Blog

October 27th, 2009

Now that we live in a vacation destination, we tend to get a lot of out-of-town visitors. We have a list of favorite places to take first-timers, so we can often be found at places like the Pike Place Market, Point Defiance, and Mt. Rainier with house guests in tow. When a pair of French foodies arrive on your doorstep, however, it’s a whole ‘nother ballgame. Our friends Gilles and Jean-Philippe had just one major request for their visit last weekend: mushroom hunting. Since it’s chanterelle season and the weather was good, Saturday seemed like a good day to lace up our hiking boots and grab our pocket knives.

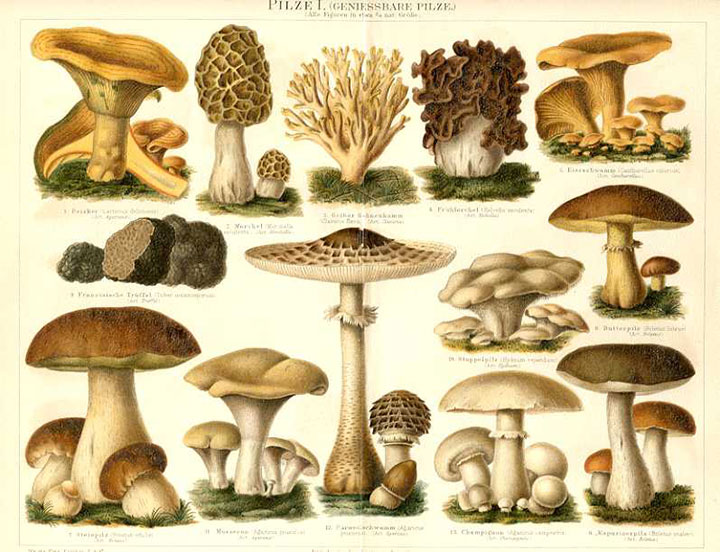

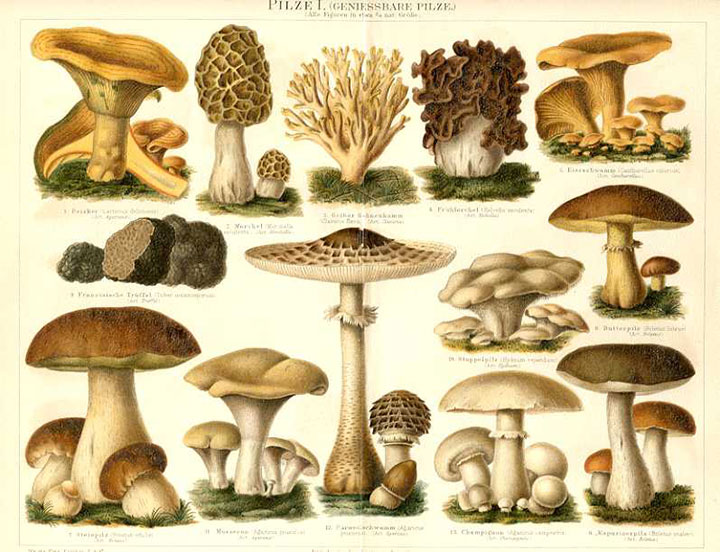

Disclaimer! The Tailor and I are not experienced mushroom gatherers, so we’d never try this on our own—incorrectly identifying edible fungi is not a mistake one wants to make. Even the most detailed books can’t replace the presence of a skilled guide, so if you don’t have your own French mycophile on hand to take you hunting, skip the risk and buy a bag of chanterelles at the farmers market!

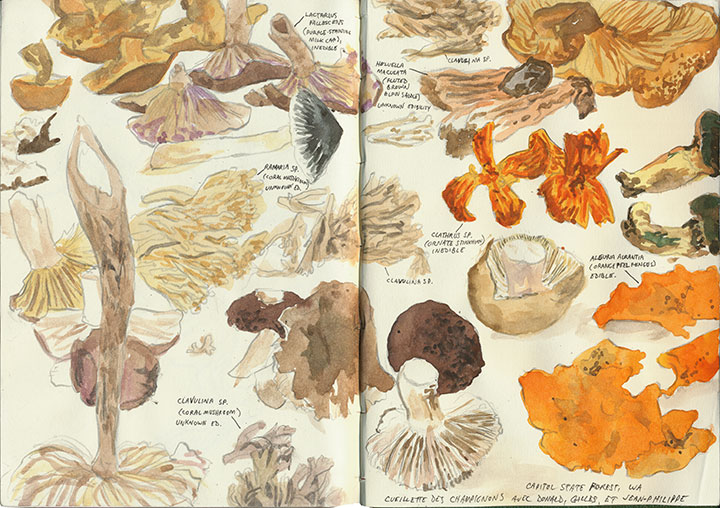

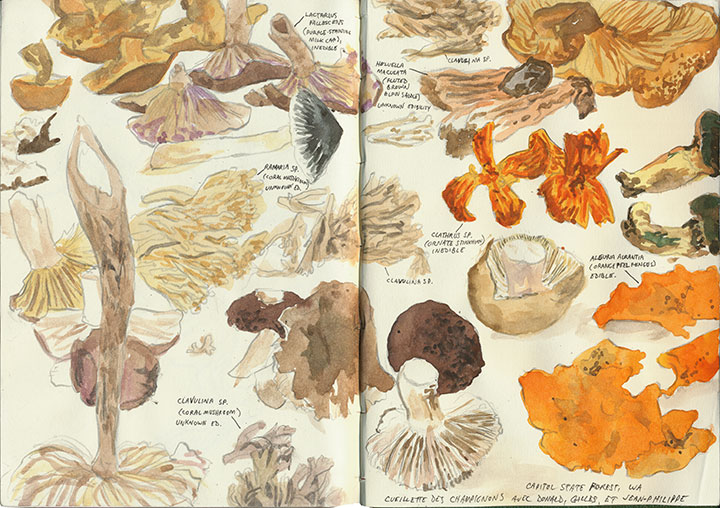

As far as dinner ingredients go, we came away empty-handed—the conditions just weren’t right. But as a crash course in the sheer diversity of local fungi, it was a spectacular day; we found several dozen different varieties ranging from beautiful to bizarre; delicate to disgusting.

We did find a few edible species (these orange peel cups were a beautiful and exciting highlight), but nothing worth turning into a meal. So the day turned out to be more of a scientific field trip—certainly a worthwhile adventure in its own right.

When we got home, Gilles spread out our haul and set to work identifying, making us laugh whenever he called out something strange (stinkhorn, elfin saddle, hedgehog—called sheep’s foot or pied-de-mouton in France).

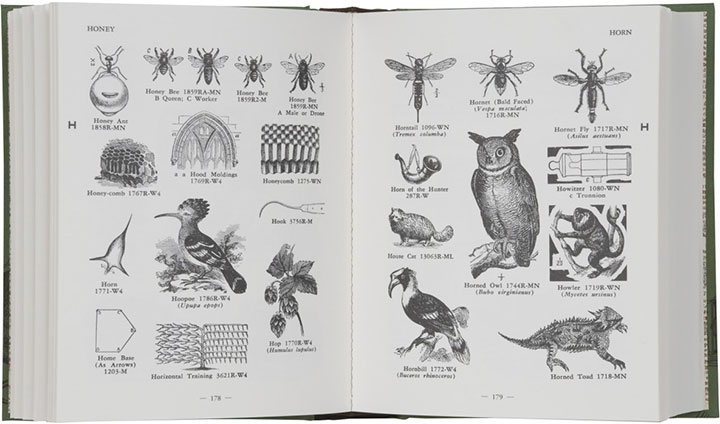

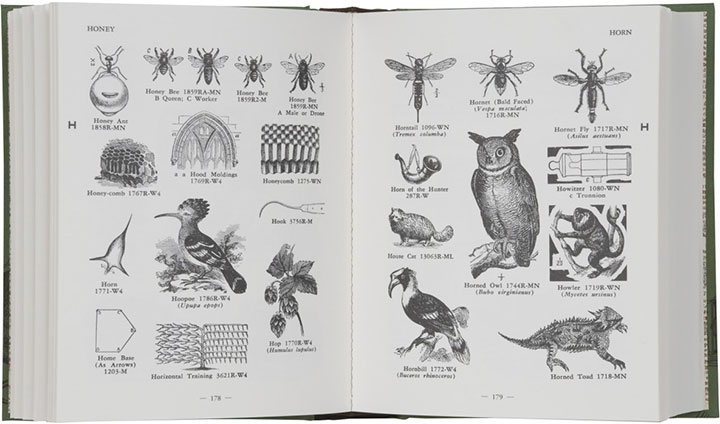

As for me, all this mushroom-naming reminded me of the newest addition to my reference library: the stunning Pictorial Webster’s, by book artist John Carrera (for a mind-blowing art experience, check out the video on the process behind the book here). So I took a page out of his book (sorry, I couldn’t resist), and did a little visual taxonomy of my own.

Jean-Philippe, meanwhile, had the best idea yet: purchasing a pound or two of fresh chanterelles, and putting his mad French cooking skills to work. The sumptuous champignons dish he whipped up disappeared into our mouths long before I thought to grab the camera, but I did remember to ask for the recipe:

Chanterelles à l’improvisation

– 1 1/2 pounds fresh chanterelle mushrooms, halved

– 1/2 cup bacon (3 slices or so)

– 1 medium yellow onion, chopped

– 4 to 5 Tbsp olive oil

– 1/4 cup dry white wine (the Muscadet we had on hand was great)

– dry parsley to taste (fresh is better, but we didn’t have any)

– salt and pepper to taste

Brown the bacon until crisp, then break into small pieces. In a separate, large pan (so as not to overpower the mushrooms with the flavor of bacon fat), sautée the onions in olive oil over medium-low heat until lightly browned. Add the chanterelles, bacon, salt, pepper, and white wine, and sautée until the mushrooms are slightly limp and drained of most of their water content (oh, say 5 or 6 minutes). Season with parsley at the very end, then serve either alone or over brown rice. Watch the dinner conversation devolve into a series of satisfied grunts.

October 17th, 2009

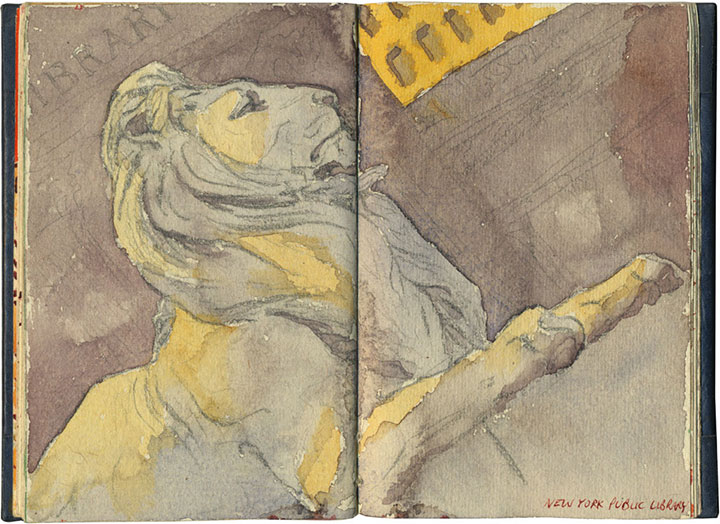

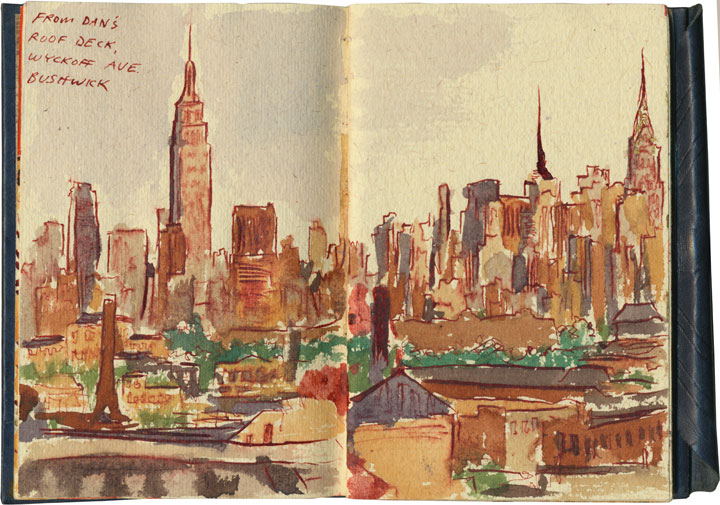

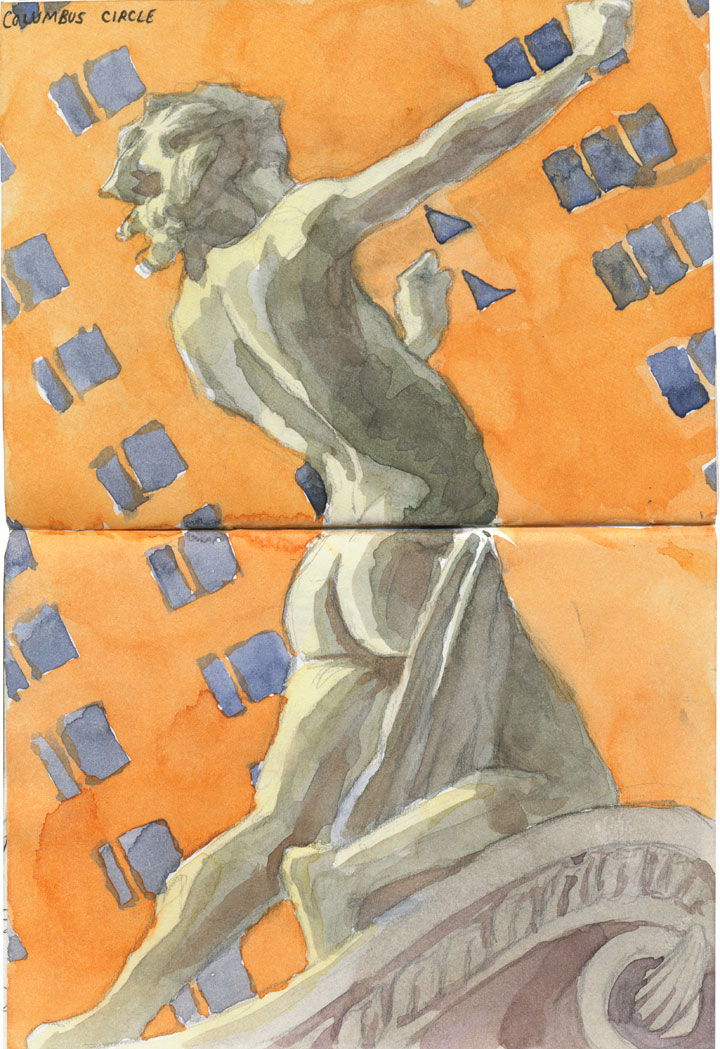

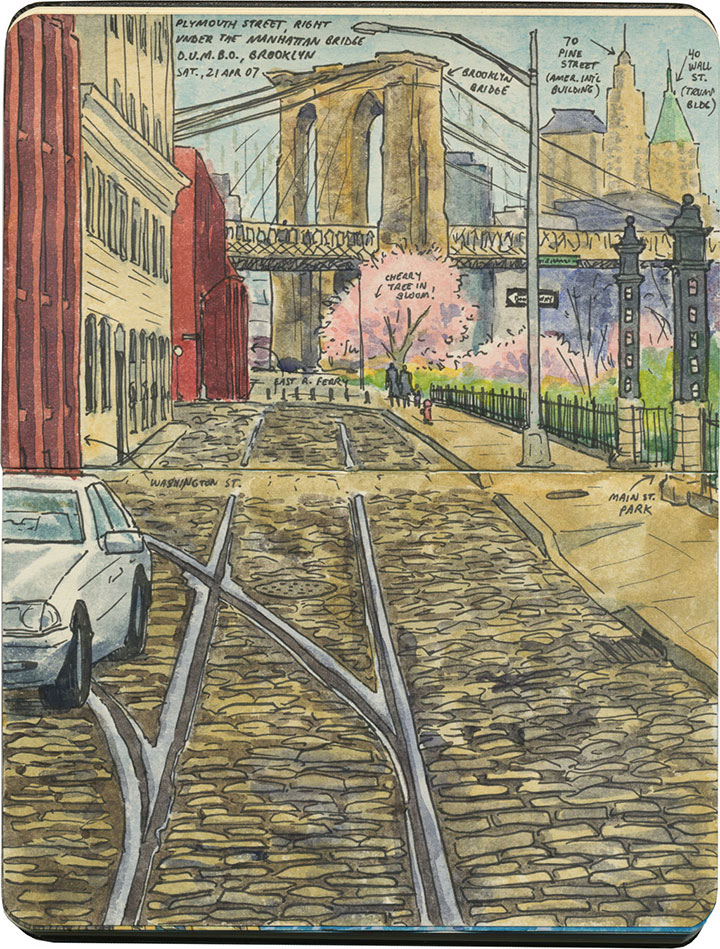

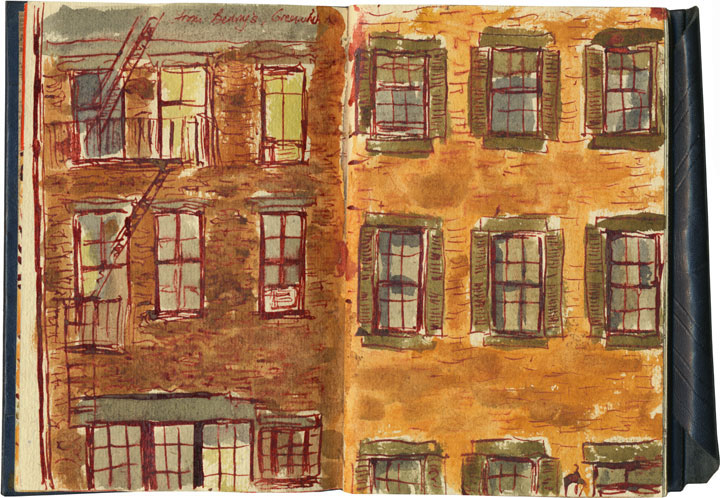

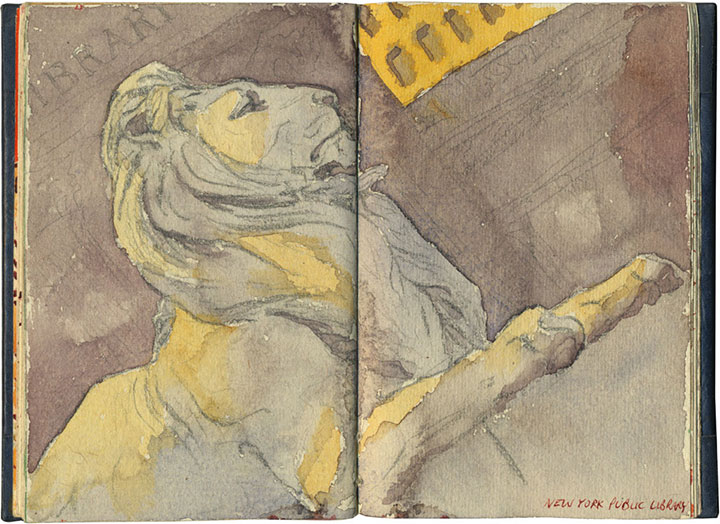

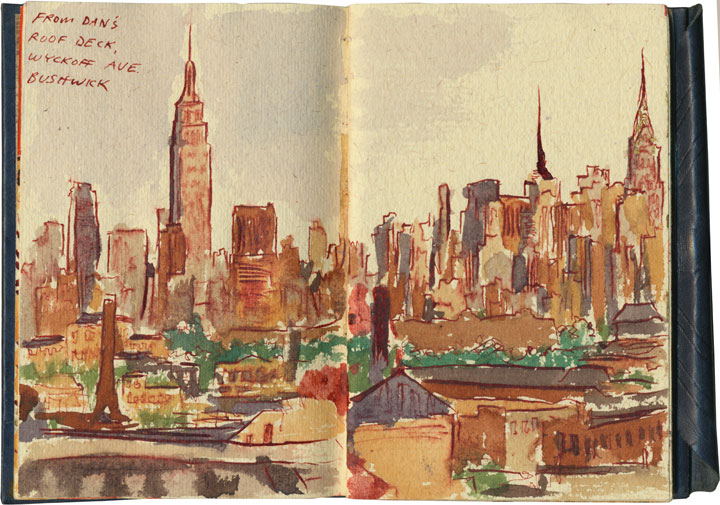

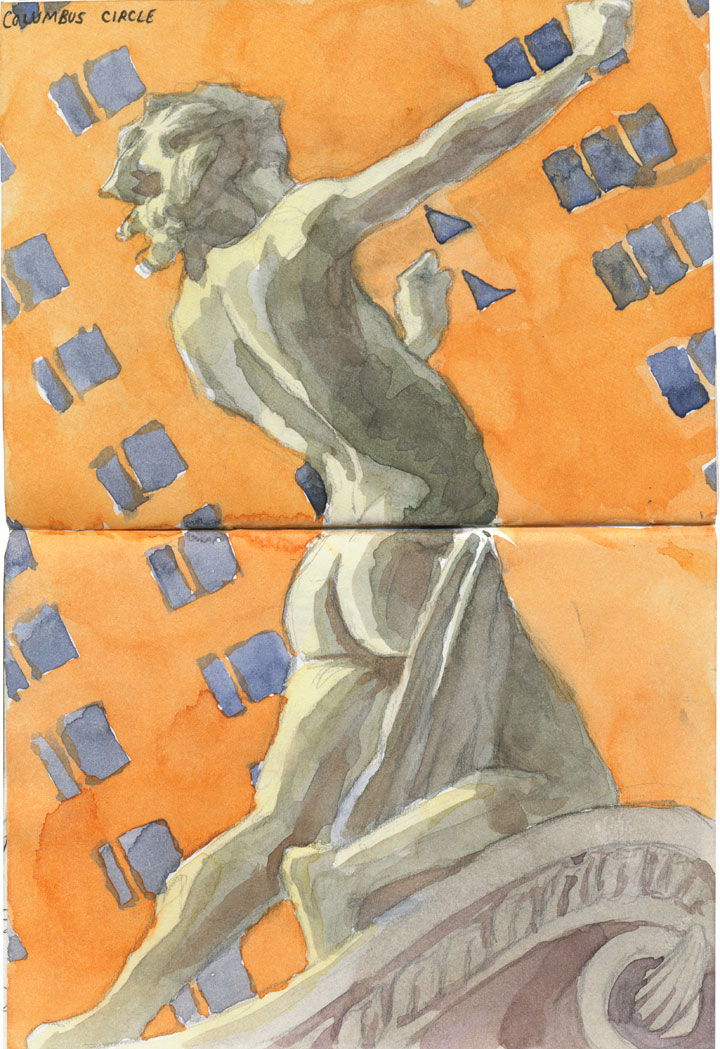

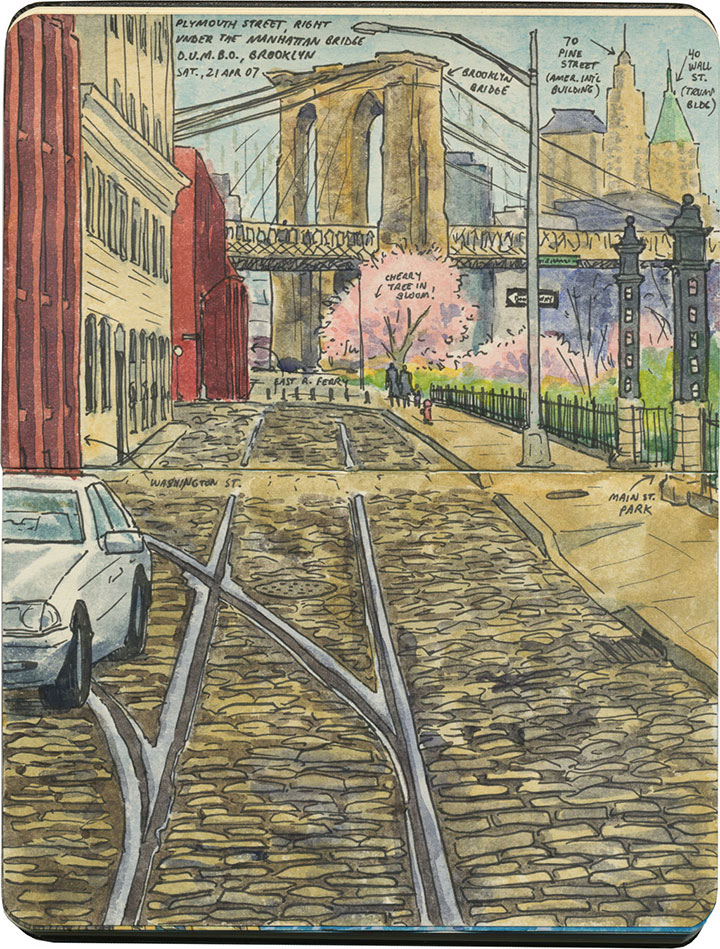

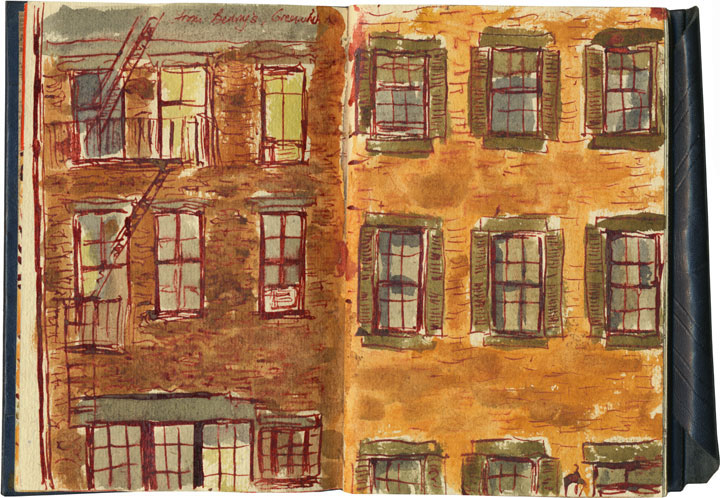

Last week I spent a few days in New York for the wedding of some dear friends.

I lost track long ago of just how many trips I’ve made there over the years, or how many months’ residence would equal the sum of all my days spent there (plenty).

My memories and souvenirs reflect this. I have whole sketchbooks devoted solely to Manhattan; boxes of still-good Metrocards and train schedules; miles of film negatives and a mental Rolodex stored to the brim with makeshift maps, habitual errand circuits and addresses of favorite haunts.

Every time I visit, it’s hard to string together a cohesive narrative of the adventure afterward.

Instead, my memories of New York are always a series of brief impressions; moments caught like fireflies in a jar.

Maybe it’s because each day finds me all over the map of the city, alternately in teeming crowds and completely alone;

or because I’d rather remember the best events and forget the worst (I’ve got a whole long list of those, too);

or maybe I owe it to the very nature of drawing and photography—whatever the reason, this trip was no different.

And every moment is another thread woven into a huge, neverending tapestry that tells the story of my very own, personal New York.

And for me, that’s the best thing about it.

September 8th, 2009

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m currently in the process of researching Mt. Rainier for my next artist book. This involves drawing and photographing the Mountain over and over (and over and over) again, in as many different conditions and from as many different vantage points as possible. I’ll get into the whys and hows some other time, but for now, suffice to say this is a huge challenge. Not only do we have incredibly unpredictable weather here, but Rainier also tends to play by his own rules, appearing and disappearing regardless of any logical connection to the forecast (which, somewhat ironically, is the entire point of my book…).

I’ve done my best to even the odds by doing the bulk of my research during the summer and early fall—traditionally the dry season here. This summer, however, has proven to be about as nontraditional as possible, and has thrown a whole lot of monkey wrenches into the works. For weeks I had planned a long trip to various points east, where the landscape is drastically different than here in the west. But here’s the rub: not only did I require a flawlessly sunny day to view the Mountain from so far away, but the best time to view Rainier from the east is in the morning—I’d have to leave too early to see that day’s weather report. So I waited, and stalked the National Weather Service, and packed and unpacked my gear. During our ridiculous heatwave we had day after day of beautiful sun, but hot weather makes the atmosphere so hazy that even from here, just forty miles away, Rainier was just a faint silhouette. And then it was one excuse after another; either I had an appointment or deadline I couldn’t change, or it was raining, or it was hot and hazy east of the Cascades, or there was a forest fire blocking my path (no joke!). Over a month went by like this, and I could feel my window of opportunity shrinking—many of the roads included in my plans are closed from October through June.

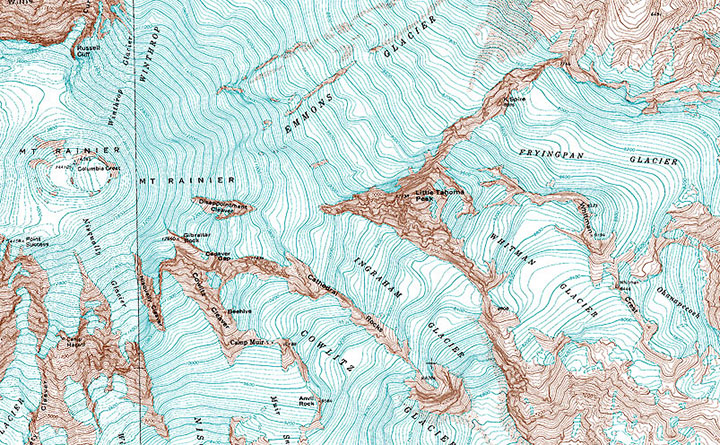

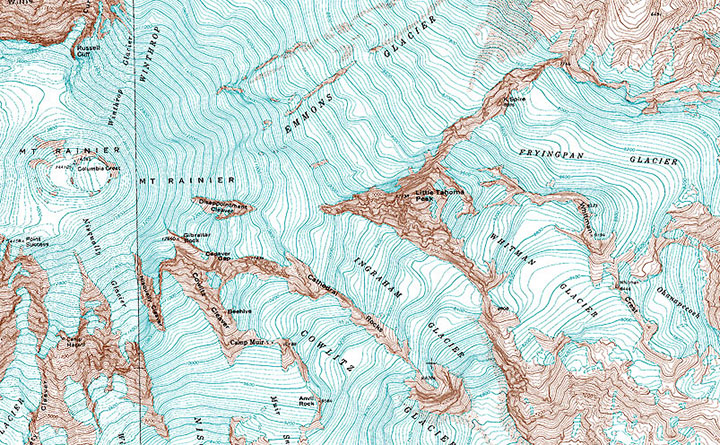

And then, a couple of weeks ago now, it seemed I’d finally get my chance. Every weather report promised dry, cool, sunny weather, for one lovely day, before the gloom closed in again. I packed my drawing paraphernalia, both cold and hot weather gear, a picnic lunch, a pile of atlases and topographic maps (you didn’t think I’d be using GPS, did you? When a letterpress printer marries a geologist, topo maps become a permanent fixture of both studio and science lab!), my camera, and plenty of music in the car, set the alarm for 3:15 am, and went to bed early with my fingers crossed.

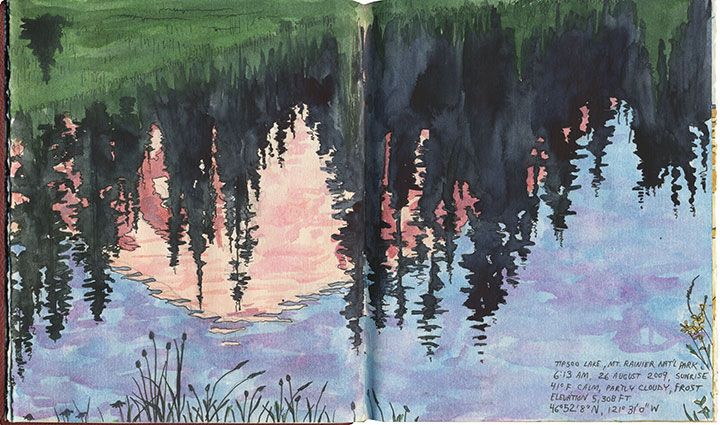

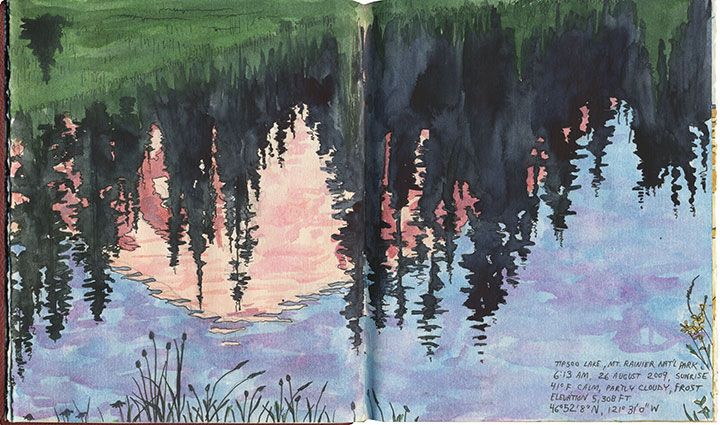

By 3:30 I was ready to go. I poked my head outdoors, saw stars overhead, and decided to make a break for it. Two hours later I arrived at my first stop: Tipsoo Lake, just off the road in an alpine meadow. To my immense surprise I wasn’t alone, even at that absurd pre-dawn, Wednesday hour, with the entire meadow blanketed with frost. A pair of photographers arrived just minutes after me and set up tripods nearby, and a friendly Slovak couple emerged from their tent to introduce themselves while we waited for the sun to rise. The biting cold made me question the sanity of this trip, but when the light finally spilled over the ridge to dye the Mountain pink, all my doubts disappeared.

I stayed just long enough to block in a composition and shoot a few reference photos before the light changed and I lost the moment (I was on a tight timetable all day, so I finished all of these sketches back in the studio). I checked my watch and hit the road again (and waved to the Slovaks as I passed them again, thirty miles later).

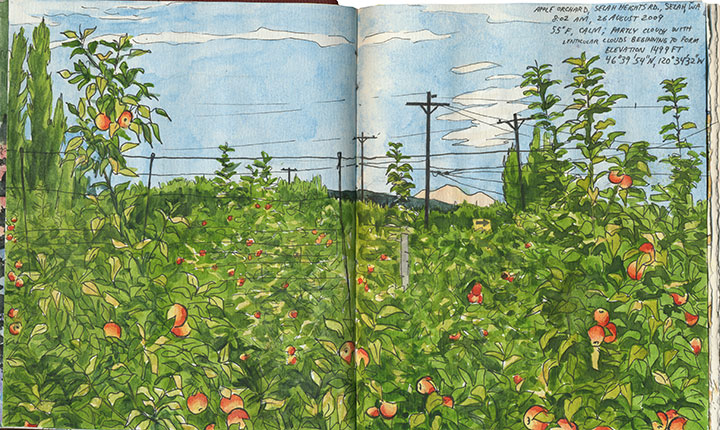

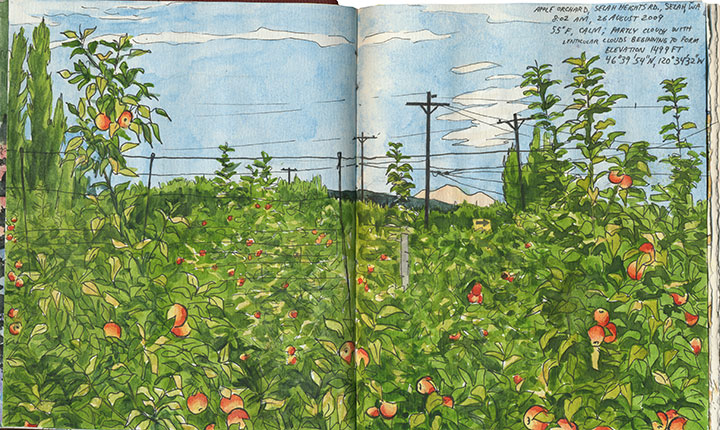

From here onward I had to work entirely on conjecture. Tipsoo Lake is a famous, oft-photographed spot, so I knew what sort of composition I wanted. But I had no photo reference for the rest of my guesses that day, only an idea of what I was looking for and a lot of half-memorized topographic maps. I was hoping to capture a scene of Rainier through the iconic apple orchards of Yakima, but I knew (from all the neck-craning I’ve done on previous drives through the region) that for the most part Rainier isn’t visible from the Yakima Valley, where most of the fruit trees are. According to my maps, though, there were some flat, gridded regions at the top of the bluffs overlooking Yakima—I hoped the grid meant farms, and that the extra 600 feet in elevation would be enough for a glimpse of the Mountain. So I made for Selah Heights Road—a hairline even on my most detailed map.

The road climbed past rows of poplars, trees laden with fruit and sweeping views of the valley; so far, so good.

And then I found it: just the tip of Mt. Rainier visible between the apple trees. I couldn’t believe my luck. And just as I finished roughing out my drawing (I still had a lot of miles to cover before my next destination, so I worked fast and loose), I glanced to my left and discovered another treat:

Mt. Adams, for a little extra credit.

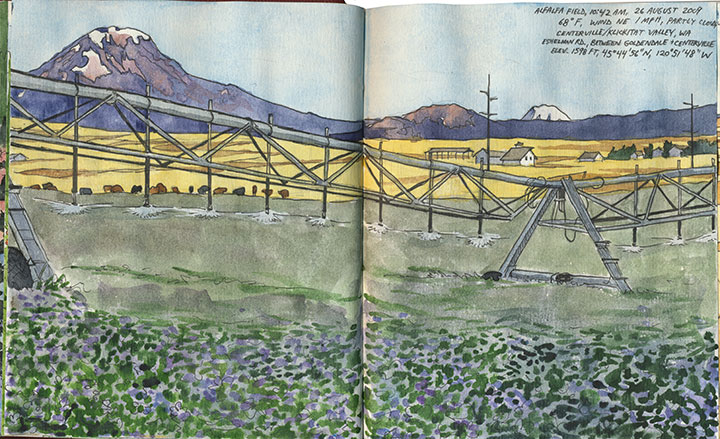

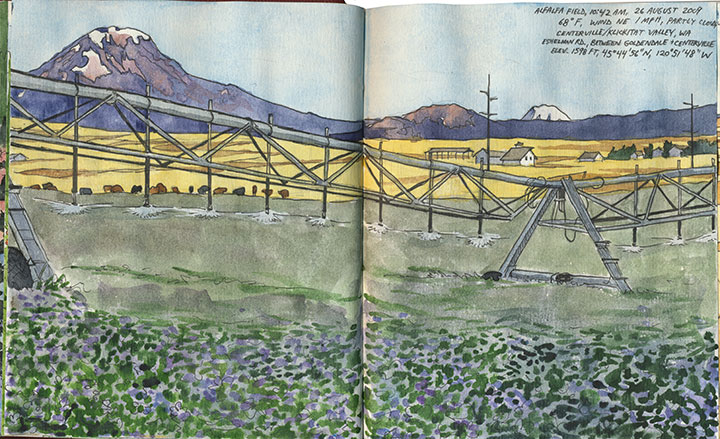

After a quick, desperate and delicious coffee in Yakima, I turned south. My next stop was a place I’d never been: the Centerville Valley, a high-plains agricultural area just beyond Goldendale.

I knew that Adams would be prominently visible from here, but I could only hope that Rainier was as well—it sure would make a pretty picture if it were, I thought.

Nope, still Adams—although from this angle it tends to fool people (and cows).

I looked behind me, and saw that the farmland sloped upward a bit, before giving way to the Columbia Hills. So I headed south along a dirt road for about a half mile, parked, and trudged a few yards into a field of wheat stubble.

Bingo.

The alfalfa blossoms were sheer luck, just like so many other things that day. And that irrigation rig was moving—so I was never more thankful for digital photo technology than that moment (as a die-hard darkroom enthusiast, I never though I’d say that!).

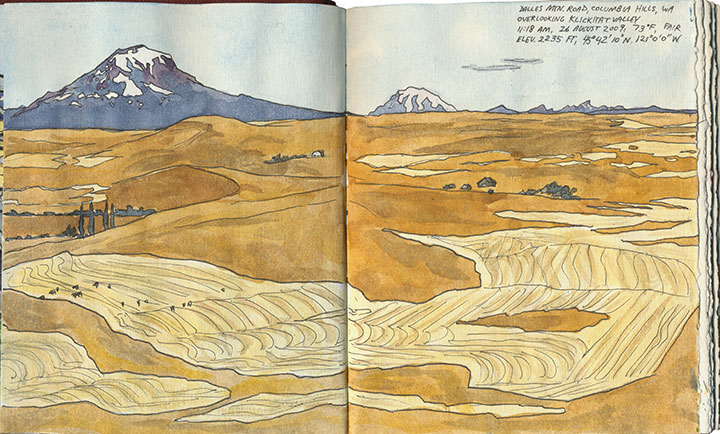

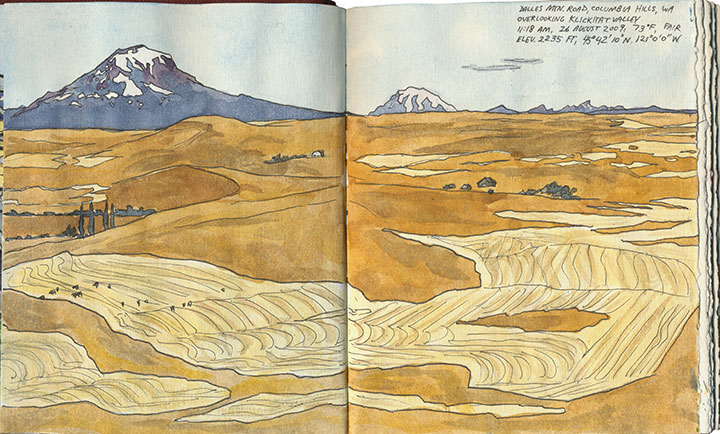

Only one item remained on the itinerary: a narrow, winding goat track called the Dalles Mountain Road.

The spectacular vista of Adams, Rainier and the valley was just the beginning.

The road snakes over the top of the Columbia Hills, providing views of five volcanoes (that’s Hood there)…

pockets of stunning wildflowers…

and plenty of road-side snacks.

On the southern slope of the Hills the landscape turns suddenly rocky,

and the mighty Columbia River bursts into view.

My research had gone off without a hitch, and right on schedule. It was only just noon: mission accomplished. So to celebrate I stopped for lunch at one of the most stunning picnic spots I’ve ever seen.

From that little patch of grass I could have chosen to go home the way I came, or finish the loop and return along the western side of the Cascades—it was almost perfectly equidistant. So as usual I chose the unknown road, and zipped home via the historic Columbia River Highway.

Fifteen hours, 515 miles roundtrip. And perfect conditions every step of the way. I think that after a summer of total frustration (remember the airplane incident?), maybe the universe decided to give me a break.

I’ll be sure to send a thank-you note.

July 6th, 2009

In my (so far) limited experience, Washingtonians tend to be outdoor types—and with good reason. With so much beauty at our fingertips, it’s no wonder that with the first hint of a sunny day, we’re out in force. Add to that the near-clockwork arrival of the dry season by Independence Day, and the fact that huge swaths of the mountains are inaccessible for nine months out of the year—well, you can see where I’m going with this. Since the Fourth of July was kind enough to fall on a Saturday this year, the cities emptied and thousands headed Outward. And this year, though we’re normally Off-Season, Off-the-Beaten-Path types, the Tailor and I were no exception. Like zombies we staggered outdoors to pack our tiny Subaru sedan—must … go … camping!

We knew it was probably folly, but we had a goal in mind: find a beautiful, mountainous campsite away from the teeming hordes. We knew Mount Rainier would be out of the question, as were the Olympic Peninsula, Mount St. Helens, or any other popular tourist destinations—but even though we had a head start by leaving on Thursday afternoon, our hope faded as we saw the crush of fellow vacationers on the freeway. “Camper … camper … RV … canoe … RV … kayaks … cyclists … camper,” the Tailor droned, counting cars, “this was a dumb idea.” Yet as our route took us on smaller and smaller roads, the number of fellow travelers dwindled almost to none. It began to seem like our instincts were right after all.

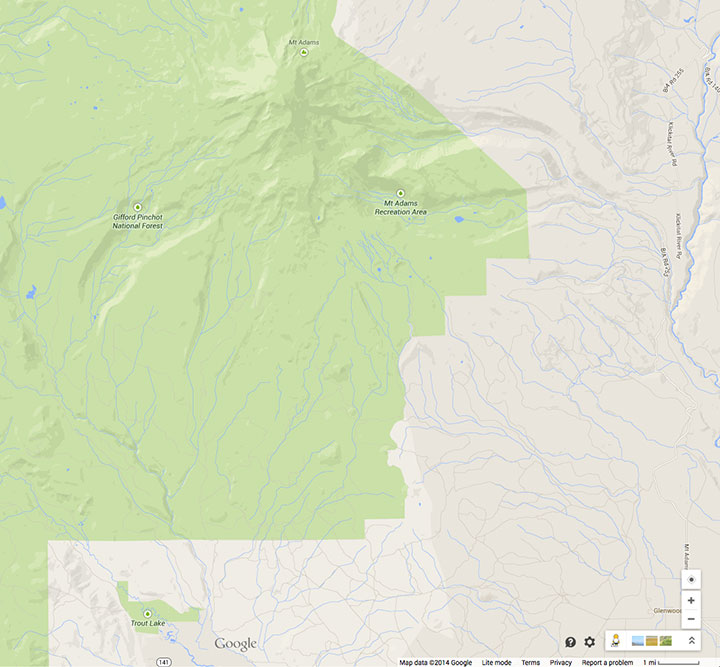

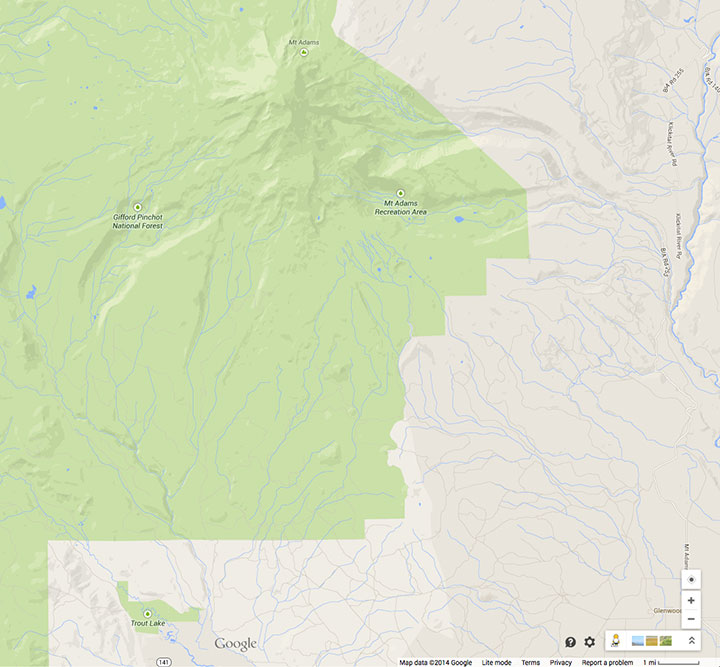

Our destination? The Morrison Creek Campground, located on the southern slope of Mount Adams, Rainier’s slightly-smaller, lesser-known brother.

While we were nervous of the possibility of any volcano attracting busloads of holiday tourists, our choice had a couple of points in our favor. For one thing, one can’t reserve a campsite in a national forest; all sites are taken on a first-come, first-served basis. For another, Morrison Creek is in the middle of freakin’ nowhere.

The only way to get there from the north is to use the system of Forest Service roads that wind through the Gifford-Pinchot National Forest. The paved sections are breathtakingly beautiful and super fun to drive (especially with a stick shift; I felt like I was filming a car commercial). The “unimproved” stretches, on the other hand, range from challenging to terrifying. Mindful of the consequences of puncturing an oil pan or snapping an axle on a holiday weekend in one of the most remote pockets of the state, I took my sweet time picking my way around the detritus of recent rock slides and dodging monstrous potholes.

When we pitched our tent just as the last light faded, however, we knew that it was absolutely worth the trip. Our campsite was in a lovely, secluded spot, adjacent to the Creek, just below the last traces of mountain snow, and surrounded by pockets of blooming beargrass. And to our immense surprise, we had Adams almost entirely to ourselves, for the whole weekend—funny, considering that the next campground, three miles up the road, was crawling with mountain climbers.

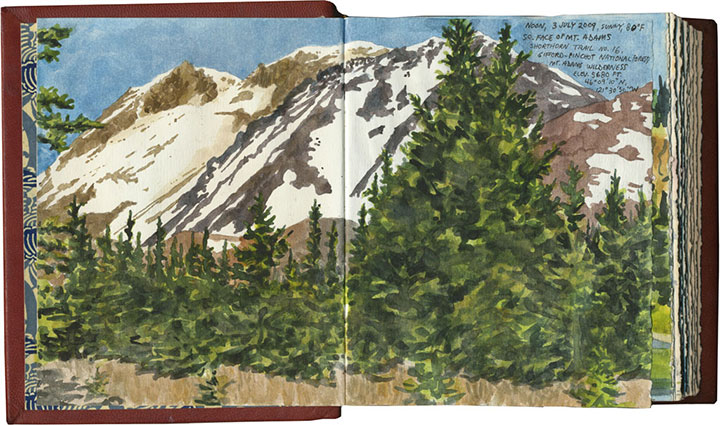

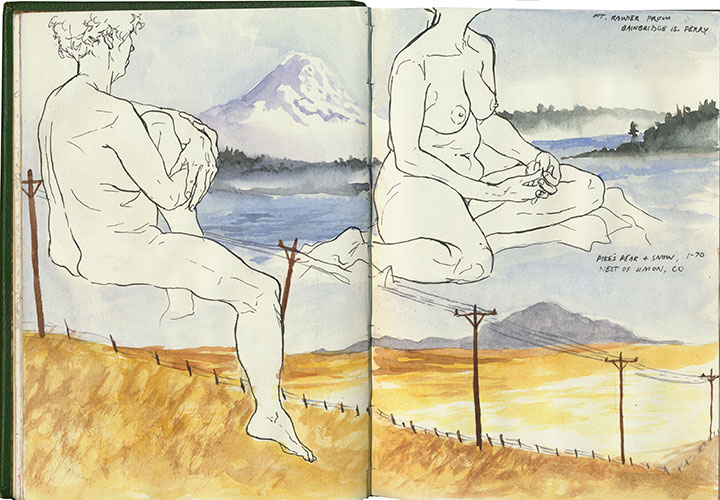

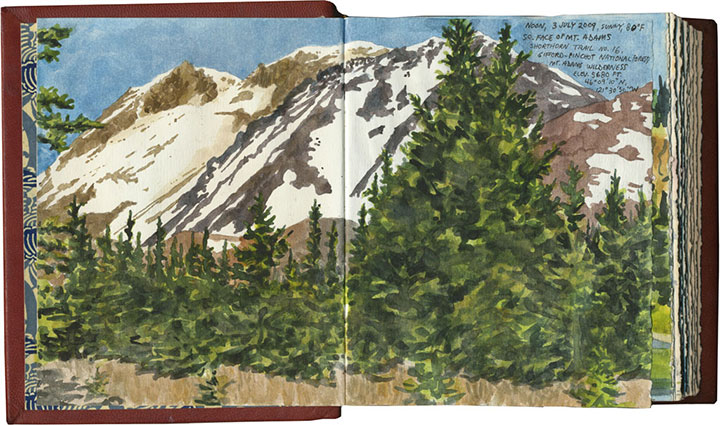

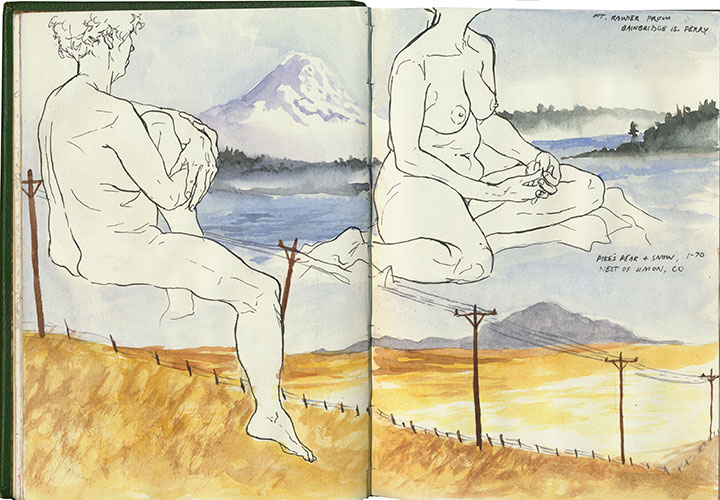

I was hoping our travels would afford us at least one view of Rainier in the distance—that way I’d have another sketch to add to my store of potential artist book imagery. FS Route 23, however, doesn’t afford such a vista, and any potential viewpoint reached by hiking trail was well out of range of our abilities. A two-mile hike from our tent did give us a spectacular, alpine-meadow view of Adams, though—and I realized that for my research purposes, I could use the peak as a sort of stunt double.

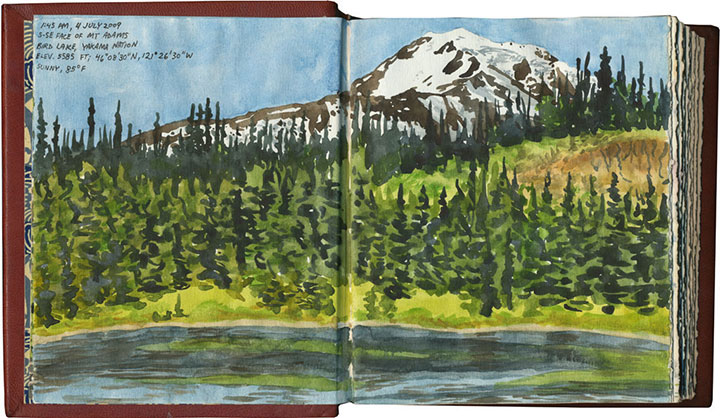

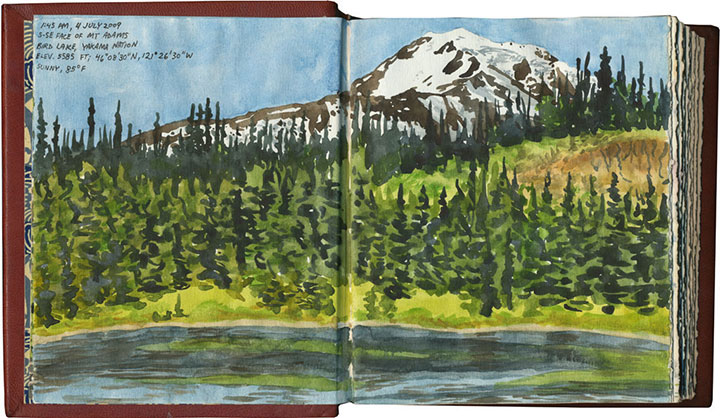

From certain angles, Adams is remarkably similar to Rainier (and people often mistake one for the another when viewed from a distance). All the more reason to use my time there for drawing. I was surprised to see, however, how drastically Adams’ appearance changed, depending on the vantage point. This is the view from Bird Lake, on Yakama Nation land, just a couple of miles (as the crow flies) east of Morrison Creek:

And though there was nowhere to sit to capture it in my sketchbook, a gap in the trees gave me the chance to glimpse another stand-in to the south: Mount Hood.

What an incredible weekend. As you can probably guess, Adams is on the short list for Best Camping Spots Ever, and I’m sure we’ll end up returning again and again. Next time, though, it might behoove us to reconsider our mode of transportation; it’s doable in a compact car (just barely), but I think I’d rather rent a pickup truck—or a mountain goat.

June 30th, 2009

A few months ago I was granted funding by the City of Tacoma Arts Commission to create my next artist book edition. Since this is the first of what will probably be a long string of posts over the next eighteen months, I’ll save the details for later. For now, I’ll just say that the book deals with the changing appearance (and intrinsic nature, since it’s an active volcano) of Mt. Rainier. At the moment I’m knee-deep in research, trying to capture the Mountain in as many different—well, attitudes, as Jane Austen would put it—as possible.

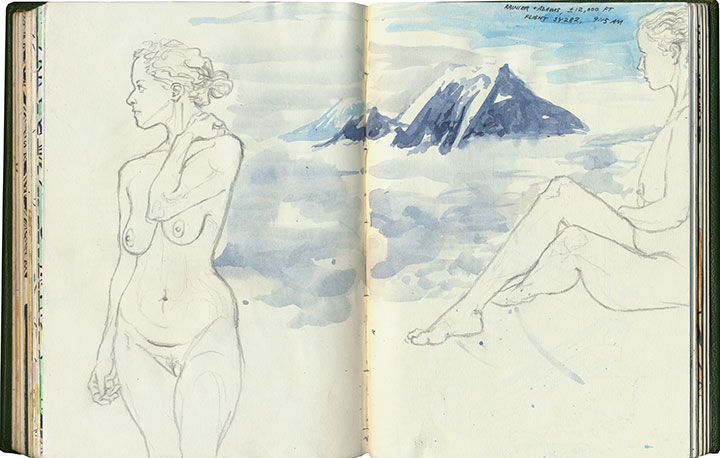

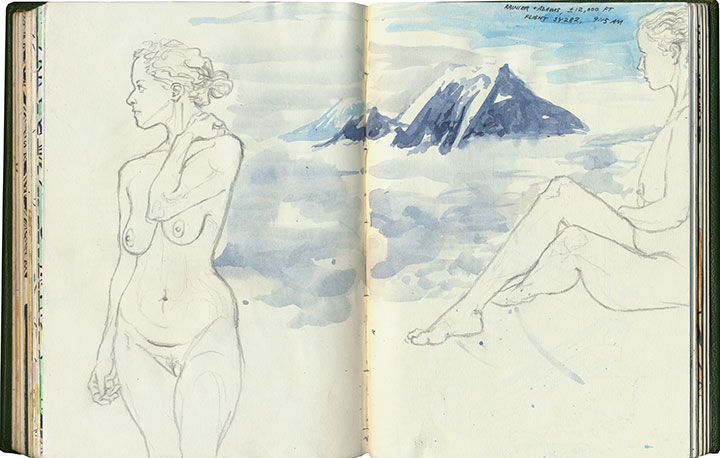

The Tailor and I spent last week visiting old friends and haunts in Minneapolis, and as luck would have it, I had the window seat on the south side of the plane on our flight out. I had my paints, brush, and film canister full of water ready as we taxied, so that when we cleared the cloud ceiling I had a solid two minutes or so for a sketchbook snapshot.

It occurred to me, though, that while a 120-second gesture painting (complete with frantic paint spatter) would be a nice addition to the sketchbook, it wouldn’t provide nearly enough reliable detail to serve as the basis for a future letterpress print. So on the way back, I requested another window seat (I think the fact that I’d sprained my ankle on our last day of the trip, and had to hobble to the counter, might have helped my case a bit) so as to document any Mountain sightings with the camera.

The counter attendant had been kind enough to place me on the correct side of the plane again. And the weather was crystal-clear, affording the passengers with stunning, morning-lit views of Rainier and the entire Cascade volcano chain. The cabin was filled with sounds of hushed awe and clicking shutters. There was only one snag in my research scheme—Row Nine, in which we were seated, seemed to use the term “window seat” loosely.

And the universe kept right on laughing.

May 30th, 2009

Oh, I’m probably asking for it with this post title. (To anyone who might have found this post by Googling naughty things, I’m afraid you’re about to be disappointed.)

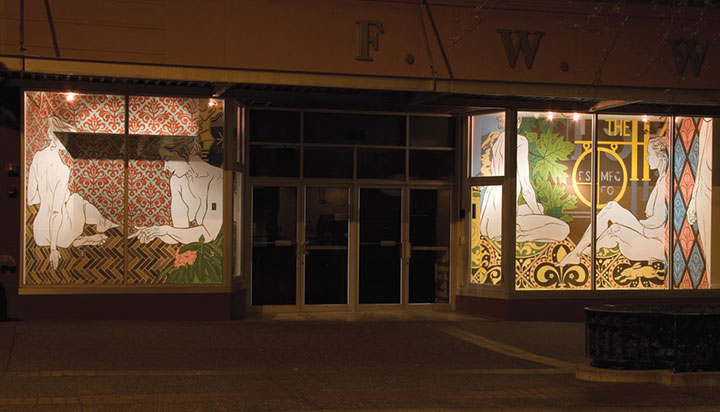

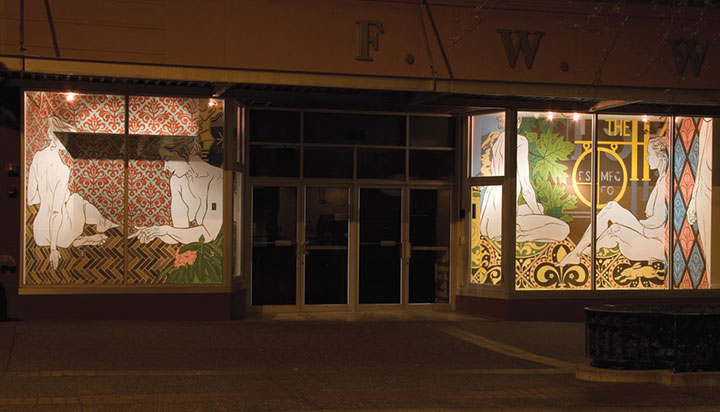

The window displays in the old Woolworth’s store downtown have been converted into a twenty-four-hour gallery, with artist exhibitions and installations rotating quarterly. Shortly after I moved to Tacoma, I found out that they were accepting applications for the 2009 gallery slots. I thought it might be a good opportunity to try out a crazy idea I’d been playing around with, so I decided to give it a go.

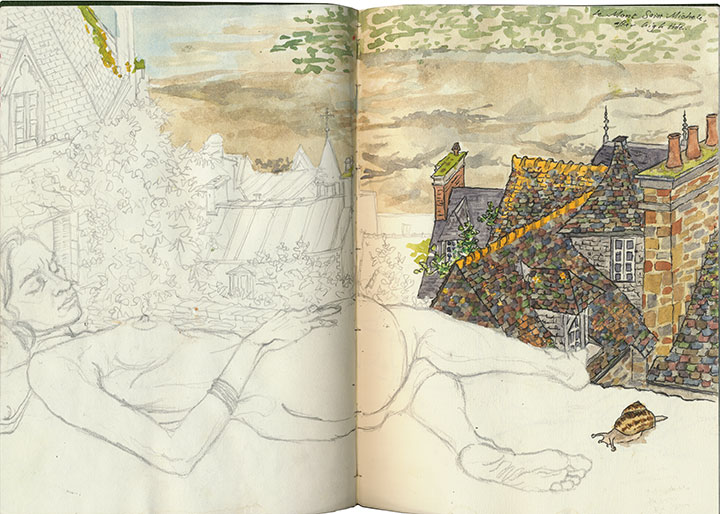

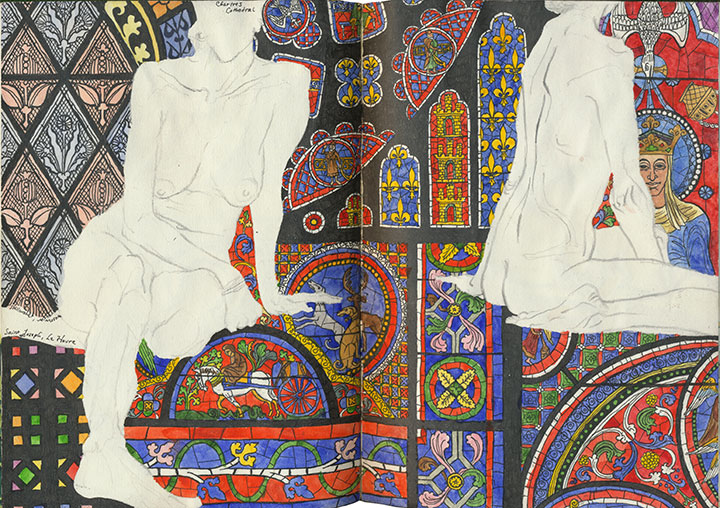

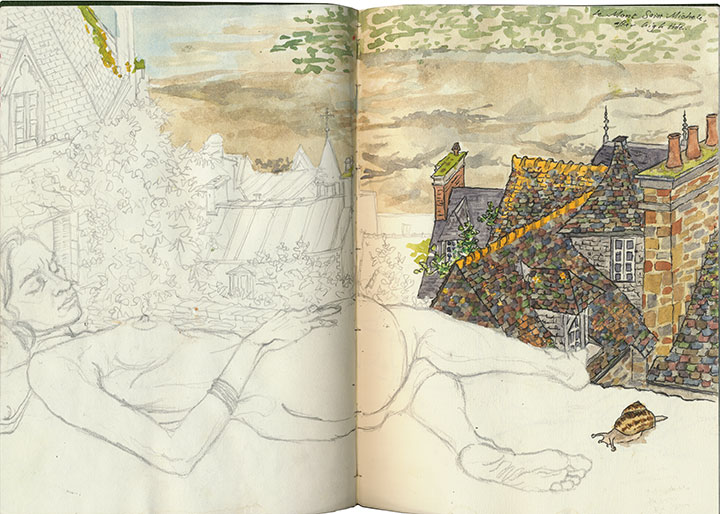

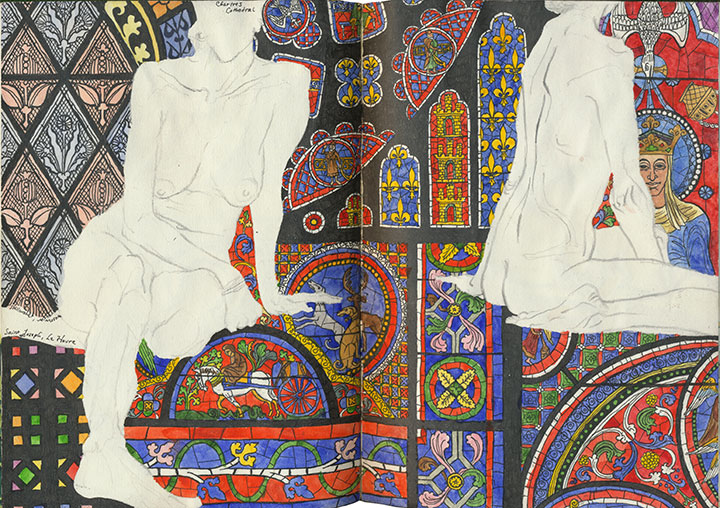

For many years I’ve carried a sketchbook everywhere I go, but for the last couple I’ve been experimenting with something a little different. One day I was in a hurry, and knew I wouldn’t have time to fill an entire spread with the watercolor sketch I wanted to make. So I chose a page that already had some figure drawings on it, and just painted within the negative space around the figures.

And from then on I couldn’t stop. Once the number of watercolor paintings began to catch up with my stock of line drawings, I started attending model sessions again. This time, though, I used the figure drawings to compose the page, with the expectation that eventually I’d go back in with another sketch later.

Several people told me they’d like to see these drawings on canvas or framed on a wall—and more than one suggested a wall mural version. Besides, the conceptual link between nude figure drawings and mannequins in a store windows was too tempting to resist. So I applied for a Woolworth Windows show, but I guess I never expected that my proposal would be accepted. I was talking about gigantic nudes on a busy street, after all. When the notification date came and went without a word, I assumed the project had been rejected and moved on. And then, three months later, I received an email that said, “Congratulations! By the way, your show begins next weekend.”

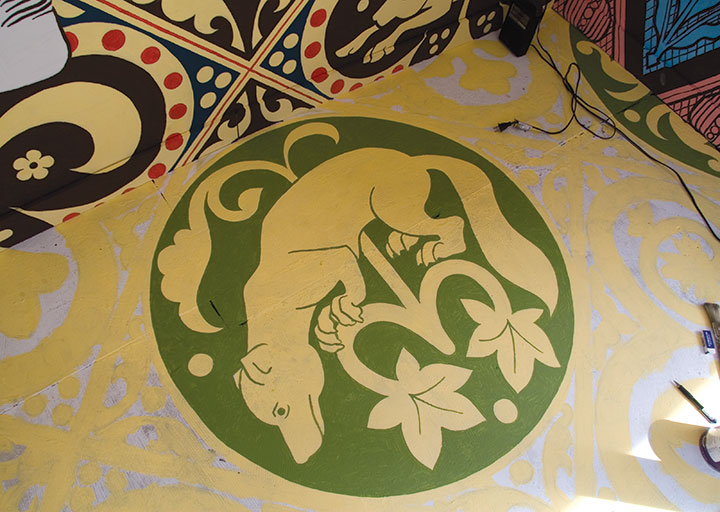

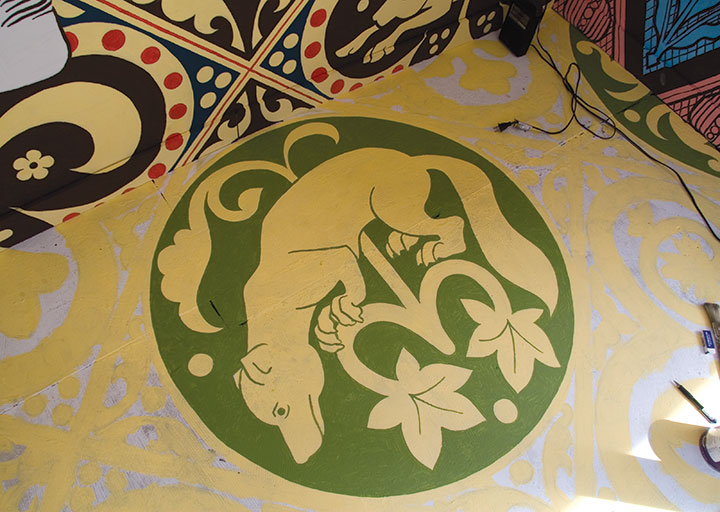

Now, I’m not normally an installation artist, but I do have six years of technical theatre and several large-scale murals under my belt. Still, there was something rather daunting about being thrown in the deep end of a double installation project, which involved attempting to paint proportionally accurate, ten-foot-tall nudes inside a narrow, very public glass box. A very monkey-cage-at-the-zoo glass box. To be fair, every mural I’ve ever painted has begun with a ripple of fear, and thoughts ranging from “Oh, right, I forgot how big walls are,” to “For the love of Pete, how did I ever convince these people that I was capable of painting something that actual humans would be able to see?” Depending on the scale of the project, of course—hey, if blank pages can be intimidating, blank walls (and tall ladders) are pretty terrifying. So this time, what with the many passers-by glancing in at me, I needed a few extra deep breaths. It’s funny that I still get that little moment of panic—because once I finally start in with either pencil or brush, I feel right at home, and even the ladder becomes an old friend. There’s just something so satisfying about slathering paint on a wall.

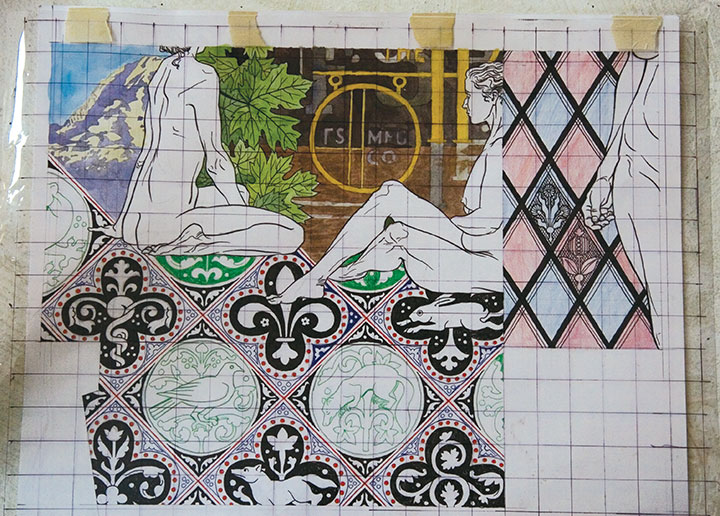

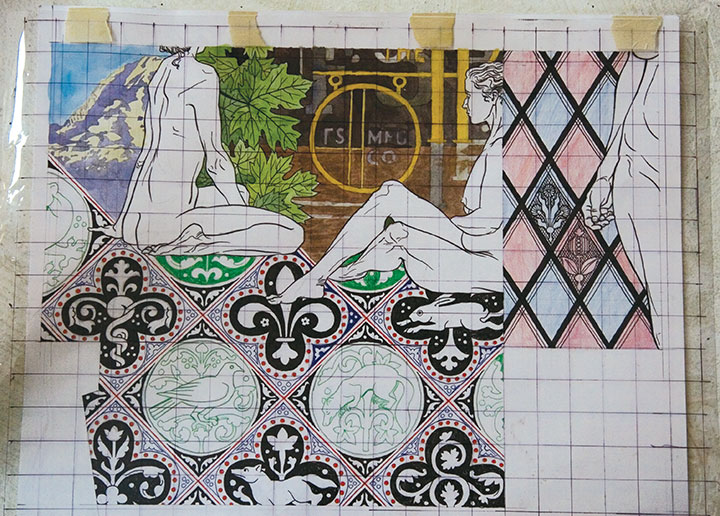

One of the challenges of the Woolworth Windows was getting my design up on the wall, at the correct size, without distorting anything. If I were painting a scenic flat for the theatre, I’d just photocopy my design onto a transparency, hook up a projector, and blow up the drawing to whatever size I needed. In a window display, however, there simply isn’t room to put a projecter far enough away from the wall. So I did it the old fashioned way: made my rendering to scale, laid a grid over it, and drew the same grid at the larger size on the wall.

You can see a little of the pencil grid in the top photo; in the left-hand window the pattern repeats did most of the work for me.

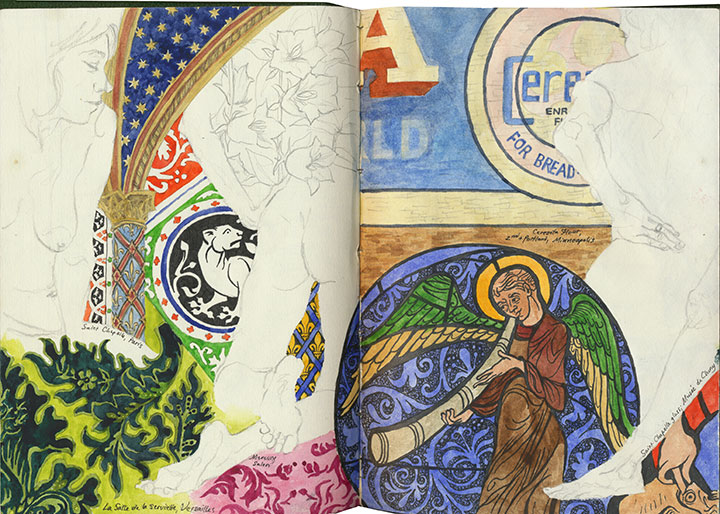

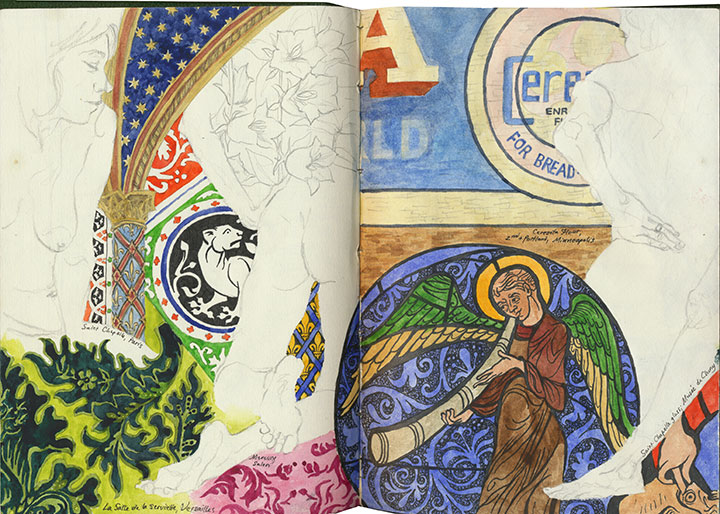

Like the drawings in my sketchbook, the inspiration came from a variety of sources. This pattern was an original design, but I was heavily influenced by the patterned brocades I saw at Versailles (see below).

Another element from this sketchbook page found their way into the design—my drawings of the inlaid floor of Saint Chapelle in Paris became the basis for the floor of the right-hand window.

The windows also contain elements found closer to home: bits of historic Tacoma signage,

and a stained-glass window in the home of my friend Christina, who lives in a former church.

Since I had a lot of equipment to stash in such a small space, I had to paint in a piecemeal fashion,

moving my supplies closer to the door as I painted myself into a corner.

Despite the challenges of the installation, this has been one of the most interesting and fun mural projects I’ve ever done. For one thing, I fulfilled a secret childhood wish to be “one of those people” who designed and created window displays (I was a big fan of Mannequin). For another, the best part about painting in public is that you get to meet all kinds of wonderful people. Everyone I’ve seen has been incredibly supportive, curious, and thoughtful. Mothers wheeled their strollers right up to the window so their toddlers could press up against the glass and watch. School kids on a field trip gathered around my rendering and recognized the Harmon sign immediately. Street-smart teenagers stopped to ask insightful and challenging questions about gender roles in art. Friends brought me coffee on a chilly day, or kept me company when I started to get tired. Business people flashed me a thumbs-up on their way to work, and neighborhood regulars shouted their encouragement through the glass. I guess I didn’t have to worry about the public reaction to a bunch of naked ladies after all.

There’s a catch to all of this, however: the installation is temporary. The last day of my show is June 13, and then I have to paint everything white once more. So stop by while you can—you’ll find these ladies on Broadway, close to the corner of South Eleventh Street (on the same block as the Thursday farmer’s market).

I guess that’s another thing all those years of theatre taught me: how to practice a little detachment when you have to dismantle what you built.

Even if it were only up for a day, though, it would have been worth it.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)