Living history

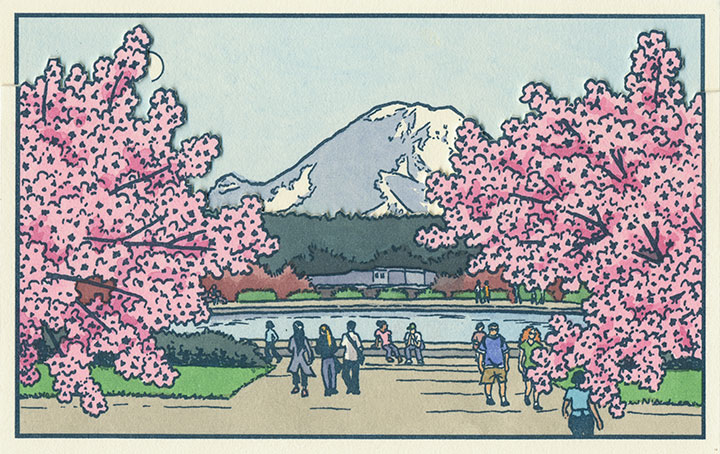

A composite of two image flats from the book.

Anyway, after a good, long run, my Local Conditions exhibit is closing tomorrow afternoon, and this week I’ve been revisiting some of my favorite images from the book. This one always gets me thinking about how much a city can change over the course of a century, and how for a newcomer like me, that change isn’t always apparent. There aren’t always little plaques or signposts to tell you what used to exist where you’re standing now—or even any evidence at all of how things used to be.

This scene depicts the Drumheller Fountain (also known as Frosh Pond), located on the University of Washington campus in Seattle. Incidentally, on my first trip to the Northwest almost exactly four years ago, I was standing on this very spot when I saw Mt. Rainier for the first time. This is where the idea for the book first struck me—although at the time it was a very different, and much simpler concept. And at that moment, I had no idea that the view itself had a history all its own.

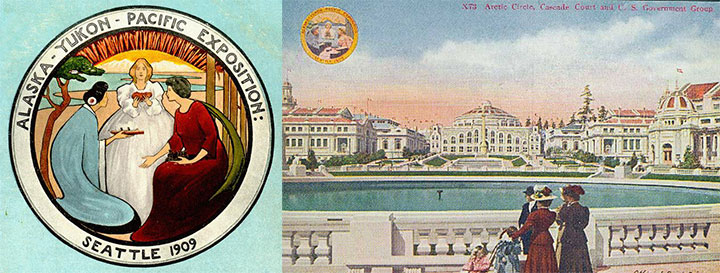

AYP and Camp Harmony images courtesy of the University of Washington Library

This is Frosh Pond in 1909, when it was called Geyser Basin (part of the so-called “Arctic Circle”), and when it was not a part of campus, but the centerpiece of the University’s predecessor, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

An event similar to a World’s Fair, the A-Y-P showcased the natural and economic resources of the Pacific Northwest with pomp and splendor. To mirror the purpose of the exposition, the fairgrounds (designed by the famous Olmsted Brothers) brought the region’s greatest symbol into stunning focus. This so-called “Rainier Vista,” culminating in the Arctic Circle, helped draw in 3.7 million visitors over the fair’s four-month duration.

Very little evidence remains of the A-Y-P fairgrounds today (much to my chagrin); the vast majority of the fair’s buildings were temporary, and even the landscape design of the modern University has all but obscured the original layout of the A-Y-P grounds. But the Arctic Circle is still there, and when you step out from behind a row of blooming cherry trees in the spring, the Rainier Vista still hits you with full force.

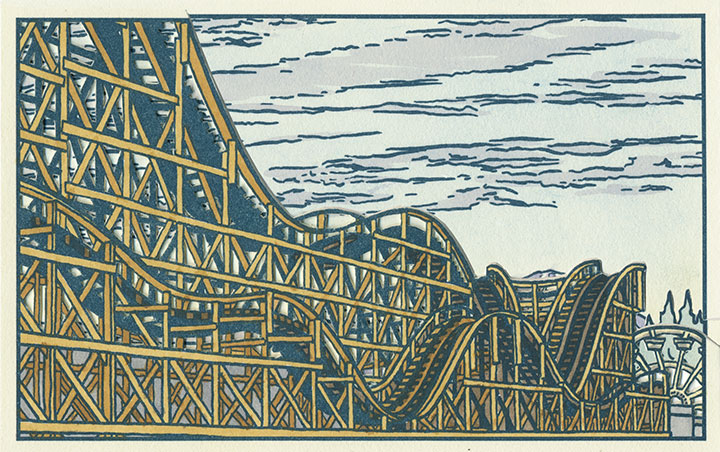

Speaking of fairgrounds, closer to T-Town is another historical remnant—this time, however, instead of a long-past event with only a marker left behind to hint at what was, these fairgrounds still hold to their original purpose today.

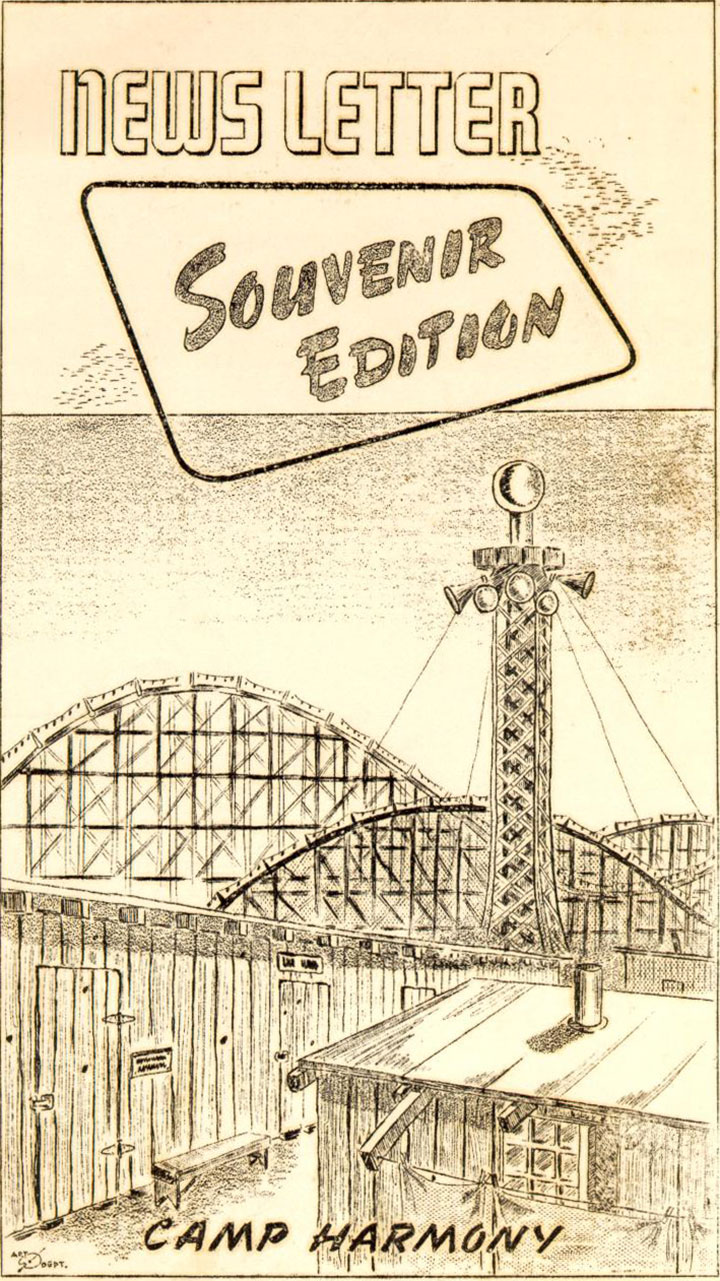

Illustration by Eddie Sato, Camp Harmony inmate and “staff” artist.

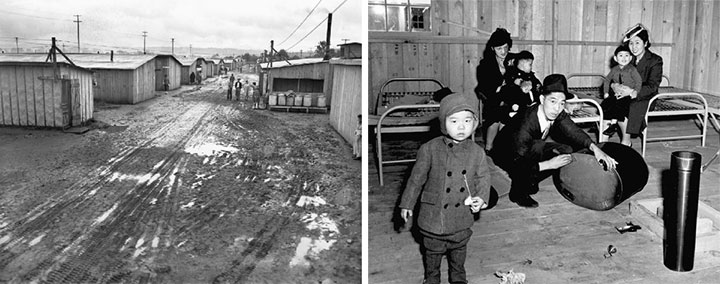

I’m talking about the Western Washington Fairgrounds in Puyallup, which are still in operation (though the event is now called the Puyallup Fair—that’s pronounced “Pew-AL-up”). In 1942, the U.S. government evicted, rounded up and imprisoned over 100,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast; the internment began with the forced migration of families living on Bainbridge Island, across the Sound from Seattle.

While they awaited the construction of permanent internment camps further inland, many Japanese Americans were sent to temporary “assembly centers” to coexist in cramped barracks with other families, often in substandard living conditions. Thousands of Washington’s interred residents were sent to the assembly center nicknamed “Camp Harmony,” hastily constructed on the fairgrounds in Puyallup, right alongside the fair’s permanent buildings and rides.

Three image flats; the mountain is almost completely hidden here.

Camp Harmony was torn down after just seven months, but the Fair continues to this day. (To my everlasting horror, the Fair’s website mentions Camp Harmony only obliquely on its “History” page—it states only that “the fairgrounds were used as a temporary shelter“—emphasis mine—during World War II. Right. A shelter where the “refugees” were imprisoned under armed guard.) And the wooden roller coaster that overshadowed Eddie Sato’s scene of the camp still stands. Now that I’ve learned the history of the place, I’ve lost my appetite for rollercoasters, funnel cakes and blue-ribbon vegetables. But the fairgrounds made for an image that dovetails eerily well with the homage to Japanese art upon which Local Conditions is founded.

Photo courtesy of Jessica Spring

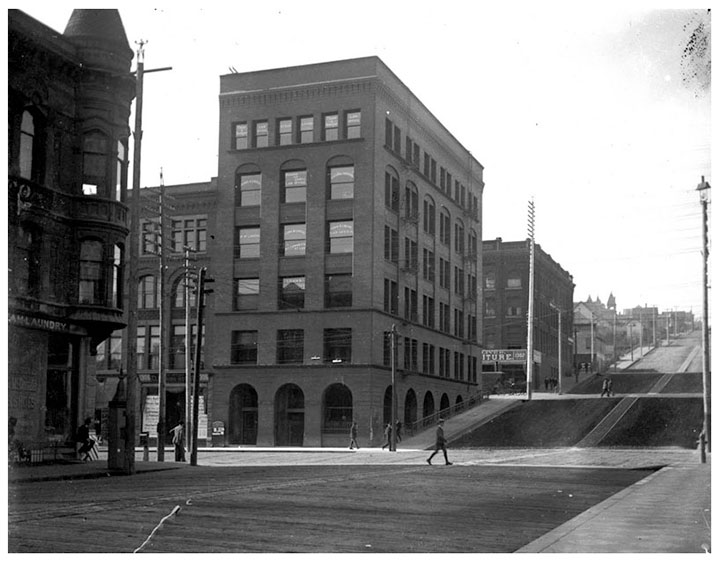

And then there’s the kind of history that unfolds right before your very eyes. Remember the Luzon building?

Two image flats; recognize the sky in the background?

Well, it was slated to be a part of the book from the very beginning—just by virtue of being a structure that caught my eye and that came with a good view of the mountain.

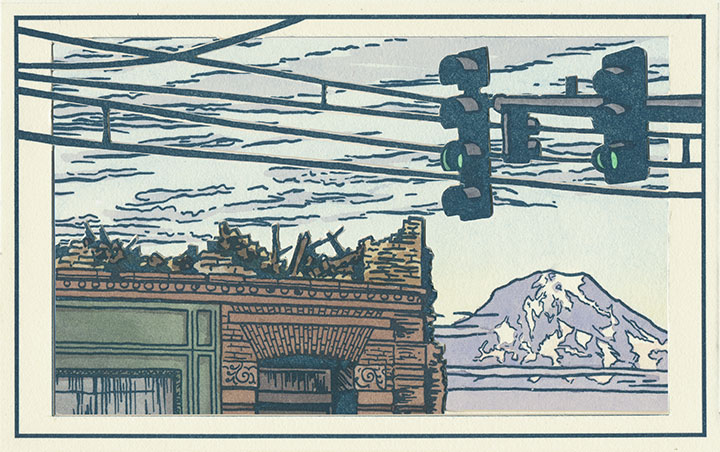

But then they knocked it down in September 2009, and suddenly I became an eye-witness, with an opportunity to document history as it happened.

Three image flats; same mountain, drastically different view.

I wish this were an imaginary scene, but it’s moments like this that the book is all about. Now you see it, now you don’t.

Postcards circa 1910. Courtesy of the Tacoma Public Library

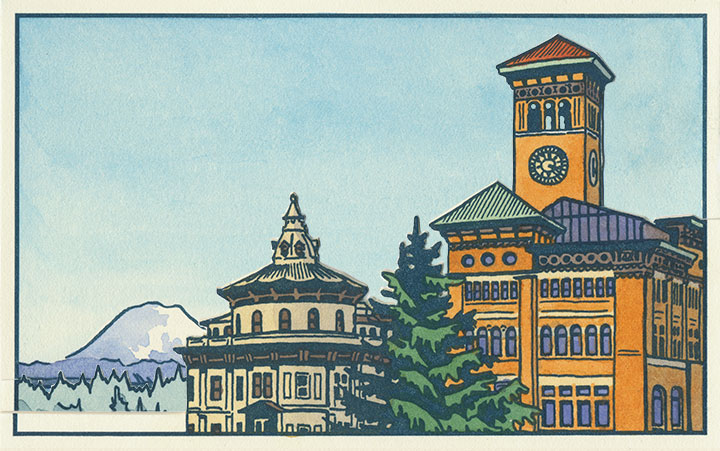

And to top it all off, it’s looking like Tacoma’s history is in danger of repeating itself. This is a postcard dated 1905, depicting what was an iconic view even then—the “Gateway to the City of Destiny.” The building on the left is the former Northern Pacific Railroad Office; on the right is Old City Hall.

Tacoma built a new city hall a few blocks away in the 1930s, but both the Northern Pacific building and Old City Hall still stand—the addition of a freeway the only major change to the site pictured. But on November 24, 2010, after an unusual cold snap, a pipe burst in Old City Hall—soaking the walls, ceilings and floors with 30,000 gallons of water. With extensive flood damage and the building owner entering foreclosure, the building faces an uncertain future. I only hope it doesn’t go the way of the Luzon.

Three image flats; there’s an individual print version in the shop.

When I started this project, I had no idea of what I was getting into. I knew that I would stumble upon some pretty fascinating history, but I never would have guessed that a fountain, some fairgrounds and a pile of bricks would draw me in so completely. But now I’m hooked—and the best part is that after all this work, I no longer feel like an outsider looking in.

This is my history now, too. For better or worse, I want to see how it all plays out.

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)

Thanks so much for posting more images from your book! It’s a boon for those of us too far away to visit the exhibit in person.