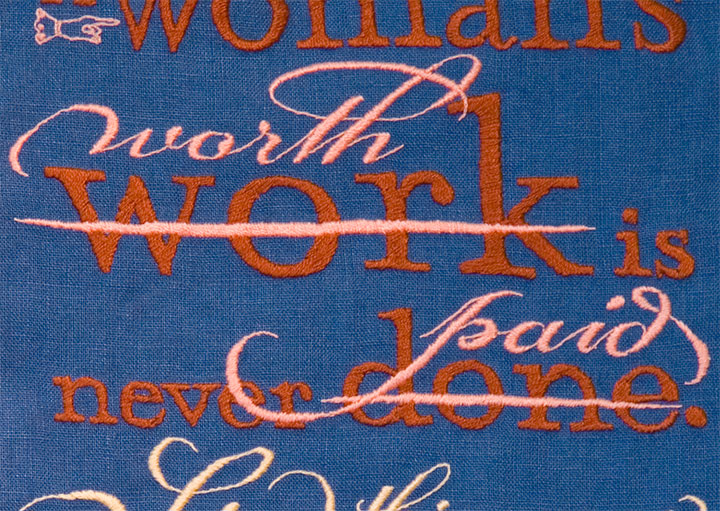

Last of all, I got to thinking about how men who sew for a living are called tailors—and women who do the same are called seamstresses. And how the two terms don’t quite add up to the same meaning.

Despite what the scornful quipping of the text might indicate, I had the most gleeful fun with this one. Unlike knitting, which confines the designer to a grid, or appliqué, which can only push the detailing so far, embroidery has almost limitless possibilities. So I went nuts with the tails and ligatures and dingbats, simply because I could. I love that about embroidery—it’s as flexible as I need it to be, and as fluid and crisp as the printed page.

All that was required was the patience to work each letter by hand. But it didn’t feel like patience—it felt like meditation.

It’s surprising how easy it is for embroidery to mimic letterpress. And watching “wood” type pop up from the fabric, rather than punch into paper, is a mighty satisfying sight.

Uppity notions aside (no pun intended), the Women’s Work broadsides are a fun way to slow down and take a break from what I normally do in the studio. But as I wrap up each one, I find myself hankering to get back into the print shop. By comparison, setting type and drawing letters suddenly seems like speedy work!

October 11th, 2010

While I’ve been hiding away, wrangling my 900-pound gorilla, Jessica has been cooking up something pretty great.

Thanks to her hard work and the wonderful Brian Hutcheson‘s invitation, we are pleased as punch to announce our first-ever dual exhibition!

Feminist Wiles: Jessica Spring and Chandler O’Leary

Now through November 5

Ted Sanford Gallery, Charles Wright Academy

7723 Chambers Creek Rd. W

Tacoma, Washington

Open 8 to 5, Monday through Friday

It seems weird that after more than two years of collaborating, giving lectures and printing in the street, we’ve never had an honest-to-goodness show together.

But when Brian offered us a cavernous space, his help with installation, and the chance to indoctrinate the innocent introduce our series to the kids at Charles Wright—well, we’d be nuts to pass that up.

For the first time, all nine (and-a-half) Dead Feminist broadsides to date, plus our two steamroller gals, are on display together.

We also have a little mini-exhibit about our process,

and lots of little goodies to introduce people to letterpress.

Jessica and I have rounded out the collection with solo work that complements the theme of the show. Jessica’s half consists of Do You Feel Beautiful?, a series of broadsides featuring famous aphorisms on beauty. Here’s the thing that blows my mind into tiny pieces every time I think of it: the quotes are letterpress printed on the pages of a Braille edition of Seventeen magazine. Whoa.

I contributed Women’s Work, an ongoing series of broadsides created in hand-sewn textiles rather than my usual letterpress.

Now, I get a ton of questions about these things whenever I show them, so I thought I’d outline the ideas and process behind them here.

The Tailor first sparked the idea for the series; as you know, he makes his own clothing (hence the nickname). This is a feat that never ceases to amaze me, and I’m not the only one—he gets a lot of comments, usually along the lines of “Wow, you made that?” He’s always a little surprised by these comments, because where he grew up, a lot of people (including his family) wore homemade clothing. That got me thinking, though. The people who do all that sewing in the Tailor’s hometown are women—mothers, grandmothers, sisters, daughters, wives. We’re all surrounded and preceded by generations of women who sew clothing, or knit sweaters, or draft patterns from scratch, without any rave reviews—or any comment at all. But every male knitter or quilter I’ve known, every rare and wonderful man who ever picked up a needle, is either looked at like he’s nuts, or treated with reverent awe. It strikes me as a little strange that depending on who made it, and who’s looking at it, a pair of pants can be a work of art—and an actual work of art can be completely ignored.

If you go further back, like, I dunno, throughout the entirety of human history—you’ll find that both men and women have been responsible for creating textile goods in nearly every culture on earth. Yet in almost every case, when men made textiles it was as part of some sort of guild craft or other professional setting. When women made textiles, it was as part of the home front. This is true in every part of the globe, in pretty much every era, going back to the advent of textile technology.

No matter who does the stitching, there’s an enormous amount of technical skill and design sensibility required to make a garment or textile object. So instead of creating divisions and pigeonholes—instead of separating into Art and Not Art, into Man-made and Woman-made, what if we started seeing the inherent worth in the objects themselves? And what happens when we take a handmade textile and stick it in a gallery? Does its perception change?

Based on what I’ve seen so far with these broadsides, I’d say it does. It’s been an interesting experiment, for sure.

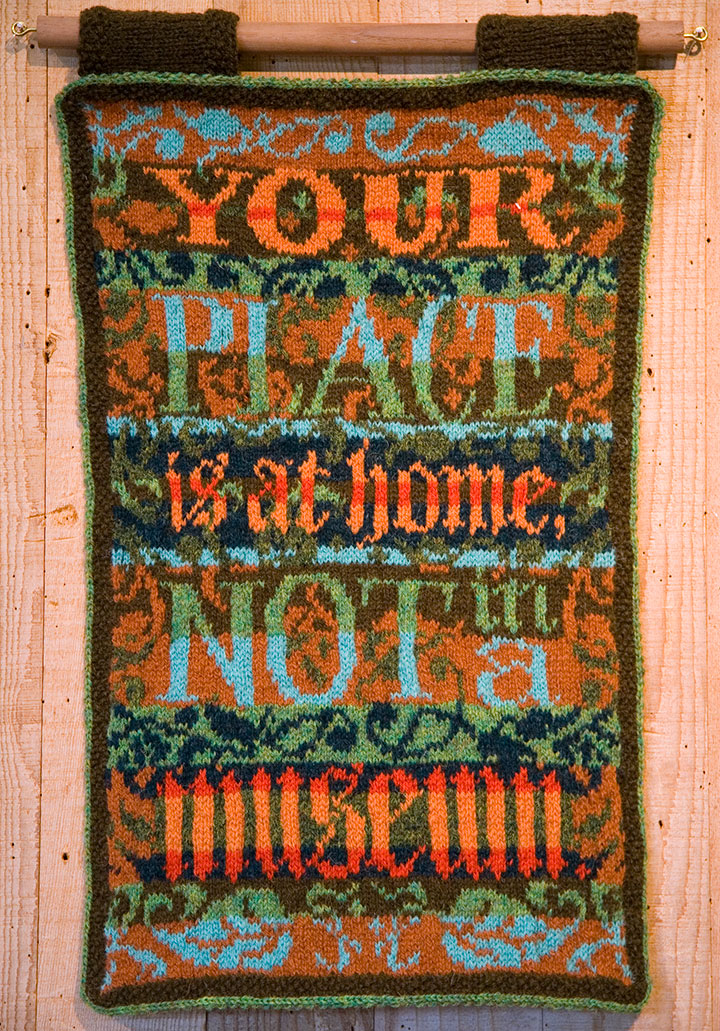

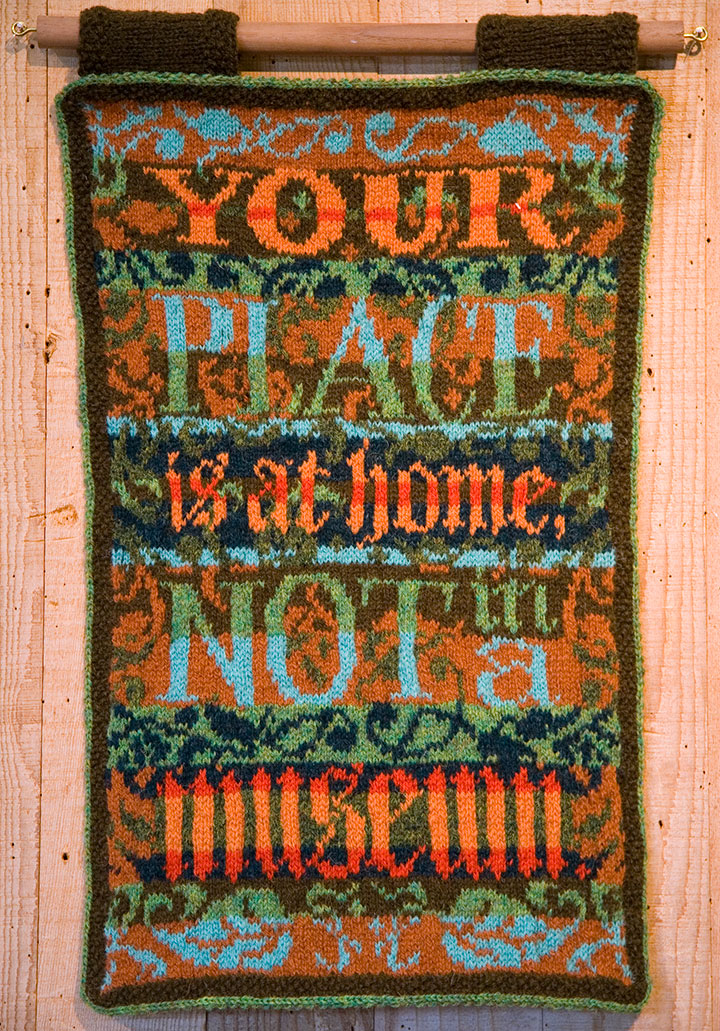

So the Women’s Work series is a bit of an indictment of the double standard, and while the snark is aimed at a wider target, I wrote them as if I were speaking to a woman. Each one is completely made/knitted/sewn/pieced/embroidered/etc. by hand, from design to pattern to construction. The text reads in the voice of a disapproving female role model (or the insidious voice inside our own heads)—in the tone of the backhanded compliment, the cheerful put-down. Each is also designed in the style of a traditional letterpress broadside, to put the typography within the context of an art form centered around mass communication.

This guy requires a little more of an explanation for folks who aren’t already into wool.

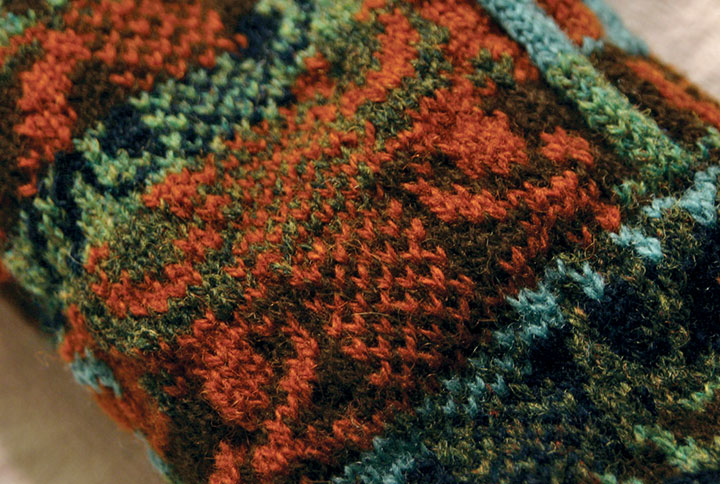

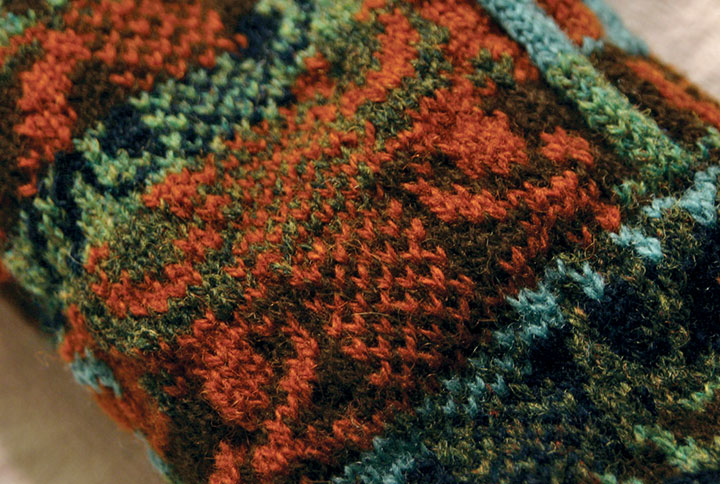

This piece, made almost three years ago now, is hand-knitted with Shetland wool, using the traditional Fair Isle knitting technique. Fair Isle—a method practiced since the nineteenth century on the tiny island of the same name, halfway between Scotland and Norway—is a tricky, rather ingenious thing. Traditional Fair Isle pieces are knit with two colors of yarn at the same time; the resulting fabric is durable, extremely warm, and great for any chilly, foggy, wet climate (like, hello, here). Beyond its über-practicality, Fair Isle knitting is simply gorgeous (take a gander at Google). By nature the double-thick fabric is dense and flat, making it an ideal ground for complex patterns and designs—it’s the perfect mix of function and fancy.

Here’s how it works: even though the piece is knitted with two different colors of yarn at once, only one strand at a time ever passes through the needles. The unused strand of yarn is carried loosely, or “floated,” behind the work—which creates a reversed-out image of the design on the back of the piece. It’s the floats that give structure to the fabric, and make it so cozy-warm.

If you were to create a plain ol’ piece of ordinary knitting, you’d proceed from one end to the other of a row, flip the piece over, and work back the other direction. Rinse and repeat. If you tried that with a piece of Fair Isle knitting, working the “wrong” side would be extremely difficult, since the floats would now be facing you and covering your stitches. Now comes the tricky, smarty-pants part. Flat Fair Isle pieces are first knitted up into a big round tube, and then cut to lie flat. When you knit in the round, you never encounter the wrong side of the work. You just spiral around and around on the right side, happily knitting away and floating the unused color behind you as you go.

So in this case, once I had drafted my design into a gridded stitch pattern, I just pretended I was knitting one really big sleeve (or a neck warmer for a giraffe) with really teeny needles.

Ah, but remember the operative words above: you have to cut the piece to finish it. I had never done this before, and let me tell you, there’s an awful, terrifying finality to the idea. Torn sweaters unravel. Snagged socks fall apart. Who in their right mind would cut a piece of knitting on purpose? And even if you could do it, what happens if you make a mistake? Once you make that cut, you’re done.

This is where the true brilliance of the technique hit me like a ton of bricks. The Scotswomen of Fair Isle are a breed apart—and so are their sheep. Shetland wool, the material traditionally used in Fair Isle knitting, has a magical property that makes this crazy notion work: each wool fiber is covered with microscopic scales that attach to one another. Because the wool sticks to itself, the stitches become slightly matted as you knit. So following the Fair Isle method, you work a little buffer zone called a steek (see the checkerboard strip above?) into your design, and then cut right down the center of the steek. If you use trusty Shetland wool, your stitches won’t unravel when you cut them.

At least, that was the theory. I didn’t quite believe it at the time. But I’d come this far—I didn’t want to lose faith. (If you’re looking to try Fair Isle knitting yourself, I find a glass of wine helps.) So I took a steadying swig, held my breath, and cut.

And then I exhaled. And blinked. I had a flat piece. Gingerly I tested the cut edge—and was amazed. Even with a fair bit of tugging, the stitches refused to unravel.

I will never question a Scotswoman again.

My favorite thing about all of this, beyond the magic of Fair Isle itself, is that knitting really lends itself well to letterforms. Even though the pattern is drafted out on a grid, the forgiving nature of knitted stitches turns every square on the grid into a slightly curved, irregular shape. So when you zoom out and look at the piece from a distance, those grid “pixels” turn into nice little serifs, curves and curlicues.

The rest of the broadsides in the series are made using other types of needlework (more on that in the next post), but the knitted piece is still my favorite. I think I need another dose of that Fair Isle magic in my life—maybe next year you’ll find me up to my knees in wool again.

(Read about the rest of the “Women’s Work” broadsides in part two.)

September 15th, 2010

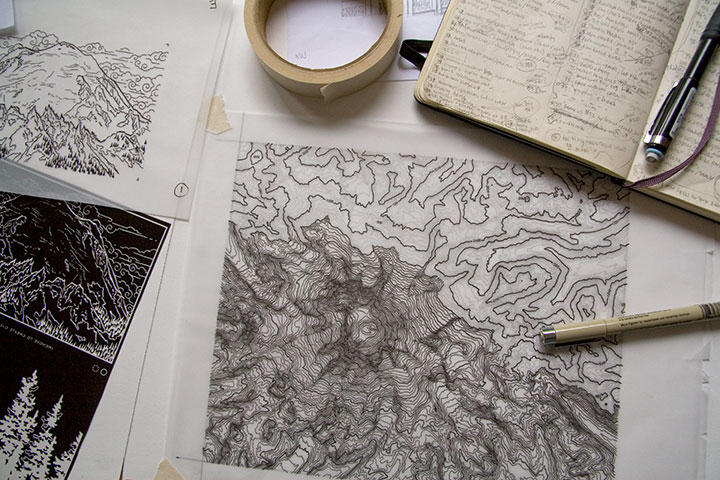

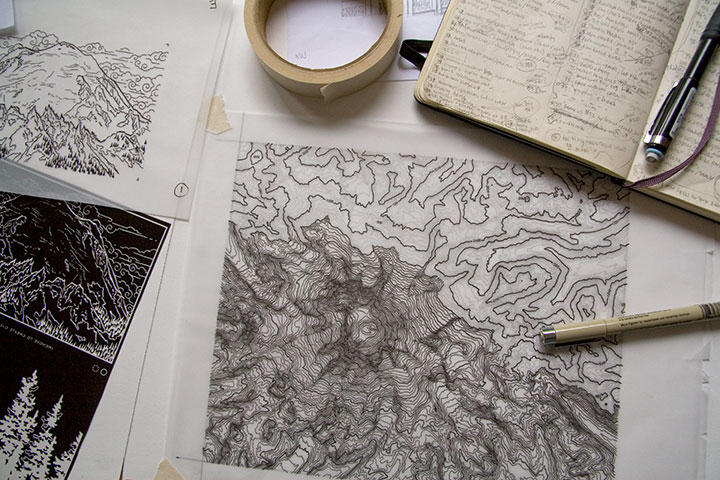

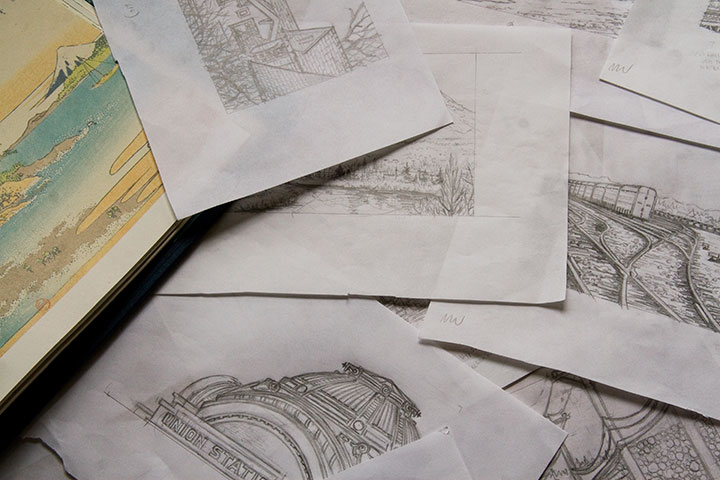

Lately I’ve spent nearly every waking minute of each day with my face an inch away from the drafting table.

Let’s step back, and stretch out a bit.

My studio is often a sea of papers—an occupational hazard—but these days the swells have consisted of pencil snapshots for my Mt. Rainier book. Dozens, and dozens, and dozens of them.

Time is ticking down, counting closer and closer to zero, and there are still many miles to cover before the clock strikes deadline. Yet suddenly, things are starting to come together. It won’t be long until I can share something that makes sense—something that looks more like a book, and less like a pile of drawings. I promise that you’ll be among the first to see it when I do.

But if I go missing for long stretches at a time—well, you know where to find me.

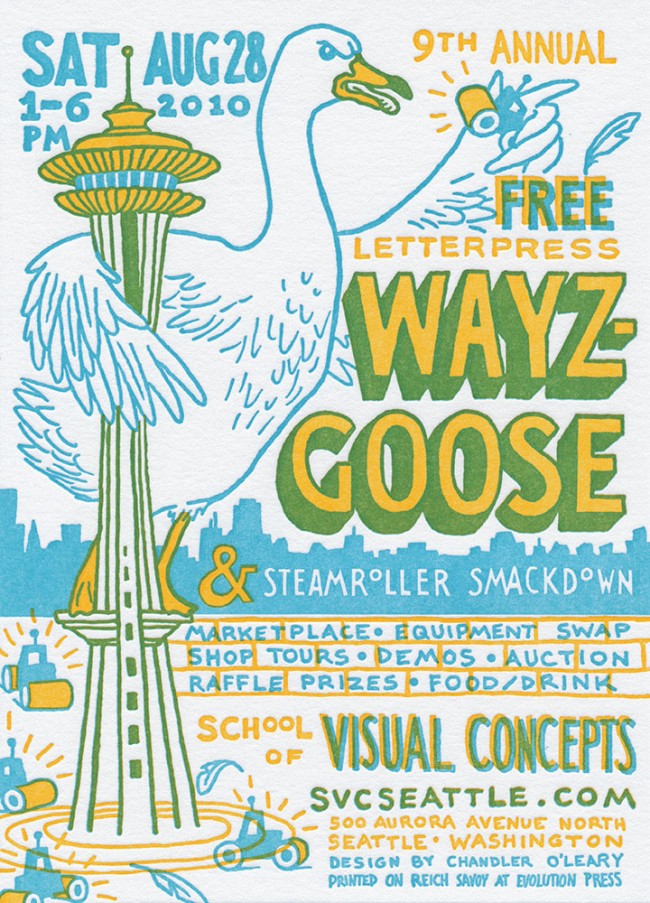

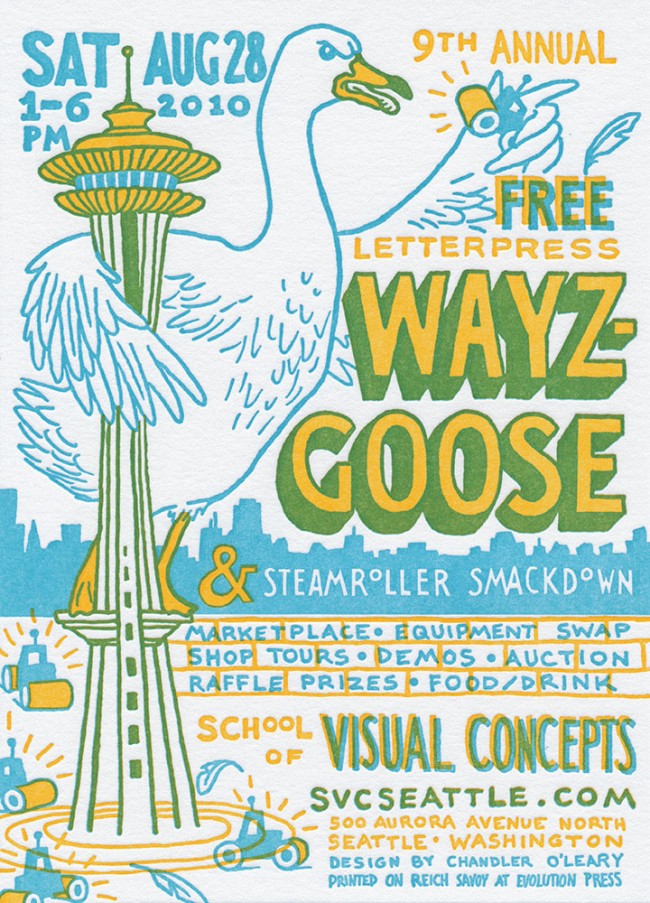

August 25th, 2010

Jessica and I are waist-deep in the new Dead Feminist print (look for it here next week), so I’m just popping in to wave hello—and to warn you, in badly-dubbed English, about the giant goose climbing the Space Needle.

Just kidding … but they will be sending in the steamrollers. This Saturday, in the Needle’s mighty shadow, is Seattle’s biggest letterpress party of the year: Wayzgoose. The weather is supposed to be perfect, so come on over and say hi to scads of letterpress artists, print your very own keepsake in the studios, and referee the Steamroller Smackdown outside. Jessica and I won’t be steamrolling this time, but we will have a table in the marketplace—so don’t be a stranger!

Here’s the skinny:

9th Annual Seattle Wayzgoose

Saturday, August 28, 2010

1 to 6 pm

Free!

School of Visual Concepts

500 Aurora Avenue North, Seattle

More information and RSVP here

The lovely ‘Goose wranglers at SVC asked me to design this year’s postcard; I think I was watching too many Japanese monster movies at the time. But monsters and letterpress seem to go well together; the postcard is lovingly letterpress printed by the talented titans at Evolution Press

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)