Blog

February 28th, 2013

This has not been an easy post to write—and yet in a way it’s been writing itself over and over again, for years now. To be honest, Jessica and I designed this broadside months ago, and planned to release it shortly after last year’s theater shooting in Aurora, CO. Other projects got in the way, and then the 2012 election persuaded us to table the piece for the time being.

We should have known: until there’s serious change in our society, this subject will always be hatefully relevant.

So here we are again, on the heels of yet another rash of terrible violence. But this time feels different—not only because of the sheer horror of the Newtown tragedy, but because at last, our country is having the conversation it needs to have.

At the center of the debate is the precarious balance of right and responsibility—and here’s where I need to keep from shooting my mouth off. I’ve written and deleted a hundred sentences about Jessica’s and my personal thoughts on the subject—but I have a feeling you can already guess what they are. And we also recognize that our beliefs represent just one side of our divided culture. So the thought of pontificating just wearies and saddens us; we’d much rather focus on how we might move forward, together.

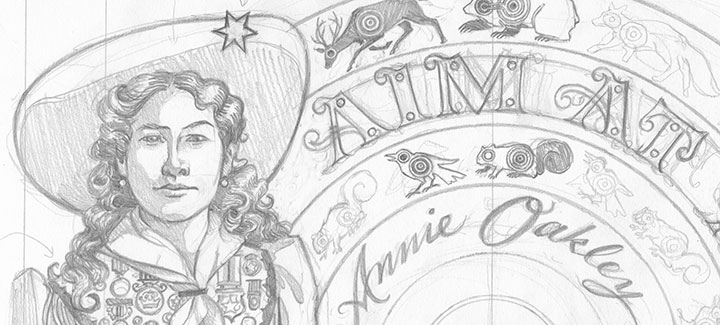

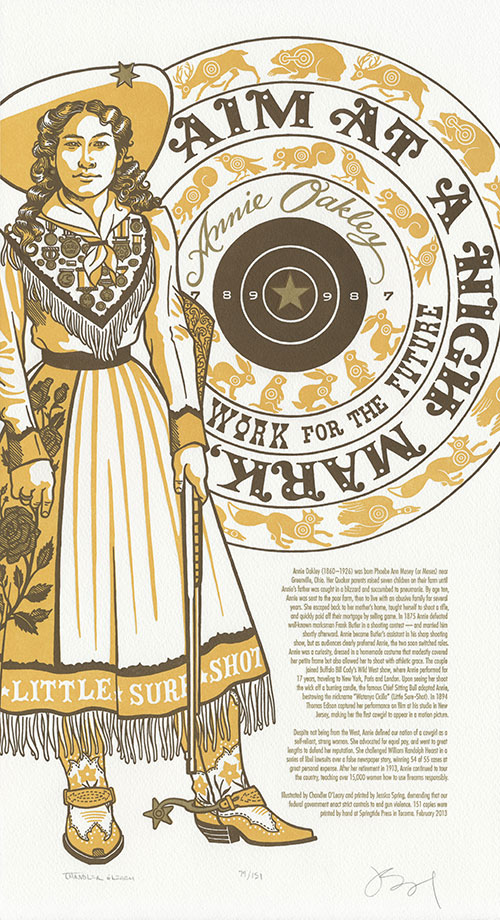

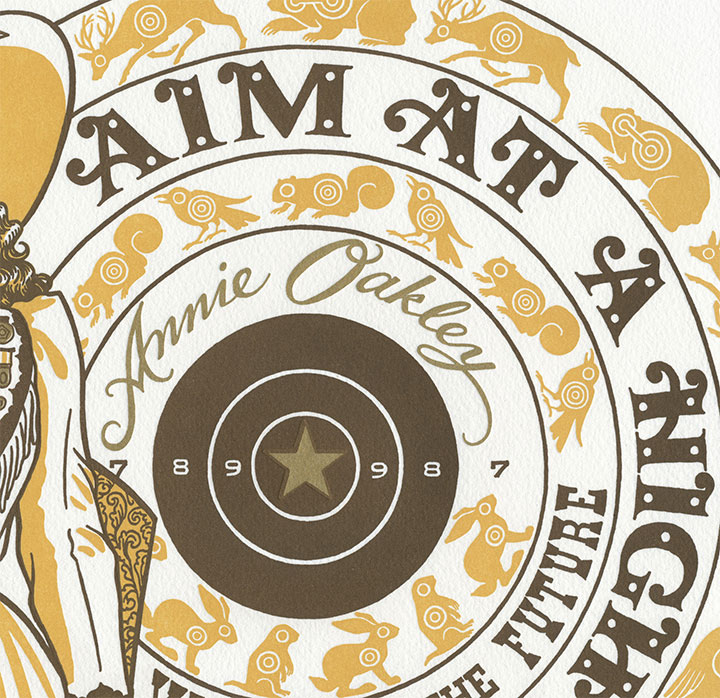

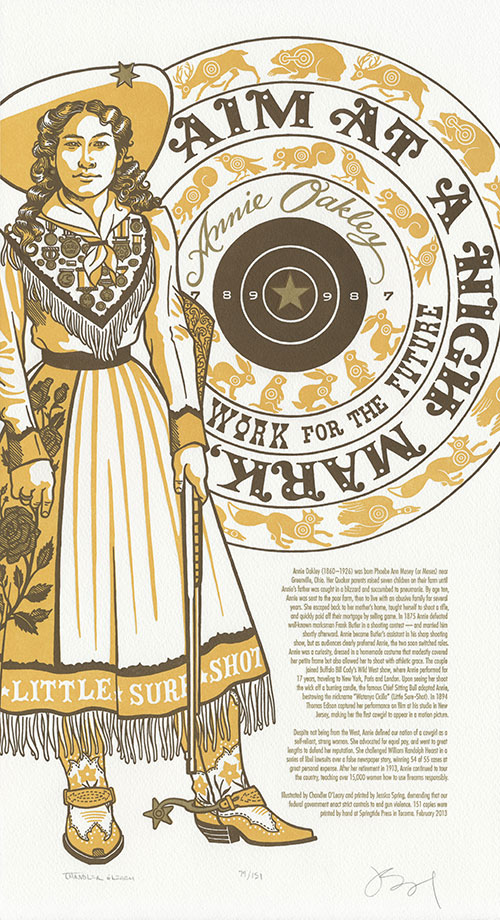

For us, that meant starting with an attempt to comprehend the other side of the debate. So in hoping to understand the love of guns many in our country share, we looked to legendary sharpshooter Annie Oakley, whose words pierce the heart of the matter:

Aim at a high mark, work for the future.

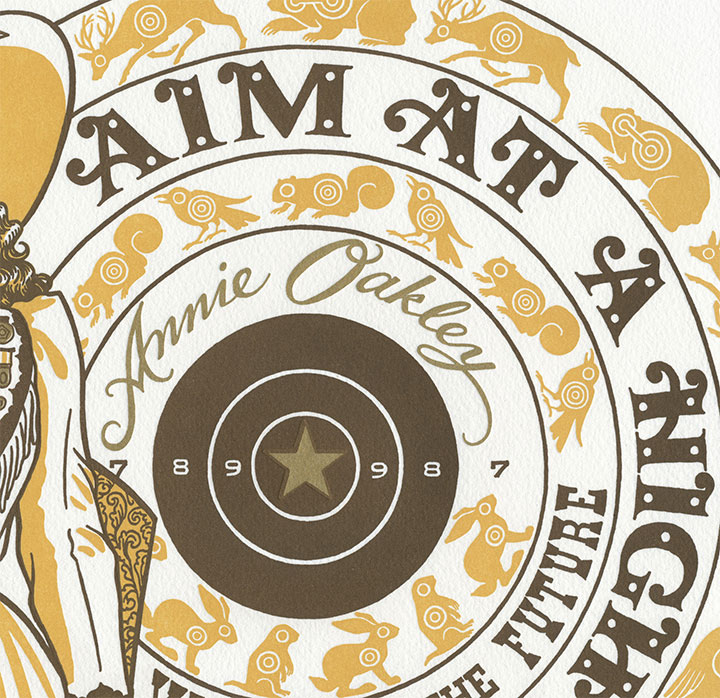

This piece is a stark, steely contrast to the bright colors and detailed embellishments of the rest of the series. Annie stands her ground beside a blazing metallic bullseye, representing the golden target of sanity amid the scatter-shot opinions and half-cocked sniping of those on the extremist fringes. And let me tell you: there’s real gold in that ink. Jessica mixes her own formula—maybe it’ll shine all the brighter, and help steady our collective aim.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Gun Shy: No. 17 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 151

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

The edition number we choose for each print in our series is always significant in some way—whether we call attention to it or not. In the case of Gun Shy, we’ve created an edition of 151 prints to represent each person injured or killed in a shooting rampage in 2012. In light of that sobering number, we’ve chosen to donate a portion of our proceeds to Demand A Plan. A campaign of Mayors Against Illegal Guns, Demand a Plan is a national, bipartisan coalition working to make America’s communities safer by keeping illegal guns out of dangerous hands.

Colophon reads:

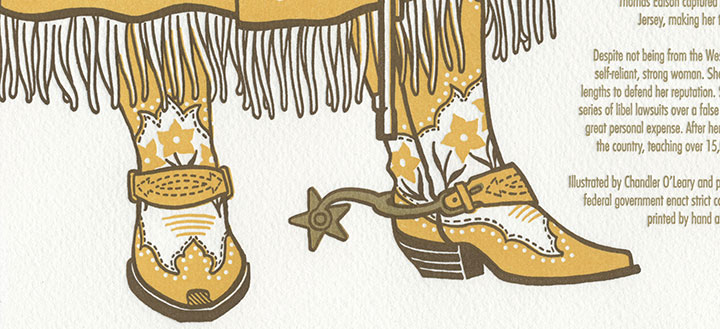

Annie Oakley (1860 – 1926) was born Phoebe Ann Mosey (or Moses) near Greenville, Ohio. Her Quaker parents raised seven children on their farm until Annie’s father was caught in a blizzard and succumbed to pneumonia. By age ten, Annie was sent to the poor farm, then to live with an abusive family for several years. She escaped back to her mother’s home, taught herself to shoot a rifle, and quickly paid off their mortgage by selling game. In 1875 Annie defeated well-known marksman Frank Butler in a shooting contest — and married him shortly afterward. Annie became Butler’s assistant in his sharp shooting show, but as audiences clearly preferred Annie, the two soon switched roles. Annie was a curiosity, dressed in a homemade costume that modestly covered her petite frame but also allowed her to shoot with athletic grace. The couple joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show, where Annie performed for 17 years, traveling to New York, Paris and London. Upon seeing her shoot the wick off a burning candle, the famous Chief Sitting Bull adopted Annie, bestowing the nickname “Watanya Cicilla” (Little Sure-Shot). In 1894 Thomas Edison captured her performance on film at his studio in New Jersey, making her the first cowgirl to appear in a motion picture.

Despite not being from the West, Annie defined our notion of a cowgirl as a self-reliant, strong woman. She advocated for equal pay, and went to great lengths to defend her reputation. She challenged William Randolph Hearst in a series of libel lawsuits over a false newspaper story, winning 54 of 55 cases at great personal expense. After her retirement in 1913, Annie continued to tour the country, teaching over 15,000 women how to use firearms responsibly.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, demanding that our federal government enact strict controls to end gun violence.

Available now in the Dead Feminists shop.

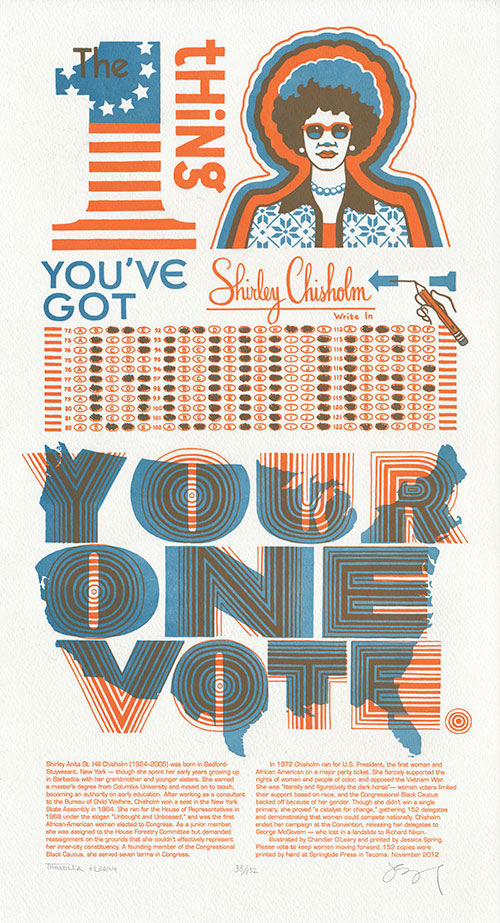

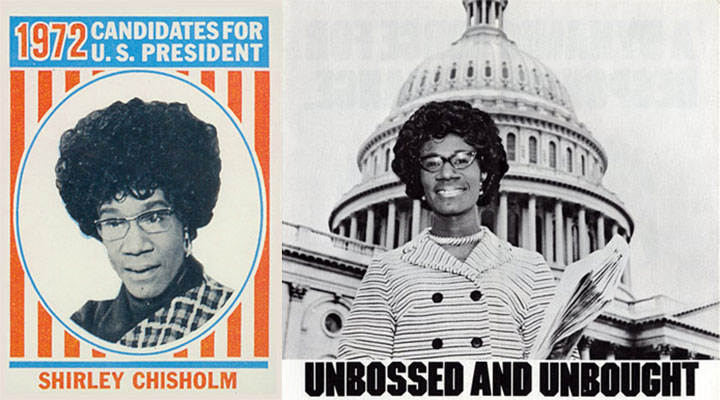

November 5th, 2012

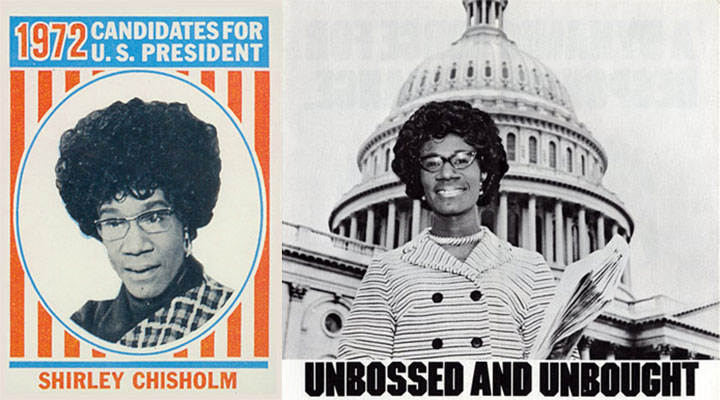

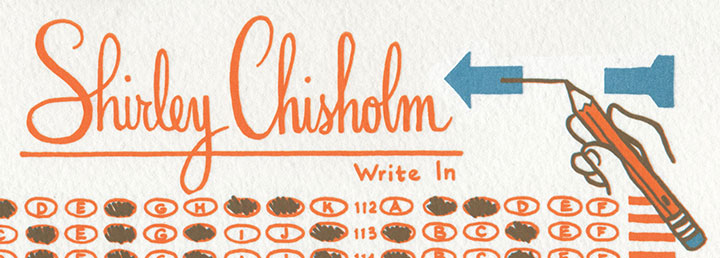

If you have any sort of link to the outside world (television, radio, internet access, newspaper, mailbox), chances are you’ve been unable to escape this year’s deluge of advertising, chatter and glossy-printed recycling fodder—all centered around this coming Tuesday. It’s enough to have even four-year-olds throwing up their hands in frustration. Jessica and I, however, have spent many hours sifting through election material—1972 election material, I mean. To remind us of what’s really important this year (and every year), we turned to the woman who help paved the way for our current President.

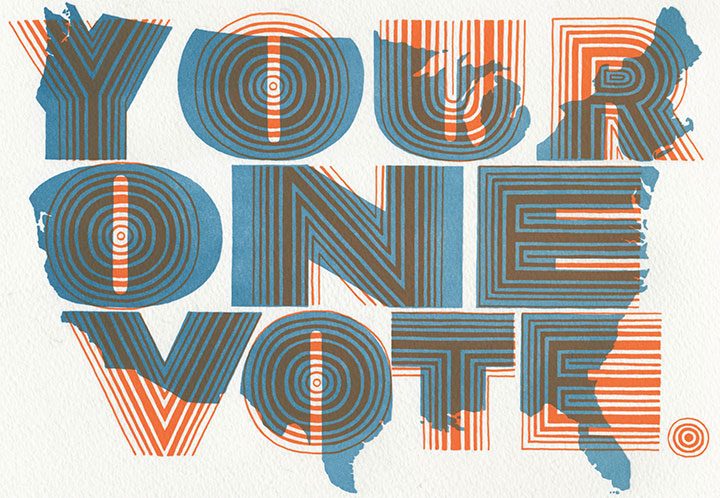

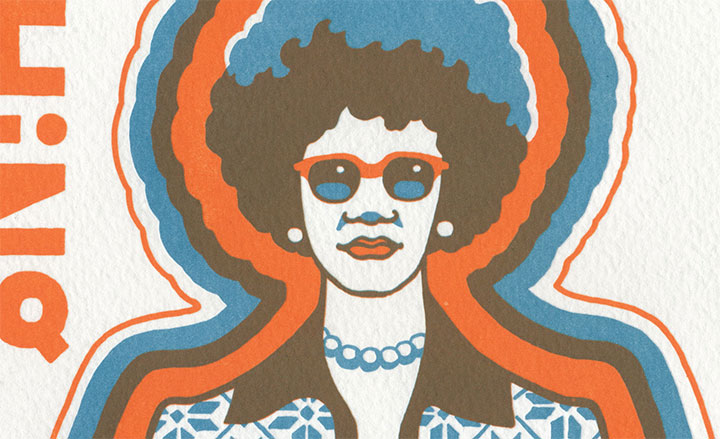

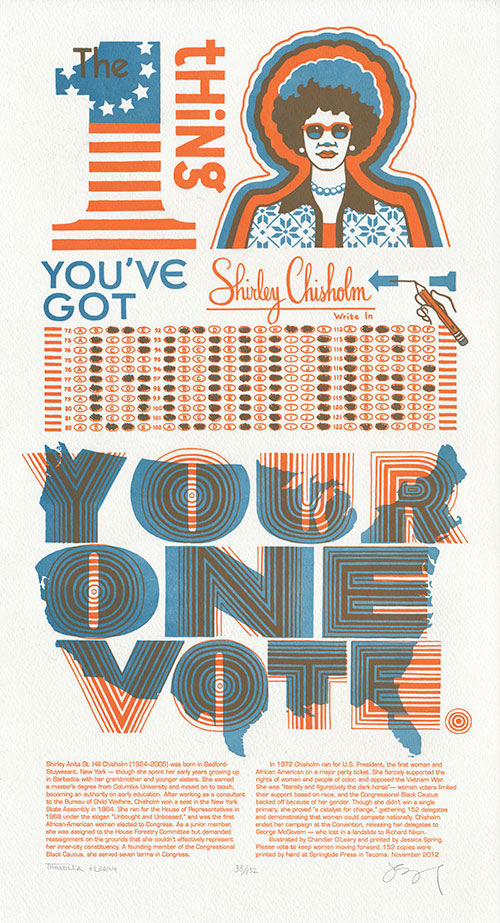

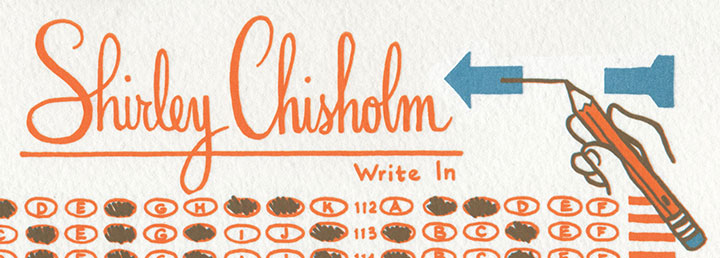

The one thing you’ve got going: your one vote. —Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Chisholm was one of fifteen Presidential candidates in 1972. It was a volatile time: the Vietnam War was the center of public discord; movements for civil rights and gender equality were major issues around the western world; and the race came on the heels of the 1968 race—one of the bloodiest election years in American history.

Shirley knew she was a long shot; she even referred to herself as “literally and figuratively the dark horse.” Yet she also knew that to run for President, all that was required was to be a natural-born U.S. citizen of at least 35 years of age. There was nothing in there about being male or Caucasian—and as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, she was at least as qualified as her fellow candidates. So she ran, because it was her right, and because she knew that if she played it smart and started winning delegates, she’d have some power to leverage.

Shirley sought to create a truly representative government. Rather than a cookie-cutter set of interchangeable politicians running the country, she envisioned an America where each region, economic sector and ethnic group elected one of its own to office. She wanted to see a woman heading the Department of Education & Welfare; a Native American in charge of the Department of the Interior. And as a freshman Congresswoman she was assigned to the House Forestry Committee but refused to serve—how would forest stewardship or agricultural bills represent New York’s inner-city 12th Congressional District?

She also saw her office as an opportunity to encourage women—especially women of color—to get involved in politics. Every member of her staff was a woman, half of them African-American. To say the least, her very presence made her fellow legislators nervous—and on top of everything else, she was probably the only woman of color in the whole country who made the exact same salary as her white male colleagues. (Heck, for people like Yvette Clarke or Barbara Lee, that’s probably still true for the most part. How depressing is that?)

On the national political stage, however, her race and gender were two strikes against her. She gathered support from the National Organization for Women, but when the time came for NOW to officially endorse a candidate, their squeamishness over the possibility of a black nominee overcame their lip service. And the Black Congressional Caucus, of which Shirley was a founding member, threw her under a bus because they couldn’t bring themselves to support a female candidate. To me, that’s the most interesting thing—Shirley Chisholm always said she faced far more discrimination over her gender than the color of her skin.

Still, though she had to battle opposition and prejudice from all sides, she worked to bring people of all stripes together. When her opponent George Wallace (yes, that George Wallace—Mr. “Segregation Now, Segregation Tomorrow, Segregation Forever”) was wounded in an assassination attempt, Shirley visited him in the hospital. They were the ultimate Odd Couple: years later Wallace used his clout among Southern congressmen to help Shirley pass a bill giving domestic workers the right to a minimum wage.

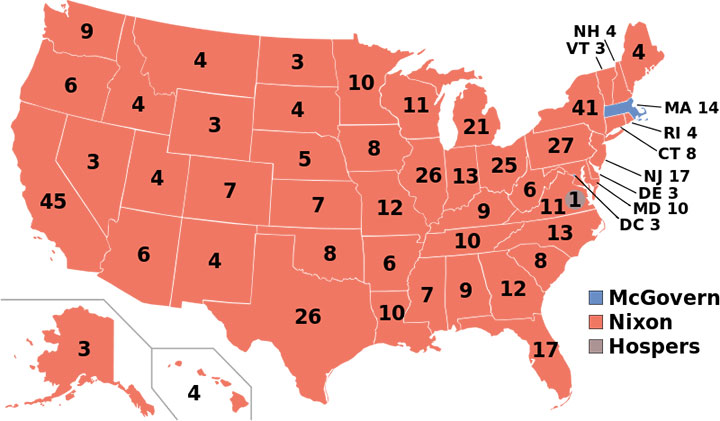

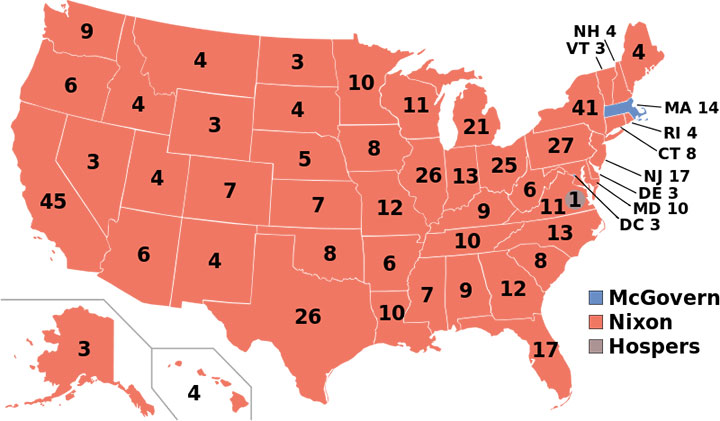

In the end, though she gathered 152 delegates, she knew she’d never snag the Democratic nomination. So she conceded to George McGovern—who went on to win just one state (Massachusetts) in the 1972 Presidential election. Take a look at the electoral college map for that year:

That’s a whole lotta red.

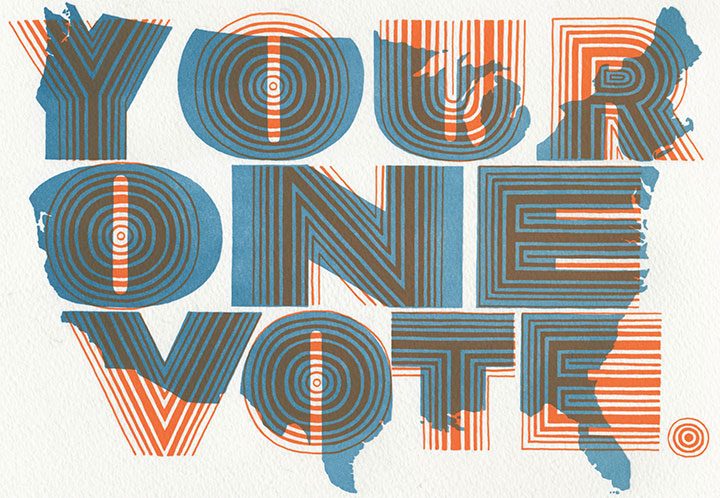

And since this election season marks the fourth anniversary of our series, that map was the starting point for Keep the Change, our new Dead Feminist broadside. I redrew the map in blue, and from there we crafted a period homage to Shirley’s impeccable style and substance.

The 12th Congressional District was one of the areas hardest hit last week by Hurricane Sandy. While the immediate recovery efforts in the city are crucial, we also recognize the importance of serving a community long after the disaster relief efforts have ended. So to help continue Shirley’s long-term service to her home city, we’ll be donating a portion of our proceeds to Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration, the nation’s first non-profit community development corporation. Restoration partners with residents and businesses to improve the quality of life of Central Brooklyn by fostering economic self sufficiency, enhancing family stability, promoting the arts and culture and transforming the neighborhood into a safe, vibrant place to live and work.

In the meantime, let’s do what Shirley did best—cast our vote, and keep fighting the good fight.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Keep the Change: No. 16 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 152

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm (1924–2005) was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, New York — though she spent her early years growing up in Barbados with her grandmother and younger sisters. She earned a master’s degree from Columbia University and moved on to teach, becoming an authority on early education. After working as a consultant to the Bureau of Child Welfare, Chisholm won a seat in the New York State Assembly in 1964. She ran for the House of Representatives in 1968 under the slogan “Unbought and Unbossed,” and was the first African-American woman elected to Congress. As a junior member, she was assigned to the House Forestry Committee but demanded reassignment on the grounds that she couldn’t effectively represent her inner-city constituency. A founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, she served seven terms in Congress.

In 1972 Chisholm ran for U.S. President, the first woman and African American on a major party ticket. She fiercely supported the rights of women and people of color, and opposed the Vietnam War. She was “literally and figuratively the dark horse”— women voters limited their support based on race, and the Congressional Black Caucus backed off because of her gender. Though she didn’t win a single primary, she proved “a catalyst for change,” gathering 152 delegates and demonstrating that women could compete nationally. Chisholm ended her campaign at the Convention, releasing her delegates to George McGovern — who lost in a landslide to Richard Nixon.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring. Please vote to keep women moving forward.

Available now in the Dead Feminists shop!

June 13th, 2012

If you happen to live in Washington state, you can’t help but notice that love is in the air. It’s not quite what you think, though—rather than turtledoves and cupids flying around, the breeze is carrying ballot petitions and angry voices.

Though Washington became the seventh U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage earlier this year, opponents forced a voter referendum to decide the issue this November. So while we’d rather just toast our friends and their families, we’ve got to put up our dukes first.

Already tempers are running high, and everyone seems to be up in arms—it’s total anarchy out there. So we thought, who better to talk to than an anarchist?

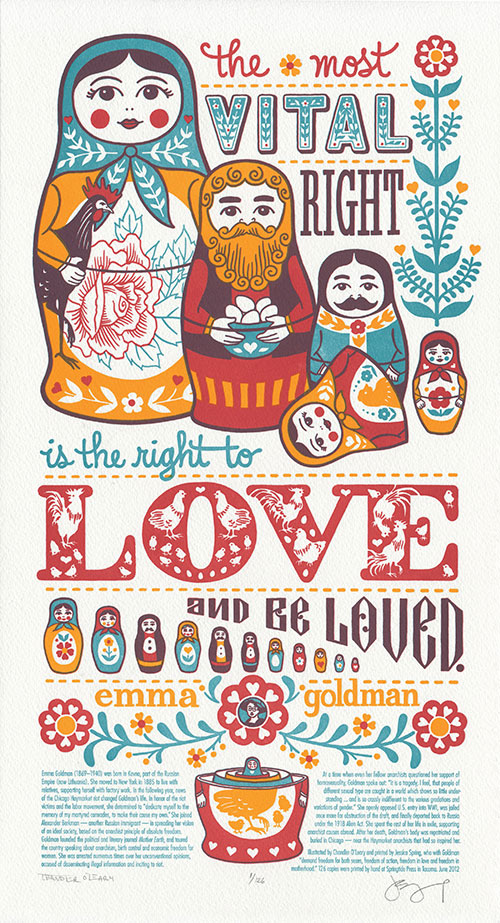

The most vital right is the right to love and be loved. —Emma Goldman

Huh. Pretty down-to-earth for an anarchist, actually. Especially if you consider some of the other things Emma’s said in the past.

I think that if we could somehow put all the ladies we’ve featured previously into a room together, they might end up killing each other (good thing they’re already dead, eh?). They all had such different ideologies and passions that I can’t imagine all fourteen of them agreeing on any one thing. But I’m fairly sure they’d be united over Emma—in thinking she was a complete weirdo, that is. (Sorry, Emma.)

Yet for all her outlandish creeds and fierce opinions, her thoughts on families, love and motherhood cut straight to the heart of the matter. And that’s what drew us to her.

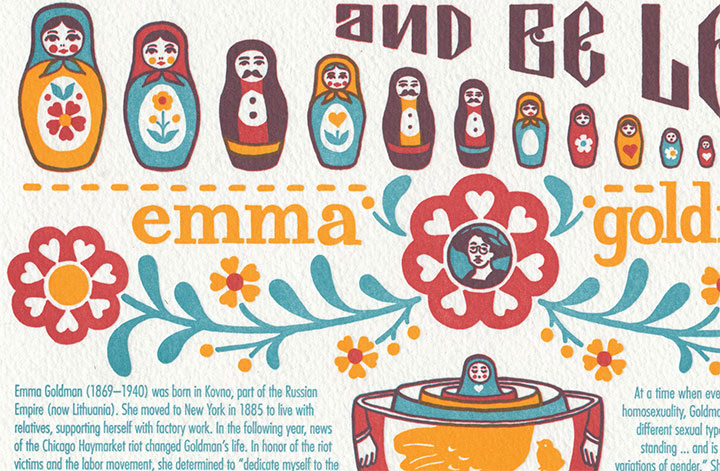

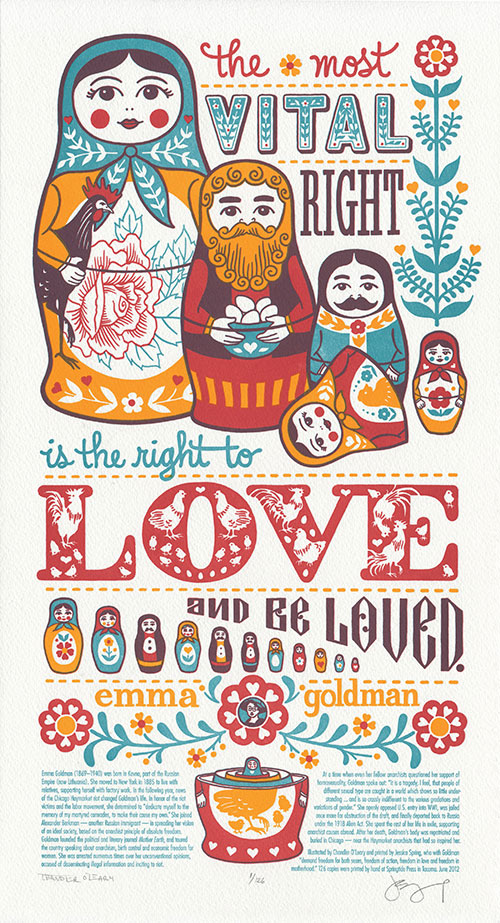

To pay homage to Emma’s folksy words, we turned to folk art for inspiration. (Get out your grandma’s Pyrex and raise a glass!) Love Nest is dominated by a lively brood of nesting matryoshka dolls. Each individual is different, but together they complete the picture of a nurtured, multicolor family. Roosters, hens and chicks complete the flock waiting for the next generation to hatch as Emma’s words stitch the family together.

To support the diversity nested within every family, we’ll be donating a portion of the proceeds to both the Rainbow Center and Oasis Youth Center, right here in T-town. The Rainbow Center is dedicated to eliminating discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender. Oasis is a drop-in support center dedicated to the needs of GLBTQ youth ages 14-24.

Speaking of chickens, there’s another tribute hiding in here—a nod to the very first matryoshka doll ever made.

This might well be the most difficult piece we’ve tackled yet. Beyond the challenges of marrying (no pun intended) the views of a 19th-century fringe activist to modern-day social issues, we also had some seriously precarious business on the technical side. Those of you who are into the nitty gritty details of letterpress may know that each print color requires a separate plate, a separate pass on press. We’ve got four colors in the final result, but because of the tricky magic of translucent inks, there’s actually only three plates/three passes here. The red and teal mix to make brown—which means that the registration (alignment) of each plate had to match up just right.

I was expecting Jessica to throttle me when I showed her the color separations, but as usual, she barely even batted an eye: “Yeah, we can do that.”

Or maybe she just knows me so well now that she’s expecting the crazy.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Love Nest: No. 15 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 126

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Emma Goldman (1869 – 1940) was born in Kovno, part of the Russian Empire (now Lithuania). She moved to New York in 1885 to live with relatives, supporting herself with factory work. In the following year, news of the Chicago Haymarket riot changed Goldman’s life. In honor of the riot victims and the labor movement, she determined to “dedicate myself to the memory of my martyred comrades, to make their cause my own.” She joined Alexander Berkman—another Russian immigrant—in spreading her vision of an ideal society, based on the anarchist principle of absolute freedom. Goldman founded the political and literary journal “Mother Earth,” and toured the country speaking about anarchism, birth control and economic freedom for women. She was arrested numerous times over her unconventional opinions, accused of disseminating illegal information and inciting to riot.

At a time when even her fellow anarchists questioned her support of homosexuality, Goldman spoke out: “It is a tragedy, I feel, that people of different sexual type are caught in a world which shows so little understanding … and is so crassly indifferent to the various gradations and variations of gender.” She openly opposed U.S. entry into WWI, was jailed once more for obstruction of the draft, and finally deported back to Russia under the 1918 Alien Act. She spent the rest of her life in exile, supporting anarchist causes abroad. After her death, Goldman’s body was repatriated and buried in Chicago—near the Haymarket anarchists that had so inspired her.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, who with Goldman “demand freedom for both sexes, freedom of action, freedom in love and freedom in motherhood.”

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

November 15th, 2011

It’s hard to ignore the news of protests, ahem, occupying the attention of cities around the world—of the many and diverse thousands of people unified under one simple, yet infinitely faceted mantra. As members of the, well, vast majority of folks without any real political or financial clout in the world, Jessica and I can get behind their message—but that’s not so much the point. What really amazes us is that with a little tenacity and strength in numbers, the powerless can suddenly become very powerful, indeed.

It made us think of a woman who, despite having a famous sibling, would have disappeared into obscurity but for the simple act of picking up a pen.

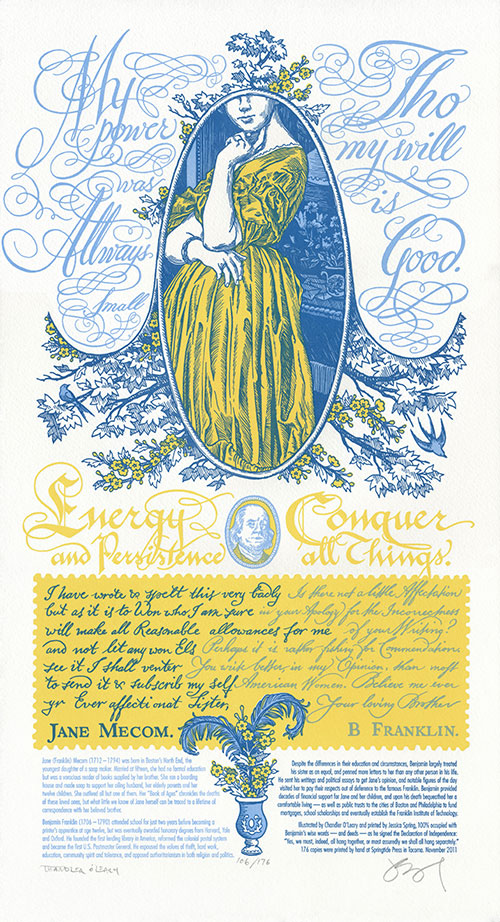

My power was allways small tho my will is good. —Jane Mecom

Jane’s eminent brother, on the other hand, had a little more faith:

Energy and persistence conquer all things. —Benjamin Franklin

Jane had both energy and persistence in spades—although we marvel at how she managed it, with twelve kids, a family business and a house perpetually full of boarders to occupy her attention. Yet of Benjamin’s sixteen siblings, Jane is the only one whose story has survived the 200+ years since her death—and all because she committed her thoughts to paper. So in honor of Ben and Jane’s relationship, and in solidarity with those who find the strength to speak up, we present our first dual Dead Feminist broadside, Signed, Sealed, Soapbox.

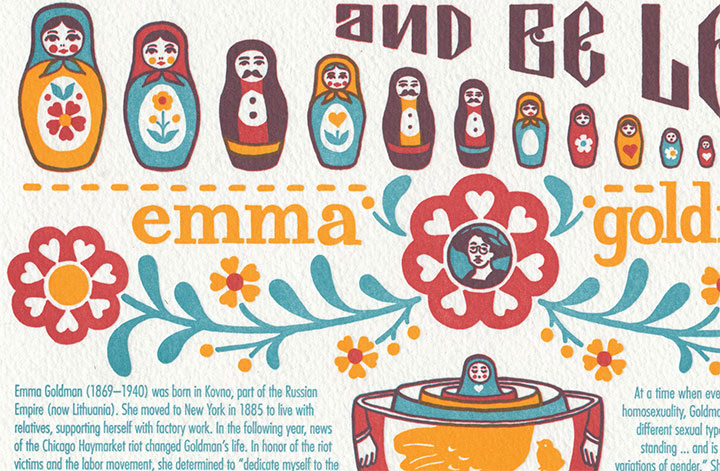

Since this is also our first print that features a cameo from a male Dead Feminist (nope, you don’t have to be female to be a feminist), we thought it deserved a little something extra. So we set it up like a conversation—or in this case, a written correspondence. Besides, there was just so much historical ground to cover—even condensing the information to a blog post is a challenge, let alone plucking two sentences from a lifetime of dialogue. (If you haven’t already guessed, this post is a long one. Grab a cuppa if you dare to settle in!)

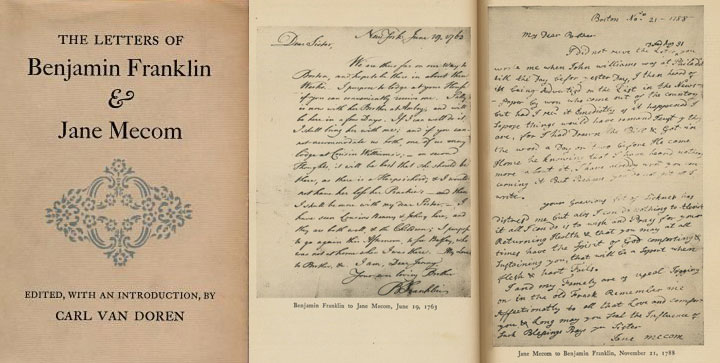

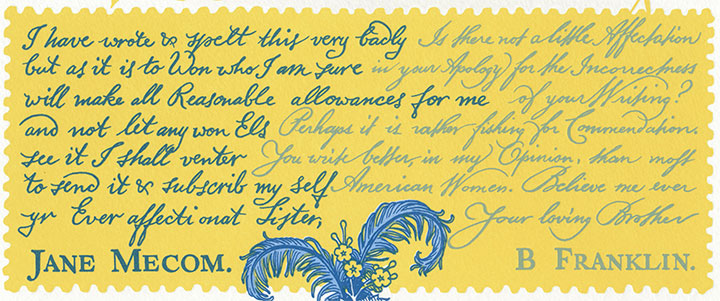

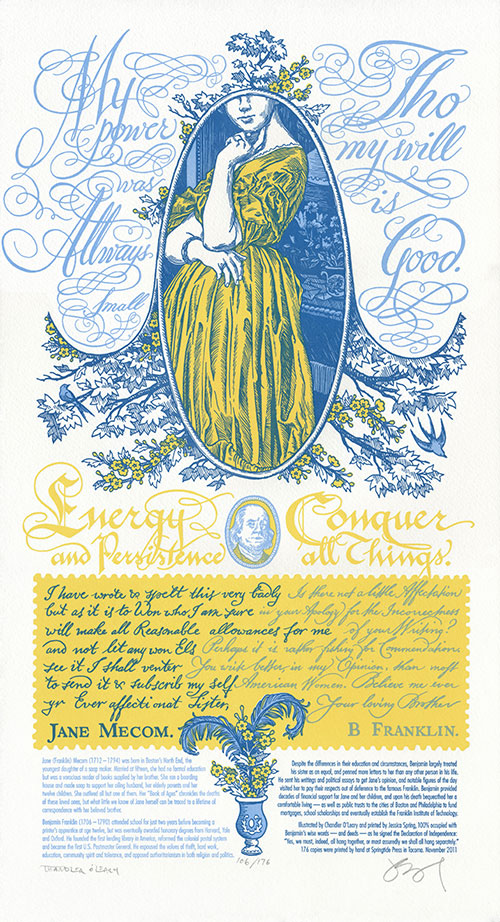

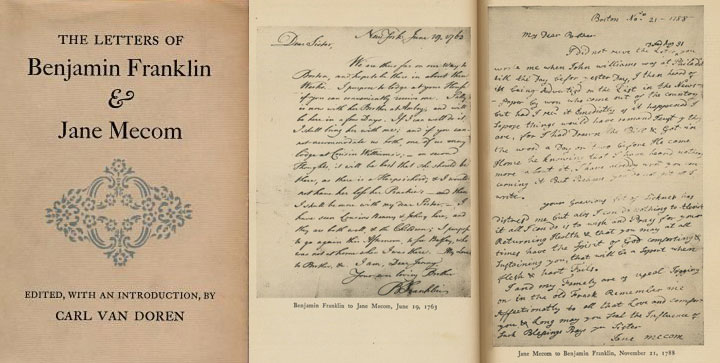

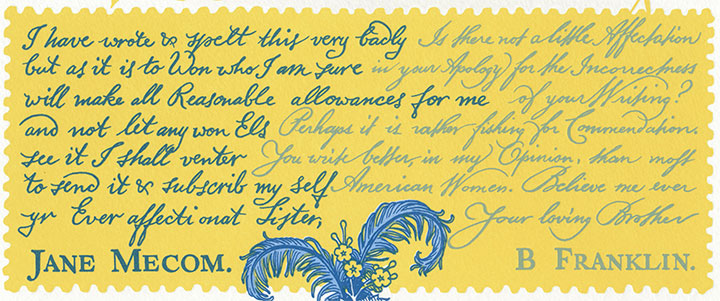

What first sent us down the Jane Mecom rabbit hole was an article about her in the New York Times, written by Jill Lepore. Lepore’s words sent me searching for more information, and I found it buried in the stacks of my local public library. I uncovered an obscure tome: The Letters of Benjamin Franklin and Jane Mecom, by Carl van Doren. The book chronicles their entire surviving correspondence—98 letters in all, printed in full. I was a little worried that the writing style of the day would make even skimming for quotes a chore—but in truth, I couldn’t put it down. It was like peering into the lives of any two ordinary people who happened to care for each other very much. There’s humor, and worried advice, and gossip, and gentle sarcasm, and the occasional scolding (usually on Jane’s part) when one or the other let too much time pass between letters. Most of all, there’s love—it’s there on every page. After all of that, we couldn’t just limit the broadside to a couple of one-liners. So the quotes are accompanied by excerpts from their actual letters, each calligraphed as closely as possible to Ben and Jane’s actual handwriting. Even the spelling errors and colonial-era grammar are intact; we figured it was better not to mess with history.

Jane’s excerpted letter:

I have wrote & spelt this very badly but as it is to Won who I am sure will make all Reasonable allowances for me and will not let any won Els see it I shall venter to send it & subscrib my Self yr Ever affectionat Sister, Jane Mecom.

Ben’s reply:

Is there not a little Affectation in your Apology for the Incorrectness of your Writing? Perhaps it is rather fishing for Commendation. You write better, in my Opinion, than most American Women. Believe me ever Your loving Brother, B. Franklin.

There are few Founding Fathers more famous than Ben Franklin, but Jane was somewhat of a mystery. What we do know is that she had a very different life than her illustrious brother. Thanks to the simple fact of having been born female, her youth was spent having babies rather than obtaining an education. Her life was marked with misfortune, poverty and the deaths of nearly everyone she loved. Yet through it all she craved knowledge, and read everything she could get her hands on. She was a skilled craftsperson, making the famed Franklin Crown Soap and teaching the trade to others. And she followed her brother’s career with pride—and he supported her in return, both financially and emotionally.

The Tailor and I spent time in both Boston and Philadelphia this summer—ye olde stomping grounds for Doctor Franklin. I had the library book of letters with me on the trip, so their words lent an interesting depth to our wanderings.

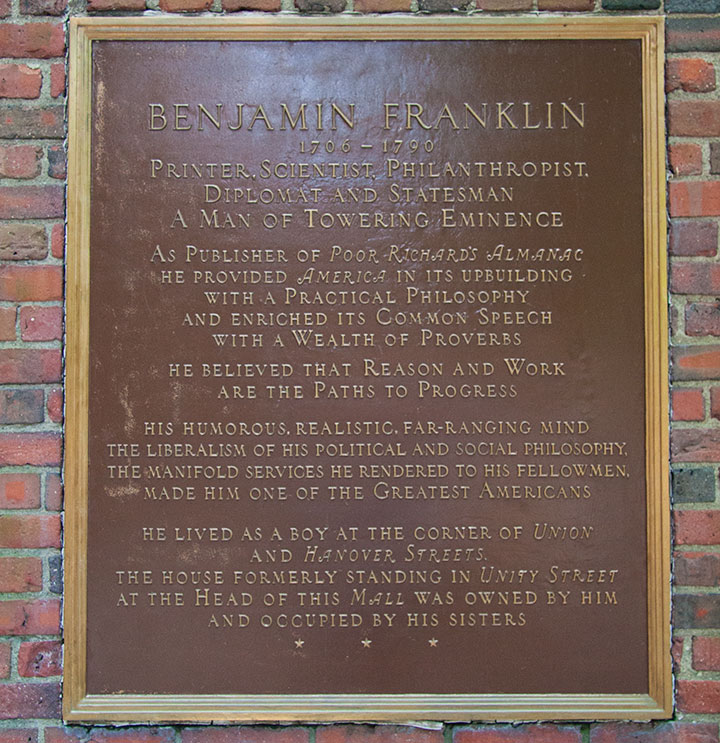

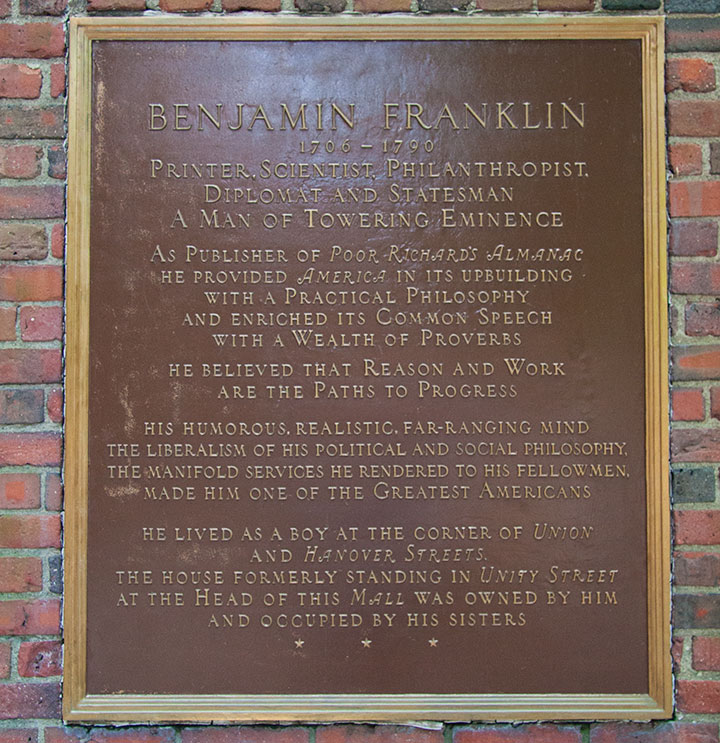

Boston is one of my hometowns, so it was there that I did the most digging. And it turned out that digging was necessary. Ben’s presence is everywhere in Philly, but in Boston, with so many Revolutionary War heroes to honor there, the Franklin family’s presence is far more subtle. And Jane? Well, she’s almost nowhere to be found.

Almost.

This plaque is all that’s left of the house where Jane spent all her life. It was knocked down to make room for a memorial to Paul Revere. The plaque does mention her briefly, but not by name. Another hazard of being female in the eighteenth century, I suppose.

But Jane lived through the Revolutionary war—in fact, as a resident of the North End, her home was right in the thick of it. In 1775 she fled the British-occupied city and took refuge with friends near Providence, Rhode Island. There, Ben came to rescue her. He took her to Philadelphia, where she spent a year with him before returning to a liberated Boston. While that year was full of turmoil and uncertainty for the citizens of the new United States, 1776 was quite possibly the best year of Jane’s life. For the first time in ages, she could bask in her beloved brother’s company—and he made time for her despite being busy with other things (you know, like founding our country)—and as the honored guest she was largely free from work and family duty.

As far as I can tell, it was also the last time she ever laid eyes on him. Visiting at all was a rare treat—between Ben’s high-profile career and the then-formidable distance between Boston and Philadelphia, it was impossible for them to visit one another more than a handful of times in their entire lives. And since it would have taken weeks for a letter to cross five colonies, and months to traverse the ocean to reach Ben in France, it’s a wonder they remained as close as they did all their lives. Lends a whole new meaning to “snail mail,” doesn’t it?

Signed, Sealed, Soapbox is illustrated with the sweeping curves of ornate penmanship and the detailed linework of colonial engravings. A faux-bois forest of branches and flowers resembles the printed toile fabrics of the day. The swoops and swirls of the calligraphy rest in stately Wedgwood blue (complimented by a telltale vase at the bottom!), while Ben and Jane’s correspondence occupies a buttery yellow letter edged like a vintage postage stamp.

And though there is no surviving likeness of Jane Mecom, she deserves so much more than the portrait of a Jane Doe. Instead, she is made in the image of The Comtesse d’Haussonville by French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Ben was the best big brother Jane could have asked for. So in honor of his positive influence, we’ll be donating a portion of our proceeds to the Puget Sound chapter of Big Brothers, Big Sisters—an organization dedicated to providing children facing adversity with mentor relationships that change their lives for the better, forever.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Signed, Sealed, Soapbox: No. 14 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 176

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Jane (Franklin) Mecom (1712 – 1794) was born in Boston’s North End, the youngest daughter of a soap maker. Married at fifteen, she had no formal education but was a voracious reader of books supplied by her brother. She ran a boarding house and made soap to support her ailing husband, her elderly parents and her twelve children. She outlived all but one of them. Her “Book of Ages” chronicles the deaths of these loved ones, but what little we know of Jane herself can be traced to a lifetime of correspondence with her beloved brother.

Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790) attended school for just two years before becoming a printer’s apprentice at age twelve, but was eventually awarded honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale and Oxford. He founded the first lending library in America, reformed the colonial postal system and became the first U.S. Postmaster General. He espoused the values of thrift, hard work, education, community spirit and tolerance, and opposed authoritarianism in both religion and politics.

Despite the differences in their education and circumstances, Benjamin largely treated his sister as an equal, and penned more letters to her than any other person in his life. He sent his writings and political essays to get Jane’s opinion, and notable figures of the day visited her to pay their respects out of deference to the famous Franklin. Benjamin provided decades of financial support for Jane and her children, and upon his death bequeathed her a comfortable living — as well as public trusts to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia to fund mortgages, school scholarships and eventually establish the Franklin Institute of Technology.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, 100% occupied with Benjamin’s wise words — and deeds — as he signed the Declaration of Independence: “Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Available now in our new Dead Feminists shop!

August 10th, 2011

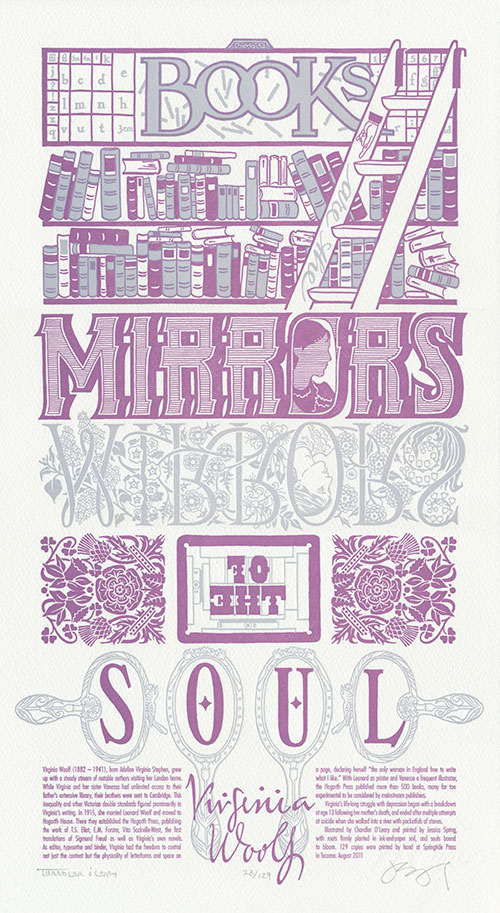

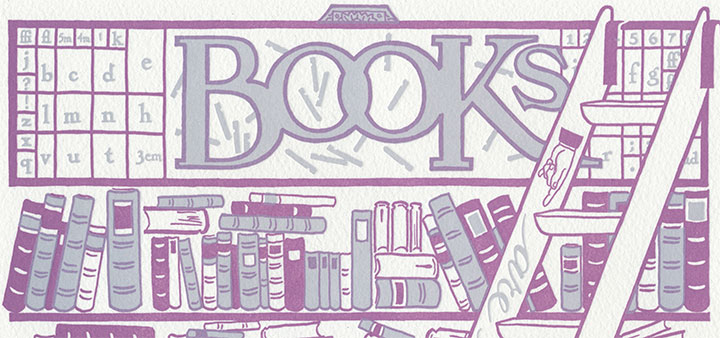

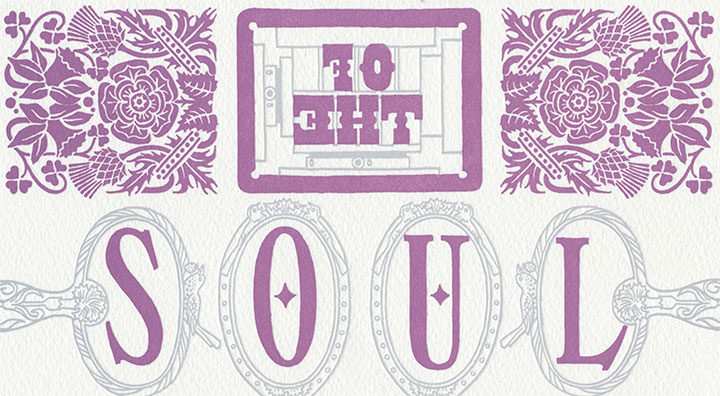

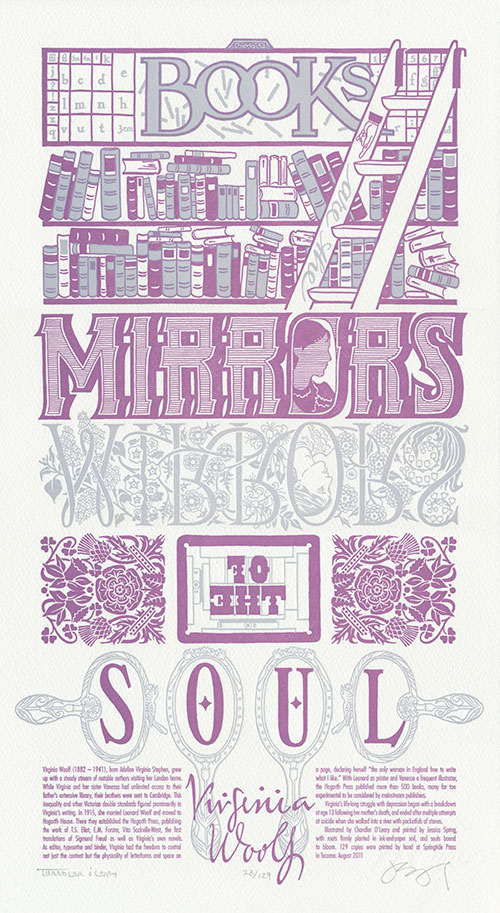

Jessica and I are back from Asheville, with fresh memories of hazy heat and sweltering summer on our minds. Back home in Washington, however, we’re having the kind of chilly summer that demands a cozy sweater, a cup of tea and time spent curled up with a good book (and thanks to our sojourn in the South, we want to do that curling up in a rocking chair!). The news of bankrupt corporate bookstores and dire warnings of an electronic apocalypse swirl around us as we read. Yet the world contained between a pair of unassuming cloth covers begs to differ. The e-readers and tech gadgets of the world are carving out their niche—but we breathe a contented sigh at the simple truth that books are here to stay. In honor of the tactile power of fresh ink and crisp pages, we’ve shared our composing stick with a fellow letterpress printer, the celebrated English author Virginia Woolf:

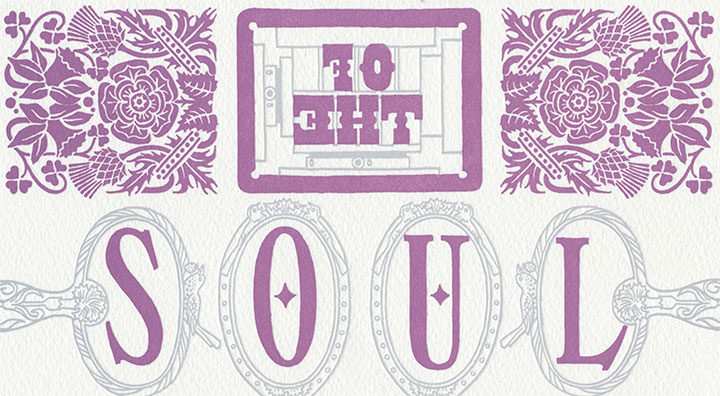

Books are the mirrors of the soul.

Paper Chase is teeming with letterpress references and the tools of Virginia’s trade. A type case helps sort the problem of minding one’s Ps and Qs, while an inked-up chase (an inside joke for our fellow printers) is locked and loaded and ready to print. Above that is a staple of any writer: a messy bookshelf overflowing with stacked volumes.

Reflected in the mirror of Virginia’s work is the beauty—and sadness—that veils her prose. Ghostly silver ink floats like a lingering afterimage, and an ethereal garden blooms from spectral soil. Lilacs and lilies, thistles and honeysuckles take root—each planting a seed of meaning from the Victorian tome The Language of Flowers. Do a little digging and discover layers of rich symbolism that reveal the woman behind the words.

And for those of you who are into historical printers like we are, there’s an extra little goody hidden in the hand mirrors: a nod to another great Victorian printer and Renaissance-person, William Morris. And if you know your floral national emblems (hint: look for the rose!), you’ll discover a link to both Virginia’s and William’s homeland.

We’ll be donating a portion of our proceeds to the Independent Publishing Resource Center in Portland, Oregon, a non-profit organization that provides individual access to the resources and tools required for the creation of self-published media and art. The IPRC offers workshops, digital technology for writing and design, a research library, and even a letterpress print shop and bindery to aid in the publication of original work.

We think Virginia—and anyone else who loves making an impression—would be proud.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Paper Chase: No. 13 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 129

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Virginia Woolf (1882 – 1941), born Adeline Virginia Stephen, grew up with a steady stream of notable authors visiting her London home. While Virginia and her sister Vanessa had unlimited access to their father’s extensive library, their brothers were sent to Cambridge. This inequality and other Victorian double standards figured prominently in Virginia’s writing. In 1915, she married Leonard Woolf and moved to Hogarth House. There they established the Hogarth Press, publishing the work of T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Vita Sackville-West, the first translations of Sigmund Freud as well as Virginia’s own novels. As editor, typesetter and binder, Virginia had the freedom to control not just the content but the physicality of letterforms and space on a page, declaring herself “the only woman in England free to write what I like.” With Leonard as printer and Vanessa a frequent illustrator, the Hogarth Press published more than 500 books, many far too experimental to be considered by mainstream publishers.

Virginia’s life-long struggle with depression began with a breakdown at age 13 following her mother’s death, and ended after multiple attempts at suicide when she walked into a river with pocketfuls of stones.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, with roots firmly planted in ink-and-paper soil, and souls bound to bloom.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

May 30th, 2011

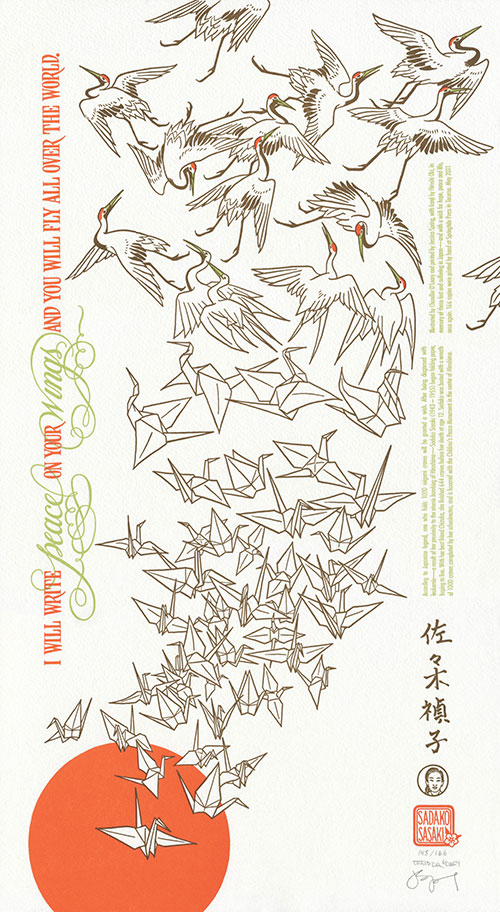

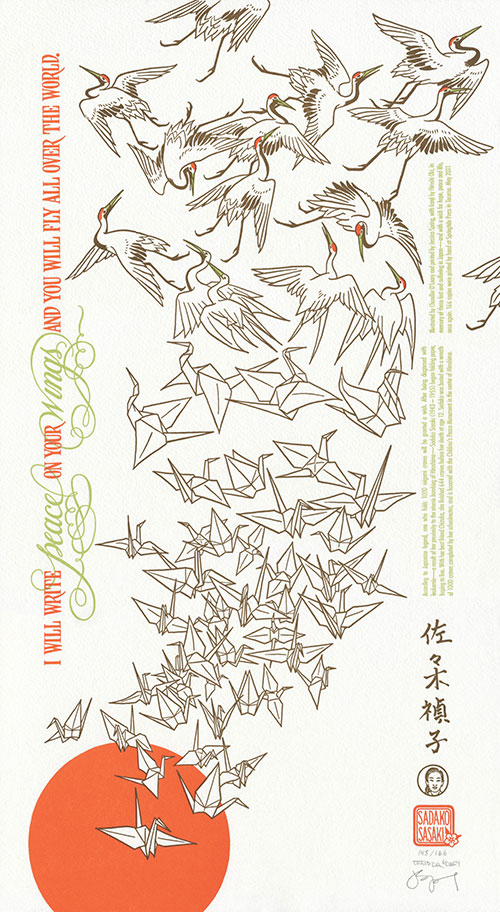

Today is Memorial Day in the United States, a holiday designated for the remembrance of those lost in time of war. But on this day, Jessica and I can’t help but extend our thoughts to others as well, in the spirit of peace. Today our eyes and hearts are trained on the far shores of the Pacific, where the people of Japan are still reeling from the March 11 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. So for our twelfth Dead Feminist broadside, we remember them by giving wings to the words of our youngest-ever feminist:

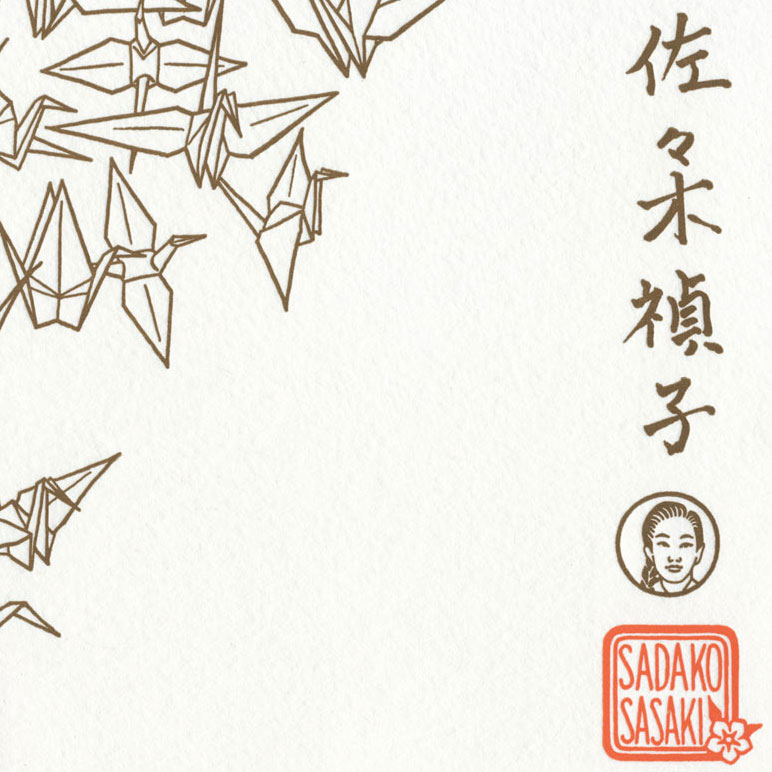

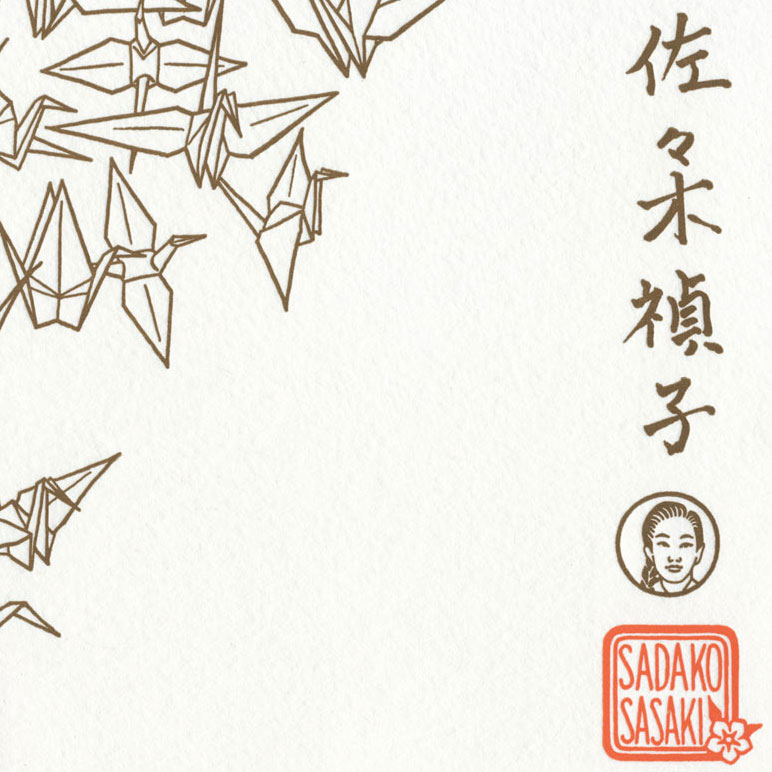

I will write peace on your wings and you will fly all over the world. — Sadako Sasaki

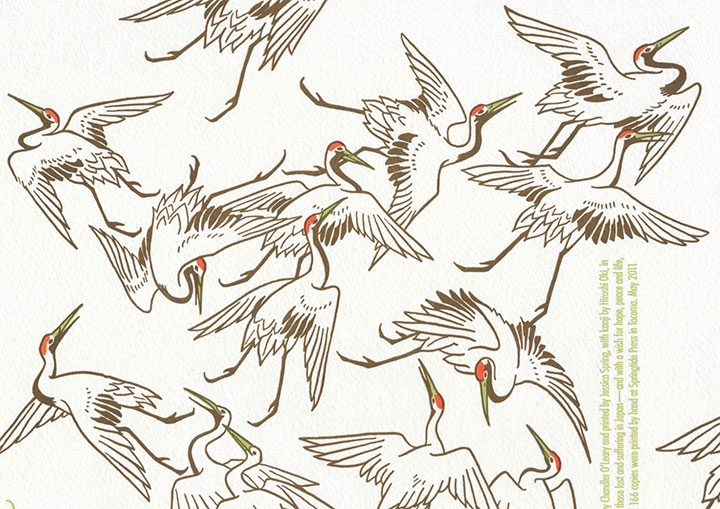

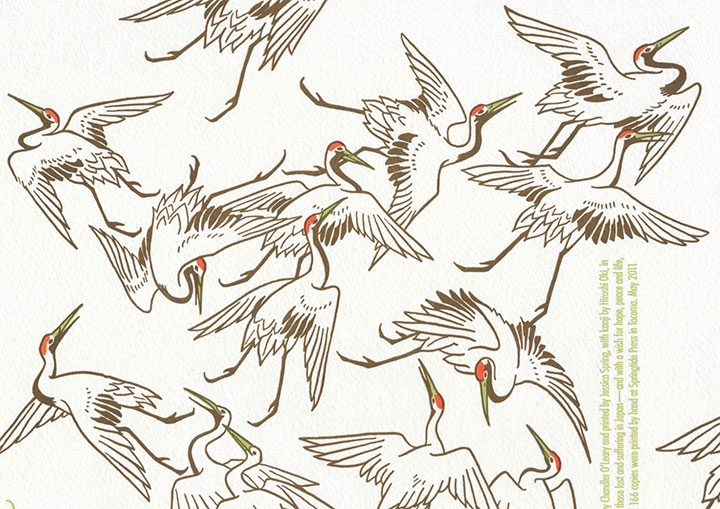

As you can probably tell, this piece is a bit of a departure from our usual way of doing things. This time it just didn’t feel right to let the typography run amok, or to fill every inch of real estate with illustrated goodies. So instead, we simply opened the door and let our imaginations take flight. The quote stands quietly apart, running parallel to a flock of origami cranes rising upward from a persimmon sun. As they follow Sadako’s words and wishes, they transform into red-crowned tancho cranes, disappearing off the page.

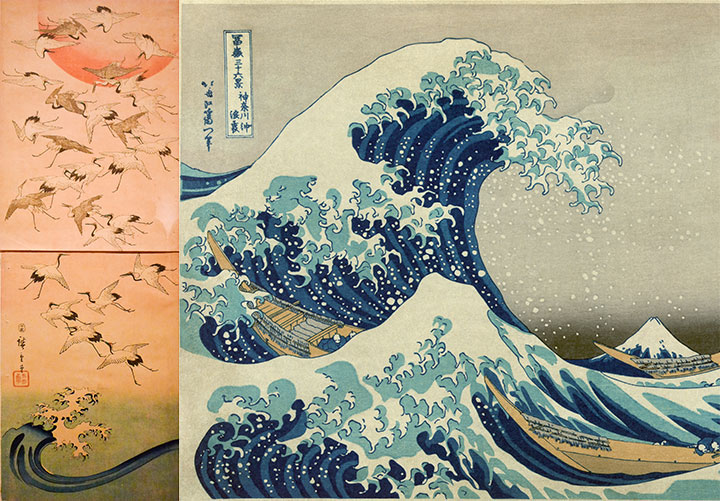

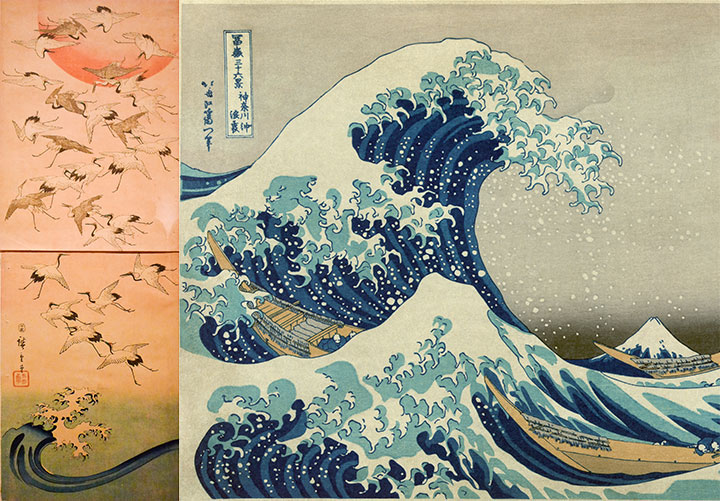

Since the traditions and history of Japanese printmaking are a veritable goldmine, the sky was literally the limit when it came to inspiration. But I had something particular in mind:

On the left is is Cranes and New Year Sun by Utagawa Hiroshige; on the right is Katsushika Hokusai’s famous Great Wave Off Kanagawa. You can see a reference to Great Wave at the bottom of Cranes—making references to both other artists and one’s own older work is a common convention in Japanese art.

I had the good fortune of seeing Cranes and New Year Sun in person earlier this year at the Tacoma Art Museum. Not only is it a beautiful image, it has an interesting quirk that sort of stuck in my craw. See that line running halfway through the composition on the left? The piece is made up of two sheets of paper; it was originally designed to function as the front and rear endsheets of a book. As far as I know, the original viewer never would have seen the image as a whole—and maybe never would have given it a second thought. But together, the two halves of the image form a stunning vertical composition that I wanted to reference for our piece.

There’s also a bit of a practical homage for us here: just as Hiroshige’s illustration is made up of two parts, each one of our Dead Feminist broadsides is also comprised of two halves. For us it’s purely a technical limitation—Jessica’s platemaker can only make plates that are about 8 x 10 inches in size. So since each of our prints is 10 x 18 inches, we have to break the illustration up and print it in two sections: one set of plates for the top, and another for the bottom. So that means that somewhere in every one of our broadsides, there’s a little break running horizontally through the composition. We usually try to hide it as cleverly as possible, or at least blend it in with the overall design, but it’s always there. Take a look at some of our previous prints and see if you can find it. (Mind the gap!)

Anyway, Hiroshige is not the only person we have to thank for all of this. I’d also like to send out a special, winged bit of gratitude to Hiroshi Oki for providing us with his exquisite kanji (Japanese calligraphy) rendition of Sadako’s name—and to his daughter Shiori for introducing us.

The thing that has just enchanted us both about this project is the very idea of imbuing paper with a wish—of creating something so labor-intensive and time consuming, and then sending it out into the world for a greater purpose. Sadako wasn’t the only person to fold cranes for a wish, but she might be the most well-known. Every year, on the anniversary of the atomic bombing, Sadako’s monument in Hiroshima is festooned with thousands upon thousands of cranes—so many that permanent shelters have been erected there to house and protect them. And even in Western countries, it’s become somewhat of a tradition to give senbazuru (a set of 1000 paper cranes) as a gift to cancer patients. Talk about a ripple becoming a tidal wave.

In that spirit, we’ll be donating a portion of our proceeds to Peace Winds America, a non-profit organization based in Seattle and dedicated to disaster response worldwide. The donation will be directed to the Japan Relief & Recovery Fund, used to rebuild local infrastructure and restore the livelihoods and communities of those affected by the earthquake and tsunami. We’d like to think of this as a little senbazuru of our own.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Peace Unfolds: No. 12 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 166

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

According to Japanese legend, one who folds 1000 origami cranes will be granted a wish. After being diagnosed with leukemia—a result of her proximity to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—Sadako Sasaki (1943 – 1955) began folding paper, hoping to live. With her best friend Chizuko, she finished 644 cranes before her death at age 12. Sadako was buried with a wreath of 1000 cranes completed by her schoolmates, and is honored with the Children’s Peace Monument in the center of Hiroshima.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, with kanji by Hiroshi Oki, in memory of those lost and suffering in Japan—and with a wish for hope, peace and life, once again.

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

February 18th, 2011

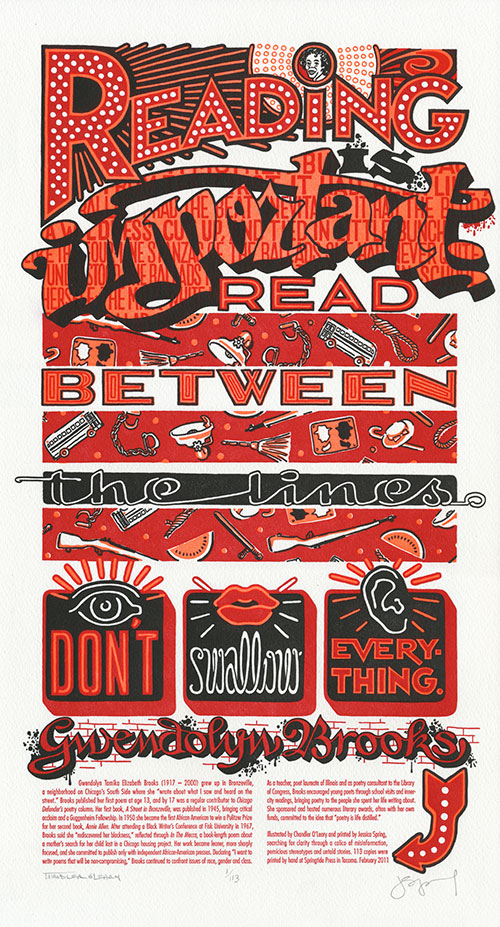

In honor of Black History Month, and of the might of the written word, our newest Dead Feminist is powerhouse poet Gwendolyn Brooks. Without further ado, I’ll hand over my pen to her:

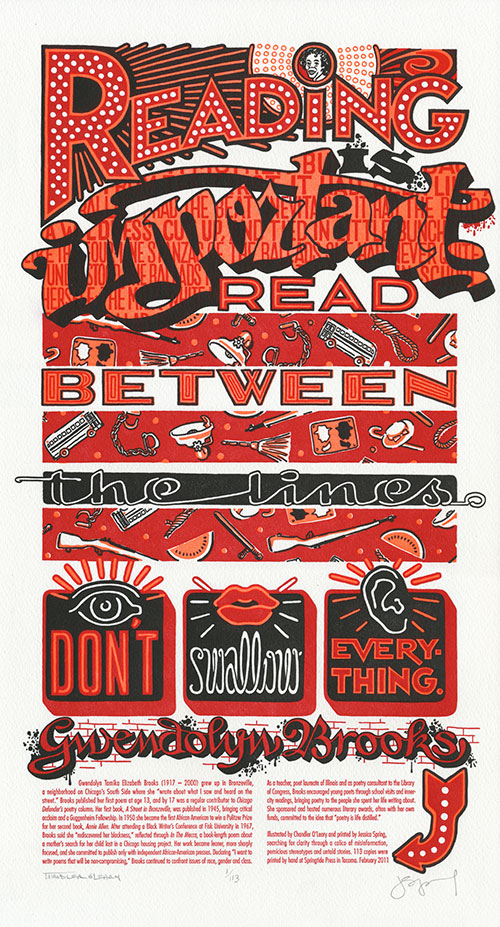

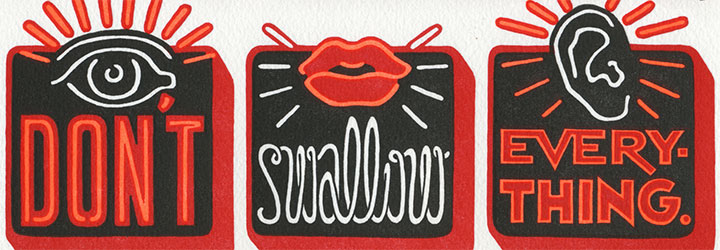

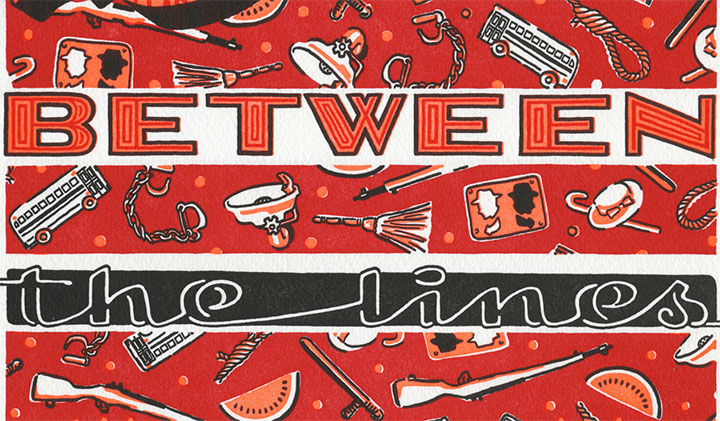

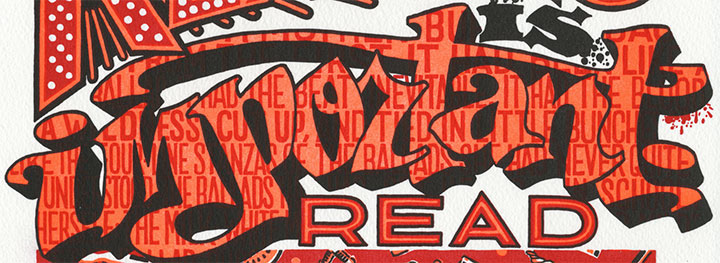

Reading is important. Read between the lines. Don’t swallow everything.

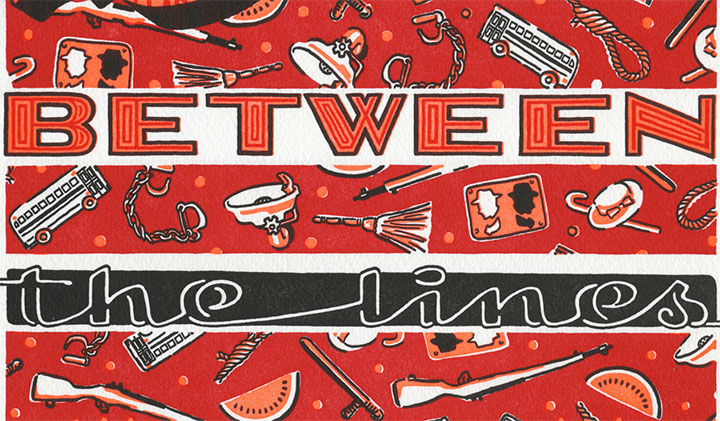

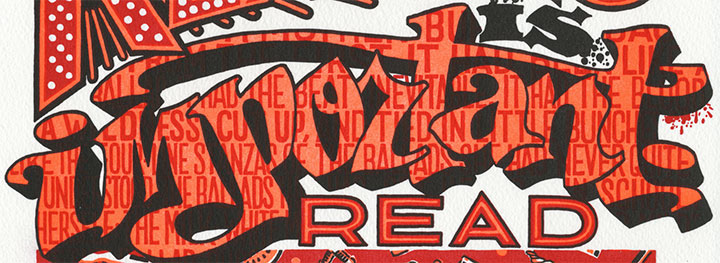

I guess we’re done with the knitting needles and home canning for now; time to don the boxing gloves. This was a tough one, and we almost didn’t have the gall to go through with it. But Gwendolyn Brooks was never one to pull a punch; she faced and shed light on the most uncomfortable truths with bravery and eloquence. And there seem to be an awful lot of uncomfortable truths floating around lately; like a certain congressperson’s assertion that our nation’s founding fathers ended slavery, or the fact that no matter how many African American Presidents we elect, racism isn’t dead. (Don’t believe me? Even my most cursory historical research brought up all sorts of fresh, modern hatred. Try it for yourself and do an online image search for “watermelon stereotype”—if you can stomach it. Just keep an airsick bag handy, because it ain’t pretty.)

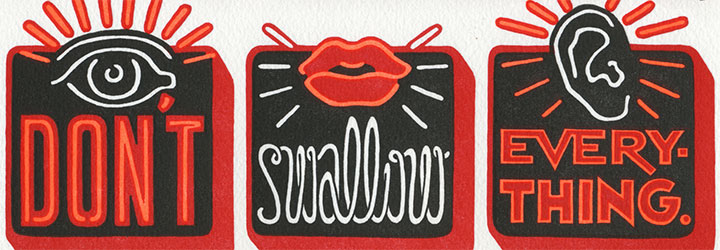

So in tribute to Brooks’s courage, Warning Signs is a riot of color and fluorescent ink, glowing like an urban beacon. Flashing neon and spattered graffiti confront us, sounding the alarm with every word. Beneath the fluorescent current runs a blood-red repeating calico pattern of violence and cruelty—a tapestry that forms the unfortunate warp to the weft of our past and present.

And as an undercurrent to the undercurrent, behind the graffiti reads the first stanza of Brooks’s poem, “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon.” The poem grapples with the brutal 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till, and weaves a tale of remorse and confusion from the perspective of Carolyn Bryant, the white woman whose accusations that Till flirted with her provoked her husband to abduct and kill the boy. But we didn’t choose the poem for its subject matter, per se—we chose it for the articulate beauty with which Brooks tells the story. It’s still a punch to the gut, but when she knocks you flat you see some awfully pretty stars.

A portion of the proceeds from Warning Signs will be donated to 826CHI, a non-profit Chicago writing and tutoring center. 826CHI is dedicated to supporting the writing skills of students ages 6 to 18, and to helping teachers inspire their students to write—their mission is to “strengthen each student’s power to express ideas effectively, creatively, confidently, and in his or her individual voice.” We think Ms. Brooks would approve.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Warning Signs: No. 11 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 113

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Gwendolyn Tamika Elizabeth Brooks (1917 – 2000) grew up in Bronzeville, a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side where she “wrote about what I saw and heard on the street.” Brooks published her first poem at age 13, and by 17 was a regular contributor to Chicago Defender’s poetry column. Her first book, A Street in Bronzeville, was published in 1945, bringing critical acclaim and a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1950 she became the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for her second book, Annie Allen. After attending a Black Writer’s Conference at Fisk University in 1967, Brooks said she “rediscovered her blackness,” reflected through In The Mecca, a book-length poem about a mother’s search for her child lost in a Chicago housing project. Her work became leaner, more sharply focused, and she committed to publish only with independent African-American presses. Declaring “I want to write poems that will be non-compromising,” Brooks continued to confront issues of race, gender and class.

As a teacher, poet laureate of Illinois and as poetry consultant to the Library of Congress, Brooks encouraged young poets through school visits and inner-city readings, bringing poetry to the people she spent her life writing about. She sponsored and hosted numerous literary awards, often with her own funds, committed to the idea that “poetry is life distilled.”

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

November 10th, 2010

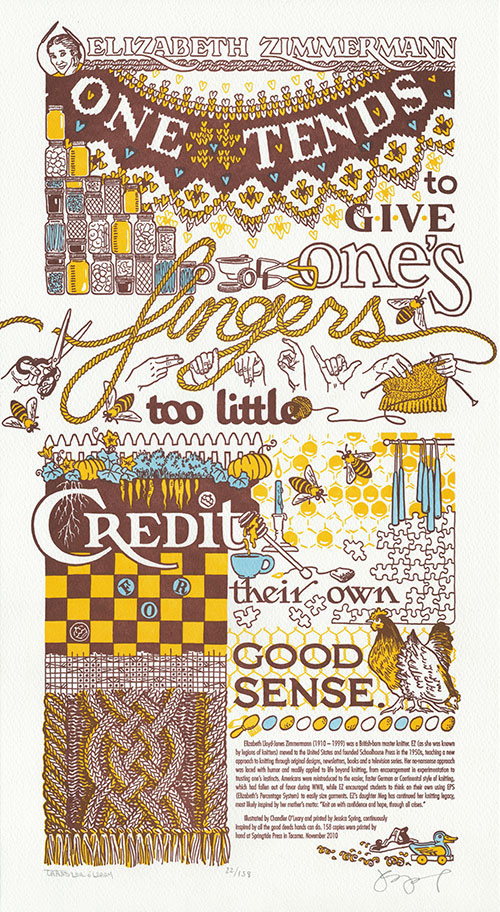

Maybe it’s the changing seasons. Or the fact that the farmers market runneth over with delicious autumn goodies. Or maybe we just wanted to talk about something that made us smile, for a change—because this time, for our tenth Dead Feminist broadside, Jessica and I have turned to a subject somewhat lighter of heart.

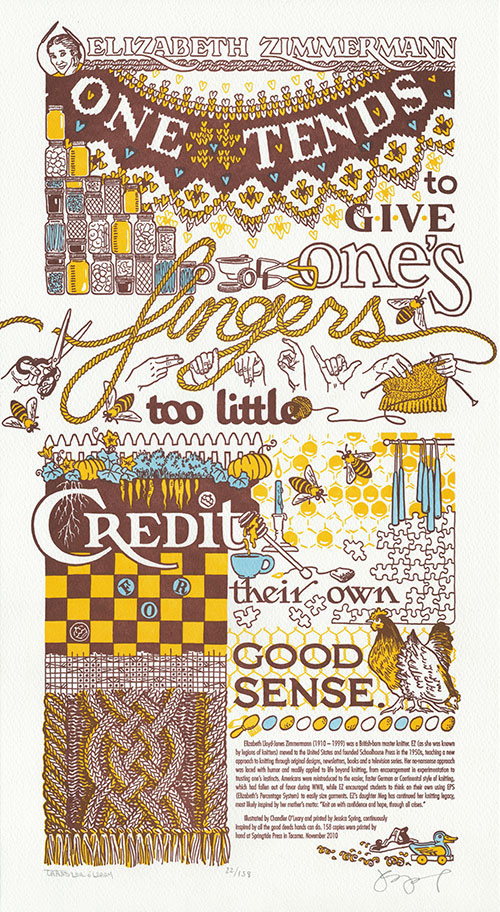

From the likes of urban homesteaders, artisans, D.I.Y.-ers, and hobbyists of all stripes, brilliant handiwork is all around us. We are in constant admiration of the power of one’s own two hands, and the good deeds they can do. And for the perfect symbol of a handmade life infused with joy and meaning, we’ve handed the microphone to Elizabeth Zimmermann:

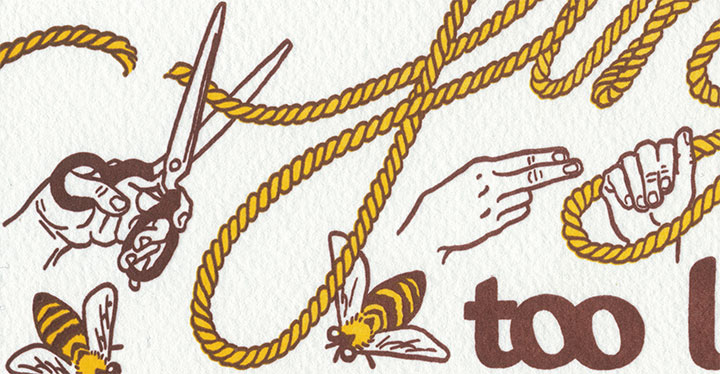

One tends to give one’s fingers too little credit for their own good sense.

Now, as many of you probably know, Ms. Zimmermann was a knitter (that’s an understatement; I’d say more like All-Time Super-Queen Knitter of the Cosmos, Forever and Ever, Amen). But like every knitter, there is so, so much more to her than that. So rather than simply leaving it at yarn and wool, we discovered a cornucopia of the pursuits that fingers like to turn to when they’re not knitting. There are no idle hands here, to be sure.

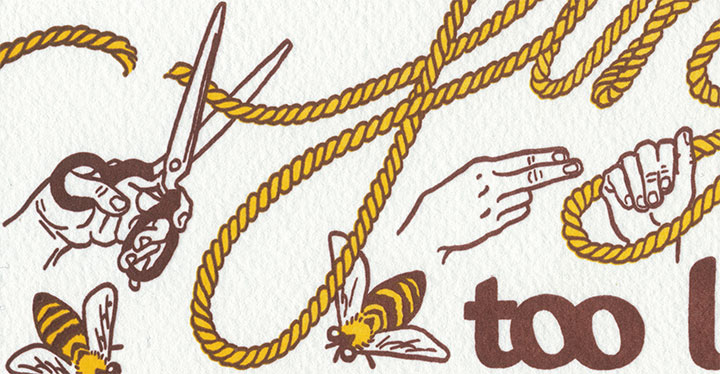

Just in time for the fall harvest and in cozy preparation for the winter months ahead (or for our friends in the southern hemisphere, looking forward to a fruitful summer), Get Handy overflows with simple pleasures and home comforts. Elizabeth drafts a cable pattern and whips up a Fair Isle yoke. A little slow food takes root in the garden. Honeybees guard a new crop of candles. Fresh home-canned treats stock the shelves. Chickens scratch along a fence of golden (darning) eggs. Over a cup of tea, puzzles piece together and checkers crown kings. And when they’ve put down the yarn and scissors, the hands spell it out for you in American Sign Language.

Oh, and the Tailor’s blueberries and Jessica’s dilly beans make a cameo appearance. Yum.

A portion of the proceeds from Get Handy will be donated to the amazing healing hands of Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders, via Tricoteuses Sans Frontières / Knitters Without Borders, which organizes knitters to raise funds for MSF/DWB. MSF, winner of the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, is a medical relief organization dedicated to assisting people in distress around the world.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Get Handy: No. 10 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 158

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is hand-colored and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Elizabeth Lloyd-Jones Zimmermann (1910 – 1999) was a British-born master knitter. EZ (as she was known by legions of knitters) moved to the United States and founded Schoolhouse Press in the 1950s, teaching a new approach to knitting through original designs, newsletters, books and a television series. Her no-nonsense approach was laced with humor and readily applied to life beyond knitting, from encouragement in experimentation to trusting one’s own instincts. Americans were reintroduced to the easier, faster German or Continental style of knitting, which had fallen out of favor during WWII, while EZ encouraged students to think on their own using EPS (Elizabeth’s Percentage System) to easily size garments. EZ’s daughter Meg had continued her knitting legacy, most likely inspired by her mother’s motto: “Knit on with confidence and hope, through all crises.”

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

September 3rd, 2010

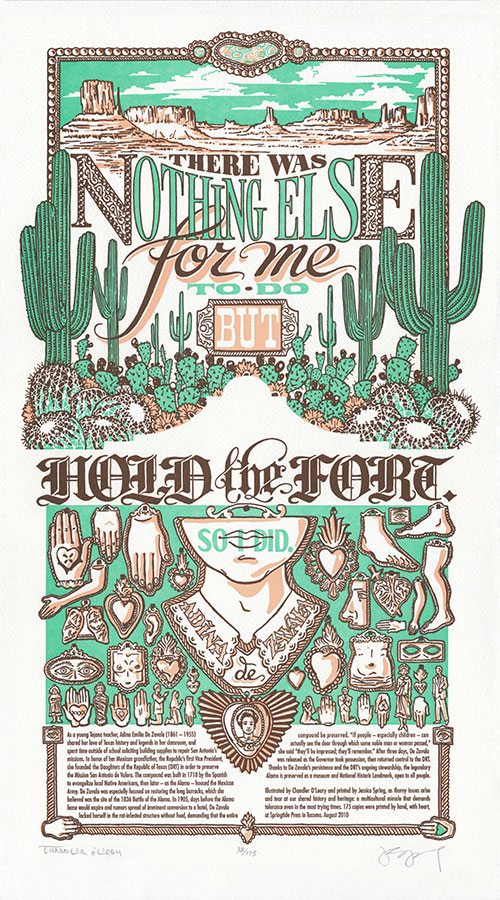

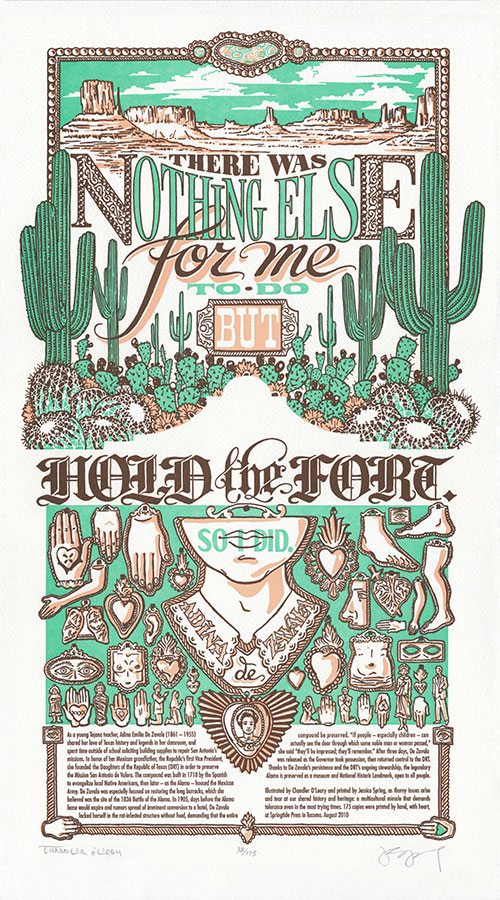

As autumn approaches and the inevitable rainy season knocks at our doors, Jessica and I are dreaming of the sunny skies of Arizona—where the not-so-sunny SB 1070, the state’s contentious new immigration reform bill, was signed into law earlier this year. At every turn, controversy pricks underfoot and looms overhead—with no easy, clear-cut answers in sight. So for our newest Dead Feminist broadside, we decided to challenge the controversy face-to-face-to-hand-to-heart with the words of Tejana activist Adina De Zavala:

There was nothing else for me to do but hold the fort. So I did.

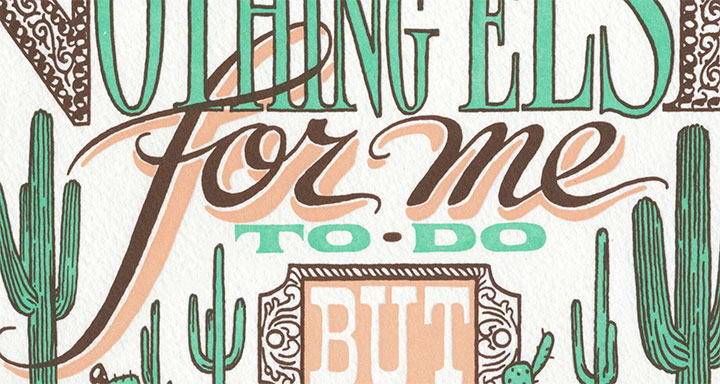

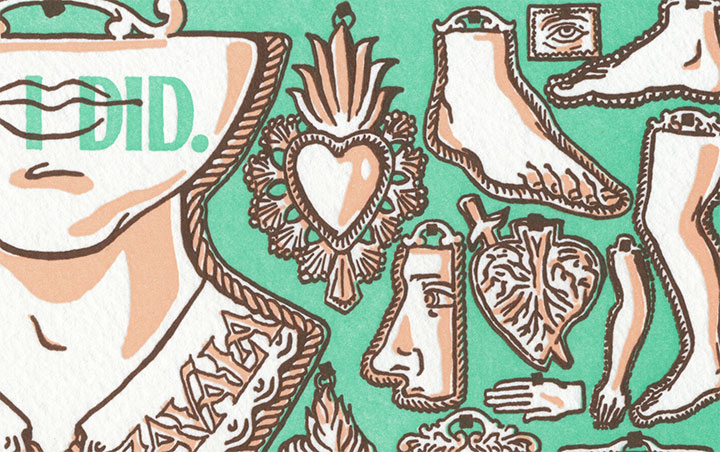

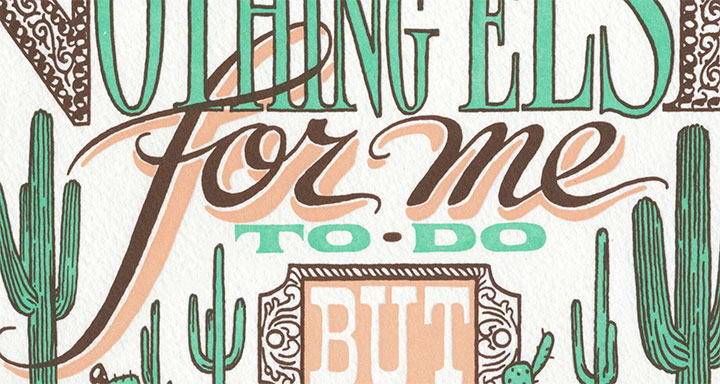

In complete contrast with our last broadside, we had a short n’ sweet quote to work with this time—which gave me every reason and all kinds of room to go completely nuts with the imagery. I think my subconscious had a hand in steering us toward Adina and her quote, because I suddenly had the chance to explore a whole slew of filed-away themes and images that I had never been able to work into a piece before. My brain was swimming with ideas, and I found myself cackling out loud at the prospect of finally getting the chance to put so many of my favorite things into one crazy illustration. Green skies! Monument Valley! Mexican blackletter! Milagros! Cactus-spine fractal geometry! Mwa ha ha!

Ahem. I should probably back up the train a bit and give you the whole nerdy spiel.

On a Mission teems with icons of both the American Southwest and Mexican folk culture. A desert landscape—framed with metallic scrollwork and crazy-lace agate cabochons— stretches to the horizon, while saguaro sentinels tower over a tangled mess of prickly pears and barrel cacti. That was the easy part—thorny issue? Check.

The hard part was putting in all of our nebulous and conflicted feelings about the Alamo (represented here as an absence of imagery; a silhouette of negative space) and the topic at hand. So for answers I looked to Mexican folk art—so prominent on both sides of the Border, and so beautifully expressive, layered in history and meaning.

The text itself helped us get right to the point about that. The typography is influenced both by the American Old West and modern-day Mexico—particularly the latter. Mexico’s strong tradition of hand-lettering survives today, particularly in the form of hand-painted signs and advertisements. Inspiration ranged from the fluid folksiness of drop-shadowed cursive script—

—to the proud refinement of blackletter, a hold-out of the early Spanish colonial printers that has evolved to attain near-sacred importance in Mexican and Mexican-American popular culture. As we were conscious of our desire to “reclaim” some of the connotations behind the Alamo, blackletter provided the perfect weight and cultural twist to the phrase “Hold the fort.”

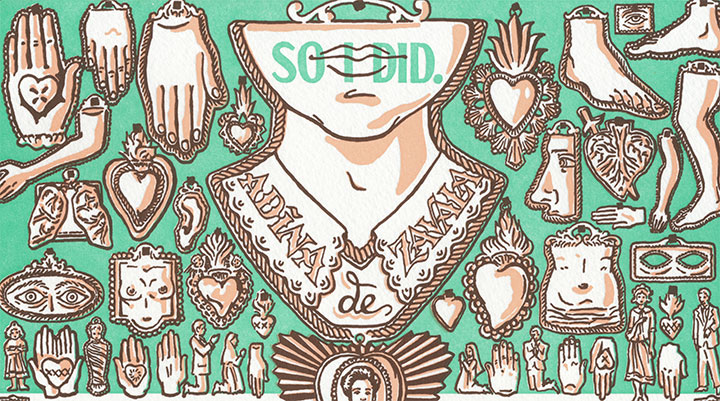

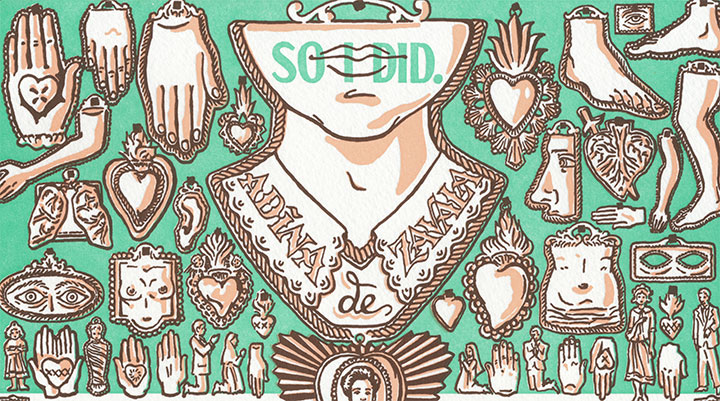

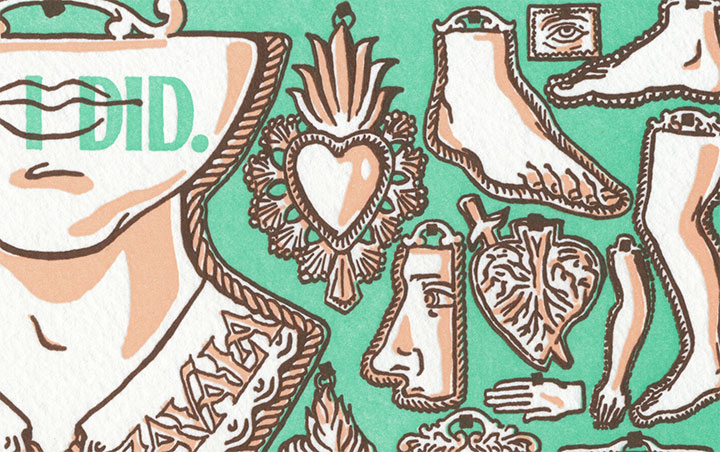

And then there’s my favorite part of the whole project: strewn all over the lower half of the illustration is a collection of milagros. Literally translated to “miracles,” milagros are small, stamped-metal votives that are typically hung in the shrines and churches of many Catholic countries—offered up in thanks for prayers answered and blessings received.

On my lifetime list of All-around Best Things Ever, milagros are very near the top—as evidenced by the growing collection in my studio. When I lived in Rome (where they are called ex votos), I used to pick them up on Sunday-mornings at the Porta Portese flea market for next to nothing. Ever since then, they’ve popped up in my work every now and then.

Well, now they get to be the stars of the show. If the Alamo were still the mission I picture in my head, the walls would be covered, floor to ceiling, with milagros. And since Adina herself has become a bit of a legend for her place in the Alamo’s history, illustrated devotionals adorn her name and portrait like pinned hopes.

It may seem strange to get so giddily excited about illustrating such a serious topic, but somewhere along the way I realized that it’s that excitement over the positive that has given me perspective on the issue at hand. That what we think of as the “American” Southwest is so iconic and so dear to us because of the peoples with whom we share it. That the Southwest wouldn’t be what it is without its link to hundreds of years of both native and newcomer culture—just as America wouldn’t be America without immigration and cultural diversity. That keeping our multicultural vibrance alive is what makes us whole.

So in that spirit, a portion of the proceeds from On a Mission will be donated to the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project, a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting justice and legal rights for immigrants and refugees from more than 100 countries around the world.

I don’t know if any of this stuff crossed Adina De Zavala’s mind while she camped out inside the Alamo. She was just an individual who fought to keep an old, rotting building standing—and the place was a controversial symbol, even then (it certainly still is today). But she knew that the controversy was part of the legend of the place, and part of our heritage. And she knew the value of preserving that heritage for everyone’s benefit, without exception—so she held the fort. I think she deserves a few milagros on our wall for that.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

On a Mission: No. 9 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 175

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

As a young Tejana teacher, Adina Emilia De Zavala (1861 – 1955) shared her love of Texas history and legends in her classroom, and spent time outside of school soliciting building supplies to repair San Antonio’s missions. In honor of her Mexican grandfather, the Republic’s first Vice President, she founded the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) in order to preserve the Mission San Antonio de Valero. The compound was built in 1718 by the Spanish to evangelize local Native Americans, then later—as the Alamo—housed the Mexican Army. De Zavala was especially focused on restoring the long barracks, which she believed was the site of the 1836 Battle of the Alamo. In 1905, days before the Alamo lease would expire and rumors spread of imminent conversion to a hotel, De Zavala locked herself in the rat-infested structure without food, demanding that the entire compound be preserved. “If people—especially children—can actually see the door through which some noble man or woman passed,” she said, “they’ll be impressed; they’ll remember.” After three days, De Zavala was released as the Governor took possession, then returned control to the DRT. Thanks to De Zavala’s persistence and the DRT’s ongoing stewardship, the legendary Alamo is preserved as a museum and National Historic Landmark, open to all people.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, as thorny issues arise and tear at our shared history and heritage: a multicultural miracle that demands tolerance even in the most trying times. 175 copies were printed by hand, with heart, at Springtide Press in Tacoma. August 2010

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

June 9th, 2010

Okay, I know the title is a bit controversial. But it was either that or something laden with obscenities—Jessica and I are feeling murderous less than charitable towards the oil industry at the moment. Thus far the Deepwater Horizon/British Petroleum oil “spill” (leak? deluge? hemorrhage?) has poured tens of millions of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico—a fact that stopped us in our tracks, mid-way through a different piece, and changed our course for this season’s broadside.

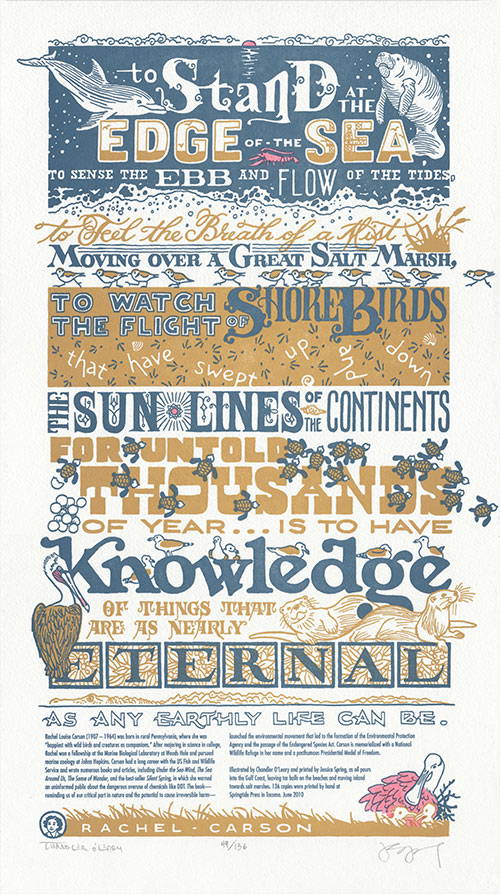

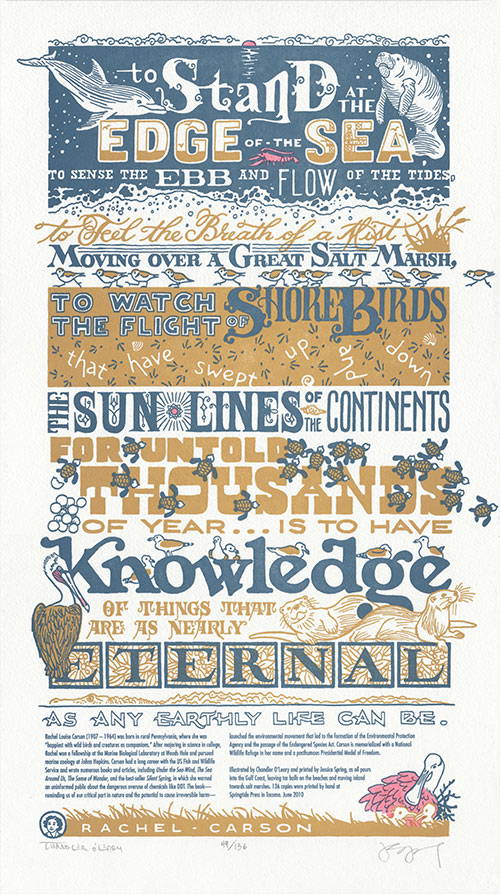

I wish I could say this was a fun piece to create; dwelling on current events and spending days poring through images of oil-soaked animals has been one of the most depressing, enraging experiences I’ve had in my career. Luckily, I could spend the rest of my energy drawing the inspiring quote by writer, scientist and environmentalist Rachel Carson:

“To stand at the edge of the sea, to sense the ebb and flow of the tides, to feel the breath of a mist moving over a great salt marsh, to watch the flight of shore birds that have swept up and down the sun lines of the continents for untold thousands of year* … is to have knowledge of things that are as nearly eternal as any earthly life can be.”

(*not a typo, I promise.)

This is by far the longest quote we’ve tackled yet, and I needed convincing before I could justify the pins and needles I’d feel in my hand afterward. But along the way, it occurred to me that the quote reads like a poem—with a rhythm that opened up all kinds of image possibilities.

I couldn’t face the idea of drawing any of the oil spill’s destruction, so I chose instead to focus on the wildlife affected by the spill—including several already-endangered species—and create an image absolutely teeming with life. A manatee and dolphin play in deep ocean blue, while plovers dash by in a sandy gold that becomes the sickly tea-colored oil pouring from a hidden offshore rig (okay, so maybe a little of my anger found its way into the drawing). Baby sea turtles inch their way to the shore; a roseate spoonbill nests in a corner; a brown pelican sits, surveying the scene. How many creatures can you find?

One positive note that we can hold onto is the hope that we might make a bit of difference with our art. Our Dead Feminists have made their way to 40 states and 9 countries outside the U.S., so the word is definitely spreading. And we’ll be donating a portion of the proceeds from Drill, Baby, Drill to Oceana, an international organization focused on ocean conservation and dedicated to ending offshore drilling.

There. I said it. We want to ban offshore drilling outright. Forever.

I don’t mean to offend any readers on the other side of that particular fence (if any are left; sometimes I wonder if our series hasn’t already alienated half of the population…), but this is one issue around which I simply cannot tiptoe.

But then again, Rachel Carson wouldn’t have, either.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Drill, Baby, Drill: No. 8 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 136

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag paper. Each piece is hand-colored and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Rachel Louise Carson (1907 – 1964) was born in rural Pennsylvania, where she was “happiest with wild birds and creatures as companions.” After majoring in science in college, Rachel won a fellowship at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole and pursued marine zoology at Johns Hopkins. Carson had a long career with the US Fish and Wildlife Service and wrote numerous books and articles, including Under the Sea-Wind, The Sea Around Us, The Sense of Wonder, and the best-seller Silent Spring, in which she warned an uninformed public about the dangerous overuse of chemicals like DDT. The book—reminding us of our critical part in nature and the potential to cause irreversible harm—launched the environmental movement that led to the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of the Endangered Species Act. Carson is memorialized with a National Wildlife Refuge in her name and a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, as oil pours into the Gulf Coast, leaving tar balls on the beaches and moving inland towards salt marshes. 136 copies were printed by hand at Springtide Press in Tacoma. June 2010

UPDATE: poster is sold out. Reproduction postcards available in the Dead Feminists shop!

![Chandler O'Leary [logo]](https://chandleroleary.com/wp-content/themes/chandleroleary/images/logo.png)